In June 1933 Paul Nash sent a letter to The Times announcing the formation of Unit One, an eclectic array of artists that included British modernist titans Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth and Ben Nicholson. The same year exhibitions of Joan Miró and Max Ernst in London caught the attention of the British avant-garde, acting as a catalyst for Britain’s distinctive fusion of the prevalent binary of abstraction and surrealism.

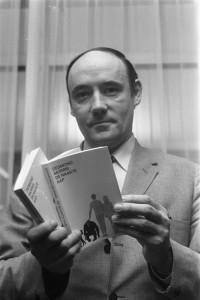

Something was in the air and Tristram Hillier, as an artist in his twenties and a recent graduate of the progressive Slade School of Fine Art, was there to absorb it: within a year he had joined Unit One and exhibited in their landmark (and indeed, only) exhibition at the Mayor Gallery, organised by ICA founder Herbert Read.

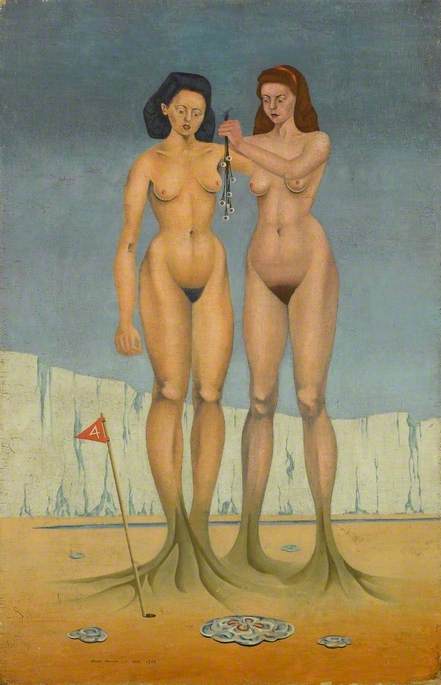

Art historians have a tendency to prioritise continental surrealism, often undervaluing the significant input of British artists to developing the surrealist vernacular. British surrealism was driven by a group of artists of disparate styles that included Eileen Agar, Ithell Colquhoun and Roland Penrose, the latter of whose work as an art historian contributed equally to written accounts of the movement’s origins and proponents.

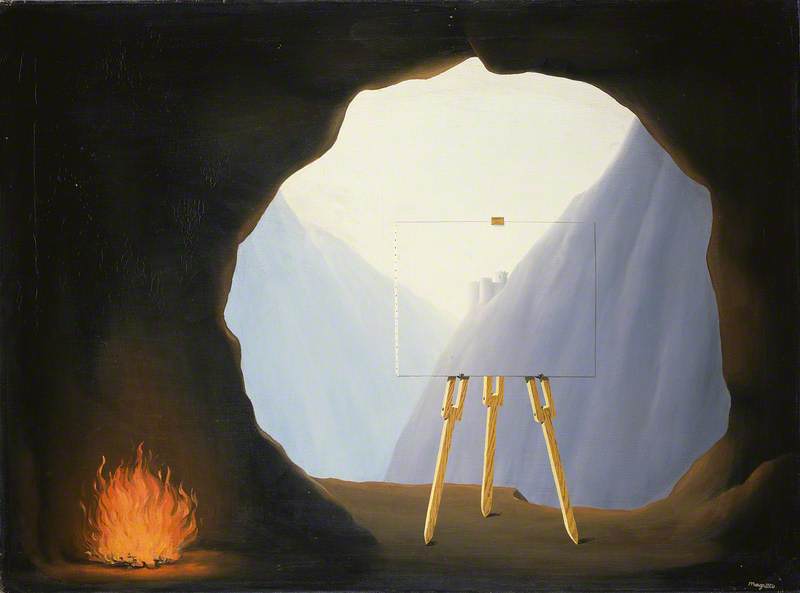

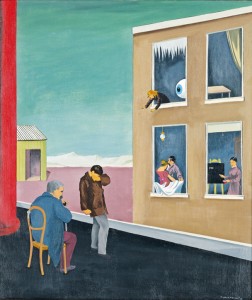

In his paintings, Penrose reconfigured the female nudes of Salvador Dali, the birds of Max Ernst and the optical tricks of Magritte to construct paintings that were increasingly political and urgent. The work of Tristram Hillier, on the other hand, doesn’t fit quite so neatly into the pantheon of high surrealists from whom Penrose took his cues.

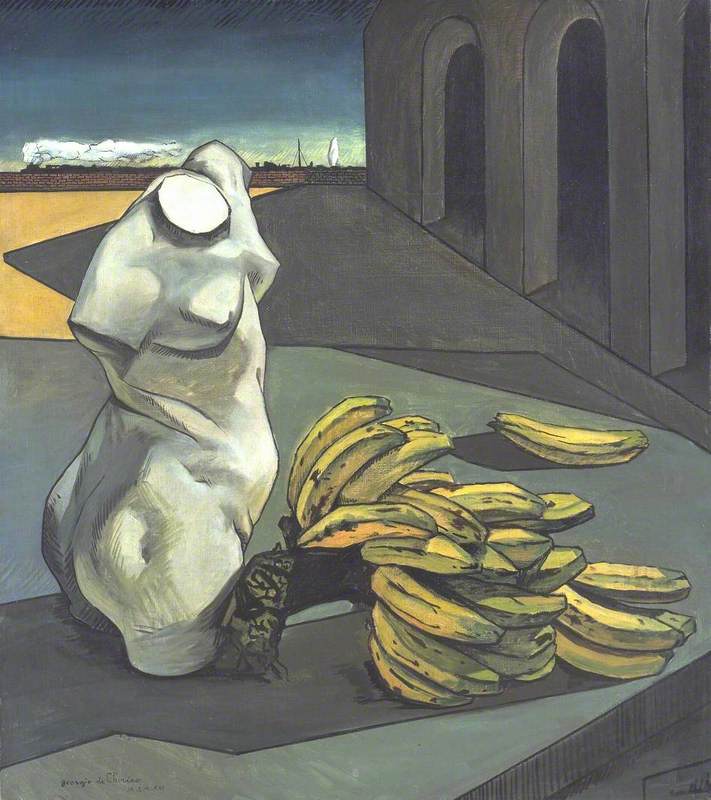

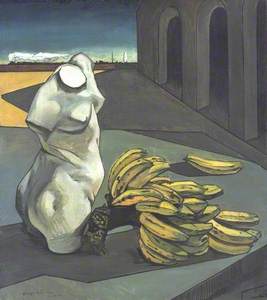

Indeed, Hillier’s paintings have more in common with the proto-surrealism or metaphysical art of Giorgio de Chirico. Profoundly affected by the deserted medieval city of Ferrara, de Chirico’s work can be generally split into two groups. The first are still lifes of visual non-sequiturs, such as a marble Hellenic bust alongside a rubber glove, or a sculptural nude in contrapposto that casts its shadow across a branch of bananas.

The second are eerie cityscapes: deserted piazzas with long arcades that paraphrase classical architecture, shadows of varying lengths that confuse attempts to project a time of day, and sinister silhouettes of military figures on horseback that hint at the impending threat of the First World War.

Une ferme abandonnée en Mayenne

1981

Tristram Paul Hillier (1905–1983)

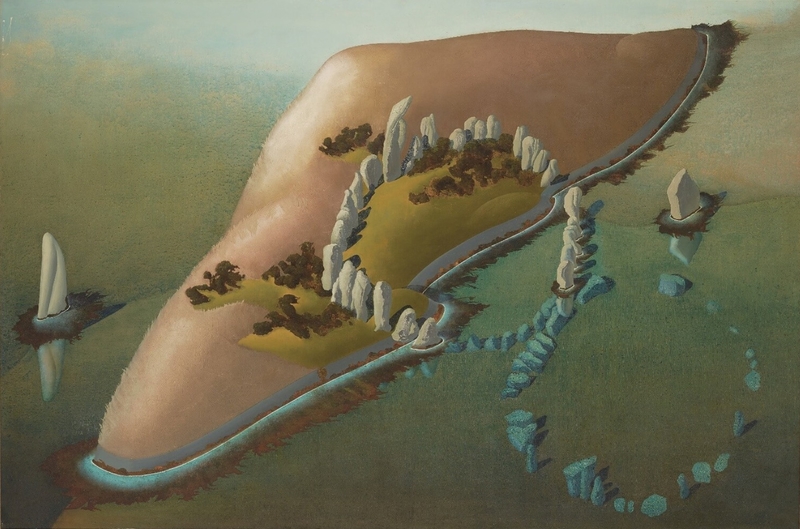

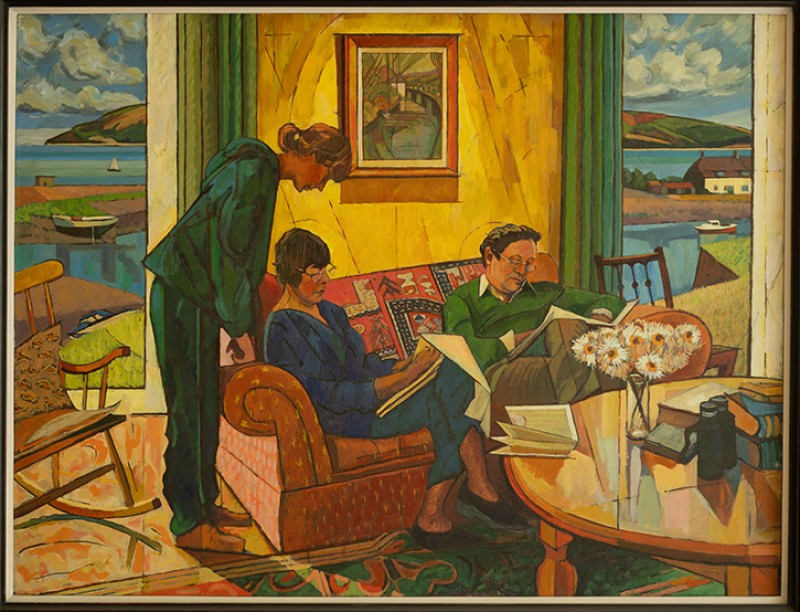

Hillier’s paintings share a similar attention to texture. In the flat, mirror of a river or lake in Une ferme abandonnée en Mayenne (1981), or in an earlier example the Flooded Meadow (1949), surfaces are rendered with pin-sharp precision, opaque and flat as a sheet of ice.

Hillier also had an equal interest in areas of activity that have been absented of human life, lending his towns, harbours, factories and farms an air of futility, perhaps a nod to the increasing disappearance of Britain’s industrial and maritime heritage. However, unlike the theatrically ravaged landscapes of post-war British artists of Paul Nash or Graham Sutherland, Hillier’s landscapes possess an unsettling tranquility – a sense of indeterminable threat bubbling underneath the surface.

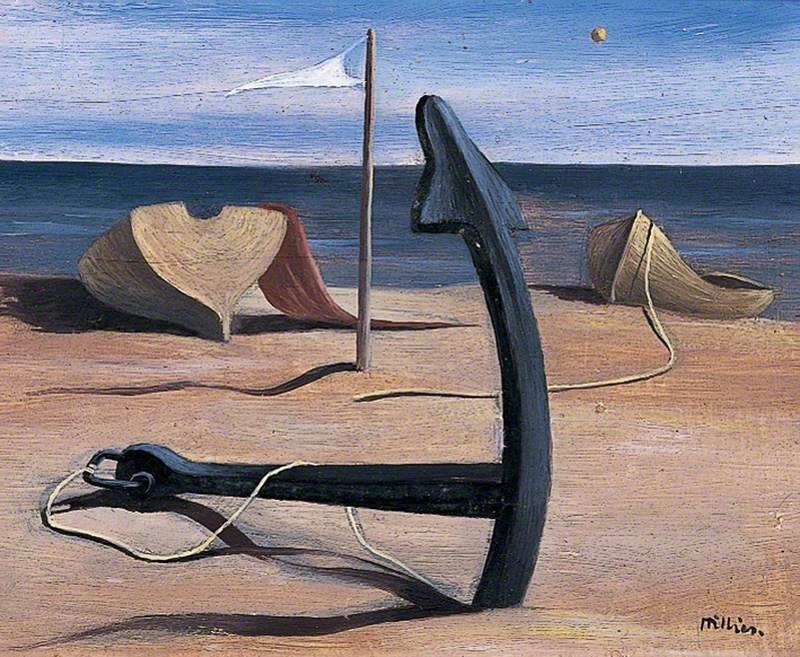

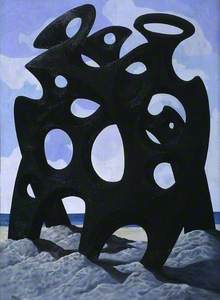

Despite his classification within the Unit One group, it’s also significant that Hillier blurred the line between the dogmatic binary of abstraction and surrealism more deliberately than most, a notable example being his Variation on the Form of an Anchor (1939).

Here we see a novel attempt at formulating an imagined sculpture in paint, in this case a vaguely anthropomorphic cluster of abstracted heads and bodies that loom as silhouettes and block the arcadian promise of the background’s joyous blue sky.

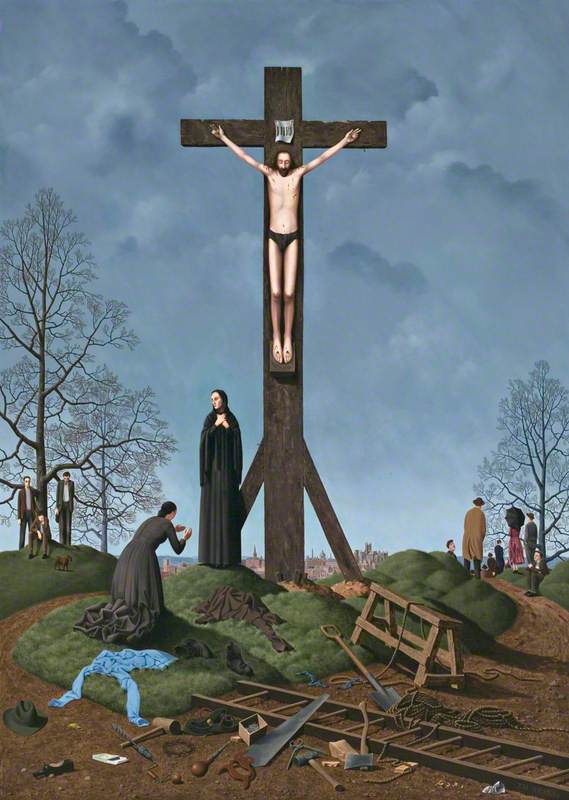

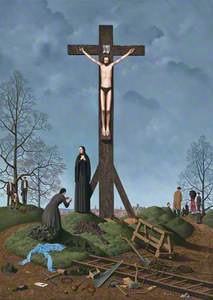

Hillier’s devout Christianity is another crucial factor in attempts to unpick his most cryptic and considered work: the astonishing Crucifixion of 1954, for example, reconciles the rigidity and formalism of a Jan van Eyck or Rogier van der Weyden altarpiece with a distinctly contemporary setting. Here mourners wear tweed suits and carry umbrellas, and like the artists of the Italian Renaissance who used their local landscapes to illustrate biblical stories, in the distance the topography of London emerges. By merging the sacred and the contemporary, Hillier paraphrases the moral messages of the Bible to argue for their continued relevance in a society devastated by war.

Approaching it from this perspective, it becomes clearer why Hillier’s work has been mistakenly regarded as secondary. His modest paintings forego the avant-garde maxim of iconoclasm as progress, of destruction as a means of renewal – instead opting to quietly modulate the tropes of surrealism to a deeply personal and spiritual register. His fear of war, his love of the British landscape and his profound Christianity provide a unique insight into one man’s experience of post-war Britain, and all that was lost with it.

Liam Hess, freelance arts writer based in London