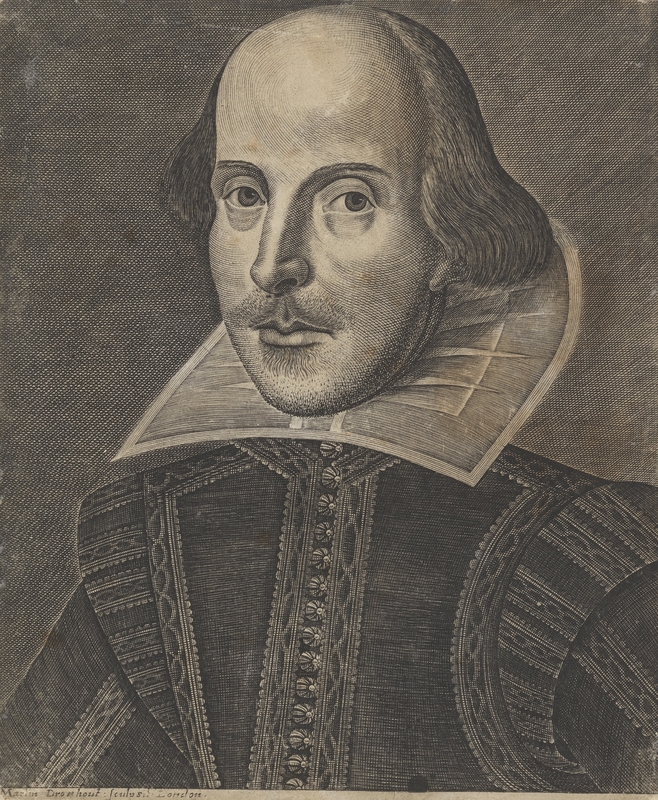

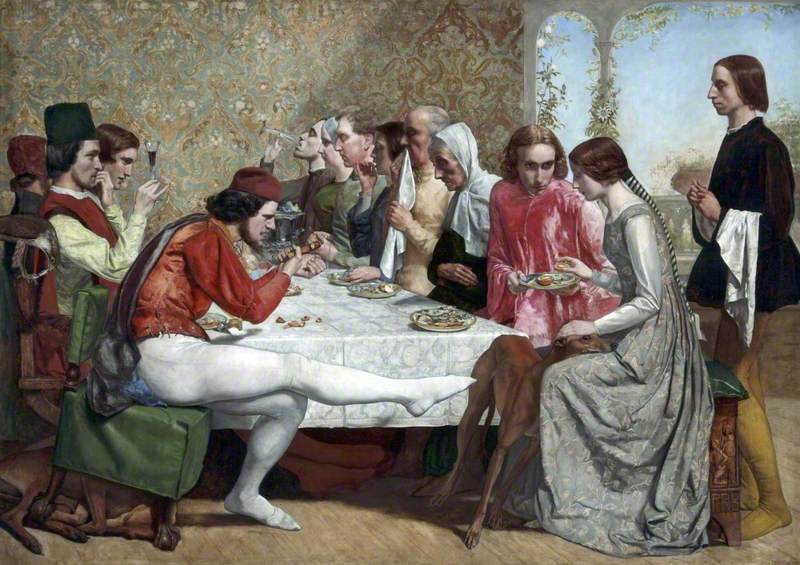

What do you think of when you hear the name 'Ophelia'?

For many, the image of a wide-eyed, distressed young maiden with flowers in her hair probably comes to mind. An ill-fated young Danish noblewoman in Shakespeare's Hamlet, she's often presented weaving garlands, or draped over a willow branch beside a riverbank. The details differ but the scene is the same: Ophelia, within the visual language of popular imagination, is defined by her death.

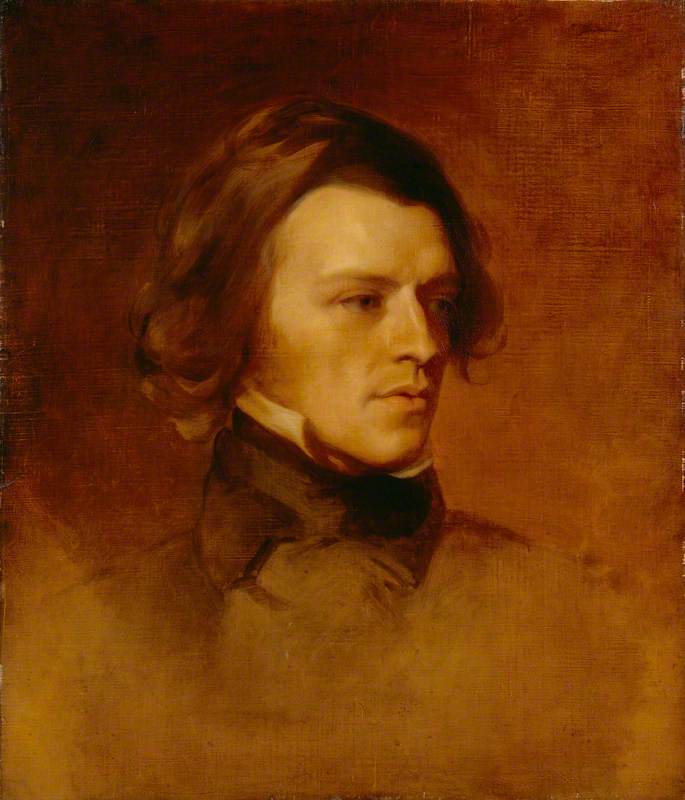

Ophelia

1894, oil on canvas by John William Waterhouse (1849–1917)

Repeatedly, we see one particular version of Ophelia recreated by artists, one which is cemented within the popular imagination and reflected in subsequent pop culture. In some ways, this is unsurprising. Much of the appeal is, of course, the romantic tragedy of the scenario. A young, beautiful noblewoman who comes oh-so-close close to marrying her prince, but madness and obsession on his part lead to his cruel rejection of her, ultimately leading to her drowning after a branch breaks on the willow tree on which she is reclining.

The combination of romantic heartbreak, death and youth is undoubtedly an alluring one. These are themes that can be found again and again within all types of storytelling, as seen in the tale of Shakespeare's star-crossed lovers, Romeo and Juliet.

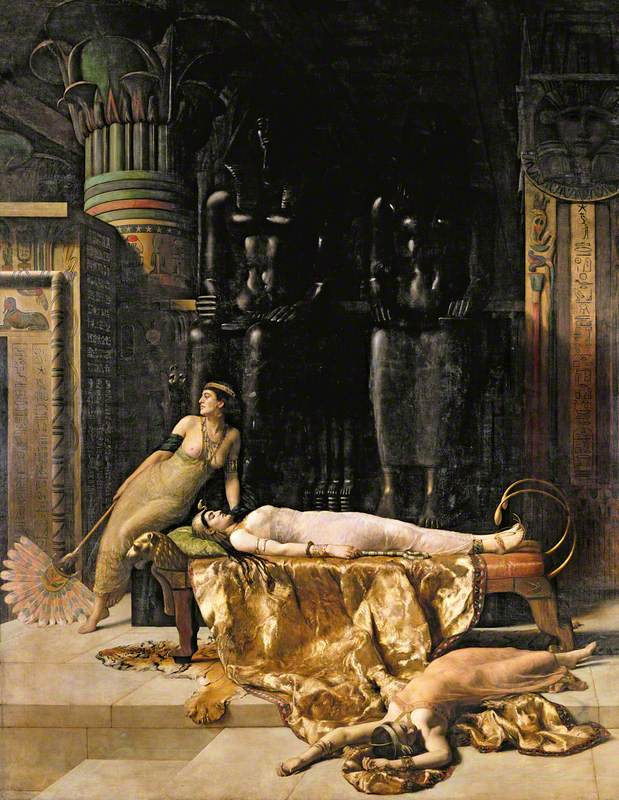

There are reasons why there exist more visual representations of Ophelia on the riverbank than Juliet in the tomb. Much of the pull towards Ophelia no doubt lies in the visuals presented in Queen Gertrude's speech announcing her death: her death takes place off-screen, giving artists greater license to use their imaginations (as seen in Constantin Meunier's rendition below).

Ophelia

1851–1905, oil on canvas by Constantin Meunier (1831–1905)

Gertrude's speech – a particularly beautiful and moving piece of writing – is filled with images of flowers, evoking Ophelia's earlier use of plants and flowers, and what they represent to upbraid the court. Their association with life and beauty also means that they have historically featured prominently in representations of memento mori. It is presumably precisely that contrast – the beauty of the flowers and the maiden to reflect the sadness and ugliness of death – that so enraptures artists. This is not just a tragic death, it is a death that also happens to look beautiful.

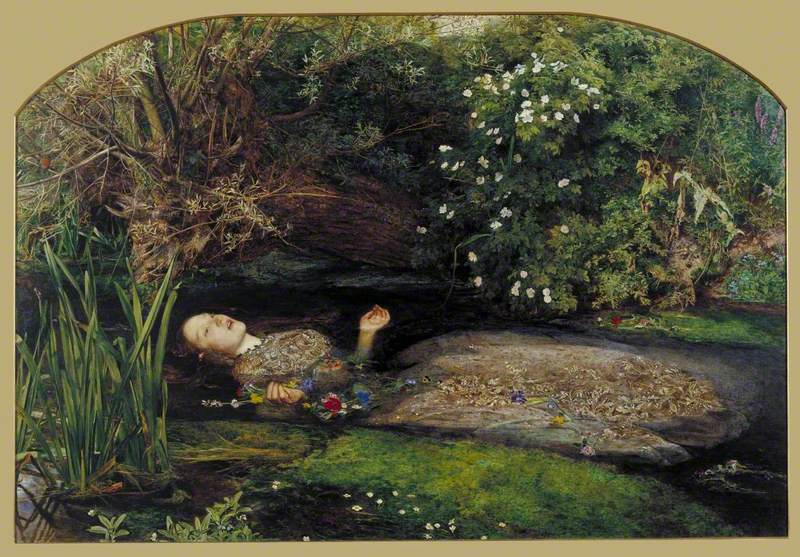

The Pre-Raphaelites have perhaps done more than anyone else in terms of crafting our popular conceptualisation of Ophelia. Most famous of these depictions is John Everett Millais' 1852 work Ophelia. In this work, Ophelia lies amongst the muddy riverbank, clutching flowers in her partly open hands, her head bobbing above the murky water. Her dress is rich and beaded, and seems to drag her down with the weight of the water. Her mouth is partially open, and her expression rather haunting.

When Ophelia's death is first relayed to the audience by Queen Gertrude, she talks about Ophelia drowning accidentally, after a branch from the willow tree breaks off, causing Ophelia to fall into the waters. Yet in the scene of The Gravediggers, Hamlet later contends that Ophelia must have purposefully taken her own life.

The mysterious death of Ophelia is reflected in her inscrutable expression in painterly representations of her – has she fallen accidentally, or are we witnessing her contemplation of suicide? Personally, I think an argument could be made for either, and for me at least, that is part of the appeal of the work. It allows you to pour your own thoughts and interpretations onto it, permeating into the piece.

Millais' work was an instant hit when it debuted at the Royal Academy, and remains perhaps both the artist's best-known work. Above all other depictions, it has defined the way we think of Ophelia popular imagination. It's because of this that we can see Kirsten Dunst recreating the pose in Lars von Triers' Melancholia (2011). When choosing to visualise the mental state of a bride who finds her wedding coincide by the end of the world, Von Tier reaches for the aforementioned associations that come with the character of Ophelia, and has Dunst sadly yet serenely floating, bouquet in hand.

View this post on Instagram

Millais' painting is significant not just as a watershed moment for Ophelia within popular culture, but also because it launched the career of the Pre-Raphaelites' most famous muse, the auburn-haired Elizabeth 'Lizzie' Siddal, who was also an artist in her own right.

Famously, in an unfortunate case of life imitating art, she almost died whilst imitating the death of Ophelia. Millais devised a system wherein the full bathtub she was posing in was kept warm by various candles. However, at some point during his work, Millais become so absorbed that he neglected to notice that the candles had gone out. After lying in the cold water for hours, Siddal subsequently became seriously ill and came close to death.

Her incandescently angry father had Millais pay for her doctors' fees after the threat of legal action. Nevertheless, Siddal becoming the defining face of the Pre-Raphaelite movement, the living image of what many artists, especially Rossetti (who went on to become her husband), sought to idealise in their work.

In turn, Siddal herself became a poet and artist, but her life and career were cut short by her death at the age of 32. Tragically, her death also imitated that of Ophelia's in that there was (and remains) dispute over whether the laudanum overdose that proved fatal was purposeful or accidental. Hundreds of years after her death, she remains the picture that comes into people's heads when they hear the name 'Ophelia', even to those who have never heard her name.

Miranda – The Tempest

1916, oil on canvas by John William Waterhouse (1849–1917)

Fittingly for his surname, John William Waterhouse depicts many water-bound women – be it naiads, mermaids, sirens, or even another Shakespearean heroine, The Tempest's Miranda.

So, it is unsurprising that Ophelia on the riverbank is a scene that he returned to several times throughout his career, in 1889, 1894 (the first image of the story), and 1910 respectively. There is something calmer about these Ophelias. The 1894 version could really by any young woman by the water – and indeed, the pose is very similar to his 1900 painting of a siren – as she serenely threads flowers through her hair.

Ophelia

1889, oil on canvas by John William Waterhouse (1849–1917)

Similarly, the 1899 version could simply be a nameless girl rolling around the riverbank quite happily. They are gorgeous images, but they do not tug on the emotions in the same way that Millais' painting does, and indeed could be taken as examples of a male artist romanticising Ophelia's death. I think there is an element of that, particularly with the 1899 painting, yet I also wonder whether – if we are to take Queen Gertrude's words at face value – maybe this is how Ophelia was in her final moments, prior to climbing onto that fateful willow tree. Maybe, if her death was accidental, she spent her time prior finally finding some contentment away from a chaotic and dangerous court. Possibly the flowers that garland her were momentarily a source of comfort, rather than a vessel for her outrage; perhaps she found the water calming.

Ophelia

1910, oil on canvas by John William Waterhouse (1849–1917)

Waterhouse's 1910, Ophelia, however, has a rather more concerned expression on her face. In classic Pre-Raphaelite fashion, he depicts her leaning her arm against a tree, as she holds flowers within her flowing gown. She stares, directly at the viewer, as if sending a warning or seeking help from us. This version of Ophelia, the troubled and so-called 'mad' wanderer along the riverbank, that people are more familiar with.

A recent example of an attempt to explore and reinterpret can be found in Claire McCarthy's 2018 film Ophelia, based on a novel of the same name by Lisa Klein, and starring Daisy Ridley in the titular role.

In this version, Ophelia (á la Juliet... except successfully) fakes her death with a potion that makes her appear dead, before later being released from her coffin. After the deaths of her father and Hamlet, the secretly pregnant Ophelia seeks out a nunnery she knows of from Gertrude and Hamlet, and raises her daughter away from the dangers of court life.

In other news: I watched the #OpheliaFilm on @NetflixUK the other night & absolutely loved it! The famous @Tate painting from the pre-raphaelite period is a personal favourite, though I often confuse it w/ another pic I ❤ of another doomed lady in/on water...The Lady of Shallott pic.twitter.com/NLZBtk74O4

— Dr. Rosalie Clarke (@RDC1987) May 10, 2020

The premise could have easily been a cheesy attempt to retcon a happier ending and more 'Girl Power'-esque role for Ophelia, but McCarthy's vision really works, and I personally ended up enjoying getting to spend time with a different version of Ophelia. Her appeal, I think, is that we don't really know what was going on through her mind, and this is perhaps why we turn to her and her unexplained death, again and again.

It's the tragedy and the beauty, yes, but also the question of who – who is the real Ophelia? Her role in the play is so clouded by others opinions of her, by Hamlet's paranoia and rejection, by her family, by Gertrude's account of her death. We don't have answers to these questions, but that doesn't mean we won't continue to ask them.

Chloe Esslemont, freelance writer and co-founder of TabloidArtHistory