The dignified regency exterior of Leicester's New Walk Museum & Art Gallery may seem an incongruous location for a collection of such verve and breadth as Leicester's comprehensive and acclaimed German Expressionist collection, yet the surprise that awaits is the more effective for it.

Leicester's New Walk Museum & Art Gallery

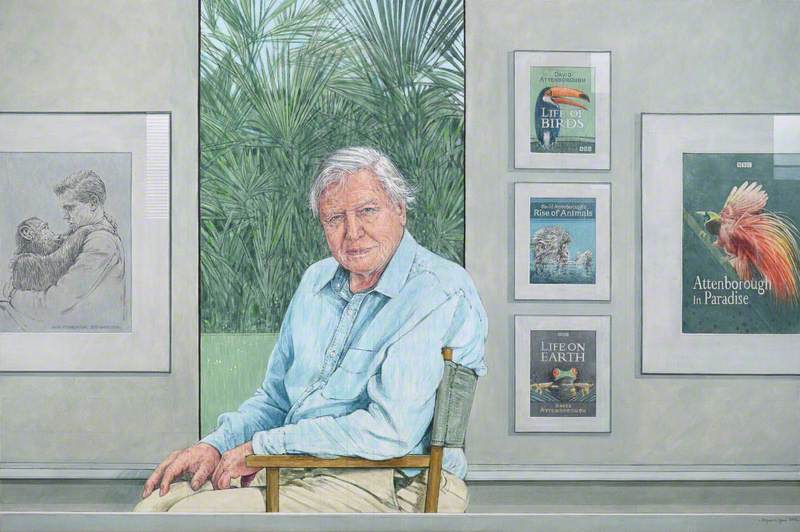

For enthusiasts of Expressionismus, the collection offers provocative food for thought, digested alongside a joyful display of Picasso ceramics, which until 2018 was installed in the gallery space directly adjacent (a collection formerly owned by Richard and Sheila Attenborough). Surprising it may be, yet Leicester, with its unwieldy cityscape and decidedly unromantic red-brick warehouses, makes a satisfying home for an art whose themes sprang from the environs of industrialism.

Its presence here is no accident, sponsored by the progressive vision of Arthur C. Sewter, the art assistant whose 'Contemporary Art' exhibition of 1936 included works by Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee and László Moholy-Nagy. From 1940 to 1946, Welsh-born Trevor Thomas was Curator-Director (having been deemed unfit for war service). From an anthropology background, he had spent time in New York installing an exhibition of African art, and acquainting himself with American and contemporary continental art. It was not a great leap, then, from 'tribal art' to the strongly expressive forms of modern German Expressionism, and he quickly set about accumulating a fine collection for the Leicester museum.

In 1944, following a successful exhibition of Polish art, Thomas mounted an exhibition of 'Mid-European Art', supported by the Free German League of Culture (FGLC). It included 62 works mainly by German (or formerly German-resident) artists, such as Emil Nolde, Franz Marc, Wassily Kandinsky, Lyonel Feininger, Hermann Max Pechstein and Erich Heckel.

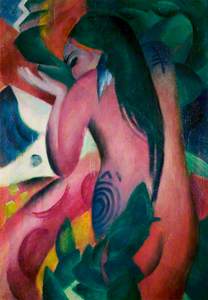

Of these, two oils were purchased for the collection – Feininger's Hinter der Stadtkirche (Behind the Church, 1916) and Marc's Rote Frau (Red Woman, 1912) – and two watercolours, Nolde's emphatic Head with Red-Black Hair (1910) and Pechstein's The Bridge at Erfurt (1919).

The 'Mid-European' works were loans from several émigré families but the majority, some 50 artworks, came from a vast collection of contemporary art (of more than 4,000 items), built up by the wealthy German-Jewish shoe-manufacturer Alfred Hess (1879–1931) and his wife Thekla (1884–1968).

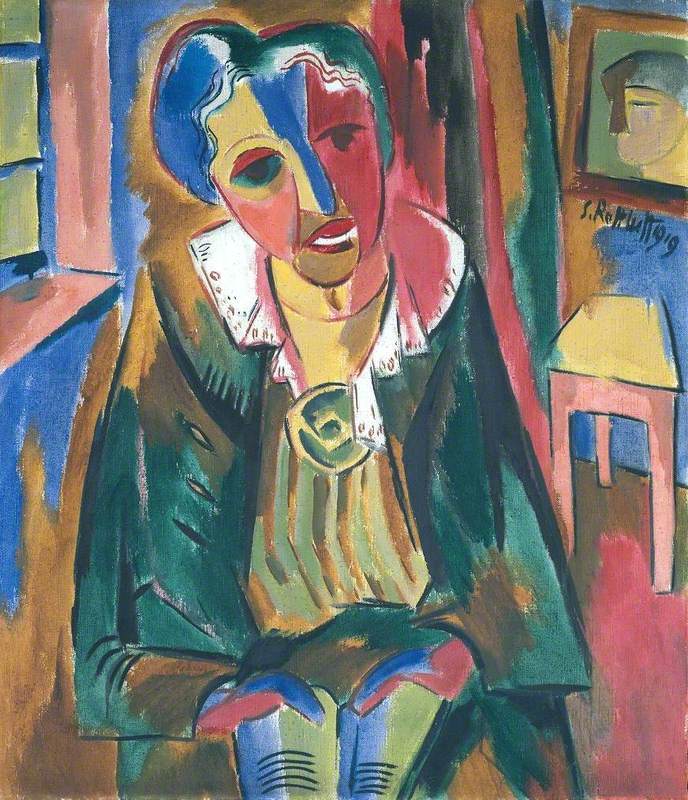

The couple regularly entertained many notable artists of the Weimar period at their home on the Hohenzollernstraße in Erfurt; a watercolour by Max Pechstein now in the Leicester collection shows a relaxed Alfred Hess at home smoking his favoured large meerschaum pipe.

The Smoker: Portrait of Alfred Hess of Erfurt

1919

Hermann Max Pechstein (1881–1955)

In the early 1920s, the Hesses formed a close alliance with Walter Kaesbach, director of Erfurt's Angermuseum, donating generously to the museum.

Following the early death of his father in 1931, Alfred's son Hans inherited the family collection. Shortly after the National Socialists seized power, in January 1933, Hans left Germany for the UK, while his mother Thekla remained behind to administer their collection.

In August 1937 the Nazis, then rampaging against what they termed 'Degenerate Art', confiscated some 800 artworks from Erfurt. Thekla, fleeing to Switzerland, was, like many other refugee émigrés, forced into selling off artworks to support herself, leaving others in store with the Cologne Art Association, some of which were looted. In 1939 Thekla moved to England to rejoin her son Hans, who, briefly deported to Canada as an 'enemy alien' and subsequently an agricultural labourer in Leicestershire, was a founder member of the newly established FGLC, and from 1944 to 1947 assisted Thomas as Deputy Keeper at Leicester's museum.

Over the years Leicester's collection has expanded through purchases and bequests to become one of the outstanding collections of German Expressionism in the world. Works by Karl Schmidt-Rottluff were bequeathed by art historian Dr Rosa Schapire in 1954 (whose 1919 portrait by him now hangs in the Tate).

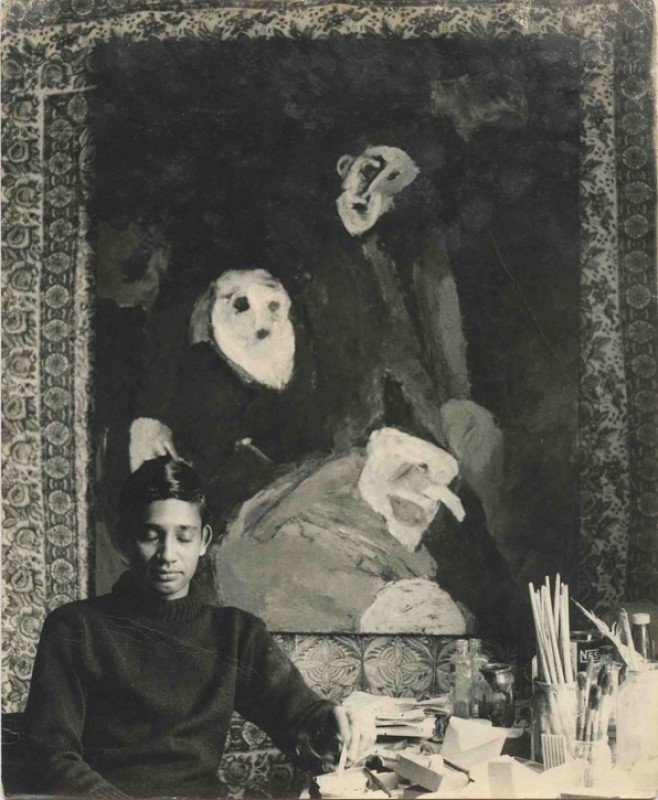

More than 60 items were donated by Michael Brooks in 2009, his initial interest in German Expression reportedly inspired by the film The Cabinet of Dr Caligari. More recently, a number of works by Marie-Louise von Motesiczky, including four oils, were donated in 2018 by the Charitable Trust in her name.

There are currently some 86 paintings and graphic works displayed in 'The Total Artwork' Expressionist gallery, arranged in roughly chronological order by theme, and covering the key developments around the movement.

Lovis Corinth's stately portrait of Carl Ludwig Elias in his sailor suit contrasts with Max Liebermann's French-influenced portrait of his granddaughter alongside, as examples of German Impressionism.

Die Enkelin des Künstlers mit ihrem Kindermädchen

1919

Max Liebermann (1847–1935)

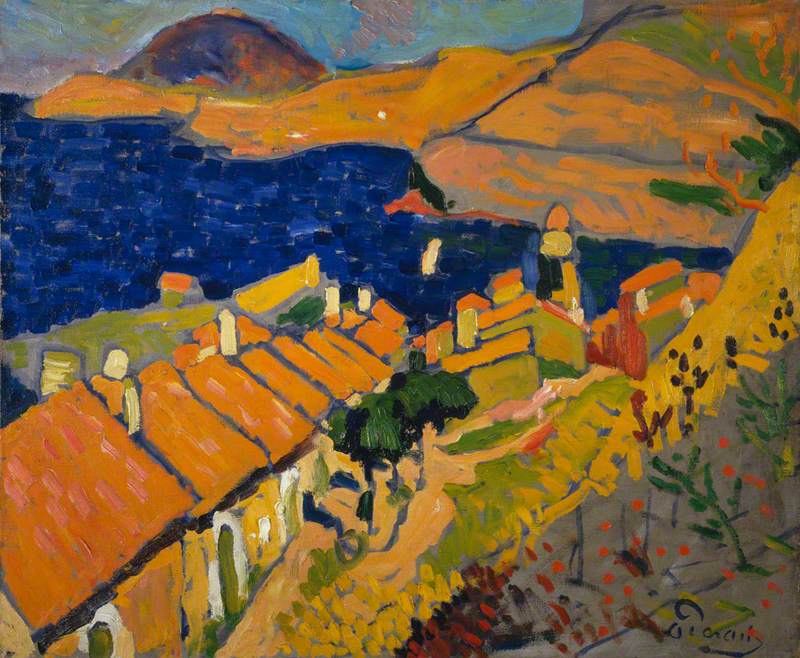

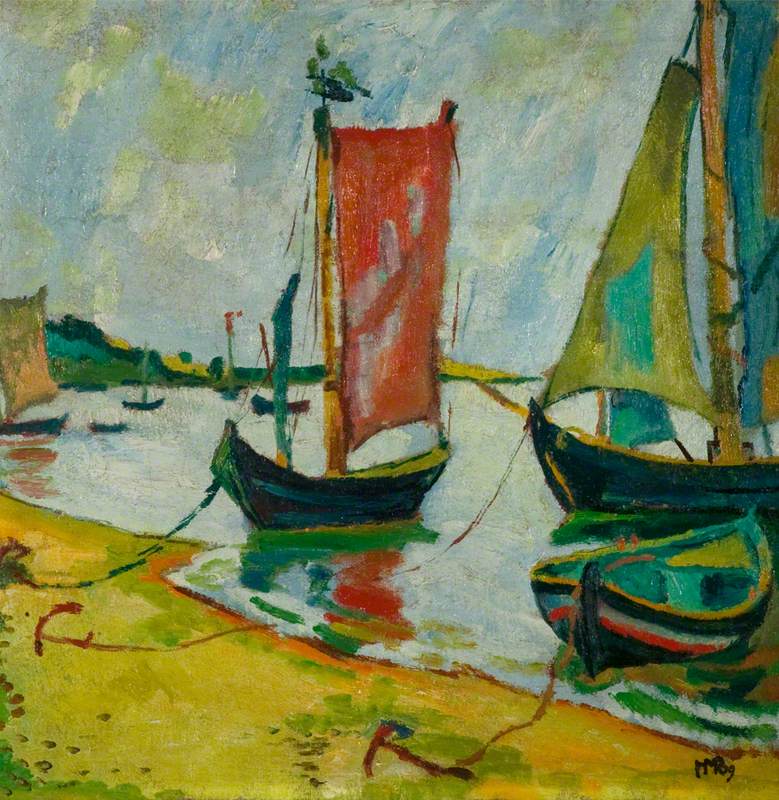

Artworks by the primitivist group Die Brücke (The Bridge) include vibrant works such as Max Pechstein's watercolour of Hess (shown above), and his Nidden Coastline with Fishing Boats (1909), which employs an expressive vigour akin to the work of the Fauves (literally, 'beasts') such as Matisse and Derain, then working in France.

Nidden Coastline with Fishing Boats

1909

Hermann Max Pechstein (1881–1955)

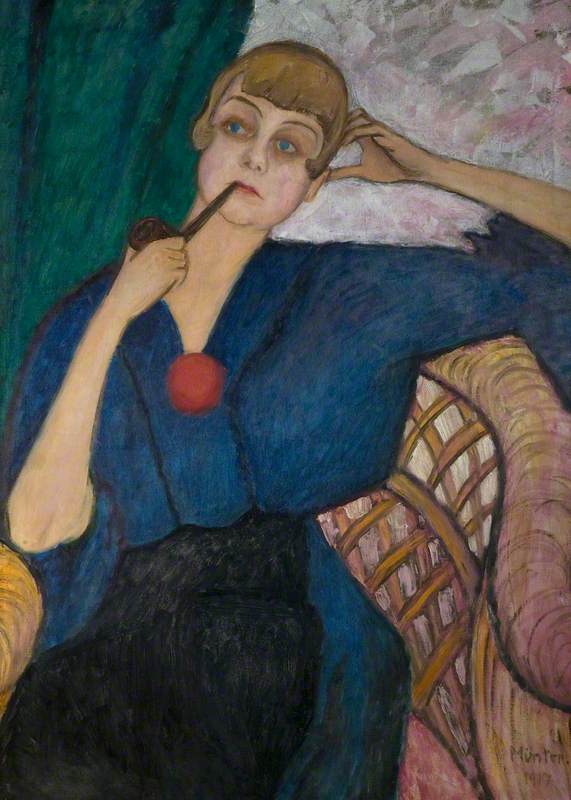

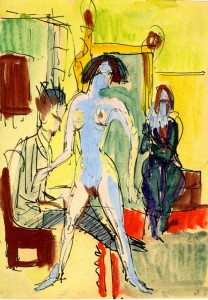

Der Blaue Reiter (Blue Rider), an association flourishing from 1911 to 1914 of mostly Russian-born artists in Munich, are represented with oils by Franz Marc, whose striking Rote Frau is noted above, and Gabriele Münter's languid portrait of Swedish writer Anna Roslund-Agaard (1917), with blue abstracted gaze as she smokes her pipe.

Münter was a partner of Russian émigré Wassily Kandinsky, whose joyful colour woodcut Lyrical (1911) is shown nearby, together with drawings, gouaches and prints by other members of this group such as Alexei von Jawlensky and Erich Heckel.

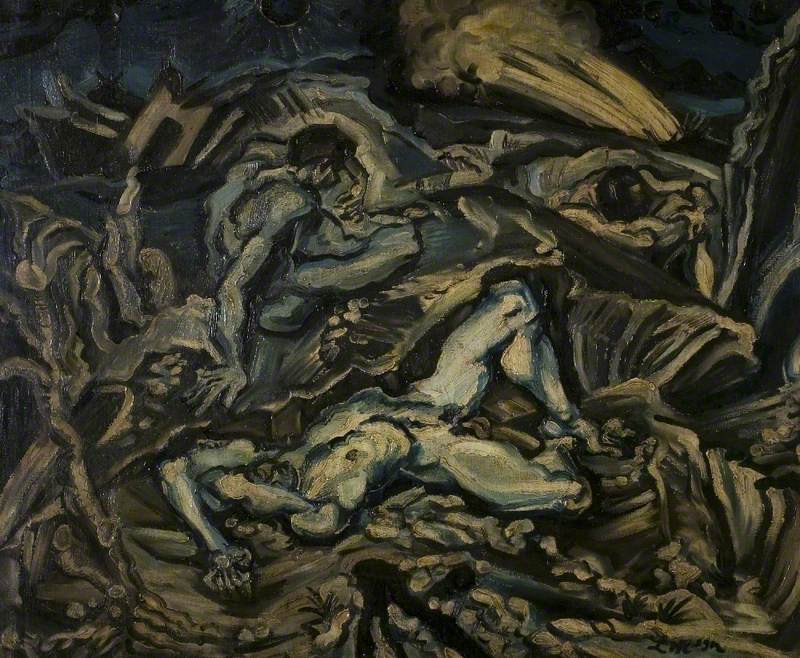

In startling contrast, curated under the heading 'Expressionism and War', we encounter the brutal work of Ludwig Meidner, whose Apocalyptic Vision (1912) harks back to medieval Last Judgments, while recalling us sharply to the threat of approaching war.

Compositionally, and with its viscous impasto, it portends of the worst horrors of the trenches of just some four or five years later; while figuratively and in tone it resembles some of the expressionistic works of early Cézanne. Ludwig von Hofmann's Zusammenbruch (Breakdown, c.1918) nearby depicts men cowering under the relentless assault of an unknown oppressor.

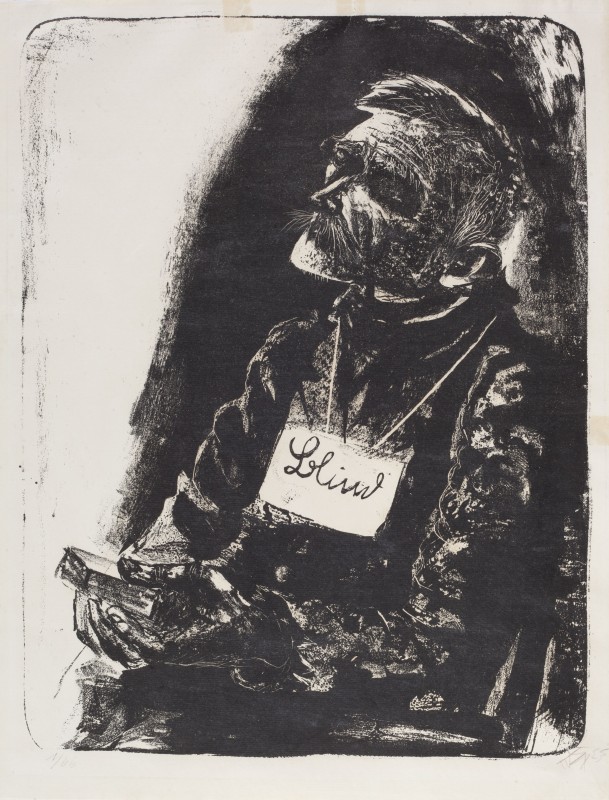

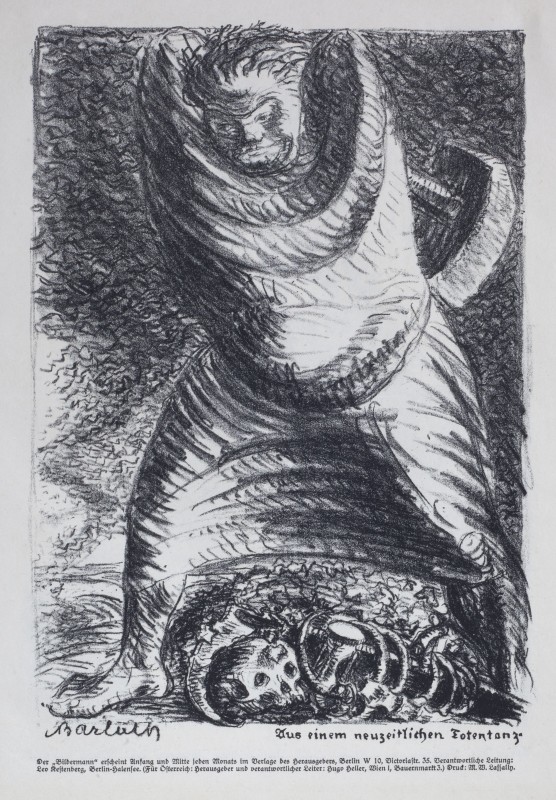

That they cower from might be envisioned in a powerful small lithograph by Ernst Barlach nearby, his From a Modern Dance of Death (1916), from the journal Der Billderman. In this grim scene, war is depicted as a monumental ogre, crashing down upon a heap of skeletons with a sledgehammer blow. One hears the noise and senses the vibration.

From a Modern Dance of Death (Aus Einem neuzeitlichen Totentanz)

1916

Ernst Barlach (1870–1938) and Paul Cassirer (1871–1926)

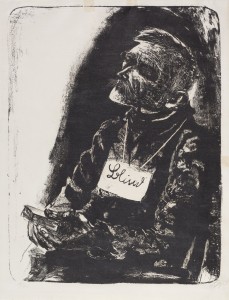

The silent, bleak aftermath is presented nearby in another small litho, Otto Dix's resigned, beseeching Blind Man (1923).

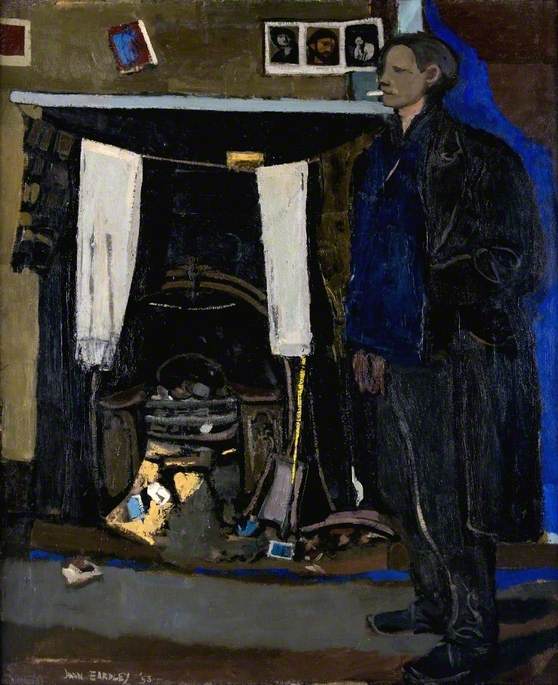

'The World of Shadows and Light' shows what awaits after the dust has settled. Works grouped here are from the so-called Weimar years, of 1918 to 1933, reflecting the 'Neue Sachlichkeit' ('New Objectivity') realism of the post-war era.

Ernst Neuschul's biliously coloured Messiah, with manic eyes and bared teeth, stands amid verdant hills upon a road leading to Lord-knows-where: ostensibly a self-portrait, celebrating art's power (his cocky self-assurance bringing to mind the young Wyndham Lewis), it might equally offer the prospect of leaders who might step into a political vacuum.

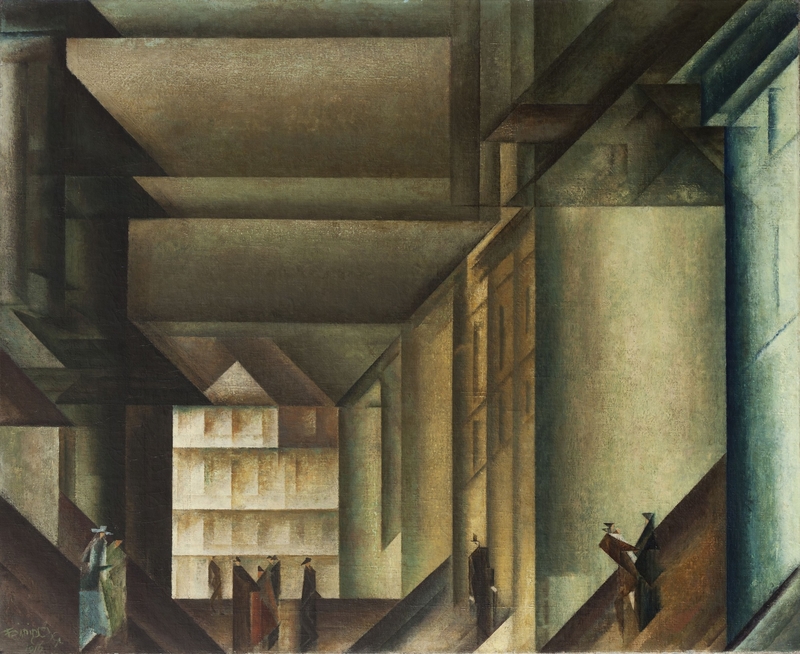

Hinter der Stadtkirche (Behind the Church)

1916

Lyonel Feininger (1871–1956)

In contrast, Feininger's Hinter der Stadtkirche (Behind the Church, 1916) could represent those who slink away into the backstreets: its geometric precision offers respite from the emotional excesses of the war years.

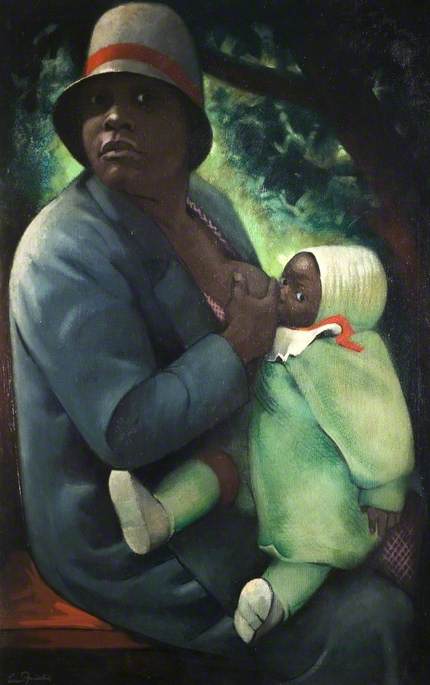

Neuschul's watchful Black Mother (1931), disturbed while breastfeeding peaceably on a park bench, might be seen as a comment on the growing National Socialist threat.

Indeed this painting, and others by him depicting those on the margins of German society, incensed the Nazis – reportedly leading to a shouting match between the artist and Goebbels in the Reichskunstkammer. Several of Neuschul's paintings, like other 'Degenerate' artworks decried by the Nazis for 'perverting German culture', were in February 1933 burned or destroyed on Goebbels's orders.

Lotte Laserstein's portrait of her friend Gertrud Rose in The Yellow Parasol (1935) recalls the naturalism of the pre-Expressionist period, and, with its decorative Japonist sunshade and Fair Isle pullover, looks to a world beyond Hitler's Germany.

As war broke Laserstein, a German Jew, fled to Sweden.

Frau Im Café (Woman in a Café: Lotte Fischler)

1939

Lotte Laserstein (1898–1993)

Her portrait Woman in a Café (1939), of Lotte Fischler, whose husband had assisted Laserstein with an exit visa, reflects her gratitude for their help with her efforts to rebuild her life as an exile.

Henriette von Motesiczky with Dog and Flowers

1967

Marie-Louise von Motesiczky (1906–1996)

Newly acquired works by the Austrian artist Marie-Louise von Motesiczky, like the tender 1967 portrait of her elderly mother Henriette with her greyhound Wixi, show the continuation of this expressionist vein beyond the Weimar years, in particular through the influence of Oscar Kokoschka (OK).

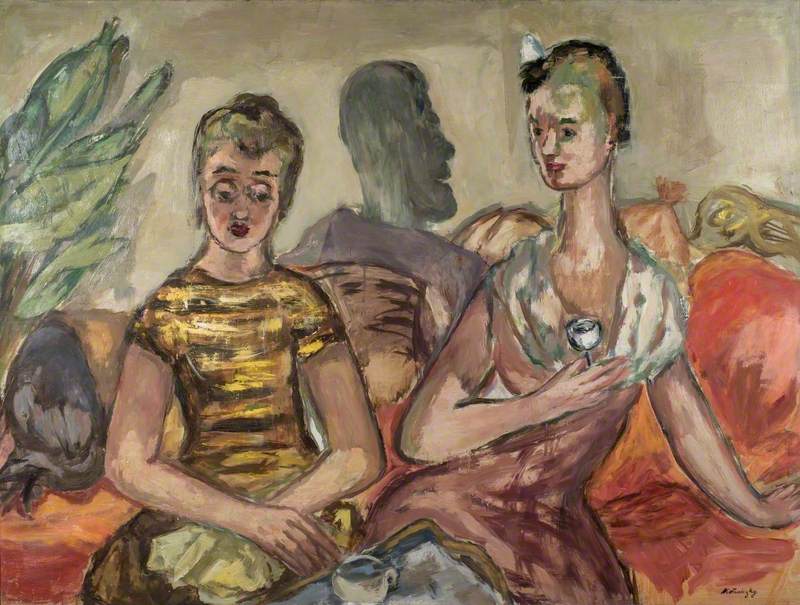

Nearby, in a modern-day conversation piece, Two Women and a Shadow (1951), Motesiczky portrays herself sitting beside OK's wife Olda, with the shadow of OK's head looming between.

Heady, provocative, at times lurching towards madness, and leading, ultimately, to realignments and reflection, German Expressionism effectively mirrored the zeitgeist of its age – and holds up a sobering mirror to the volatility of our own.

Sara Ayad, independent art researcher