He famously wrote, 'I cannot begin to argue the art for art's sake argument in a situation where children are being shot and killed for protesting at injustice'. The artist responsible for that line – a charge with serious force and clout – was Gavin Jantjes.

Jantjes was born in 1948 as South Africa lay in political turmoil. Rebellion was a necessity for many children born after the fall of the United Party who could not make peace with those seduced or acquiescent to the demands of Apartheid. In adulthood, he claimed that representation of this oppression as well as slavery was out of focus at the edge of history, which was at once the truth and a potent symbolic statement. As the artist averred in an interview with Marlene Smith, 'all of this stuff was just washed over, history was just passed over'. Such an atmosphere of smothered dread and secrecy could only be broken by defiance

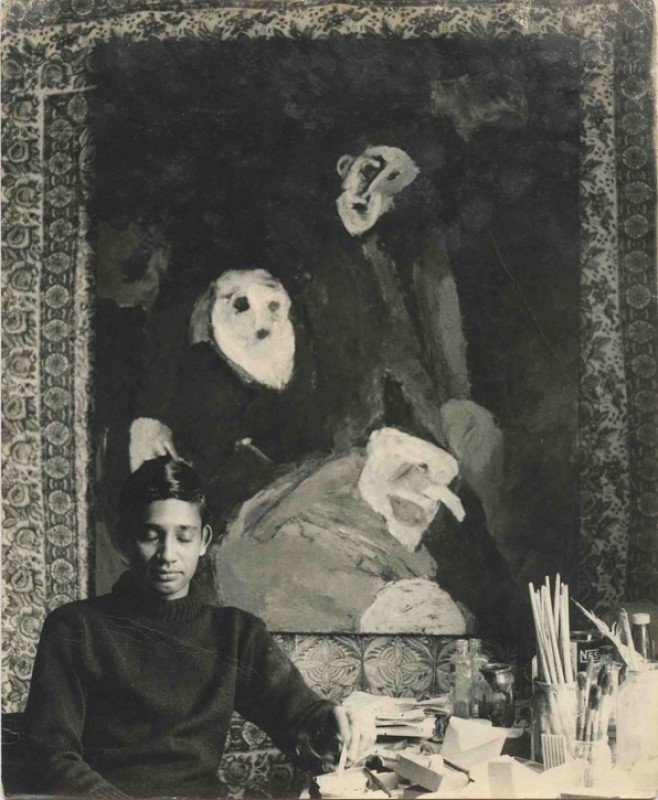

Jantjes's flair for narration combined with that compulsive need to expose the turmoil that others deemed too troublesome to contemplate was a means of resistance. 'Three hundred million Africans [enslaved]' he told Smith in 2016, 'and nobody's even put up a plaque', and they needed to be chronicled. Certain of his contemporaries would choose similar methods to deal with these toxic feelings that vexed relations between memory and history. Both Joseph Beuys and Anselm Kiefer were known to Jantjes as their world overlapped with that of his artistic environment in Hamburg in the 1970s. In reckoning with the traumas of post-war South Africa, he dedicated himself to a no less subversive neo-expressionist mode of painting.

A stark barren scene from the first work in the 1986 'Korabra' series catches some of this historical trauma. A metallic shape sat on the horizon line like it's an ominous spectre, the blue anvil surrounded by a ring of wooden stakes, looping round it like a threatening or violent trap as the dirtied block occupies a semi-circle cut into the brazen soil. The spikes hover – a menacing image – and the anvil looms on, its connotations of slavery.

At 26, Jantjes received an early warning from the Apartheid authorities that there was no way his activism could support more than a few years of asylum in Germany but he paid the claim no attention at all. Refuge was awaiting him, living in self-imposed exile, but there was no way he would abandon his dissident strategies, documenting the inequalities of the past and destabilising dominant visual languages. Without all of those approaches, making art would have felt oppressive anyway.

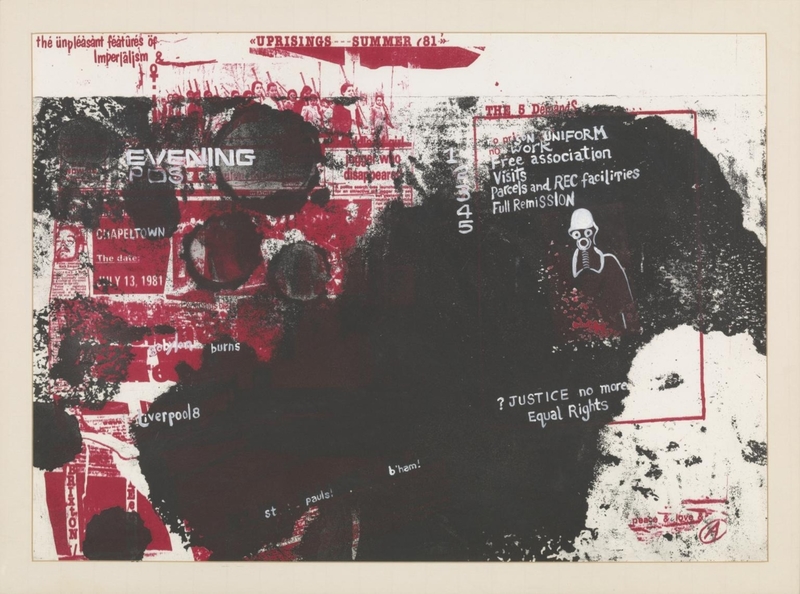

That was when he was making his major work, A South African Colouring Book (1974–1975). Pulling up memories from recent history, Jantjes arranged a series of twelve panels showing silk-screened images of South African life for Black people under apartheid. Caroline Collier recalls seeing another set of works by Jantjes at the Edward Totah Gallery in London: these works are 'as much a search for a painterly language capable of expressing his vision of the present and his feelings about the past, as it is an examination of the bitter facts of slavery'. 'Korabra' was the title of this long-planned series of seven paintings.

Seeing these works in 1986 there could be no moments of peacetime repose. The melancholic subjects of the second work in the 'Korabra' series are floating across some uncertain zone in between a classical temple and a pair of pyramidal buildings with their angular façade and muted palette. In her 1986 essay, 'Korabra: Paintings by Gavin Jantjes', Collier describes how the word korabra means 'to go and come back' to the Akan people of Ghana, eager to return home after a long journey. An émigré painter, Jantjes's transnational travels – from South Africa to Germany and arriving in Britain through these migrations – provide a literal illustration of the rubric to his work. Catch the passage in progress: three boats shaped like coffins sail over turbulent waters (askew and fuzzily interrupted by Jantjes's coating of sand and pigment). Death disturbs this journey.

But how to interpret the nomadic within this series of works: what if, as Collier writes, it was a search for a painterly language? David Dibosa averred that the highly wrought surfaces of the series painted by Jantjes were inspired by a prominent group of post-war German artists. (With their raw colours, embrace of memory and narrative, the 'neo-expressionists' were an inevitable influence for Jantjes who studied under Beuys.) Seen as a cataloguer of historical trauma, he proves every landscape contains a narrative.

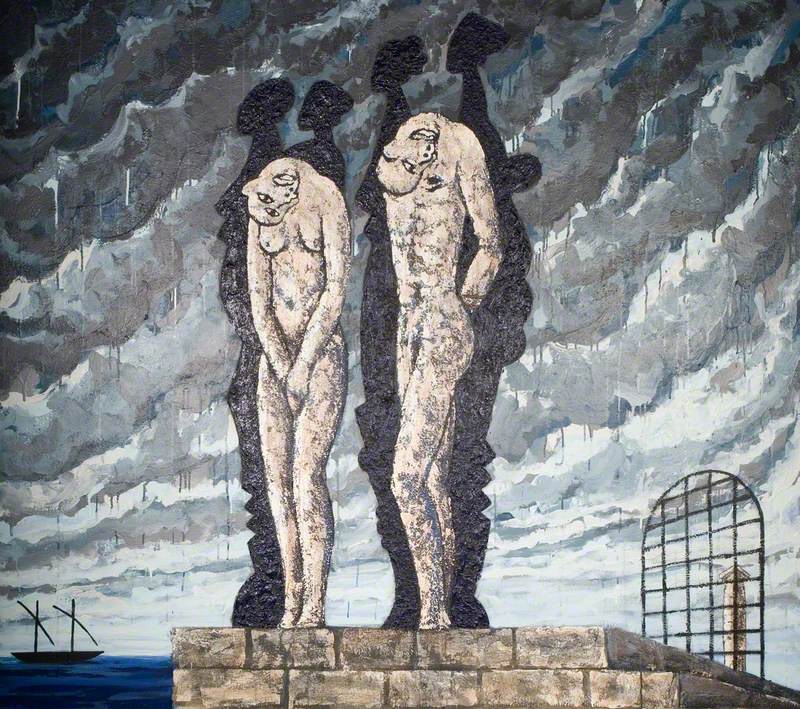

Untitled

(third in the 'Korabra' series) 1986

Gavin Jantjes (b.1948)

Neo-expressionism remained a fascination for Jantjes in his painting because they negotiated a similar suffering in their work as him, confronting the history of violence in the wake of the Second World War. See Jantjes's third in the 'Korabra' series, standing figures on a promontory of cut stone. This skinny pair, with their hands chained, charred skin and heads dangling hit us with a macabre stare. For Jantjes, this incident is a violent moment of a historical event, calling in the pairs' shadows of their noble past against the thunderclouds with their thick, gestural strokes of blue-grey all daubed across the canvas. As the painter Anselm Kiefer states in a 2021 interview, remembering and reworking German cultural trauma, 'objective history doesn't exist, it is often times written by the victors.'

Psychological and historical realities – that many would prefer not to acknowledge or imagine at all – are seen in both Kiefer's and Jantjes's work. One of the most painful paintings in this series demands contemplation of how the troubled surfaces of the pair's bodies work alongside the disturbing content of the image. At play in fleshy and bruised tones with the grittiness of sand, the bodies bear an expression of macabre decay, upright yet slumped as their mouths hang open. What makes the picture plane so textural is doubtlessly the way in which Jantjes adds pieces of tissue paper, clotting the paint.

His paintings which are uninhabited by any figures still broach more unsettling ideas. Maybe thinking of Kiefer again, Jantjes painted the fourth in the 'Korabra' series. Covered with chalk-like crucifixes, its dark lines of earth freshly dug, the surreal landscape suggests an undulating memorial field. Far-off clouds are coated in dark blue and lilac pigment, sand, sugar and cotton wool and the shape of a guitar looms over the empty countryside.

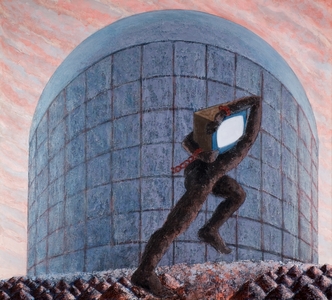

Jantjes spoke of wanting a less knowing relation to painting landscape, and continually erased what he thought was its specificity. He adopted Caribbean poet Edward Kamau Braithwaite's notion that a good poem is one that creates myths. His use of symbols of his own making – coffins as ships, a nude figure with a television for a head, an enlarged anvil – and of a newly envisioned mythic space had seemed like a reliance on myth and poetry but came to seem an evocation of the alienation inherent in enslavement.

Untitled

(sixth in the 'Korabra' series) 1986

Gavin Jantjes (b.1948)

Art historian Dibosa sensed this experience: 'Through these works, Jantjes creates a cultural imaginary of Britain that can include slavery rather than exclude it'. If so, the artist wanted to return to this disturbing history on new terms. The sixth work in the 'Korabra' series shows a defiant statue squeezed into the frame of a red and black quagmire. Covered with plaster-like, sandy paint, its arms held tight, the figure suggests a prehistoric humanoid. A far-off volcano looms over a molten seascape. Everywhere, Jantjes surveys his landscape like someone in the middle of a dissociative dream.

The cut-and-mix logic was always a way for Jantjes to problematise mediated imagery (see the intermedia framework of newsprint, photographs and hand-written text comprising A South African Colouring Book) but by the inauguration of the 'Korabra' series, making art had become twisted up with other compulsions: to open a fresh vantage on cross-cultural processes of hybridity, combining a coarse neo-expressionist style with the disturbing imagery of the transatlantic slave trade, to reveal the firmly established transculturation in the long-range history of art.

The most eerily equivocal of landscapes is the very last one in the series: a cylindrical structure, the nuclear power plant dominates the ground of conical mounds covering the lower half of the canvas. Here a figure moves across the painting with a broken chain around each wrist and a television set. It's hard to tell whether the TV displaces the male's head or rests upon it, which serves to further implicate ambiguity with its screen blank, purposefully, to mirror the sky's afterglow. The body runs, powerfully in the pink sunset, with freedom somewhere beyond those conical mounds.

Matthew Cheale, writer, editor and art historian

This content was supported by the British Art Network's Black British Art research group

Further reading

Celeste-Marie Bernier, '"A Freak in the Blizzard of the White Man's Gaze" – Black Absent Presences and Present Absences', Stick to the Skin: African American and Black British art, 1965–2015, University of California Press, 2019, pp.161–176

David Dibosa, 'Gavin Jantjes's Korabra Series (1986): Reworking Museum Interpretation', Art History, vol. 44, no. 3, 2021, pp.572–593

Also Marlene Smith, Gavin Jantjes interview, 17th March 2016 (BAM20161201). Unpublished, quoted in Dibosa above

Kobena Mercer, 'The Longest Journey: Black Diaspora Artists in Britain', Art History, vol. 44, no. 3, 2021, pp.482–505