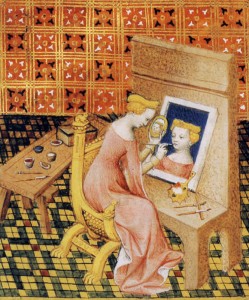

Originating in northern Europe in the 1600s, still lifes by male painters reproduced elements of domestic space while avoiding the depiction or celebration of the uninteresting realm of femininity. A few gleaming objects – no mess, no emotion, nor any trace of function.

The planning and organisation of where things were bought, stored and eaten did not matter. Instead, food articulated wealth, or mapped the trade routes taken to the table; in darker moods, possessions spoke to the brevity of life. Painterliness was more of interest than purpose: note the stippled surface of a cucumber, the frills of cabbage leaves like petticoats, or the cut melon's study in contrasts.

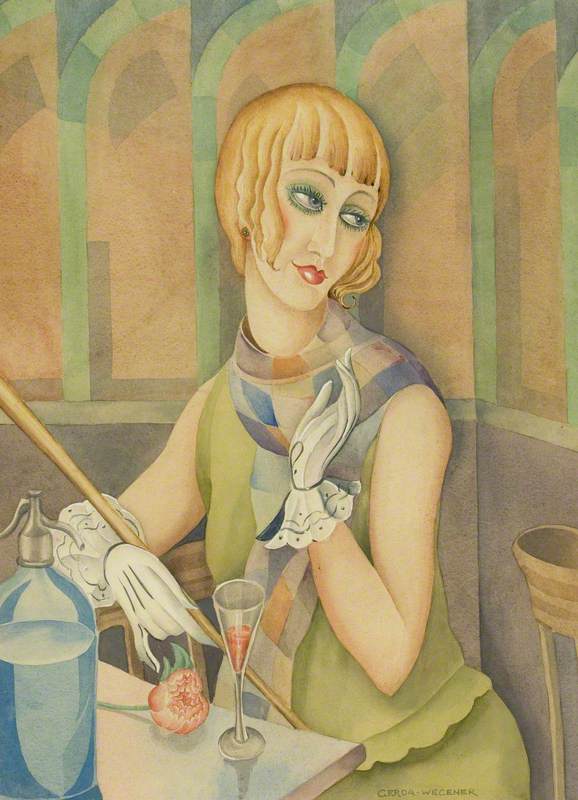

For women artists in the early twentieth century, still life remained a medium through which to explore aesthetics and politics, but to this established repertoire, they added an exploration of the uneasy relationship between the public and private spheres, gender and value, lived experience and aesthetic form. The domesticity these women's paintings took as their subject had once been an instrument of oppression, precisely the cause of their careers as artists being curtailed.

Yet on canvas, a kind of reversal occurred. Definitions of the value of the home no longer came from the outside – the patriarchal institutions that wanted to preserve women's subservience – but from within. A new moral universe was founded, constructed by women and circulated by their creative work, with an emphasis on freedom of thought, hope, and a suddenly boundless aspiration.

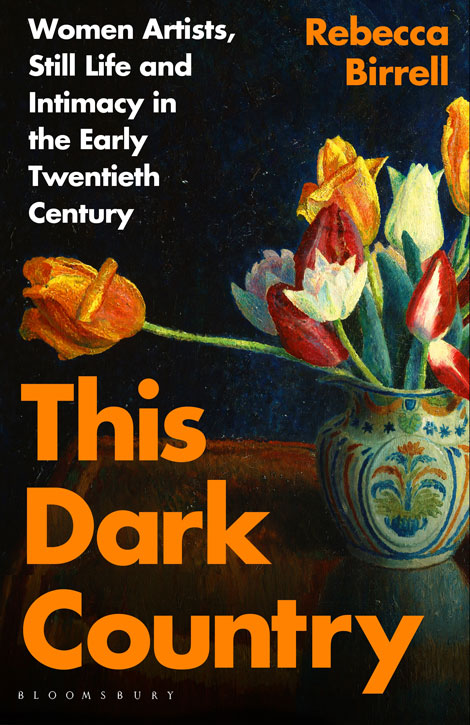

This Dark Country: Women Artists, Still Life and Intimacy in the Early Twentieth Century

At the same time, and through an innovation that their male forefathers never conceived of, still life became a repository for daily experiences, a way of summarising the diverse parts that made up their lives. This rebellious new use for still life is what This Dark Country: Women Artists, Still Life and Intimacy in the Early Twentieth Century is about, and the sustained focus on the genre by six women artists in particular.

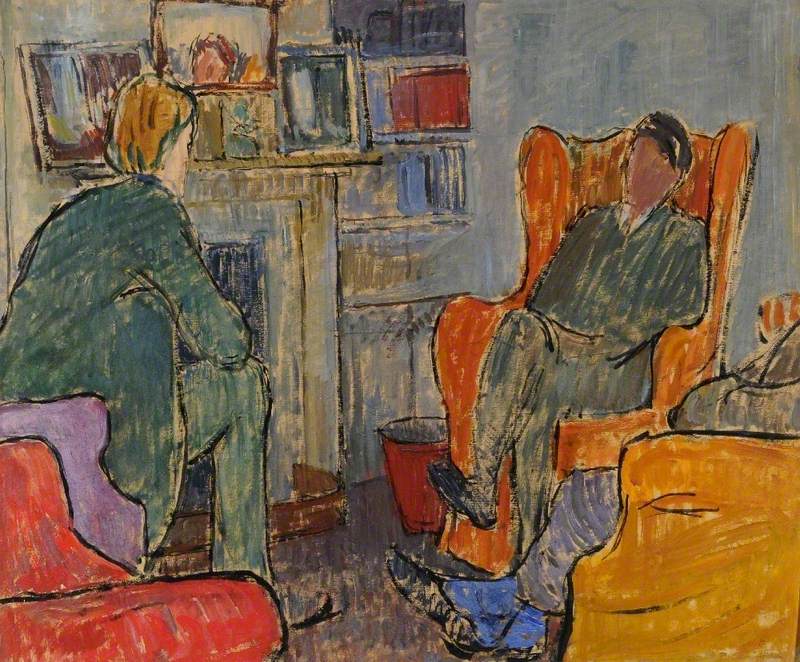

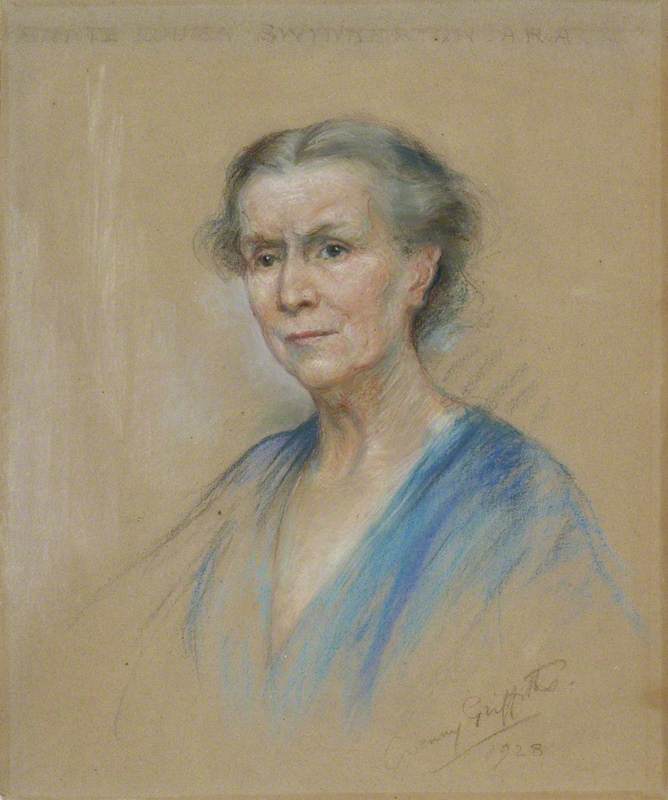

Ethel Sands

A high society hostess dismissed by her contemporaries as shallow and sexless, Ethel Sands (1873–1962) painted luminous canvases addressed to the protected life she had built for herself and her partner, the artist Anna Hope 'Nan' Hudson (1869–1957).

In Still Life with a View over a Cemetery, elegance and connoisseurship are embodied by precisely matched china and glass, ostensibly trivial concerns that are shown to coexist with a consciousness of death, the crosses marking graves that the curtains open onto.

The contrast questions assumed divisions between the serious and the frivolous, depth and surface – categories often synonymous then with masculine and feminine – and also implies a possible function for Ethel's preoccupation with style: with attention consumed by matters of taste and interior curation, rooted in the everyday and her immediate surroundings, mortality could be at least partially kept out of sight.

Interior with Still Life and Picture of the Madonna and Child

Ethel Sands (1873–1962)

More than simply a record of her home, Ethel's still life – in common with many women artists – is in fact a self-aware statement on the genre itself, which has long tackled ideas about existence and its essential ephemerality.

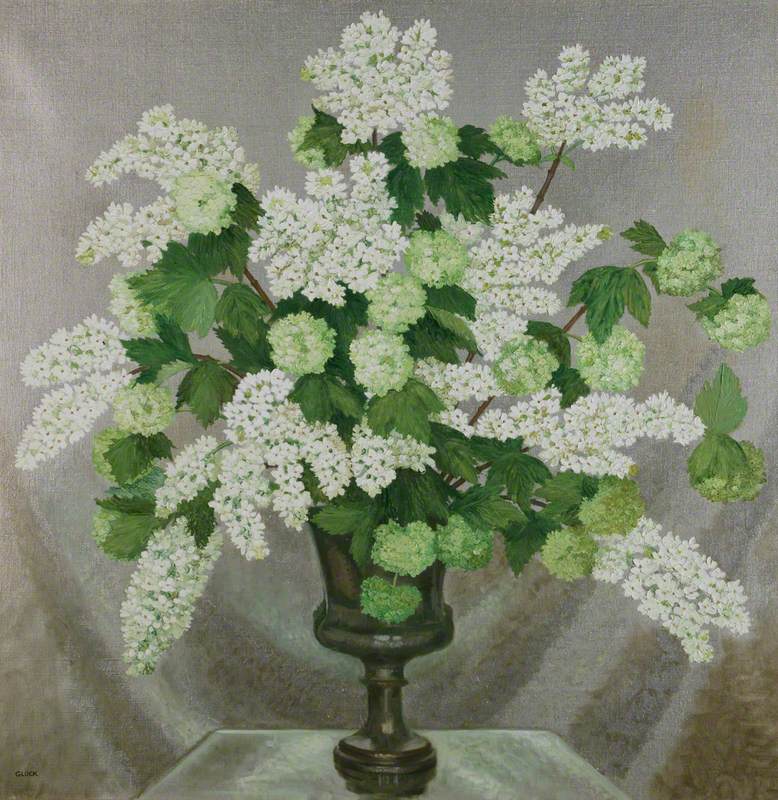

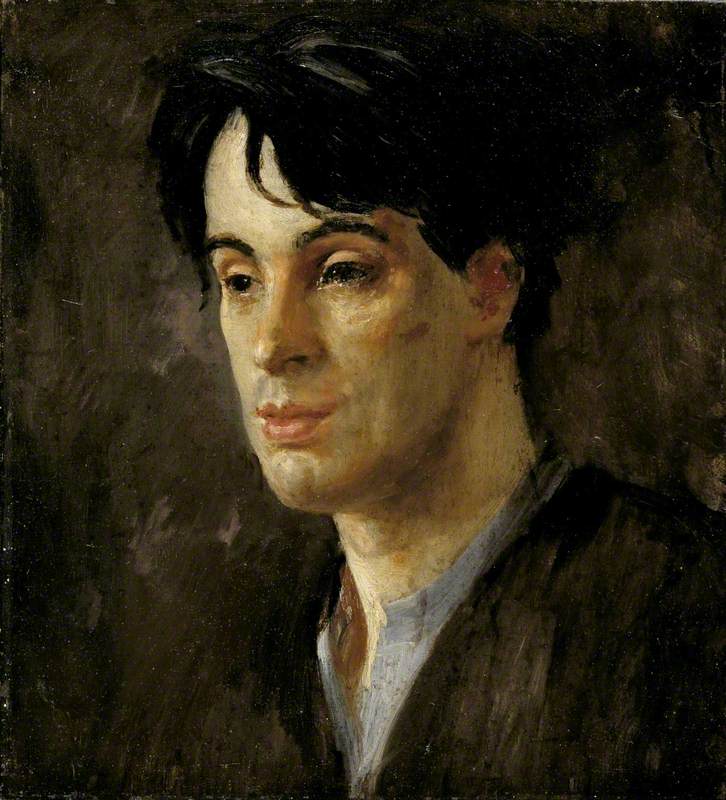

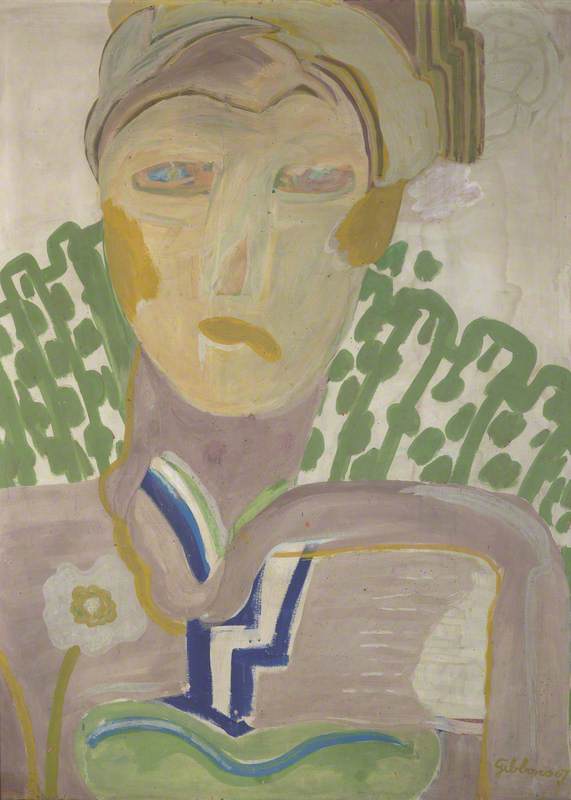

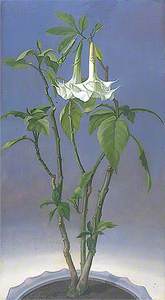

Gluck

For Gluck (1895–1978), gender was a fluid, experimental, stylistic and epistemological practice tantamount to a dynamic work of art. Gluck's experiments in still life reflected the artist's subversive thinking and part of a broader artistic project interested in bodies and identities (and the scant available means of representing them).

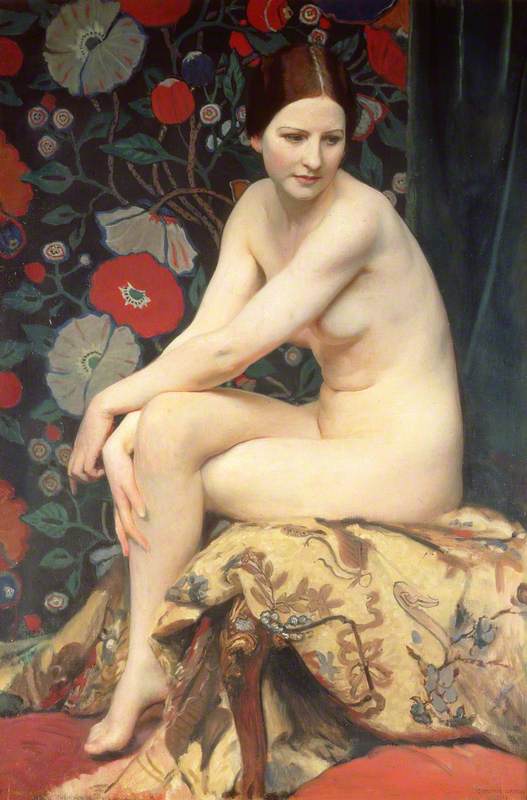

Bypassing the habitual objectifications of the nude, Gluck also decided against portraiture, regarding its simplistic use of the body as a transcript of character. Instead, Gluck pursued a series of flower works to create something entirely new: an attempt to convey the visceral, sprawling experience of embodiment.

With their emphasis on recurring shapes, precise movement and opaque patches of colour, these works were about reproduction, the ubiquitous and unending processes that underlie them, and about boundaries and flow – of blood and water and breath and hormones – all the growths, losses, and unsteady equilibriums unfolding across networks of interconnected systems that constitute the foundation of our lived bodies.

These energies, with all their dynamic and knotted and mysterious force, were what the traditional nude did not acknowledge – and they're not only explored in Gluck's flower paintings independent of any particular self, but also, and perhaps more radically, of any single gendered or sexed body.

Gluck's flowers borrow terms from the masculine and feminine, never bothering to heed anything so banal and restrictive as the binary system of gender or sexual difference, and instead these works naturalise an environment in which the connection between bodies and identities is complicated, slippery and expansive.

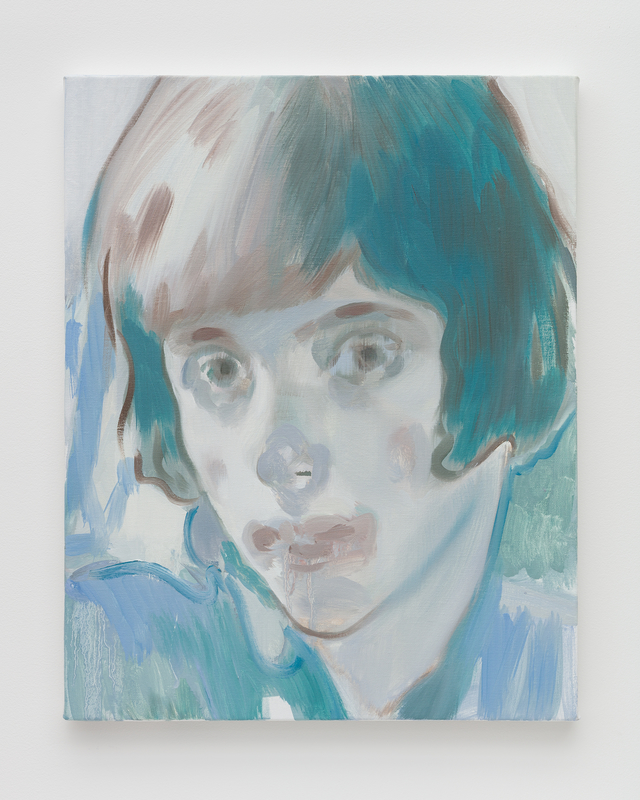

Gwen John

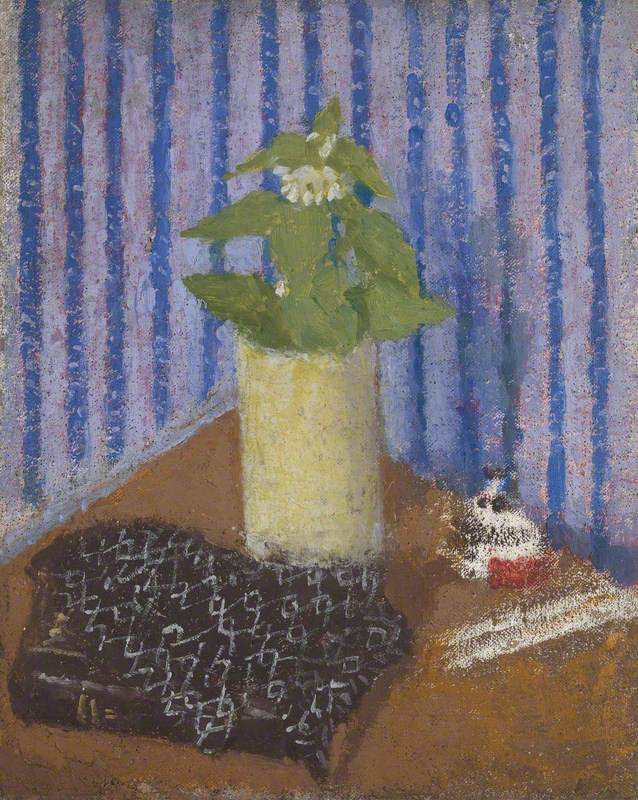

For the Welsh artist Gwen John (1876–1939), art was an intense spiritual undertaking that encouraged explosive connections between painting, writing and desire. There are around a dozen paintings that place the viewer inside John's room, and many more that are not explicitly studies of an interior – portraits of women, for instance, take her room as a backdrop.

Rooms are observed, cropped, refocused, and rearranged. Each room represents a slight but tangible reconstitution of another composition, a hand twisting a kaleidoscope. Anchored into a particular place, repeatedly guided towards the same surfaces and shapes from different angles, the stuff of life itself is pared back to a simple scaffold, and John studies the unexpected joints, the meeting of objects and hours on which so much depended, the parts of her own everyday structure which bore the most weight.

The subversive charge of this work was subtle but no less transformative: John's work paid attention to a domestic defined not by the needs of the conventional familial unit, by self-sacrifice and interminable labour, but by solitude, pleasure and art, and in doing so made space for and elevated a different kind of life for women.

Still Life with a Prayer Book, Shawl, Vase of Flowers and Inkwell

late 1920s

Gwen John (1876–1939)

Nina Hamnett

The paintings of Nina Hamnett (1890–1956) were as crucial to her vocation as her flamboyant social performances, each articulating something about the transgressive charge of lone women captivated by pleasure and excess. Traditional still life celebrated wealth and status, displaying opulent tables laden with expensive food and wine.

However, Nina's revisions to the genre were always situated within the precarious rented accommodation she lived in alone throughout her life, and did not shy away from the material realities of those rooms. This still life is typical of her sombre, simple iterations of the genre, and despite its quietness as a painting, its mundane, even claustrophobic setting constitutes a daring resistance to the heterosexual bourgeois social ideal she had been raised to desire.

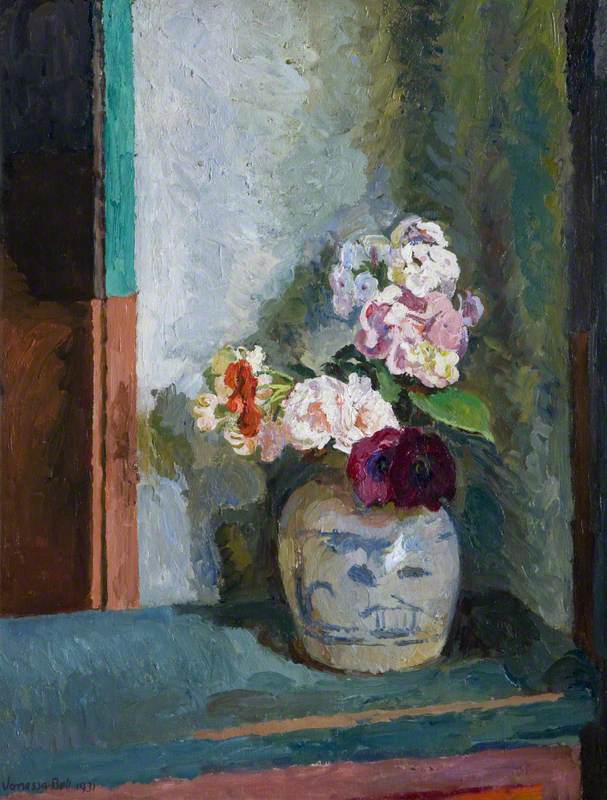

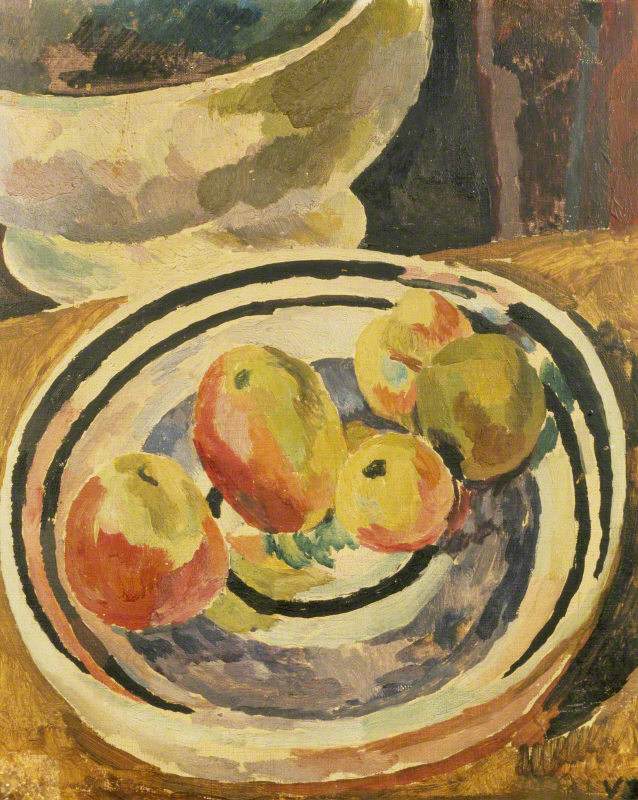

Vanessa Bell

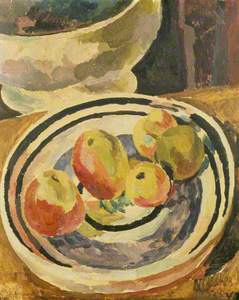

Like the other women artists featured in This Dark Country, Vanessa Bell (1879–1961) invested still life with fresh ideas about gender, ambition and artistic personhood, and did so through making simple changes to art historical tradition and to contemporary examples of the genre, and this is particularly clear in a painting she made after encountering Still Life with Apples by Paul Cézanne.

'What can six apples not be?' her sister, Virginia Woolf, asked on first encountering the painting. Bell's response to a similar sense of the still life's possibility was to paint her own version, placing the apples explicitly in her own home.

While Cézanne's fruit float against a backdrop of opaque colour, Bell's are arranged on a patterned china plate, sweet and uneven and shining, fragments of the surrounding interior pushing in from all sides of the frame. The adjustments were subtle, but in making them Bell was asking new questions about the relationship between genre, gender, domesticity and work, and was proposing how aesthetics might absorb the ephemeral idiom of the everyday.

Dora Carrington

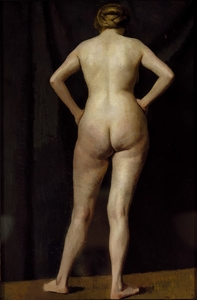

Unlike others, the Slade-trained artist Dora Carrington (1893–1932) turned to still life later in her career, and for reasons that reflect on the conditions necessary for work in the genre.

Painting of Tulips in a Staffordshire Jug

c.1921, oil on canvas by Dora Carrington (1893–1932)

The absence of still life was an emphatic statement on Carrington's limited options in the years after she graduated from the Slade – a time when she was forever looking for rooms and steady employment. This uncertainty was made worse by the losses and fears prompted by the First World War.

Still life was an unnecessary reminder of everything Carrington desperately wanted, but which none of her achievements brought her closer to: a room of her own.

The prominence of the nudes within her early work stresses how in those uncertain years all Carrington really had, her only resource and only comfort, was a self.

By uniting these experiments in still life, a central premise of my book, This Dark Country, was a preoccupation with intimacy: how it felt, what it meant, where it flourished or faltered, how it shifted through queer embodiment and ran aground through the strictures of heteronormativity. The book reveals how an overlooked art form might produce and accommodate richly ambivalent experiences.

Rebecca Birrell, author of This Dark Country: Women Artists, Still Life and Intimacy in the Early Twentieth Century