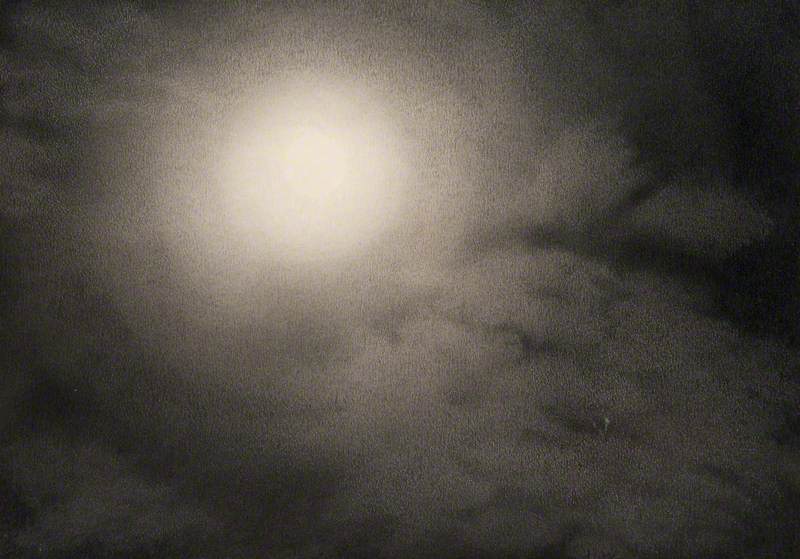

For the traveller on the A836 road on the Scottish mainland's north coast, heading from either east or west, the approach to Borgie Glen is a noticeable yet gentle climb. From the west, across the River Borgie, the incline rises to reveal a view across the glen to Cnoc an Arbhair on the right.

Approaching from the east, where the road narrows, the rolling nub of Cnoc an Fhreiceadain above Coldbackie comes into view, and on the horizon are seen the weathered spires of Ben Loyal and the distant arcs of Ben Hope. Mention of the location is important, as will soon become apparent. Indeed, Edinburgh-born sculptor Kenny Hunter spent over a year travelling to these parts, extensively scoping out the region for a suitable location to site his work.

Regardless of the direction of travel, above Borgie Glen on the A836, signs erected at the roadside by Forestry Commission Scotland (now Forestry and Land Scotland) soon come into view.

They direct the traveller down a track into the glen with two unlikely words enigmatically pointing to The Unknown – which, for initiates in these parts, is actually a well-known public sculpture by Hunter, who is otherwise celebrated for his monumental civic projects.

The Unknown (2012) is something quite other, however – something special, curious and fascinatingly at one with its surroundings in this ancient landscape within which rich folkloric traditions have been kept alive by an oral storytelling culture.

The sign to 'The Unknown'

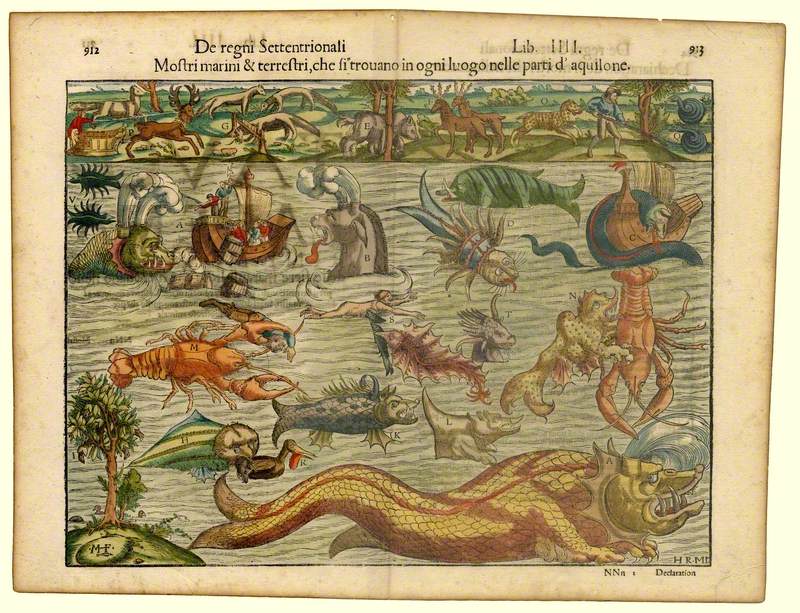

'Throughout the world, there are many stories of monsters and giants. Generally, they are "outcasts" condemned to exist in remote or barren places,' states the publication produced for the unveiling of Hunter's sculpture in 2012.

As it continues: 'Scotland has an empathy with this tradition; as much of its history has been defined by characters and events marked by sacrifice and exile, such as William Wallace, Bonnie Prince Charlie and the Highland Clearances.'

Hunter's work here references these and other sources from both ancient and relatively recent times, situated as it is within an area that contains the remains of settlements from the most infamous and traumatic clearances in Scottish history, as well as numerous Neolithic chambered cairns, Bronze Age forts, roundhouses and Iron Age brochs.

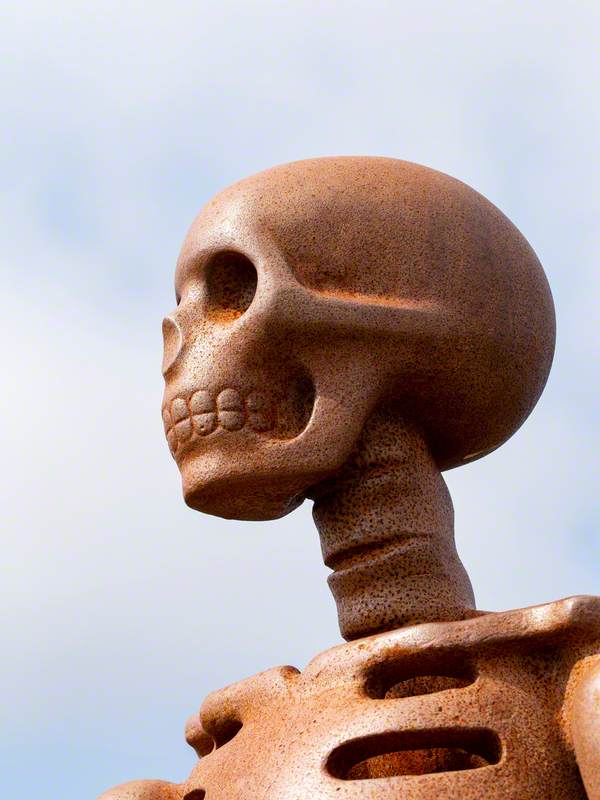

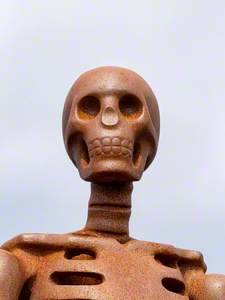

On the first encounter, Kenny Hunter's The Unknown (accessed via a climbing path from the end of the track down into the glen) might surprise. Still, the skeletal form cast at Hargreaves Foundry in the Calder Valley, West Yorkshire, is certainly not out of place. As Hargreaves Foundry itself has referred to The Unknown in the literature relating to their casting of it, 'this is a major landscape work where the journey to it and the rich history of the wild landscape in which it is set, are essential components.'

The sculptor himself has said: 'The Unknown defies the conventions of public art, being both ambiguous and remote. Yet still reminding us of what is now and what has always been. In a strange way, I would align The Unknown with the tradition of Land Art, where the journey to see the work is part of the experience, and you have to make an effort to see it.'

The path at Borgie Glen leading to 'The Unknown'

The sculpture's situation in what Hunter refers to as a 'commercial forest' is also important, he says, for 'this is a landscape that changes over time'. Like so many of Scotland's forests, at Borgie Glen the landscape is periodically subject to industrial-scale logging operations that can level (or in forestry terms, 'clearfell') some 2,500 hectares in just a couple of months, the darksome interior of large sections of forestry stock quickly becoming a gnarled and blighted landscape more reminiscent of Paul Nash's paintings from the Great War, such as The Mule Track (1918) or The Menin Road (1919).

While today's forestry operations may be the most recent sign of a human impact on the landscape of North West Sutherland, further signs that reach back across thousands of years can be detected, too. In Northern and Western Europe, the Iron Age is broadly understood as beginning in 400 BC, eventually giving way to the Bronze Age around 800 AD. In Great Britain, the Iron Age is dated more explicitly from 800 BC to 100 AD, and this, too, is important. Hunter's The Unknown is made of iron, after all.

'The choice to use iron was quite deliberate, and it relates to the Iron Age settlements. It is also a more humble, fundamental metal that is literally in the land,' says the artist. Remembering the work's unveiling, he recalls that, having been made in grey cast iron, at the end of the event came rain. The work quickly began to show the first signs of oxidisation, developing a yellowy ochre patina. Over time, that patina has deepened and now changes with the seasons and the weather.

The sculpture presented Hargreaves Foundry with some significant challenges. More than 30 separate pieces made up the finished mould for the work, and the shape and depth of the cavity within the rib cage meant creating the core in three pieces.

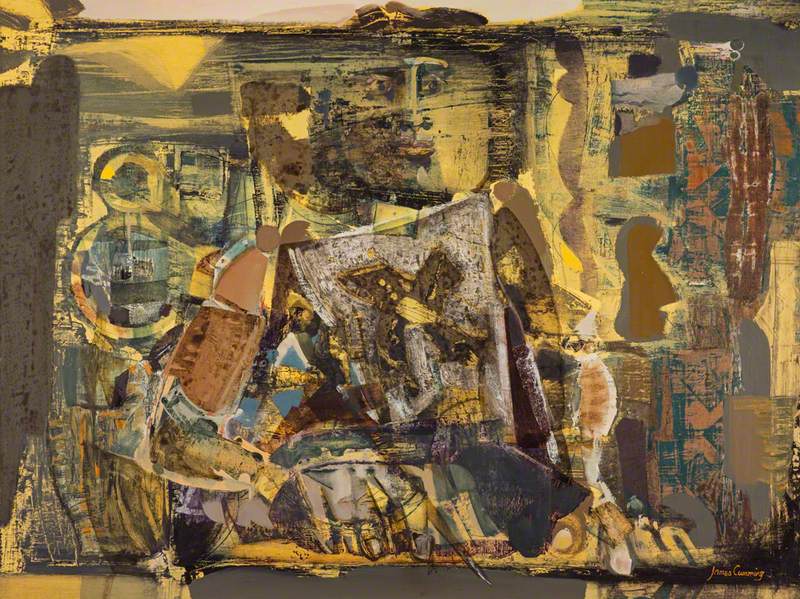

As Hunter describes the making of the work from start to finish, however, it understandably went through several stages, from conception to the physical object that now stands 2.6 metres tall on the hill.

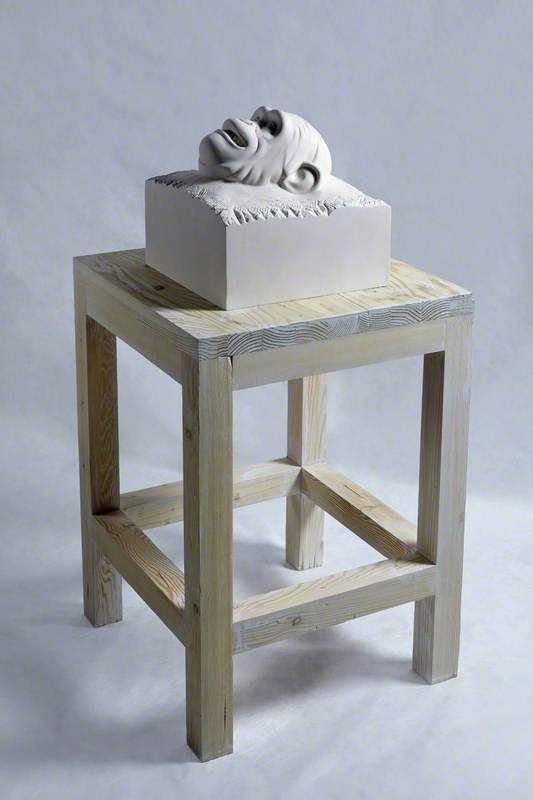

'I made the sculpture in clay,' he explains, 'and then it was cast in polyester resin. From that pattern, the iron cast was made.' Although working on other sculpture projects simultaneously and frequently travelling to the Highlands to identify a suitable location for the work, 'it was probably a three-year period that I was working on it, from conception to completion,' he says.

Developmental work in progress for 'The Unknown'

'One thing I was trying to turn on its head was our expectations of public art,' he continues. 'Not so much contemporary public art, but historical public art, which may have a purpose to serve such as memorialising a particular person or event. The Unknown is more universal because it is a skeleton. The ultimate human image that everyone can identify with.

'There's no gender or race to consider. It is just the basic human armature. A skeleton has an enigma about it, too, but there's the supernatural aspect. A skeleton is usually found lying in the ground, but this one is upright and it looks like it is conscious. It is animated; it has a slight turn of the head and a bent knee as if it is about to stride off.'

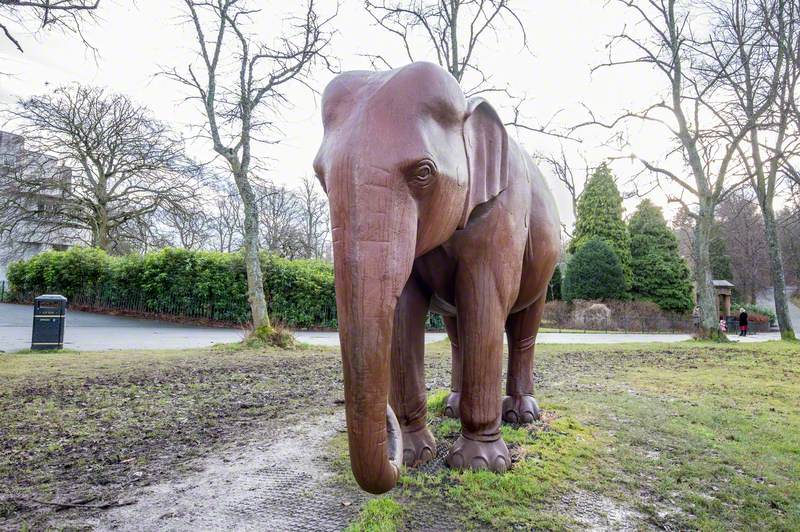

Unlike the many other public art sculptures that Hunter has worked on – many of which feature on Art UK, such as Elephant for Glasgow and The Watcher – The Unknown is unusual for another reason, too. As the artist explains, 'you generally get given a brief with public art. That brief will tell you what the work should address, the timescale, and so on, and then you come up with a design and go into competition.

'For this project, I had to lobby for the work and apply for a grant from Creative Scotland to develop the idea.' At such an early stage of development, what we see today was far from a fixed idea, however, and it went through several stages before Hunter set upon the skeletal form we see today.

'I began by looking at the idea of a Scottish monster; the exile or one who is banished, like William Wallace, Bonnie Prince Charlie, or a Jekyll and Hyde. A kind of Gothic figure. That is how the project started, anyway. It obviously became something else on the journey, but that is often the way with art.'

'Through getting involved with the subject matter and the material, and, of course, the site itself and the people who supported it, once I had developed the skeleton idea and had met the curator of the Strathnaver Museum in Bettyhill and local arts figure Meg Telfer, I was introduced to a lot of people who told me local "giant stories".

'For example, the giants who threw boulders at one another between Skerray and Bettyhill, and so the sculpture became a kind of giant, I suppose, because giants, generally, are "outcasts", too condemned to exist in remote or barren places. Meg Telfer also told me that, historically, locals had been quite big, genetically.

'Many of them ended up serving in Highland regiments. I also looked into the history of the Clearance sites in Strathnaver Glen and what happened there. There's a sense of absence to many sites in the Highlands. Therefore, The Unknown is a human equivalent of that or a fragment of a person standing there, but it has a presence.'

Borgie Glen

As Hunter explains the development of his ideas for the work, he says he was not interested in rendering what he describes as 'an anatomically correct skeleton'. Instead, his thinking was that it should be something that was 'more like a folk art skeleton as if made from memory'.

Expanding on this, he recalls his study of Pictish carvings and rock drawings of salmon, boar or deer, 'which captured the spirit of the animals without being anatomically precise. That's what I was trying to achieve in this very basic, singular reductive form that stood up, large like a giant but not so big that it was an oppressive object.

'The ambiguity of it is very important, too. I like the aspect of the storytelling and myth, as though a new story could emerge in relation to the sculpture, and that I hadn't played a direct part in forming or shaping that story in any way. In fact, I settled on the title The Unknown because I felt that that would help with the ambiguity of the work and the idea that you could develop your own personal meaning for it.'

Additionally, the sculptor observes, 'when archaeologists come across sites, the word "unknown" comes up quite often if an object or a piece of art is of unknown origin.' History can never be understood in its entirety, he maintains. 'We can only know history as fragments. Ultimately, we will always put something subjective together to explain those fragments because all we have are these "bits".'

Like all public art, however, The Unknown is 'a bit like a dripping tap, dripping away into the public consciousness over time, but this sculpture could be there for ages, quietly affecting the psychogeography of North West Sutherland'.

Like the oral tradition as a continuing part of Highland Culture, therefore, The Unknown will change over time in small and often near-imperceptible ways, maybe taking on new and unexpected meaning, albeit having once been a sculpture that was conceived in response to that oral tradition as Hunter encountered it when first beginning his research for the project.

View this post on Instagram

'I'm really quite proud of the project in a way,' says Hunter. 'That's not a word I use a lot, but I am proud because it was really quite hard work getting it into the ground. The Forestry Commission were a good supporter of the work. They helped with building the foundation and transporting it off the lorry and up the hill, which was no small task in itself.

'Then there was the work spent on the administration side of the project, but the making of it was something I really enjoyed, too. One of the things that pleased me most about it, though, was the sign that Forestry Commission Scotland erected at the roadside. I often ask myself what people who are not familiar with the area think when they see that sign on the A836 at Borgie, pointing to The Unknown?'

Ian McKay, writer and editor

This content was supported by Creative Scotland