The Sculpture Placement Group (SPG) is an organisation intent on solving some of the problems facing artists who make sculpture.

The charity, founded by three friends in Glasgow in 2019, is challenging the way people commission, collect and engage with three-dimensional artwork, making it more accessible to the public in a way that is financially sustainable for artists.

The SPG's founders – Martin Craig, Michelle Emery-Barker and Kate V. Robertson – work closely with artists to develop their projects, which are aimed at prolonging the lifespan of sculpture.

The Sculpture Placement Group

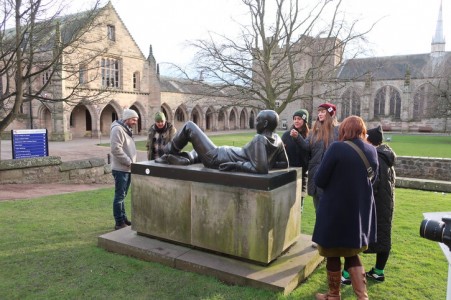

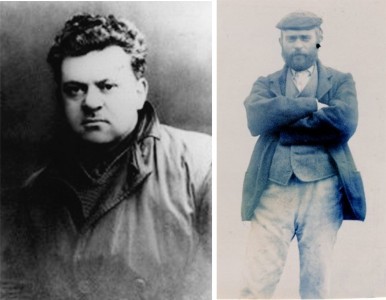

Kate V. Robertson, Michelle Emery-Barker and Martin Craig of the Sculpture Placement Group with one of their first loans, 'The Spirit of Kentigern' by Neil Livingstone

A recent report indicated that sculpture is a discipline in decline, so the SPG are addressing issues such as how three-dimensional work is funded, and what happens to it after it has been exhibited.

Robertson, a practising artist, cites a visit she made early in her career to a field in Budapest, where disused Soviet sculptures were being stored, as a key influence in her interest about what happens to sculpture when it's no longer on display.

Now, Robertson explains, the Sculpture Placement Group has three main aims: 'We want to make improvements to economic conditions for artists, to bring art to new audiences, making it more accessible, and we want to address the waste in commissioning an artwork that gets shown once and then binned.'

Just as Art UK holds a database of work in public collections, much of which is in storage, the SPG's Stored Sculpture Inventory lists sculptures that have been exhibited but are no longer on view. If works are not sold at exhibition, then afterwards they will usually be stored, often at the expense of the artist.

Each day we're going to be highlighting a sculpture that's part of our online inventory. Today's #sculptureinventory is @Tessa_J_Lynch - Celebratory Nap (2017), currently in storage in her studio at @GSSGLASGOW https://t.co/96hEkPd9cM pic.twitter.com/dl40j8I6W9

— Sculpture Placement Group (@SculpturePG) April 30, 2020

The inventory makes that artwork – listed on the SPG's website as being in locations from studios to sheds to 'the artist's ex-boyfriend's attic' – visible to the public, curators and researchers, as well as potential purchasers. The artists listed on the site range from recent graduates to established practitioners such as Toby Paterson and Graham Fagen.

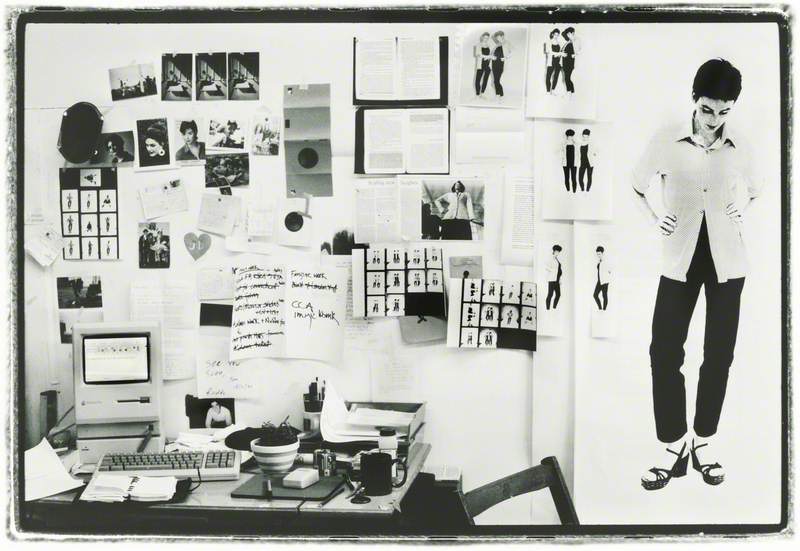

One of the first projects the three friends ran together before establishing the SPG was the 2014 exhibition 'Reclaimed: The Second Life of Sculpture'. The show in Glasgow brought a large number of sculptural works out of storage, including artworks from both private and public collections, some of which had not been seen by the public in over two decades.

The 2014 exhibition 'Reclaimed: The Second Life of Sculpture'

Their 'SPG Loan' scheme places sculptures that are in long-term storage with guardian organisations, communities and businesses, creating a new model for artwork to be seen by more diverse audiences, while also alleviating the problem of storage. So far, sculptures have been 'adopted' and placed in locations including hospitals, council offices and shopping centres.

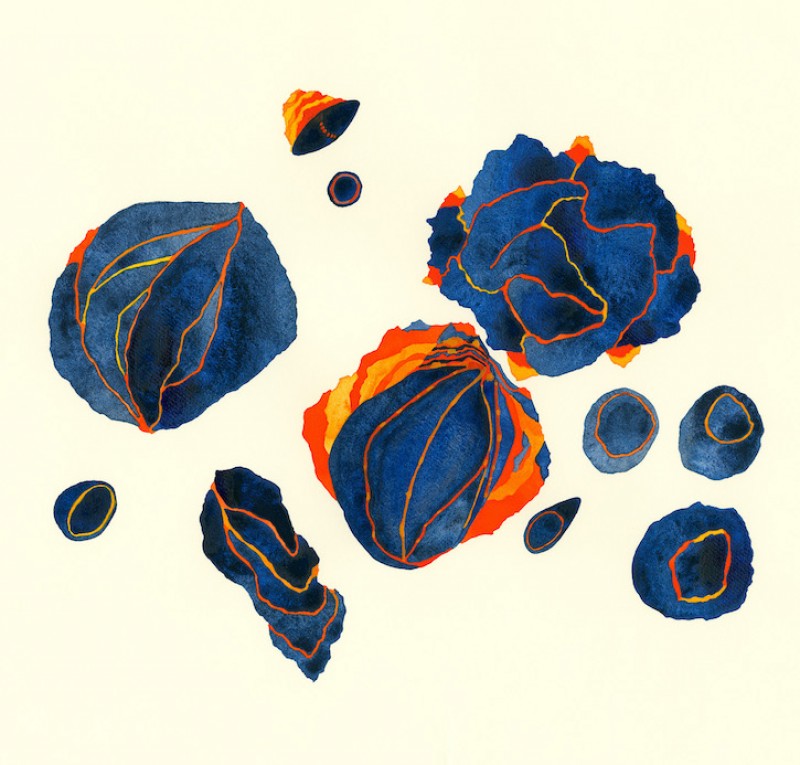

Fragments

2017, cement, marble & pigment by Andrew Lacon. 'Adopted' through the SPG by Hidden Gardens, Glasgow

The SPG is in regular discussion with artists about how they hope to develop their practices, and with collectors about what sort of sculpture they're hoping to acquire, enabling the organisation to act as matchmakers.

Earlier in 2021, the group trialled a new model of commissioning sculpture, developing an acquisition partnership that allowed Glasgow-based artist Jacqueline Donachie to make STEP for the city's biennial festival, Glasgow International.

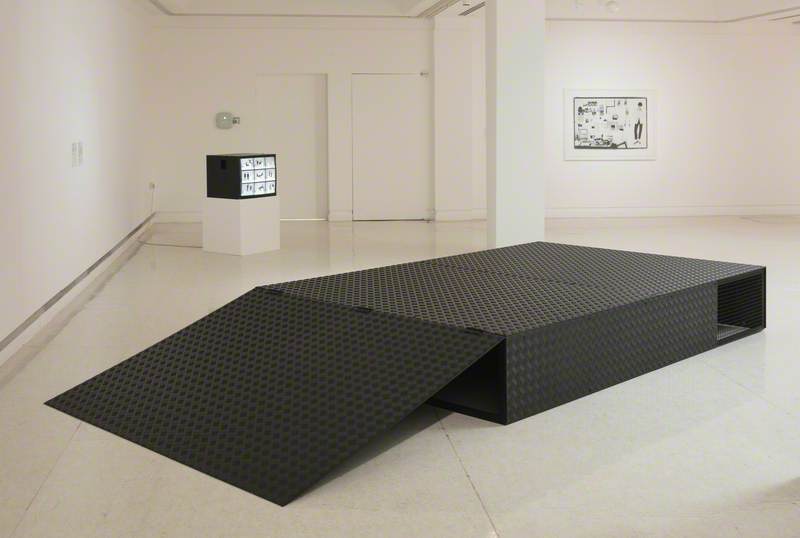

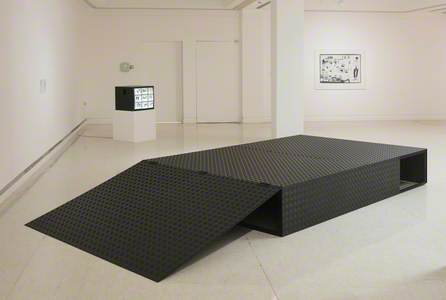

STEP

2021, cast concrete by Jacqueline Donachie

It is an ambitious cast concrete outdoor work that involved little of the financial risk usually associated with making large-scale sculpture.

The project was part of a partnership with SWG3, a multi-disciplinary arts venue and events company in Glasgow, with additional support from Creative Scotland and Glasgow City Heritage Trust.

STEP

2021, cast concrete by Jacqueline Donachie

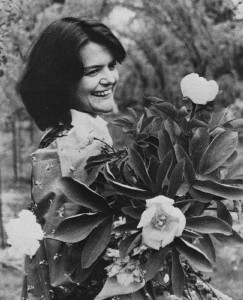

Donachie is known for her socially engaged art practice that explores identities and the structures and spaces that support them. Her work often looks at how people navigate space, what connects and separates people, as well as accessibility for people with disabilities – something particularly relevant to her as several members of her family have muscular dystrophy.

STEP is a series of modular blocks that can be temporarily assembled to make a ramp that doubles as civic architecture, encouraging resting, socialising and play.

For the duration of the festival, STEP was temporarily located at Govan Graving Docks, which closed in the 1980s, marking the end of Glasgow's role as a key trading centre and the end of large-scale industrial manufacturing in the city.

STEP

2021, cast concrete by Jacqueline Donachie

Among the old cobbled quays, complete with access ramps, hulking bollards and rusting winches that provide a home to wildlife, STEP provided a public space for reflection and contemplation overlooking the Clyde.

After two weeks, it was relocated to its permanent home at SWG3, who will now look after the work, and use it as modular outdoor seating.

STEP being moved to its new location

2021, cast concrete by Jacqueline Donachie

As a maker of large-scale sculptures and installations, Donachie gives careful consideration to the afterlife of artworks.

'If you want to make work, you have to be very careful what you're left with', she says. 'I know a lot of artists who spend all their money paying storage for artworks that might never get seen again.'

Jacqueline recycles and repurposes materials wherever she can, and cites the artist Phyllida Barlow, and her pragmatic re-use of materials, as inspiration.

Donachie often remakes any high-value and durable materials into new sculptures, such as the materials she used in New Weather Coming, 2014, a series of itinerant sculptures that travelled holiday routes around Scotland, being displayed in locations that facilitated arrival or departure, such as railway stations.

Aluminium sheet from this project was later repurposed. Sometimes, after works are exhibited, they are weighed in, and Donachie reclaims the scrap-metal value. For her, this is a functional necessity in a world where waste is being generated at incalculable cost.

If she finds it's not possible to recycle or store a large-scale piece of sculpture, she finds solutions to make it viable, such as hiring scaffolding that can be returned when the project is over.

The partnership with SWG3 that supported the production of STEP was unusual in that it provided an additional budget for Jacqueline to work in cast concrete, opening up a whole range of tactile possibilities in the finished work, which includes pigmented concrete and metal chequer plate textures embedded as part of the casting process.

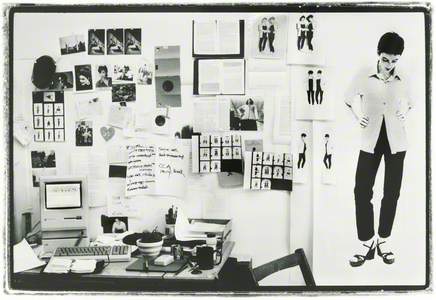

STEP at Govan Project Space

An exhibition of work by Jacqueline Donachie that ran concurrently with her STEP sculpture in Govan

For Robertson, the emphasis that is placed on commissioning new work often suits the agenda of a curator or gallery, but can leave the artist with material burdens that are difficult to manage.

However, she believes that things could be different if more thoughtful commissioning considered problems of sustainability and legacy as part of production.

One of the issues with public sculpture can be the gap between what is temporary and what is permanent. Jacqueline describes herself as a big fan of public art, with the caveat that 'you can get a bit of a build-up of things that just deteriorate and need to be removed – but nobody takes the responsibility to do that.'

Being respectful of where the work is being sited is very important to her, and the acquisition partnership brokered by the SPG has facilitated public access to the piece in a temporary location, while securing a long-term home afterwards where it will be cared for and maintained.

Donachie studied Environmental Art at Glasgow School of Art, and has long been drawn to public spaces where bodies rest, wait and transition: streets, bus stops and bus shelters.

'If I look back a long time in my work, I think I was using and drawing handrails, ramps and railings even before my whole family were diagnosed with muscular dystrophy,' she says. 'It's a weird coincidence.'

For STEP, she set out to survey a range of heritage architecture used as arts venues across Glasgow and, working with an architect friend, constructed schematic drawings of imaginary ramps as a way of highlighting access barriers that often go unnoticed or ignored.

STEP at Govan Project Space

An exhibition of work by Jacqueline Donachie that ran concurrently with her STEP sculpture in Govan

For her, the ramp is a motif for disability and access as well as a means of drawing attention to architectural elements that are often overlooked, but she emphasises that the works are as much about care and carers as they are about disability.

Some of her earlier ramp sculptures, such as Deep in the Heart of your Brain is a Lever, pivot on a hinge, hinting at the ominous possibility they could slam shut on you.

Access is a theme that runs concurrently through both Donachie's work and the SPG's aims and objectives. Robertson and her colleagues champion the principle of sculpture being made accessible to people by orchestrating situations where they can encounter artworks as part of everyday life.

This radically undermines principles of exclusivity so carefully fostered by the art market. The questions raised by the SPG are not always welcome in a commercial sector anxious not to undermine the market value of its artists, but they are key to the survival of sculpture as a discipline increasingly constrained by economic parameters.

While there is much to address, the problems and challenges that are specific to sculpture go hand in hand with its unique possibilities for engagement.

Jessica Ramm, artist and writer

This content was supported by Creative Scotland