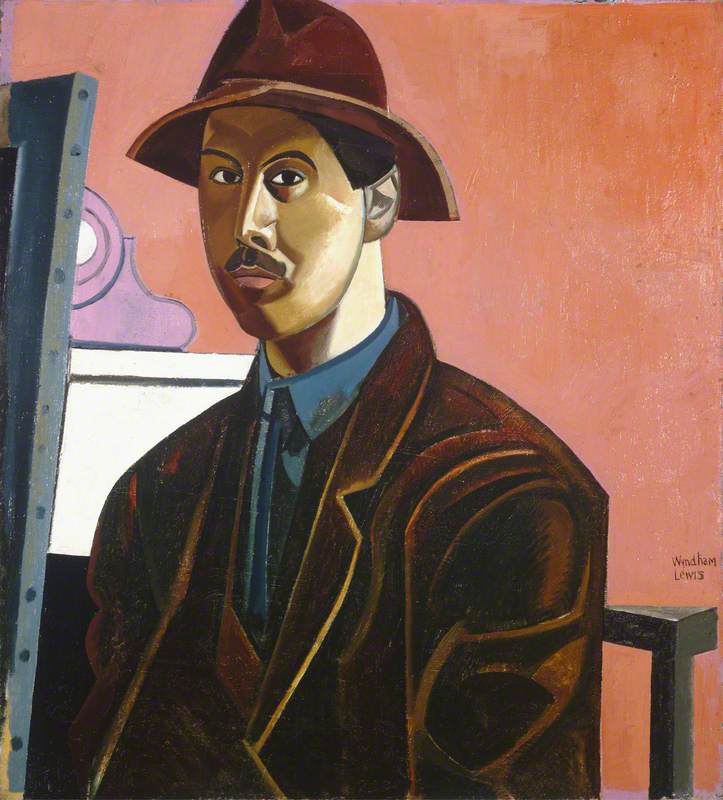

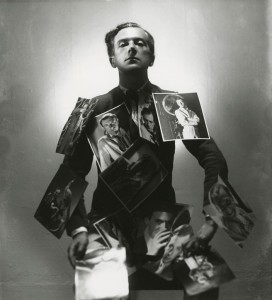

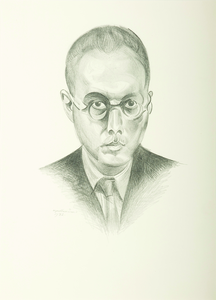

'[Lewis] was always on a war footing; he believed others were likewise disposed... War played, I think, a considerable part in his imaginative life: he occasionally used military terms to describe his own operations, offensive or defensive, and he alluded more than once to his belonging by birth "to a military caste".' – John Rothenstein, Brave Day, Hideous Night (1966)

The words of John Rothenstein, one-time director of the Tate and long-term Lewis champion, capture the common view of an aggressive, antagonistic and bellicose Wyndham Lewis.

The reality was, of course, more complex – this most independent of thinkers was prone to wilful contradiction and deliberate provocation. It is without doubt though that Lewis's life, attitudes and art were impacted by the most violent and chaotic period in recent human history; an era that encompassed two world wars, the Bolshevik revolution, the rise of Stalin and fascism, the Spanish Civil War, the Nazi Holocaust and the emergent nuclear age.

His works were suffused with the key doctrines and philosophies of the modern epoch, from Bergsonian and Nietzschean 'process philosophy' to the existential angst of the post-1945 era. Lewis's own critical writing, acerbic satire and social commentary were notorious, assailing not only the cream of British literary society but also major figures of the day, from Chaplin to Hitler.

The shadow of war was present from the very beginning. Lewis's errant father was a former US cavalry officer and Civil War veteran – hence the talk of 'a military caste'. Lewis subsequently grew up in a Britain riven with political, class and generational discord; a situation played out across all of Europe's major powers, edging each towards internecine conflict in 1914.

By founding the avant-garde Vorticist group and its polemical literary magazine BLAST in June 1914, Lewis was a high-profile embodiment of the restless iconoclasm of Britain's educated youth on the eve of the First World War. Indeed, for the likes of D. H. Lawrence and C. R. W. Nevinson, the war offered a harsh tonic for a moribund society.

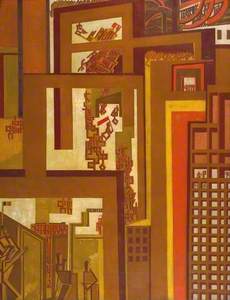

For his part, Lewis rejected the notion of a 'regenerative war' and regarded the First World War as the terrible, but logical, outcome of the philosopher Henri Bergson's notion of 'creative evolution'. This urged humans to embrace a universal 'life force' and submit to the impulses of the animal kingdom. Drawings such as the 1914 Combat No. 2, therefore, offer an image of humanity reduced to mechanical urges to either fight or mate.

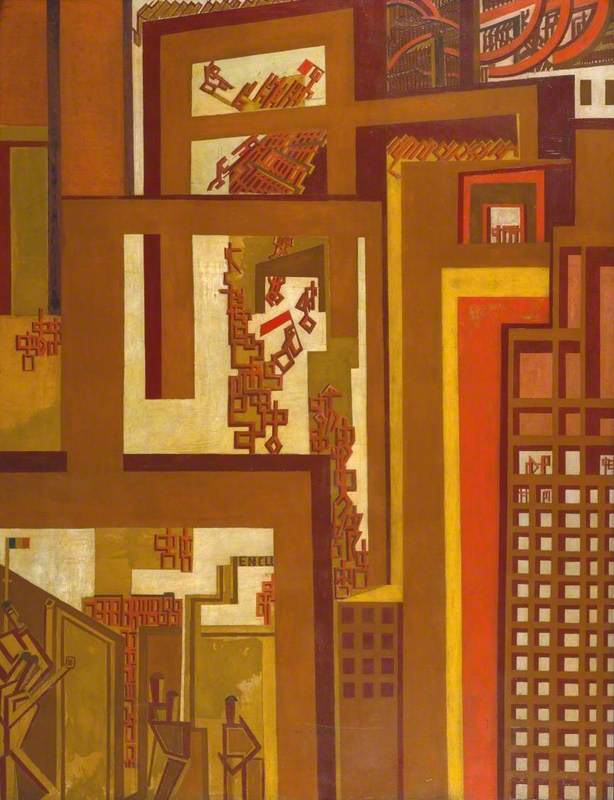

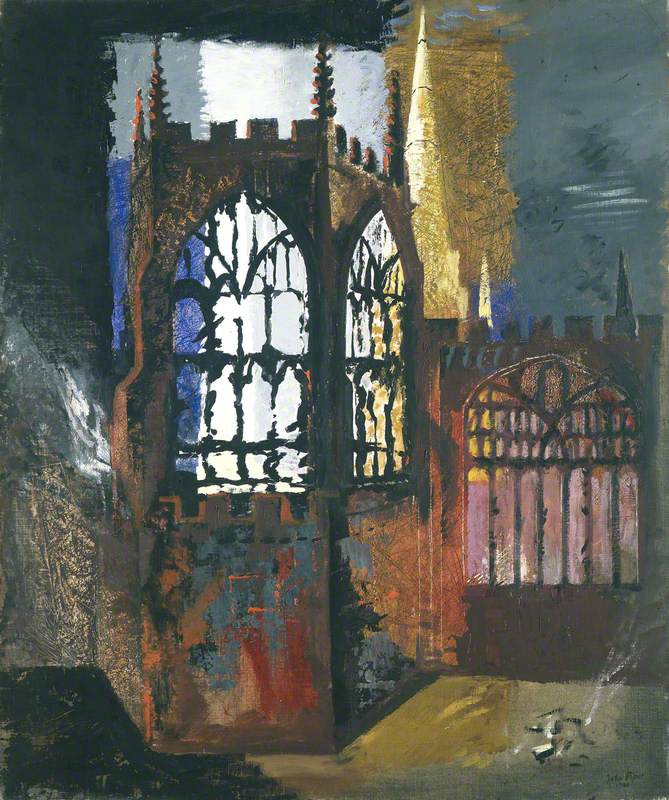

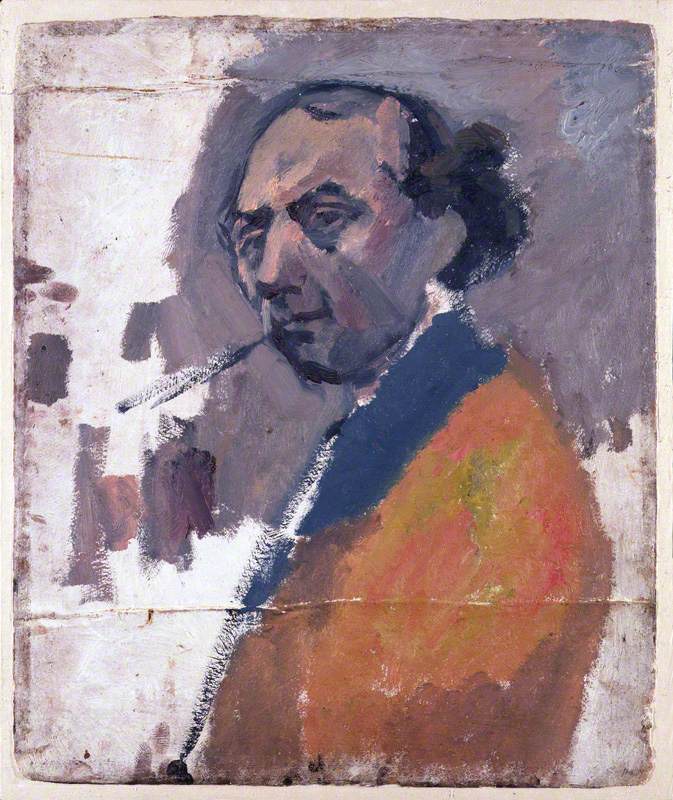

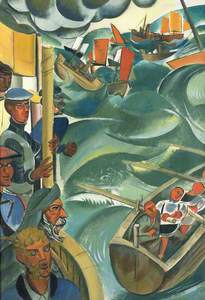

The First World War was the nemesis of Vorticism, its followers scattered by service or killed in the fighting. Lewis himself underwent a hiatus from artistic activity while serving as a subaltern with the 330th Siege Battery of the Royal Garrison Artillery. The art he subsequently created, both privately and as an official war artist for the Canadians and the British from 1917, was much changed from his Vorticist abstraction.

He insisted that the stylised figuration adopted in his drawings was 'a direct, ready formula to give interpretation to what I took part in in France', motivated by a desire 'to do with a pencil and brush what story-tellers like Tchekov or Stendahl did in their books'. However, saying also that he had 'abandoned those vexing diagrams by which he puzzled and annoyed' meant no return to Vorticism, but instead a greater regard for subject matter and narrative, culminating in a wartime magnum opus, A Battery Shelled.

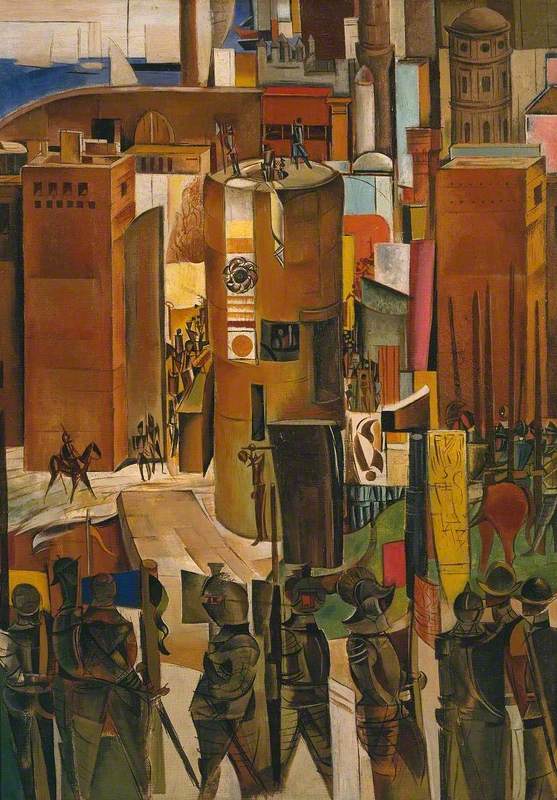

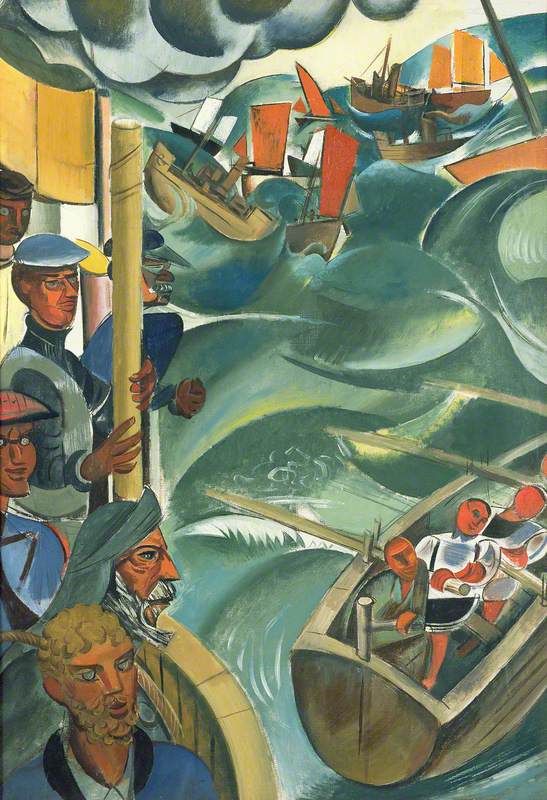

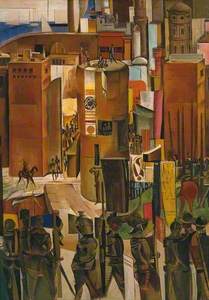

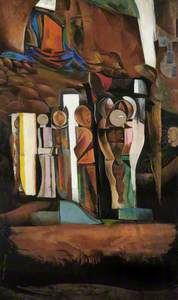

A Battery Shelled fulfilled an ambition to synthesise modernist sensibility with the grand tradition of history painting. Lewis achieved this feat again 18 years later with his impressive The Surrender of Barcelona, a partial homage to Diego Velázquez's The Surrender of Breda (1634–1635). Begun in 1936, almost 300 years after the Velázquez masterpiece, its production coincided with the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War – though Lewis was guarded about any immediate association with the conflict.

As with all Lewis's historical subjects of the 1930s, it concerned violent conquest, and seemed to reflect and anticipate current and future conflicts. Coinciding with this was the publication of Blasting and Bombardiering (1937), Lewis's timely autobiography of his career prior to and during the First World War. Besides detailing his exuberant pre-war years and the ensuing disillusionment of the war, the spectre of future conflict loomed large over its pages, with Lewis – the veteran – cautioning: 'There is for me no good war and bad war. There is only bad war.'

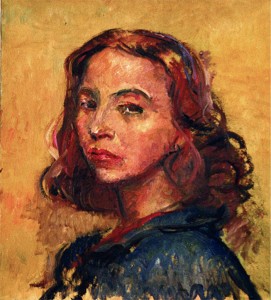

Lewis's resentment towards the First World War was acute and ingrained; it robbed him of his friend Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, denied him his most productive years and, most painfully, took his beloved mother. The strain of war, Lewis was convinced, caused her premature death in 1920. His own experiences serving at Messines Ridge and Passchendaele in 1917 would colour his subsequent outlook and expectations, and the 'deliberately invented scenes' of the Western Front would inspire some of his most compelling and disturbing art and literature.

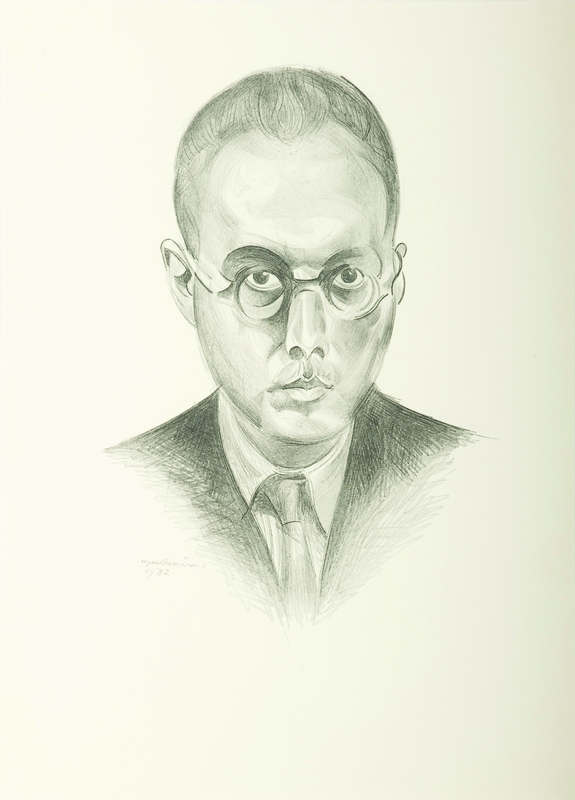

In the 1930s, an individual crusade to prevent future war saw Lewis embark on a period of political writing, the ill-judged conclusions of which would have dire personal consequences. Already preferring authoritarian power over democracy (disdained as rule by the 'herd'), a chief concern of Lewis was the perceived 'left-wing orthodoxy' of a blinkered British cultural elite.

Virulent anti-communism blinded him to the evils of fascism. In 1931, his infamous essay Hitler portrayed the Nazi leader as a 'man of peace' and a barrier to Soviet incursion in Europe. Lewis backed his position five years later in Left Wings Over Europe, urging appeasement of Hitler and Mussolini and dismissing, like many others, warnings to the contrary from Winston Churchill as war-mongering. Similarly, in Count Your Dead – They Are Alive!, Lewis excused the actions of General Franco in the Spanish Civil War as necessary to resist communism.

Too late then was Lewis's trip to Nazi Germany in 1937, which exposed the true nature of the regime. Hastily recanting his earlier pronouncements, he published The Jews: Are they Human?, a sincere but ham-fisted denouncement of antisemitism, and The Hitler Cult and How it Will End (1939). In this, Lewis derided the Führer as a deluded romantic confronted by realities he could not understand.

Yet the damage was done. For Lewis's detractors, his association with Nazism was unforgivable, and his reputation has never recovered. He faced further criticism for his apparent desertion of Britain for Canada at the outbreak of the Second World War. Intended as a fresh start abroad after the controversial rejection of his portrait of T. S. Eliot by the Royal Academy in 1938, Lewis found life in the 'stony desert' of New York and 'sanctimonious icebox' of Toronto no more conducive.

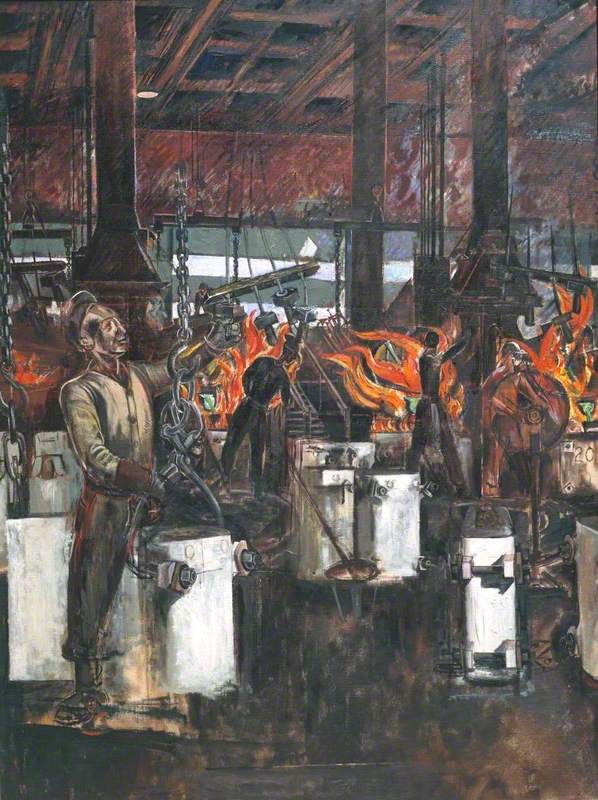

In poor health and facing destitution, he was cast a lifeline in 1943 by Britain's official war art scheme. However, Lewis's commissioned painting, A Canadian War Factory, proved problematic. Afflicted with self-doubt and indecision, he changed his approach twice, so that by his return to Britain in August 1945 it was still unfinished.

Lewis returned to a country exhausted by war and in the grip of austerity, a state of affairs he powerfully evoked in his collection of literary sketches, Rotting Hill. Despite approaching blindness, this final period of Lewis's life was perhaps his most stable.

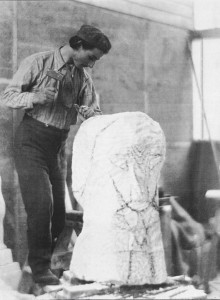

As art critic for the BBC's cultural weekly, the Listener, he championed a new generation of British artists, including Francis Bacon, Michael Ayrton, Barbara Hepworth and John Minton, and even advocated state-subsidised arts on a par with the newly formed National Health Service.

In 1951, the BBC commissioned Lewis to complete his Dantesque afterlife trilogy, The Human Age, initially begun in 1928 with The Childermass. The three volumes conjured a nightmare fantasy world of corporate consumption, compliant masses and a hell operated by a dapper devil, Sammael.

Lewis's hellish imagery was undoubtedly derived from his experience of the Western Front and later by images of the Nazi concentration camps – though, as a whole, The Human Age was a response to the Cold War and the capitalism of the post-war era, which the author believed would lead inevitably to a future nuclear world war.

Thankfully, this is a prediction from this most astute of modern minds that has until now proven wrong.

Richard Slocombe, Art Curator, IWM (Imperial War Museums)

This article is based on an edited extract from Wyndham Lewis: Life, Art, War published to accompany the exhibition at IWM North from 23rd June 2017 to 1st January 2018.