An unmatched social climber in seventeenth-century England, George Villiers (1592–1628) rose rapidly to become one of the most powerful men in the kingdom. He achieved this through his role as King James VI and I's 'favourite', a position that blended personal intimacy with political clout.

George Villiers (1592–1628), 1st Duke of Buckingham

17th C

Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640)

Recently dramatised in the Sky TV series Mary & George starring Julianne Moore and Nicholas Galitzine, Villiers lived a fascinating and tumultuous life. Alongside his extraordinarily influential career in English and international politics, he was also a great patron of the arts, carefully crafting his public image through portraiture and allegorical paintings.

The second son of a minor nobleman, Villiers grew up in relative obscurity. But thanks to a combination of charisma, good looks and ambitious politicking, he quickly inveigled himself into King James' court.

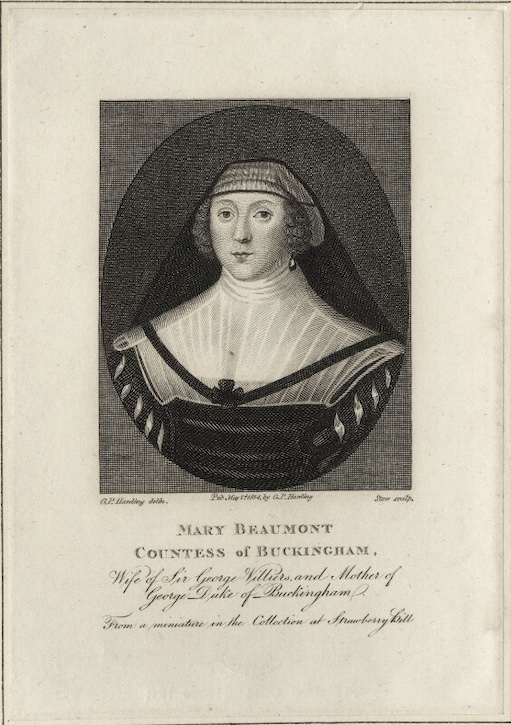

As the title Mary & George suggests, Villiers' mother Mary played a crucial part in his rise to power, making sure he received the appropriate education to become a successful courtier.

Historians characterise her as a cunning strategist who made plenty of enemies as she and her son gained more influence over the king.

James I (James VI of Scotland) (1566–1625), in Garter Robes

c.1625/1645

Daniel Mytens (c.1590–1647) (after)

Becoming the king's favourite

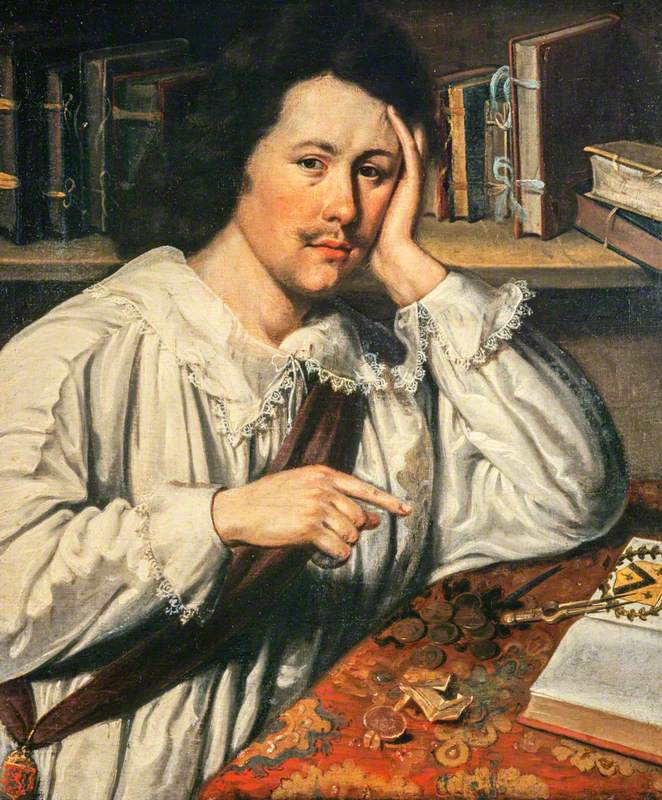

After meeting the king in 1614, Villiers captured his attention through skilful dancing and personal charm. An early court portrait depicts him as a sumptuously dressed young gentleman with chin-length dark hair and a slim build.

George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham

c.1616

William Larkin (c.1585–1619) (attributed to)

The accessory on Villiers' left leg advertises his position as a Knight of the Garter, a senior member of the court. Not shy about promoting his favourites, by 1616 the king had already made Villiers a viscount and given him two important jobs: Master of the Horse and Gentleman of the Bedchamber, an official title for trusted members of the king's inner circle which allowed full access to the king as he dressed and ate.

Some historians assume that James and Villiers were lovers, with Villiers' biographer Benjamin Woolley saying that they exchanged love letters displaying 'a very deep, complex, probably sexual relationship'.

George Villiers (1592–1628), 1st Duke of Buckingham

1619

Cornelius Johnson (1593–1661)

James and George's burgeoning relationship wasn't a secret affair. The king was known for lavishing attention on young male favourites, highlighting the difference between seventeenth- and twenty-first-century conceptions of marriage and sexuality. Identity categories such as 'gay', 'straight' or even 'closeted' didn't exist in the way we understand them today. It was also pretty normal for kings to have publicly acknowledged lovers in addition to their arranged, political marriages.

In a system structured around nepotism, the king's favourites exerted astonishing levels of influence. For instance, James' previous favourite Robert Carr was quickly knighted, then made 1st Earl of Somerset, and elevated to key positions in the government.

Robert Carr, Earl of Somerset

(copy after an original of c.1625–1630)

John I Hoskins (c.1590–1665) (copy after)

However Carr's days were numbered. His enemies helped Villiers gain more prominence in court, giving the charming newcomer ample opportunities to depose Carr in the king's affections.

A patron of the arts

Now rich and well connected, Villiers commissioned numerous theatrical masques and paintings throughout his time as the king's favourite, employing leading artists such as Flemish painter Peter Paul Rubens. One of the most intriguing examples refers to his 1620 marriage to the aristocrat Katherine Manners; a wedding with an awkward origin story.

Katherine Manners (c.1603–1649)

c.1633

Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641) (copy of)

Portraits show Katherine as a woman with an oval face, a prominent nose and curly dark blonde hair. We know this particular image was painted after her husband's death because she is dressed in mourning black and wears a cameo painting of Villiers around her neck.

King James literally referred to himself as Villiers' husband in private letters ('god bless you, my sweet child and wife...'), but that didn't preclude official marriages and the expectation to produce heirs. The king was already married to Anne of Denmark, and Mary Villiers saw Katherine Manners as an appropriate choice for George.

There was only one problem: Katherine was Catholic. She converted to Protestantism to appease Villiers' religious affiliations, but her father wasn't impressed. He only agreed to the marriage following a messy set of circumstances, after accusing George of ruining Katherine's honour.

After accepting an invitation to visit Mary Villiers, Katherine ended up staying the night due to a sudden and unexpected bout of illness. Since George stayed over in the same house that night, Katherine's father assumed that she'd slept with him – scandalous for an unmarried woman.

But by making this accusation publicly, the Earl played himself into a corner. His daughter now had to marry a suitor he'd previously opposed. The resulting wedding inspired a rather pointed artistic commission from Villiers. (Unsurprisingly, there's some speculation that Mary Villiers engineered this entire situation to make sure the marriage went ahead.)

Painted in 1621, Anthony van Dyck's The Continence of Scipio depicts a scene with the Roman general Scipio, thought to be modelled on Villiers himself.

After conquering the capital city of Spain, Scipio was supposedly 'given' a beautiful local woman. Discovering she was already engaged, he returned her to her family unscathed. So this painting shows Scipio (i.e. Villiers) demonstrating his honour by respecting a woman's chastity.

It also doubles as a reference to Villiers' military role as Lord High Admiral – a recent promotion the king celebrated by writing poetry comparing Villiers to the sea god Neptune.

Double portrait of George Villiers and his wife Katherine Manners

George Villiers, Marquess and later 1st Duke of Buckingham (1592–1628) and his wife, Katherine Manners (1603–1649), as Venus and Adonis, 1620–1621, oil on canvas by Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641), private collection

Another Van Dyck commission went in a very different direction, portraying George and Katherine as a semi-nude Venus and Adonis, sending an overtly romantic and heterosexual message about their marriage.

The Duke of Buckingham and his Family

(copy after an original of 1628)

Gerrit van Honthorst (c.1590–1592–1656) (copy after)

Adding to Villiers' slew of titles, the king raised him even higher in 1623, creating him Duke of Buckingham. This confirmed a unique level of power alongside James' heir, the future king Charles I. By comparison, James' predecessor Elizabeth I never created a new duke.

Portraits from this period depict Villiers as a poised gentleman with a fashionable moustache and goatee, sometimes emphasising his military duties. This portrait by Daniel Mytens portrays him wearing armour with a fleet of ships in the background.

George Villiers (1592–1628), 1st Duke of Buckingham

Daniel Mytens (c.1590–1647)

The reign of Charles I

Bucking the expected trajectory for a royal favourite, Villiers hung onto power after James' death in 1625. This was primarily due to his established friendship with the new king, Charles I.

Charles' loyalty was crucial during Villiers' later years, which were beset by a series of high-profile political and military failures. Villiers was increasingly reviled by the public, facing government opposition alongside scurrilous commentary in popular culture.

Art as propaganda

James' reign inspired a wave of plays and poems about royal favourites, often relying on classical Greek or Roman allegory. Avoiding direct references to the king or Villiers, an author might pen a tale about Sejanus (a close friend to the Roman emperor Tiberius) or Crispinus (the favourite of the emperor Nero).

Even less flattering was the subgenre of political poetry known as 'Stuart Libel', referring to the king's family name of Stuart. Some poems accused Villiers of corruption or straightforwardly mocked his relationship with the king.

One salacious verse joked that Villiers 'sate downe a viscount, and rose upp an Earle', promoted absurdly fast due to his handsome face and talent for dancing. When Villiers commissioned portraits of himself as a glorious statesman, he may have been pushing back against this kind of attitude.

Minerva and Mercury conduct the Duke of Buckingham to the Temple of Virtue

before 1625

Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640)

The Rubens sketch pictured above is a notable example, labelled The Apotheosis of the Duke of Buckingham (apotheosis being the process of deification, casting Villiers as a godlike figure). Depicted in quasi-Roman garb, Villiers is the character in the middle, being carried aloft by gods such as Minerva (wisdom) and Mercury (the messenger). They're taking him toward the Temple of Virtue in the top left corner.

It's an undeniably self-aggrandising image, but as the National Portrait Gallery's own description points out, this elevation of status 'is not a wholly majestic and dignified affair'. Villiers' ascension takes place in the midst of a crowded and chaotic scene, and a figure representing Envy is literally trying to drag him down by the feet. He commissioned this allegorical painting for a ceiling in his London house (now destroyed by fire), so it was clearly an image he wanted his family and guests to see on a regular basis.

A scandalous end

Villiers' death came suddenly, at the end of a knife. At the age of 36, he was stabbed at a public inn, assassinated by a disaffected army officer named John Felton.

Apollo and Diana

1628, oil on canvas by Gerrit von Honthorst (1590–1656)

Villiers' final artistic commission arrived shortly after his death: an ambitious allegorical painting by Gerrit van Honthorst from 1628, depicting the Olympian gods Apollo and Diana surrounded by figures embodying 'Liberal Arts' such as music and rhetoric. Apollo represents Charles I, while Villiers appears as Mercury, positioned centrally – at the heart of monarchy – as a leader of the arts and paying homage to Charles and his queen, Henrietta Maria.

Gavia Baker-Whitelaw, film critic and culture journalist

This content was funded by the Samuel H. Kress Foundation

Further reading

Alastair Bellany, 'Singing Libel in Early Stuart England: The Case of the Staines Fiddlers, 1627', Huntington Library Quarterly, 2006

Elinor Evans, 'Who was George Villiers, favourite of King James VI and I?', History Extra, 5th March 2024

Pamela Gordon, 'The Duke of Buckingham and Van Dyck's "Continence of Scipio"', Canadian Art Review, 1983

Siobhan C. Keenan, 'Staging Roman History, Stuart Politics, and the Duke of Buckingham: The Example of "The Emperor's Favourite"', Early Theatre: A Journal Associated with the Records of Early English Drama, 2011

Apollo and Diana, Royal Collection Trust notes

'Favourites: Art and Power, 1600–1800', past exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery, London, 18th July 2014–26th July 2015