As a deadly virus spreads across the country, parallels can be drawn with the experience of the nation living through the First World War, generations ago. Rationing of essential supplies was enforced on a nation in lockdown, which tuned in at 5pm every day to hear government reports of devastation for those on the front line and a deeply troubling rising death toll.

In the darkest of times, we look for hopeful symbols of a better future, and the rainbow has been embraced as such by the nation during this crisis. Hand-painted by home-schooled children, over the past few months they have decked windows across the country, the backdrop to daily sanctioned walks or Thursday night applause for the wonderful NHS.

The origins of the rainbow as a hopeful symbol are, of course, biblical. After the deluge, Noah – in his ark full of animals – looked out over the bleak wasteland to a glowing prism in the sky: the promise that life would get better. More recently, it has become the emblem for LGBTQ+ pride. Emblazoned across floats, flags and buildings in cities, the rainbow shines as a hopeful reminder of equality and acceptance.

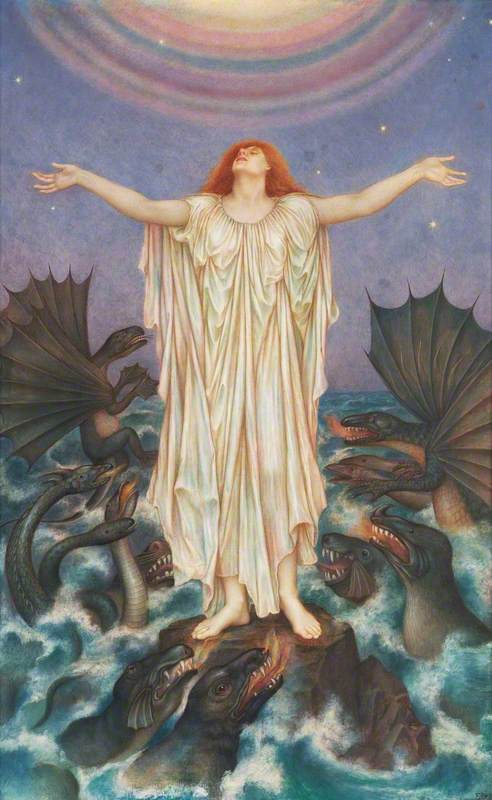

The Light Shineth in Darkness and the Darkness Comprehendeth It Not

1906

Evelyn De Morgan (1855–1919)

Evelyn De Morgan (1855–1919) realised the promising, uplifting potential of rainbows in her artworks as she reconciled her horror at the First World War with her deeply personal paintings.

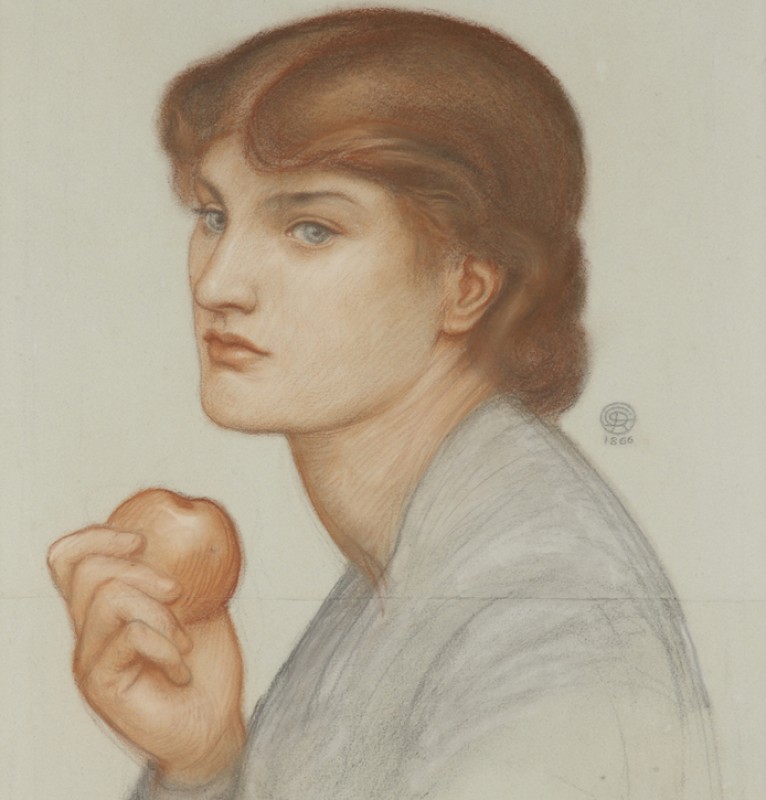

She began her career as a professional artist when she was just 17 years old. She attended the Slade School of Art where she won a full scholarship for her studies. She was able to travel to France and Italy to study the Old Masters, before selling her first painting at the age of 20.

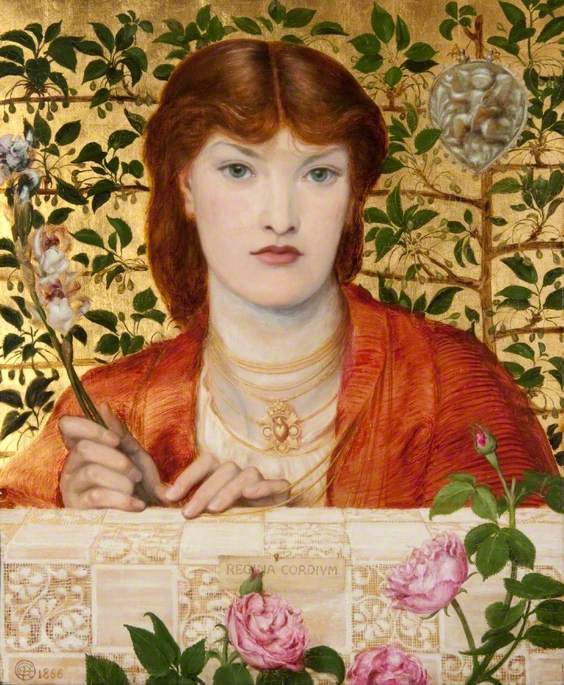

She followed artistic conventions and fashions but employed a rich visual lexicon of colours, motifs and symbols to subvert traditional meaning and present her own political agenda.

Ariadne in Naxos (1877) is one of her earliest paintings in the De Morgan Collection. As the title suggests, the painting is based on the classical story of Ariadne, who assisted Theseus in his defeat of the Minotaur, only to be abandoned by him, then discovered by Bacchus whom she would eventually marry. Typically, renderings of the story focus on her rage or discovery, but De Morgan depicts her as truly abandoned, in a red martyr's robe, removing the blame. Her Ariadne personifies tragic fallen women of the Victorian age, abandoned by their families and society. The beautiful painting is a veil for her feminist agenda.

Death is omnipresent in De Morgan's artwork, unsurprising perhaps considering she was a Spiritualist. Her beliefs were based on Swedenborg's philosophy of the ascension of the immortal soul through human life, to emancipation when the physical body dies. Consequently, her view of death is hopeful and forward-looking, typically personified as an angel of death in her early paintings, such as two eponymously titled works from the 1880s.

The Angel of Death I is in the De Morgan Collection. It is a sensitive and intimate image of the Angel of Death arriving to accompany a woman's soul onward at the end of her physical life – hope is depicted in the fertile landscape and flowers. Death isn't for one to fear, these paintings announce: it is the ascension of the soul to the glorious spirit world of springtime after the winter of death on earth.

War, synonymous with death, was approached by De Morgan in her own uniquely hopeful manner. To justify such a waste of human life, De Morgan attempted to reconcile the horror of war as instrumental to eventual peace. Visually, she realised this ambition by binding together symbols of war and peace in billowing clouds of rainbow mist.

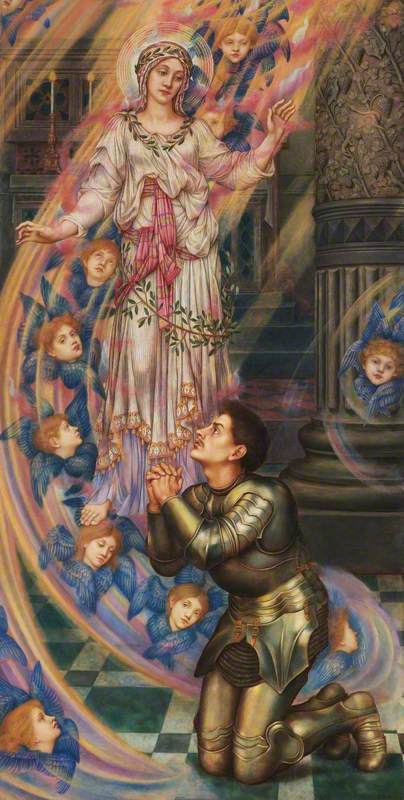

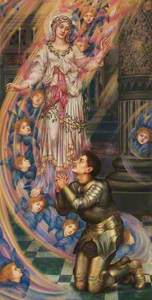

Our Lady of Peace (1907) painted in Italy, echoes a Renaissance altarpiece in its majestic size, tall rectangular form, and dynamic upward composition. A lone soldier, dressed for war in battle armour, has escaped his fate for a moment of calm contemplation in an empty candle-lit church at dusk. As he kneels before the altar – mirroring our own experience of looking up at the painting in the gallery – a vision of the Madonna bursts from the darkness, lighting up the dim interior. She is a tender mother, the promise of watching over the soldier in battle implied by her quiet smile and gesture of peace. A swarm of winged putti hold her afloat in a rainbow spiral, rising around her.

The subject and message are simple: from war comes peace. In contrast, the form and colouring are extraordinary. Thickly applied pink, purple, blue, and yellow paint blazes from the white ground of the canvas, in an upward spiral, colour leading the eye through the composition successfully. To this end, the artist also promotes her belief that the soul is on an upward trajectory through life towards death.

In 1916, the artist held an exhibition in her studio of her war paintings, with the ambition to sell the works to raise funds for the Red Cross. The rainbow glimmered from all of the canvases on display, clearly aligning war with the artist's hope for peace.

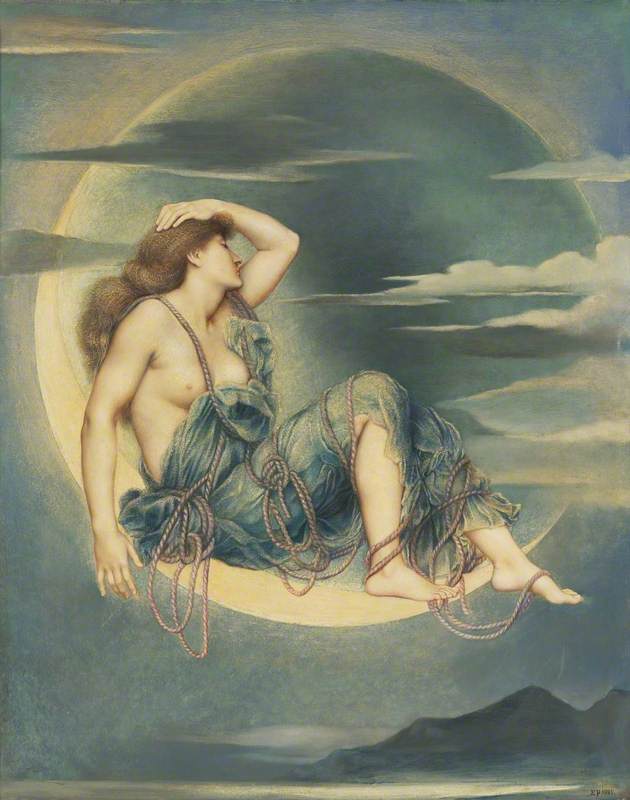

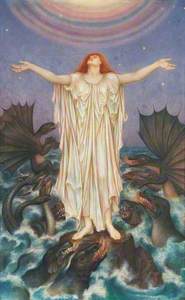

A relatively small painting, SOS (1914) is dominated by a figure in classical white drapery, craning her neck to peer skyward, reaching desperately upwards towards the spectrum which illuminates twilight. Snapping at her feet are demons and sea serpents in choppy, uncertain waters, representing the Great War.

The imagery is so far removed from an accurate portrayal of death on the front line, that it can only be a deeply personal visualisation of the emancipation of the soul. Her literal, spiritual handling of the Morse Code signal for help – SOS – from which the painting takes its title, provides a glimmer of hope in desperate times.

De Morgan's paintings were created over a century ago, in response to an all-consuming world crisis. Unable to paint realistic depictions of the front line, she turned instead to the symbol of the rainbow to present a hopeful message. As we face COVID-19 and its aftermath, De Morgan's paintings – promising eventual peace, and depicting light coming from darkness – might offer some comfort. Just as the First World War passed, we will overcome this crisis.

Sarah Hardy, Curator and Manager, De Morgan Foundation