The central aim of 'Body Vessel Clay: Black Women, Ceramics and Contemporary Art' is to consider the contributions made by Black women to the history of ceramics. It begins with the seminal potter, Ladi Kwali (born c.1925), who worked out of Nigeria in the 1950s until her death in 1984.

But beyond Kwali, the exhibition considers a younger generation of cross-disciplinary artists working with clay, all of whom upend ways of working with the medium both conceptually and traditionally. While some are trained ceramicists, others use the medium in its raw form as a performative tool, making use of clay's tactile, malleable and haptic qualities.

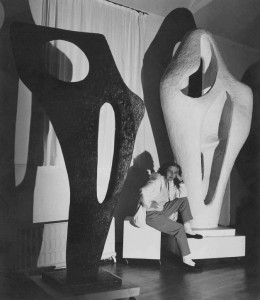

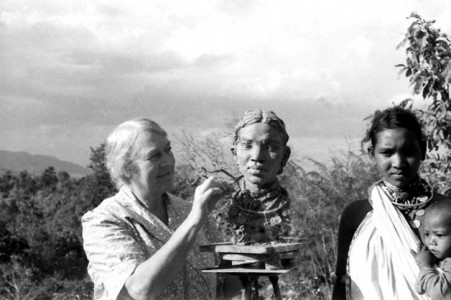

Photograph of Ladi Kwali

This exhibition highlights Gwari traditions and its pottery that informed Kwali's life's work. Importantly it traces the matrilineal passing down of such traditions, women to women, within communities in Nigeria but also across the globe. The exhibition doesn't claim to be a definitive or finite thesis on Ladi Kwali, but through the display of ceramics, objects, archival material, documentary photography, and contemporary works, it looks at 70 years of making by Black women and their relationship to one of the oldest artistic traditions and readily available materials – clay.

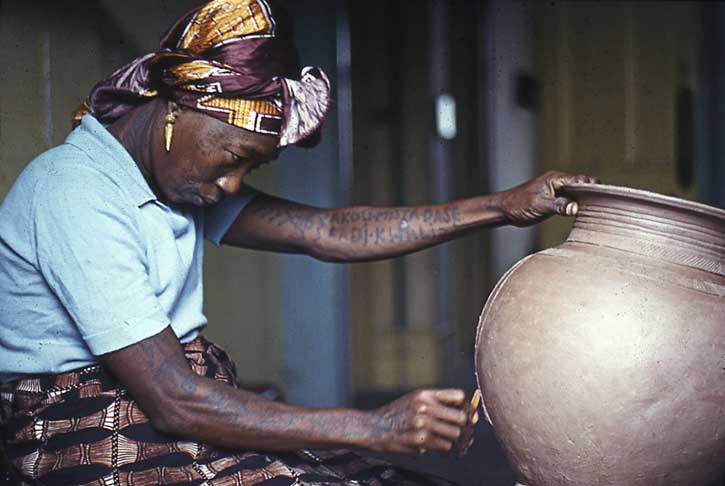

Water Pot

1956–1959, stoneware, chun glaze, slip glaze by Ladi Kwali (c.1925–1984)

As a British-born Nigerian curator, writer and researcher who grew up in both Nigeria and the UK, I have both a personal and professional interest in art histories that speak across both geographies. In conceiving this exhibition, I wanted to unpack how a colonial intervention framed and changed the course of Kwali's indigenous Gwari pottery vernacular, bringing it into dialogue with British Studio Pottery. A hybridity of practice is observed in the resulting ceramic objects (that were once functional) currently on view at Two Temple Place.

In 1950, the late British studio potter, Michael Cardew (1901–1982) arrived in Nigeria, employed as a senior pottery officer by the Nigerian colonial government. He was tasked with setting up small-scale potteries with the initial ambition to set these up across the country. They would serve trainee potters using modern techniques to create fusion ceramicwares (Nigerian and European blended). Intended the local use, the project anticipated the emergence of the middle classes after Nigeria gained independence from colonial rule.

The Pottery Training Centre, Abuja (now Suleja) would be Cardew's sole pottery project during the over 15 years he spent in Nigeria, during which time Ladi Kwali emerged as the centre's star. The exhibition introduces Kwali as a locally celebrated potter from the Kwali village close to an area now known the Federal Capital Territory (FCT), Abuja in northern Nigeria. We know that Kwali was taught pottery by her aunt, continuing the Gwari matrilineal handing down of pottery making from one generation to the next.

Gwari-Nupe pots

1900–1970, stoneware pots by unknown artists

Kwali, like other women from her community, acquired these skills alongside carrying on a range of other domestic duties, such as farming, and looking after the home and children. Kwali was an exception as she was industrious and traded her pots beyond her village, in the city of Minna where, for a time, she had a shop. Her pots often sold out before reaching the market and were collected by Emir Suleiman Barau, the ruler of the Abuja emirate. It was at his palace that Michael Cardew first encountered Kwali's pots which he admired, and with Emir's encouragement, he would invite her to join the centre in 1954.

A history of these key moments is on view in the Lower Gallery individualising Kwali and rooting her work in her hometown as well as attending to Kwali and Cardew's early interactions. The respected design historian Tanya Harrod writes more about this complicated relationship in her book The Last Sane Man: Michael Cardew, Modern Pots, Colonialism, and the Counterculture.

On display are two examples of Gwari-Nupe pots made in the early twentieth century, which reflect what kind of pots Kwali might have made as a young potter, and refer to the pottery traditions predating Cardew's Abuja project. On display are also a number of ceramics created by different generations of makers, from Asibe Ido to Bawa Ushafa, George Sempagala and Halima Audu.

Water jars

by Halima Audu and Ladi Kwali (c.1925–1984)

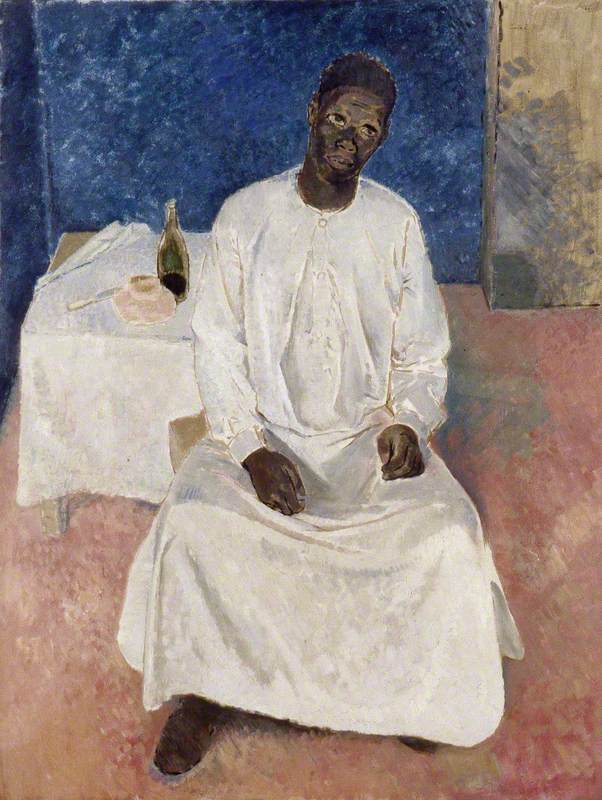

Objects envisioned as ceramics for the self-determined Nigerians after the end of British colonial rule in 1960. The impact of hand-building according to Gwari custom is explored in the early pots of Magdalene Odundo, who developed this style after returning from training with Kwali and others for three months in 1974.

By the staircase of the exhibition, one can view the water jars created by Halima Audu and Ladi Kwali. A talented potter, Audu's career was tragically cut short as she died of yellow fever just two years after arriving at the centre. Each pot often presented its own personality, for example, water jars were often incised with animals and geometric bands that, in my view, mimic body scarification and tattooing practices.

Esinasulo (Water Carrier)

1974–1976, terracotta by Magdalene Odundo (b.1950)

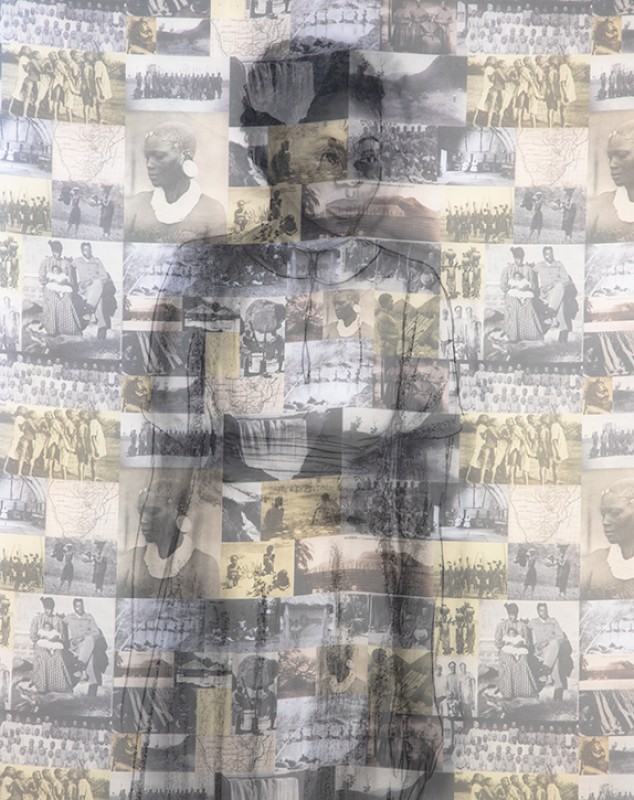

The top floor galleries return to an emphasis on the matrilineal passing down of pottery traditions from Ladi Kwali to Magdalene Odundo, and indirectly to Bisila Noha who explores overlooked African women potters through a contemporary lens.

The contemporary display, A Politics of Clay, is one of potential and possibilities. Clay is inherently political and I wanted to think through how this might be enlivened and conveyed through performance art.

Burdened (film still)

2018, HD video loop, by Julia Phillips

In Julia Phillips' silent black and white film, Burdened (2018) there is so much to unpack in an unidentified torso energetically moving, hips swaying the abruptly cutting to feet pounding onto mounds of clay. A beautiful and poetic burden to have when working with clay is the demand to transform the material by hand (with or without a wheel), before it becomes solid through air drying or firing. Phillips, whose handmade ceramic sculptural objects and tools embody the contradictory nature of many aspects of our contemporary present, evokes a constant negotiation of bodies, boundaries and spaces in flux.

Also featured in the show is Chinasa Vivian Ezugha's Uro, which represents clay symbolically through photographic documentation referencing the original six-hour durational performance commissioned by SPILL Festival of Performance Art in 2018. For Ezugha, clay is a force to be worked with and against in moments of making and unmaking whilst never completely undone.

Still from 'Uro' (a SPILL Commission at SPILL Festival)

2018, film by Vivian Chinasa Ezugha

In the artist's own words:

Uro is about the weight of depression, rebirth and awakening from sleep.

Sitting on the body as a weighty, damp material, it becomes a solid foundation and morphs the body.

Uro, mortar, material, substance, clay. Life, depression, weight, confusion.

Breathe, you are still alive.

Up and down, the chest lifts. Reach for heaven.

Breathe, you are still alive.

– Chinasa Vivian Ezugha, Uro, 2018

The subtle rules the dense (black hole suspension)

2022, stoneware by Phoebe Collings-James (b.1988)

The exhibition begins with the legacy of Ladi Kwali and her unparalleled importance in the history of ceramics in Nigerian and British art. It ends with a younger generation of artists – Jade Montserrat, Phoebe Collings-James and Shawanda Corbett amongst others – who in the footsteps of Kwali, revitalise the medium to tell their stories.

Dr Jareh Das, researcher, writer and independent curator

’Body Vessel Clay: Black Women, Ceramics and Contemporary Art’, is on until 24th April 2022 at Two Temple Place, London. The show will travel to York Art Gallery between 24th June to 18th September 2022