George Frost (1745–1821) stepped out into the cold, sun-drenched air of a late afternoon in early October, ready to shake off his day's work at the office of the Blue Coach in Ipswich by striding towards the Suffolk hills. He would spend the afternoon, as usual, walking and drawing. Numerous and varied in subject, the sketches produced on these expeditions offer us not only a physical footprint of Frost, but an insight into the character of an artist who has, in the shadow of more prominent figures affiliated with the area, evaded public attention.

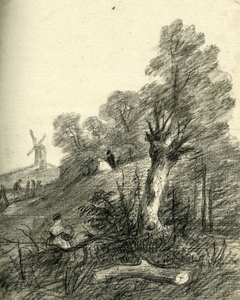

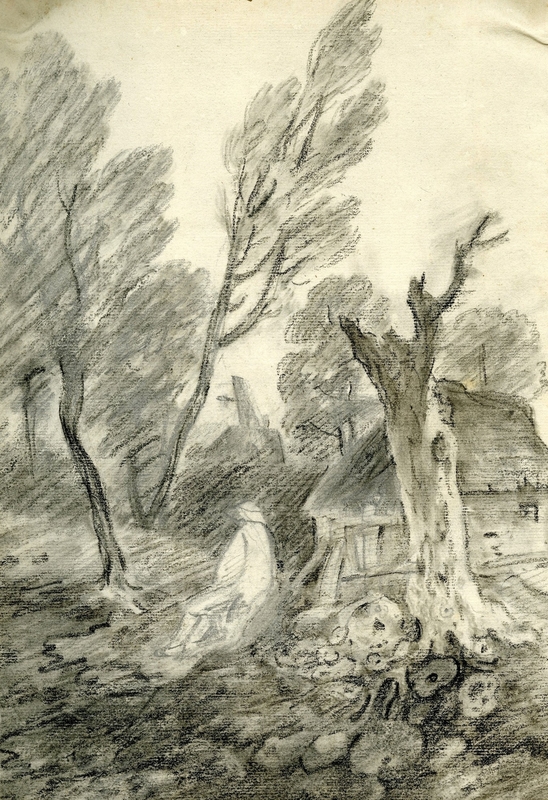

Woodcutter

(included in an album of sketches by G. Frost)

George Frost (1745–1821)

A woodcutter at work, a donkey by a river, cows over fields, a church spied through trees: these sketches tell a story of an insatiable visual appetite. Frost was enchanted by the theatre of the land around him. He always sought to record the scene rather than just the view. Drawing from observation, Frost put himself in the position of a theatregoer. Once one scene has played out, the focus must turn to the next. The window for a faithful rendering of the scene in pencil on paper was therefore tight, and the drawings often present a conflict between a passion for live recording and a commitment to careful observation.

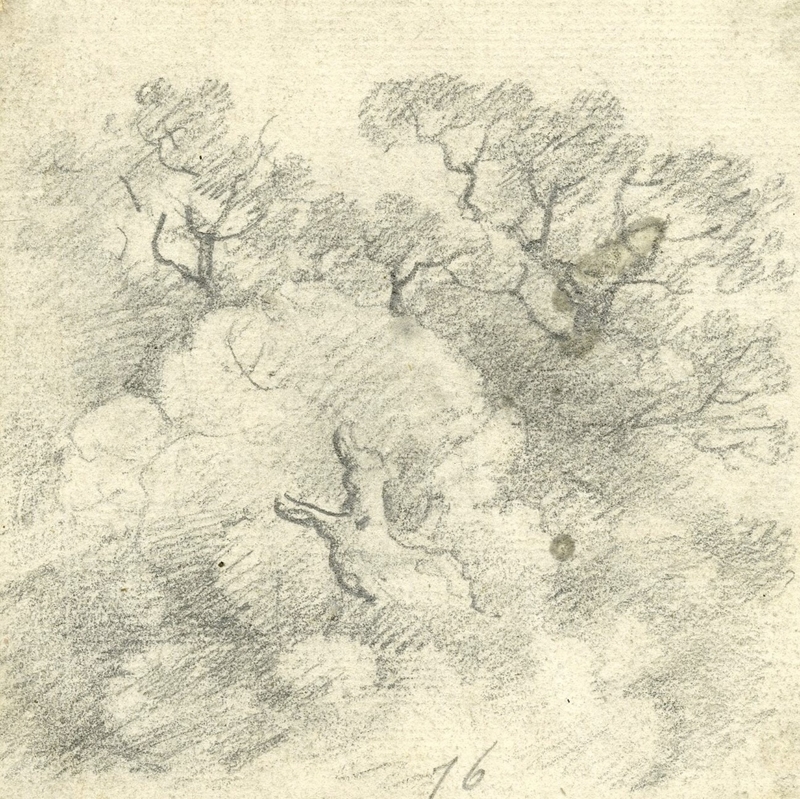

Treetops

(included in an album of sketches once owned by William H. Booth)

George Frost (1745–1821)

Looking up to record a cast of treetops, Frost complicates the border between close study and rapid movement. He takes care to depict the gnarled barks of the trunks, their hollowed areas, the multidirectional branches and the clumps of foliage which, in their arrangements, capture different lights. There is nevertheless a movement in the marks which suggests these treetops are captured on paper with a single glance, the artist eager to move on to the next scene.

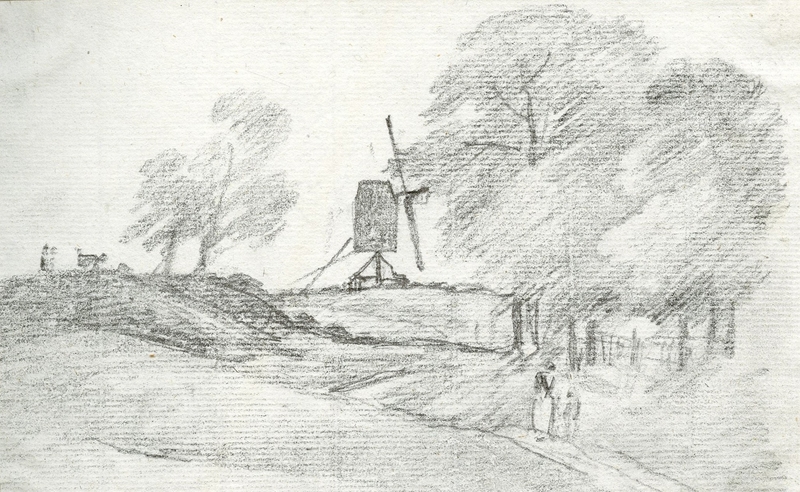

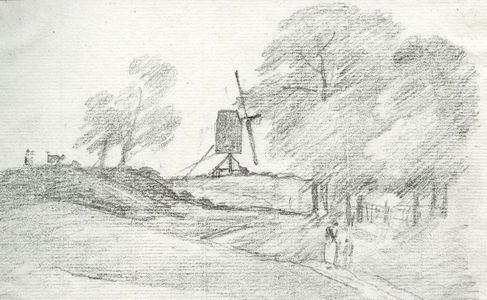

Couple Walking Homewards

(included in an album of sketches by G. Frost)

George Frost (1745–1821)

The country track, presented in a series of half-formed jagged lines, becomes a type of character that runs through Frost's drawings. Incomplete, yet still decipherable and believable as a path for other figures in the drawing, Frost presents completeness as a secondary concern to the pursuit of the present moment and the anticipation of the next.

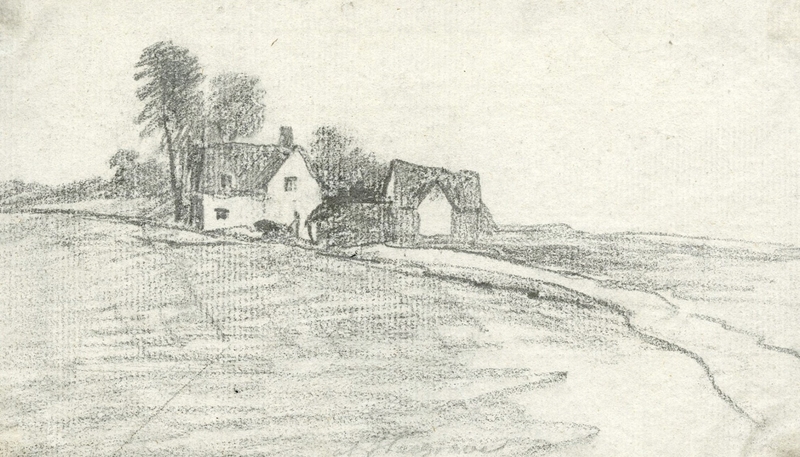

At Hargrave

(Included in an album of sketches by G. Frost)

George Frost (1745–1821)

Despite the connotations of its title, the marks of At Hargrave tell a story of hurried departure. Lines revealing trees, cottages, barns and lanes are laid down in quick singular gestures, before they trail off into the bottom right-hand corner of the page, away from the subjects they depict. As Scene over Meadows highlights, Frost, while searching for detail, is often looking for it beyond his present location. He is always moving, restless, eager to travel beyond the immediate meadow to the figure on the horizon.

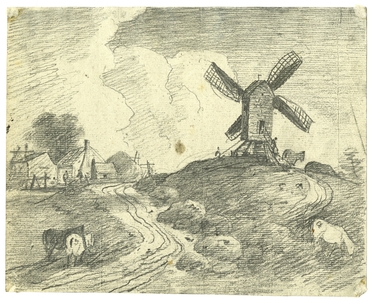

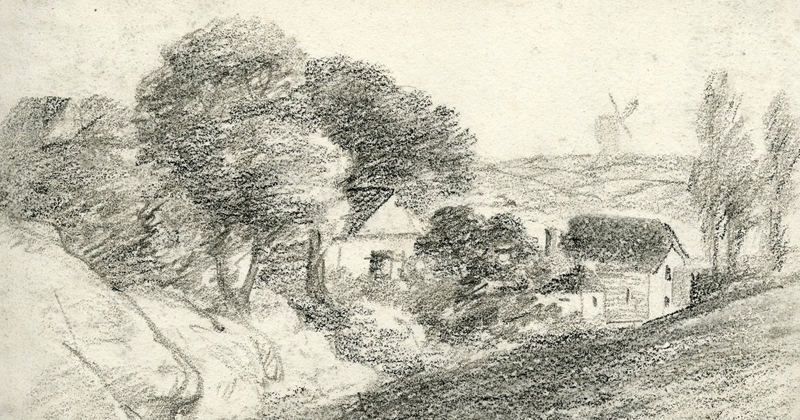

Scene over Meadows

(included in an album of sketches by G. Frost)

George Frost (1745–1821)

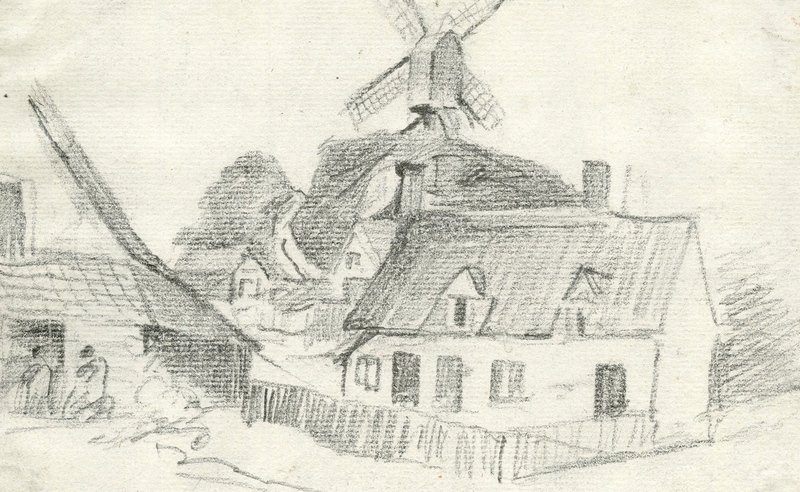

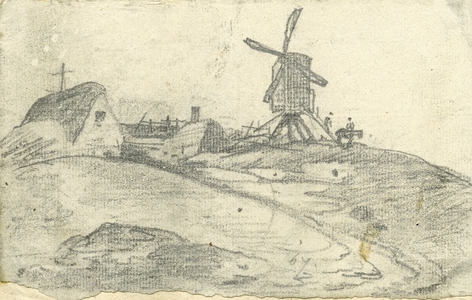

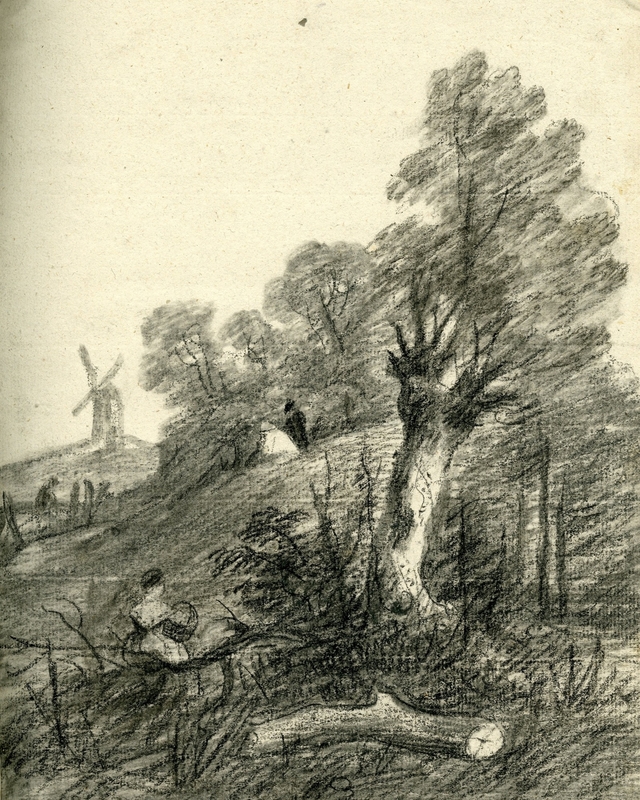

Windmill in Distance

(included in an album of sketches by G. Frost)

George Frost (1745–1821)

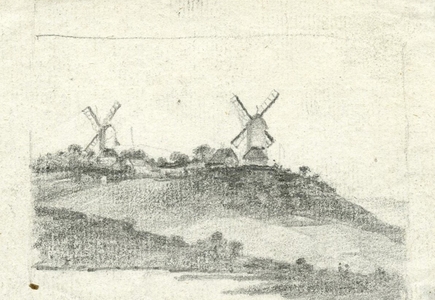

There was, however, one figure whose gravitational pull on Frost exceeded others and revolutionised the artist's way of working. The windmills at Stoke, propelled by the elements into varying states of action, complicated Frost's habit of drawing with a swift glance. They demanded his return, his time and his patience. To truly see and understand these figures, Frost had to slow down and listen to his subject's call for active stillness.

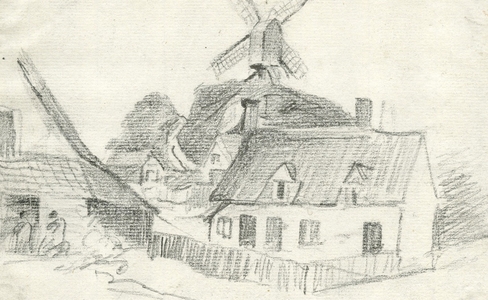

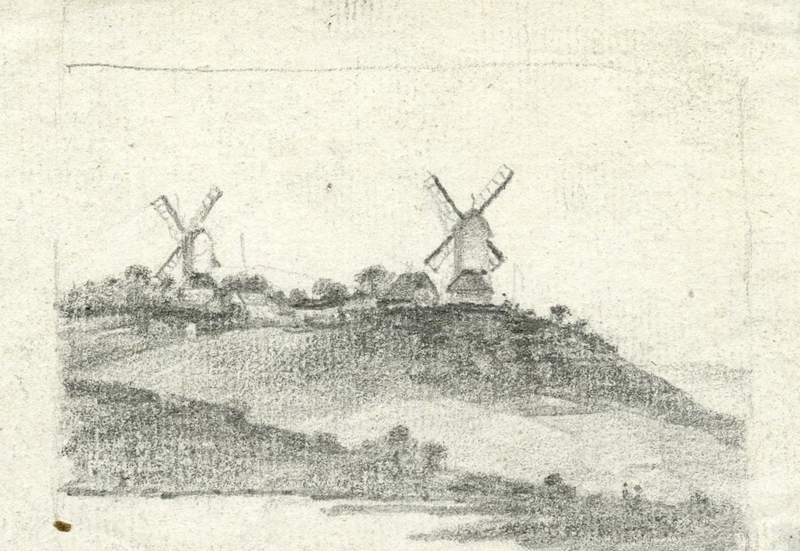

Stoke Hill, Windmills

(included in an album of sketches by G. Frost)

George Frost (1745–1821)

The drawings of the Stoke Mills are striking simply on account of their number. While it is by no means unusual to see more than one of the same type of subject in his albums – cottages, farms, churches and cows abound – Frost reserves the recurrence of the specific, named subject to the 'Stoke Windmills'. This marks a new approach for Frost, of spending time up close with the same subject. He adopts a curiosity with one place, returning to understand it again.

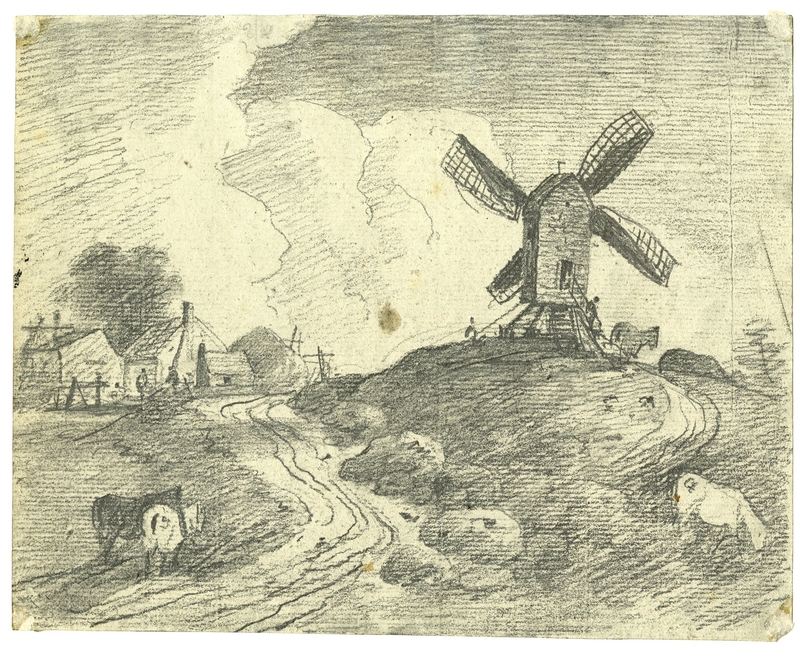

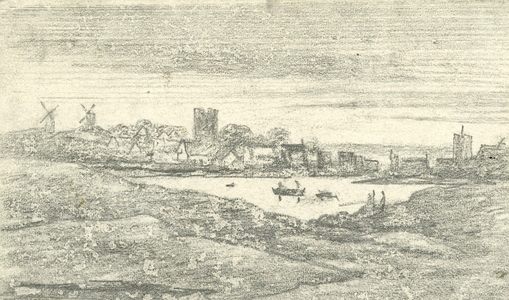

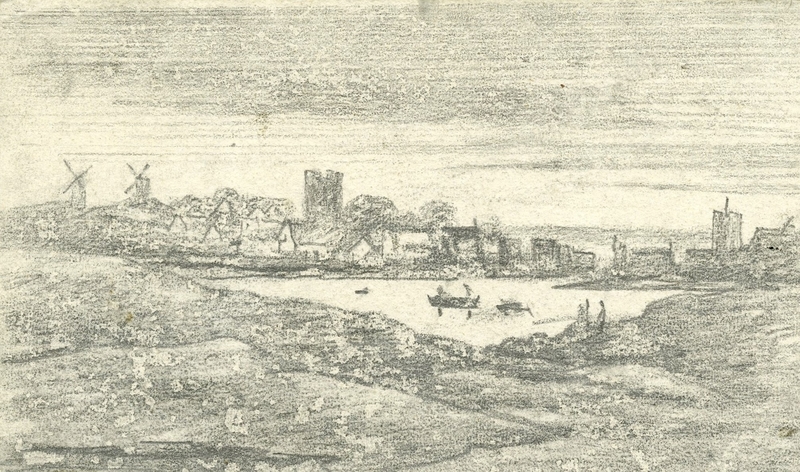

Stoke Windmills and Church

(included in an album of sketches once owned by William H. Booth)

George Frost (1745–1821)

In this drawing Stoke Windmills and Church, Frost demonstrates this new outlook with a way of mark-making predicated on staying rather than leaving. The lines are no longer finding a way to escape the page; they move in, towards the still waters at the heart of the composition.

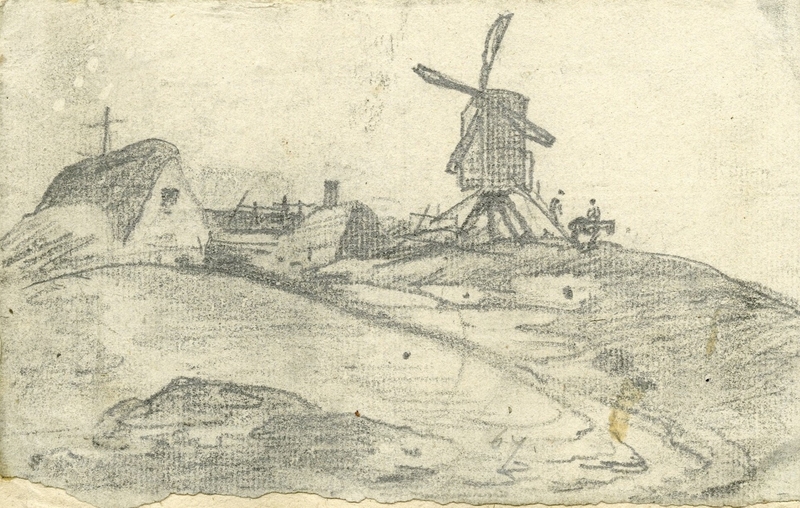

Windmill

(included in an album of sketches once owned by William H. Booth)

George Frost (1745–1821)

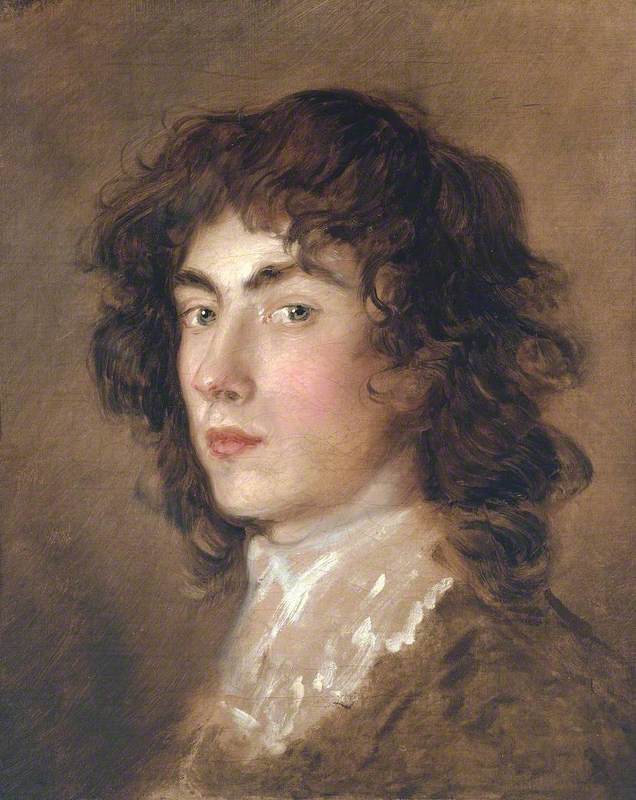

Similarly, in Windmill, there is a consistency of the application that is not present in the study of other subjects. In this drawing, we see Frost beginning to practice the art of bringing human figure and landscape feature together into a whole, carefully constructed mass: a skill Frost learned from an influential figure in his life, Thomas Gainsborough (1727–1788).

Born and raised in Sudbury on the border between Suffolk and Essex, Gainsborough's commitment to capturing rural encounters in Suffolk was an inspiration to Frost, who imitated his idol's work. He even owned one of his paintings, The Mall, which he copied. From Gainsborough, Frost learned how to look harder and how to develop specific drawing techniques.

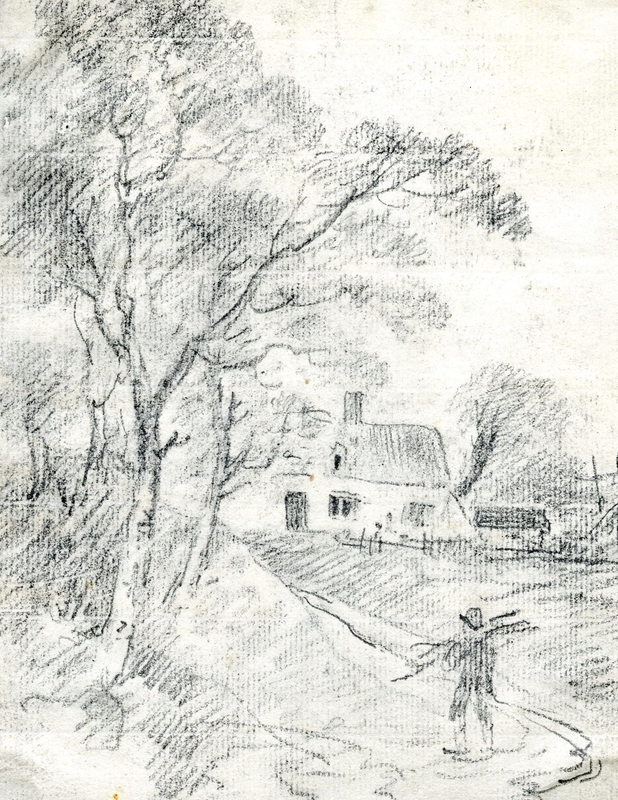

Figure in Landscape

(included in an album of sketches by G. Frost)

George Frost (1745–1821)

Comparing Frost's drawing Figure in Landscape and Gainsborough's Wooded Landscape with Horses, we see the effect Gainsborough had on Frost's work. Frost borrows Gainsborough's use of diagonal shading to harmonise the subjectivities of figure and environment, while reserving the ability to illuminate a particular part of the composition through the use of erased or unmarked space. We can see Frost practising these strategies on the windmills at Stoke, a subject that spurred him to walk further along the jagged, half-formed track of his creative practice.

Figures in Landscape with a Windmill

(included in an album of sketches by G. Frost)

George Frost (1745–1821)

Windmills were a pivotal subject not only for Frost but also artists around him. Stoke Hill proved to be a site of creative circulation, where Gainsborough moved through the work of Frost and into the work of his drawing companion, John Constable (1776–1837). The son of a man who owned mills around nearby Dedham and East Bergholt, Constable was taken by Frost's Gainsborough-like ability to render the structure of the windmill as a figure in communion with other, smaller moments of rural life.

On one of their regular drawing trips to Stoke Hill, Frost and Constable captured different versions of the same scene, involving a figure descending the steps of a windmill, towards a horse and cart on a lane. In their exchange of rural happenings, the two drawings mark the arrival of a shifting dynamic between Constable and Frost that continues to complicate authorial attribution to certain drawings. In a letter written years later, Constable remembered, 'it is a pretty subject […] it is one of the Stoke mills I was at with […] Mr Frost when I did it many years ago.'

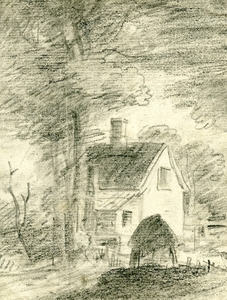

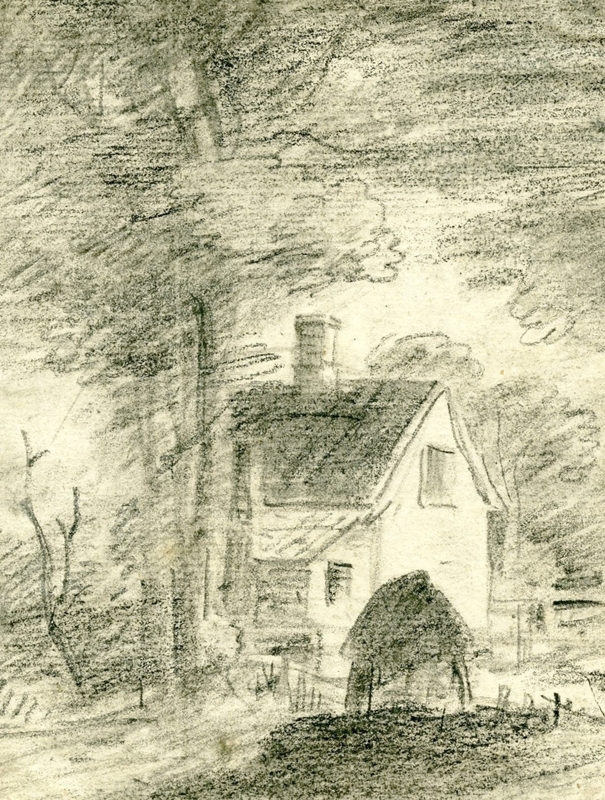

Back of Cottage

(Included in an album of sketches by G. Frost)

George Frost (1745–1821)

A repetition of the collaboration on Stoke Hill, Frost's Back of Cottage and Constable's Water Lane, Stratford St Mary are two drawings of what appears to be the same cottage, using similar strategies albeit from slightly different perspectives. Both drawings adopt the same diagonal shading and shaping of trees typical of Gainsborough's vignettes. In Constable's version, a figure sits in the foreground of the composition, drawing. Whether this is Frost or not, it evidences Constable's desire to watch the work of his contemporaries and stands as a homage to the figure of the drawing companion in art history.

Figures before Cottages

(included in an album of sketches by G. Frost)

George Frost (1745–1821)

An obituary published in the Gentleman's Magazine in 1821 is one of a handful of published pieces on the amateur artist from Suffolk. It underlines Frost's talent at choosing his subjects, but it might be just as true to say that, in some instances, Frost's subjects chose him. 'The subjects which he selected were such as did credit to his taste and judgment; and whatever came from his pencil bore the impress of originality and truth, and evinced, in a bold and masterly manner, the local character and features of the County in which he resided,' the author notes.

Windmill in Landscape

(included in an album of sketches by G. Frost)

George Frost (1745–1821)

The windmill is a figure which has absorbed artists for centuries, sending the practice of drawing sailing through time, passing from one generation to the next. For one amateur artist, it offered a gateway to developing his own practice, and to inspire the work of a friend who would become one of the most renowned artists in history. George Frost, striding towards Stoke Hill in the cold October air, was drawn to practice the poetics of his subject: be still, and be moved.

Edward Richards, writer

This content was funded by the Bridget Riley Art Foundation

Further reading

R. B. Beckett, ed., John Constable's Correspondence, Suffolk Records Society, 1962–1978

Ian Fleming-Williams, Constable and his Drawings, Philip Wilson Publishers Ltd, 1990

Ian Fleming-Williams and Leslie Parris, The Discovery of Constable, Hamilton, 1984