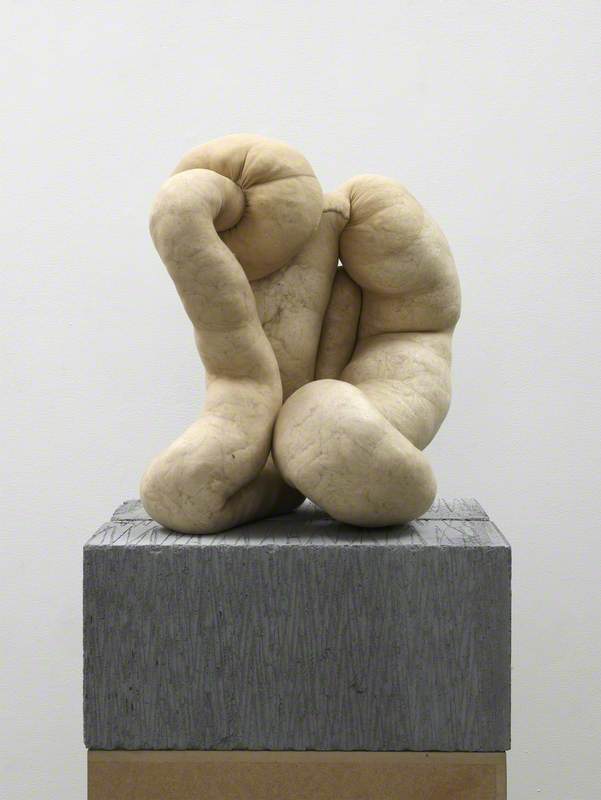

Working in the stonemason's yard at Studio Carlo Nicoli in Carrara, Italy, leading Irish artist Dorothy Cross came across a small block of marble known as Damascus Rose.

© the artist. Image credit: Frith Street Gallery, London

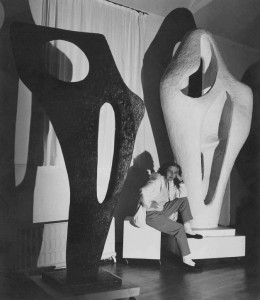

'Red Erratic' at Studio Carlo Nicoli, Carrara, Italy

Damascus Rose sculpture by Dorothy Cross (b.1956)

Inspired by its meat-like, veinous appearance, as well as how the marble's name conjured the current upheaval in Syria, Cross carved a number of new works – currently on show at Frith Street Gallery, London until 14th April – that evoke ideas of war, ruin and migration. These large concerns play out in small sculptural interventions that are indicative of Cross' idiosyncratic practice.

Image credit: Frith Street Gallery, London

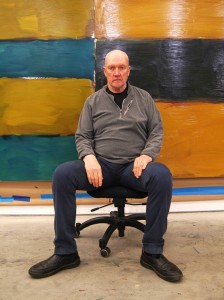

Installation view of 'Dorothy Cross: Damascus Rose' at Frith Street Gallery, London

Red Baby (2021) is a sculpture made from Damascus Rose and carved in the shape of a pillow, an ear protruding from its centre. Cut off from the rest of the body, the ear appears fragile, a modern fossil. Elsewhere, in Red Erratic (2021), disembodied feet scramble across a large slab of fleshy marble in a poignant comment on displacement.

© the artist. Image credit: Frith Street Gallery, London

Red Baby

2021, Damascus Rose sculpture by Dorothy Cross (b.1956)

Cross' oeuvre is in fact filled with unmoored body parts and hybrid forms: the largest bronze crab in Family (2005) has a penis grotesquely bulging out of its shell, while her bronze sculptures of slender foxgloves (2007–2021) include casts of fingertips.

© the artist. Image credit: Frith Street Gallery, London

Family

2005, cast bronze sculpture by Dorothy Cross (b.1956)

It's not the first time Cross has worked with marble – see her monumental Bed from 2017 – yet this particular material is misleading given the often fragile, ephemeral nature of her work. Encompassing sculpture, photography, video and performance, Cross sets up strange encounters between disparate objects and treats a variety of materials – from marble and bronze to family heirlooms and whale bones – with equal admiration. As the strange bodily mutations in her work suggest, she is interested in the divide between animal and human, frequently focusing on organic matter and natural forms.

Born in Cork in 1956, Cross was a champion swimmer before attending the Crawford Municipal School of Art and later moving to England to study jewellery and 3D design at Leicester Polytechnic from 1974–1977. Following an MFA in printmaking at the San Francisco Art Institute in California, she returned to Ireland in 1983. Her home in Connemara, on Ireland's rugged west coast, is an apt setting for an artist so preoccupied with nature, ecology and the sea.

Early works, made while she was living in the US, saw Cross confront Irish society and identity, deconstructing ideas around Mother Ireland (in particular her MFA show 'Matriarchal' in 1982). Back in Ireland, Cross took aim at the Catholic Church against the backdrop of the anti-abortion referendum in 1983, producing phallic wooden contraptions in a challenge to patriarchal structures.

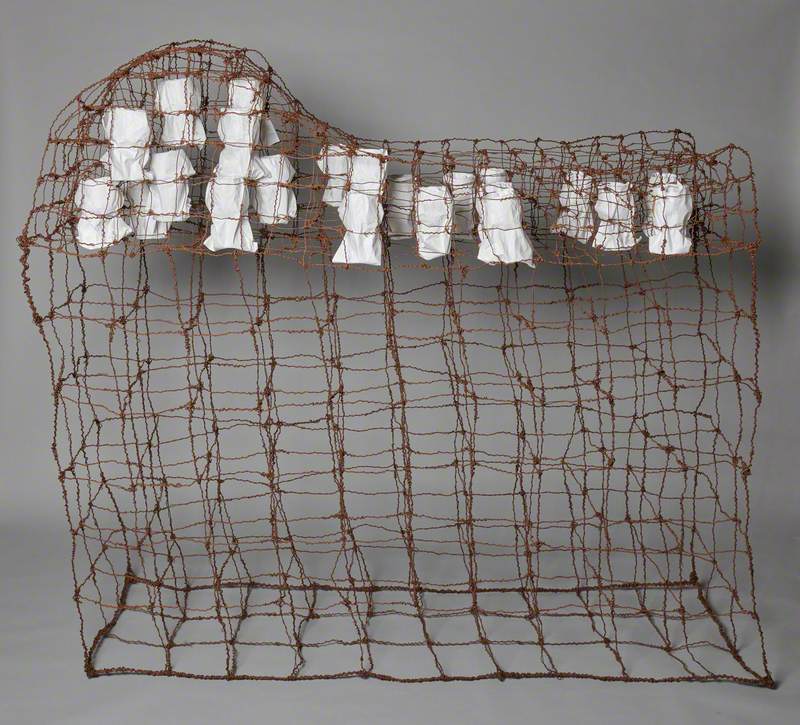

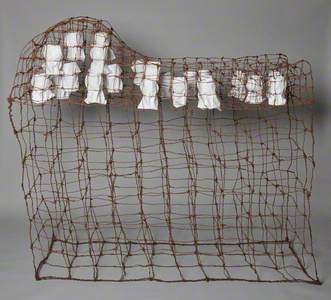

Cross' first major solo exhibition, entitled 'Ebb' and staged at the Douglas Hyde Gallery, Dublin, in 1988, explored ideas around sexuality and gender stereotypes. Later works such as Passion Bed (1991), a large wire structure in which delicate glasses etched with the image of a shark are suspended, reveal her broader probing of gender, desire and repression.

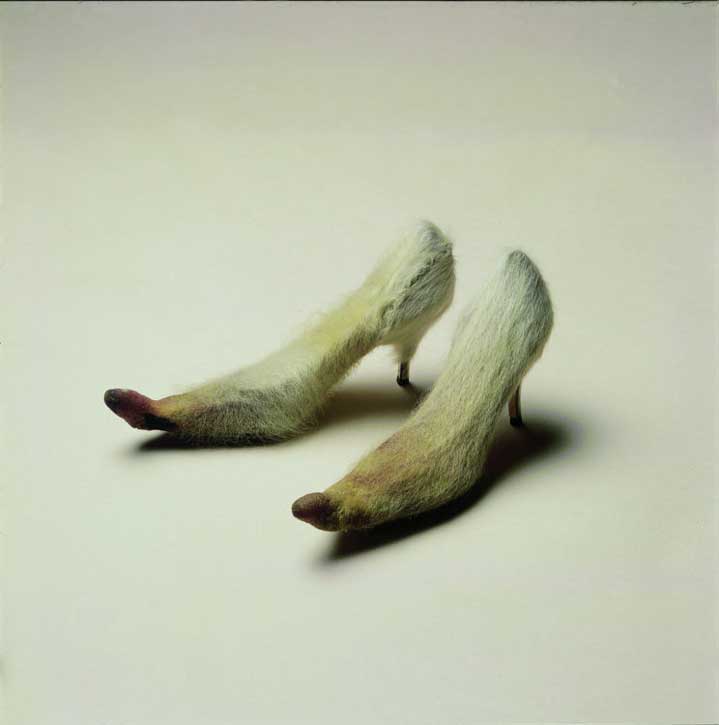

Cross came to prominence in the 1990s for a series of works using the skins and udders of real cows, which she often combined with everyday objects to uncanny effect. In Dish Covers (1993), cow udders hang below silver-plated dish covers, while Stiletto (1994) depicts cow teats attached to the tip of fur-covered high heels.

© the artist. Image credit: Kerlin Gallery

Stilettos

1994, shoes, cowhide & cows teats by Dorothy Cross (b.1956)

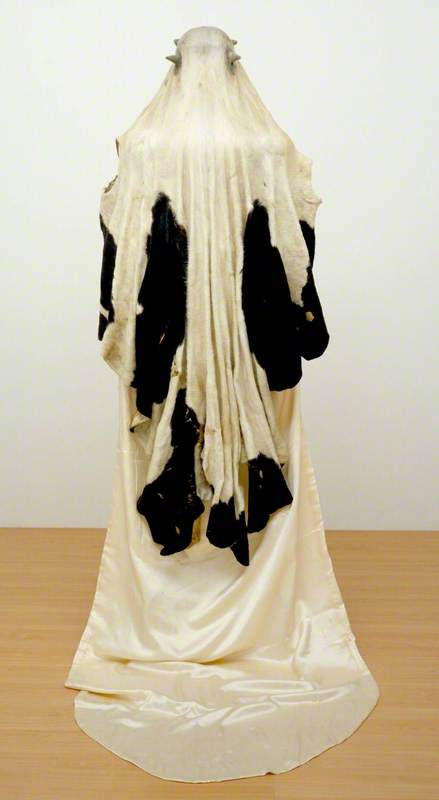

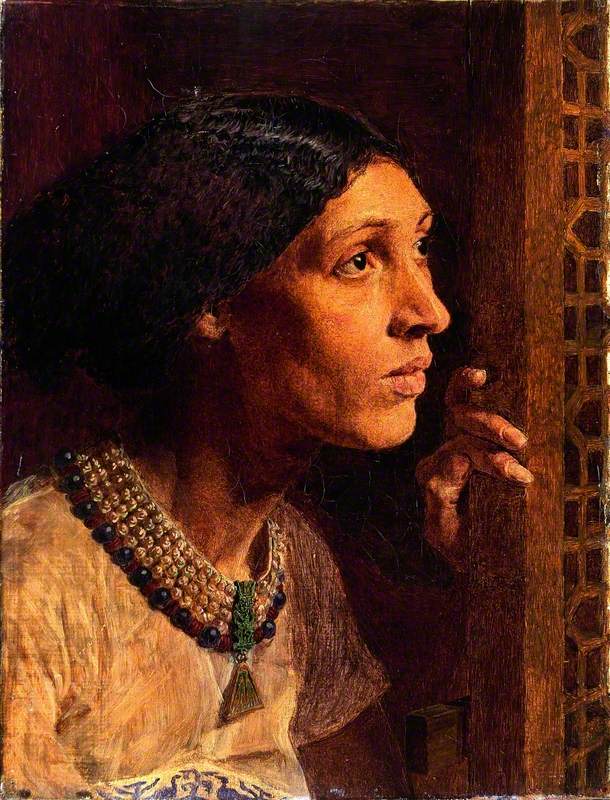

Virgin Shroud, first shown as part of Ireland's exhibition at Venice in 1993, features a statue covered in cowhide and draped with the satin train of a wedding dress gifted to the artist by her grandmother.

Clearly indebted to the surrealist works of Méret Oppenheim, Virgin Shroud, in its conjuring of the Virgin Mary, is a deliberate rebuke to religious statuary and femininity, while also making a link between mammals, milk and mothering. It suggests the symbiotic relationship between animal and human.

In Crossing, a new book examining Cross' unique career, critic Declan Long writes: 'For more than four decades, her evolving, formally open-ended body of work has involved insistent openness to biologically diverse bodies.' In the 2002 film Jellyfish Lake, Cross floats naked amongst millions of Golden Jellyfish in a marine lake in Palau, Micronesia in a literal collision with a non-human species.

© the artist. Image credit: Frith Street Gallery, London

Medusae

2003, film still by Dorothy Cross (b.1956)

For Medusae (2003), a collaboration with her zoologist brother Tom, Cross combined research into the Irish naturalist Maude Delap, who bred jellyfish on Valentia Island, County Kerry, with real-life observation of a deadly species of jellyfish called Chironex fleckeri, also known as the Australian box jelly.

© the artist. Image credit: Frith Street Gallery, London

Installation view of 'Medusae'

2003, film installation by Dorothy Cross (b.1956)

Alongside jellyfish, the shark is a recurring theme throughout her work. Since Shark Lady in a Ball Dress (1988), more recent pieces such as Everest Shark (2014), in which the dorsal fin is replaced by a model of the titular mountain, and Shark Eye (2015), which she embedded in the gallery wall, have explored this out-of-sight fish as a source of fear and misunderstanding.

© the artist. Image credit: Frith Street Gallery, London

Everest Shark

2013, bronze by Dorothy Cross (b.1956)

© the artist. Image credit: Frith Street Gallery, London

Basking Shark

2013, basking shark skin & wooden currach frame by Dorothy Cross (b.1956)

In Basking Shark Currach (2013), the remains of which Cross found washed up on shore, the shark's skin is overlaid onto a traditional Irish boat in a bridge between one world and another.

Since the beginning of her career, Cross has been sensitive to location. In 1999, she presented the pivotal public project Ghostship, in which she painted a disused lightship with phosphorescent paint and moored it in Dun Laoghaire harbour where it shone at night for several weeks. A homage to the lightships that once lined the Irish coast so as to alert to passing dangers, Ghostship cut a spectral figure in its fleeting memorialisation of these once familiar sights.

© the copyright holder. Image credit: the photographer (source: a-n The Artists Information Company)

Dorothy Cross with a model of 'Ghostship'

1998, photograph by unknown artist

© the artist. Image credit: Frith Street Gallery, London

Ghostship

1999, film still by Dorothy Cross (b.1956)

A companion piece to this earlier work, Heartship from 2019 saw Cross make use of an Irish naval ship in Cork harbour in tribute to the Irish Naval Service vessels that had been active in helping save the lives of migrants in the Mediterranean. Onboard the ship was a real human heart encased in metal, borrowed from the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford; its inclusion within this work marked something of a homecoming, given that it had first been found in Cork in the mid-1800s.

© the artist. Image credit: Frith Street Gallery, London

Heartship

2019, performance featuring the singer Lisa Hannigan by Dorothy Cross (b.1956). Commissioned for Sounds from a Safe Harbour, Cork

Various other unexpected or charged sites include an underground toilet in London (Attendant, 1992), a Byzantine temple in Turkey (Snake, 1997), a shell grotto in Margate (Shell Grotto, 2013; part of Cross' first public exhibition in the UK at Turner Contemporary) and a slate quarry on Valentia Island.

© the artist. Image credit: the photographer (source: a-n The Artists Information Company)

'Attendant' installed in underground toilet, Spitalfields, London

1992, cast bronze by Dorothy Cross (b.1956)

Just as the opera Stabat Mater (2004) responded to the quarry's history as a mine and a place of worship, Stalactite from 2011 – an opera first staged in a former brewery in Cork – features a video-projection of a naturally occurring ancient stalactite in Doolin, County Clare, below which a young boy sings, to make a poignant point about human and geological time.

© the artist. Image credit: Frith Street Gallery, London

Stalactite

2010, film still by Dorothy Cross (b.1956)

These site-specific projects, and their associated ephemerality, speak to the senses of loss and disappearance that are, as art historian Robin Lydenberg has argued, at the core of Cross' work. And yet, in her use of found objects and her attentiveness to the natural world, Cross makes permanent or visible that which might often be overlooked.

Imelda Barnard, freelance writer and editor

'Dorothy Cross: Damascus Rose' is at Frith St Gallery, London until 14th April 2022