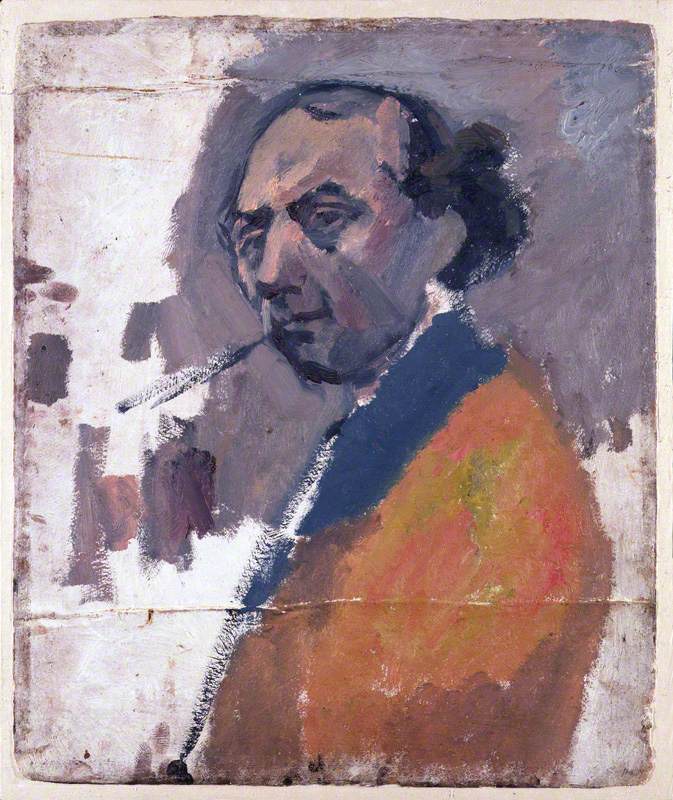

Until quite recently, Ithell Colquhoun (1906–1988) has been an obscure figure within British Surrealism, frequently outshined in reputation by contemporaries Leonora Carrington, Eileen Agar and Leonor Fini. Little was known about her except that she was an occultist and that her brief, shining encounter with the British Surrealists ended up with her walking away from the group in 1940.

With the 2019 acquisition by the Tate of Colquhoun's tremendous 5,000-piece archive, previously held by the National Trust, Colquhoun is about to emerge from the shadows. Although it is tempting to think of this increasing visibility as the process of discovering a 'lost' woman Surrealist, it might be more accurate to consider that cultural forces are converging in a way to allow Ithell Colquhoun's unique artistic vision to shine through like at no time in recent history.

Despite her languishing on the margins of art history, for several decades Colquhoun has had a reputation in the occult world for her 1975 history of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, The Sword of Wisdom, and her delightfully idiosyncratic 1950s rural psychogeographies of Ireland and Cornwall, Crying of the Wind: Ireland (1955) and The Living Stones: Cornwall (1957). In the last decade, a fresh reconsideration of esotericism in art has created the conditions where we can more fully appreciate Colquhoun's sustained occult practice and esoteric worldview as the most profound driving force behind her art and writing.

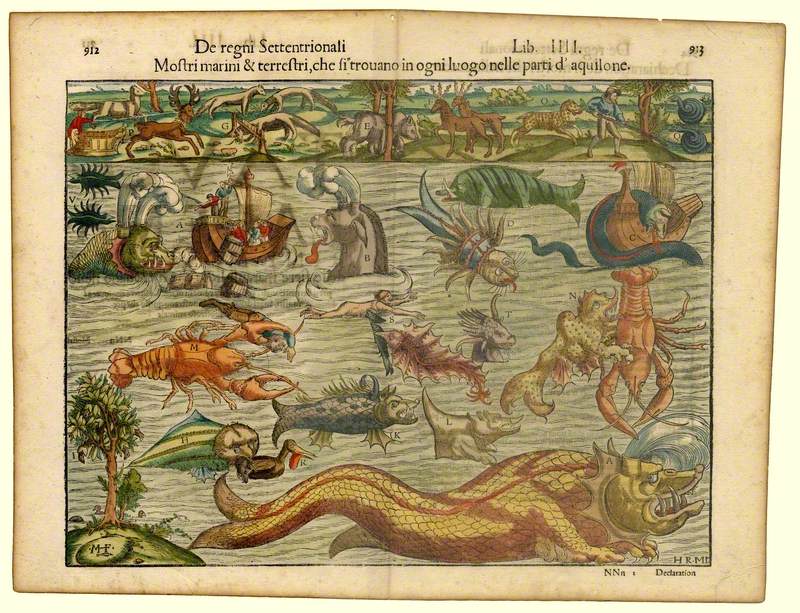

Colquhoun was comfortable walking between worlds. Born in 1906 in India to a family of civil servants who had served in India for generations, she existed in a liminal space with respect to her own cultural identity. Not at all Indian, not comfortably English and deeply inspired by W. B. Yeats, Colquhoun forged a Celtic identity for herself which to her mind supported her dreamy, artistic, and mystic propensities, and which ultimately led her to Cornwall in the 1940s. Colquhoun's interest in both the occult and the visual arts were evident at a young age. Early school notebooks contained scribblings on the zodiac, the magical properties of perfumes, and symbols related to plants, birds and planets. In 1926, as a student at Cheltenham Art School, she wrote a short yet complex play, The Bird of Hermes, based on alchemical manuscripts, demonstrating her command of difficult esoteric themes.

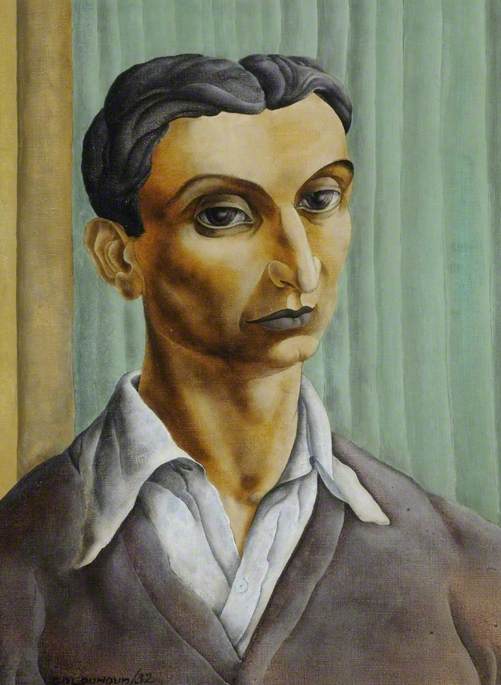

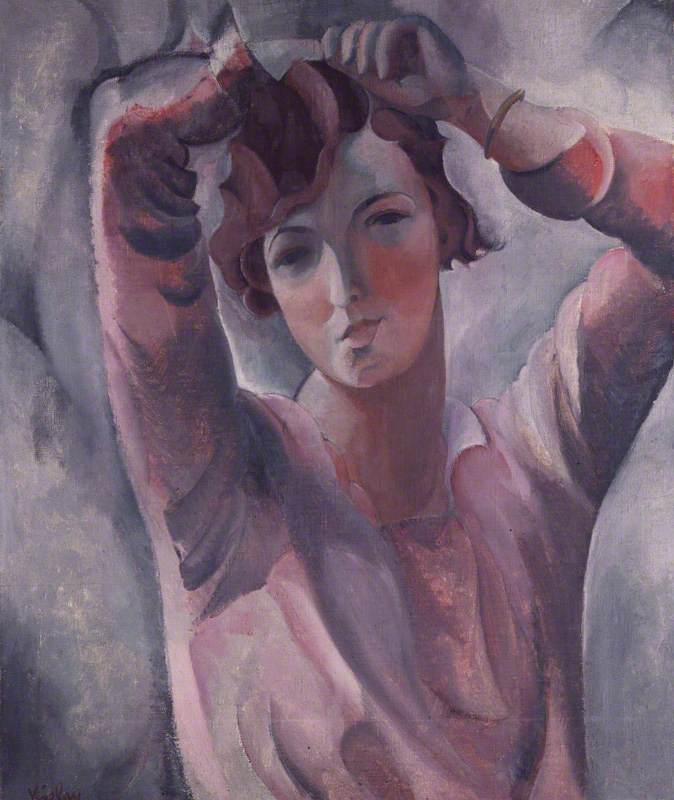

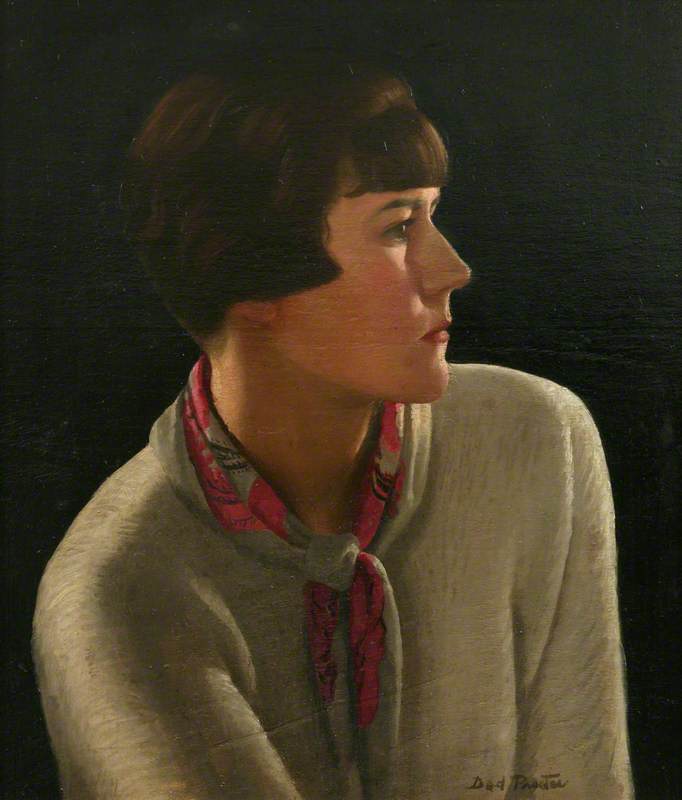

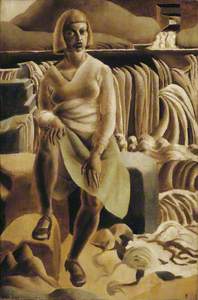

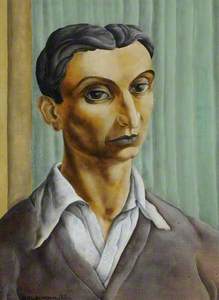

In 1927 Colquhoun enrolled in the Slade, where she balanced her classical arts training with her own growing interest in occultism, embracing London's occult scene. While at school she tackled large canvases dealing with classical and biblical themes, such as her award-winning Judith with the Head of Holofernes (1929), and outside of class, she learned about the Kabbalah and alchemy under the tutelage of her cousin, Edward Garstin, who was a member of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. Although she was initially refused admission to the Golden Dawn in the 1930s, this encounter began her lifelong love affair with the principles of the Golden Dawn, infusing her art with elements of occult colour theory and sacred geometry that she embraced through the last decade of her life.

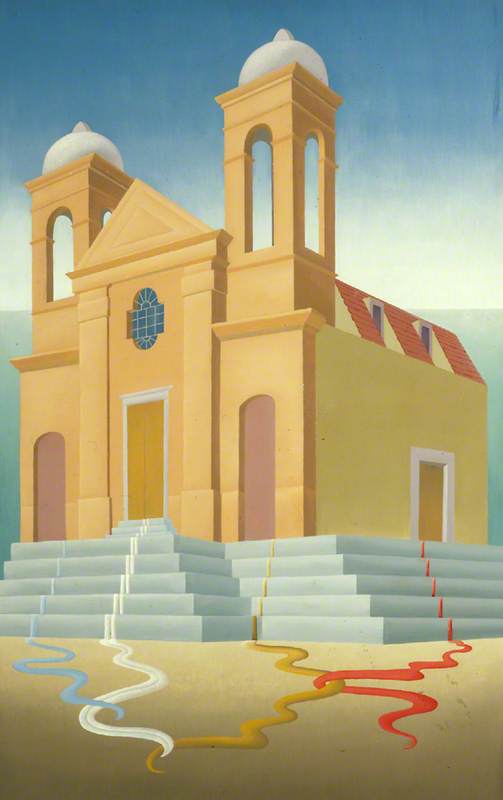

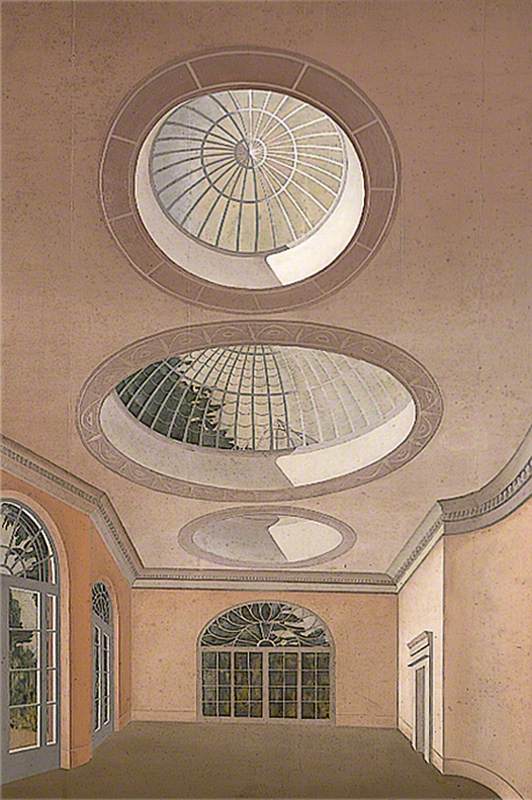

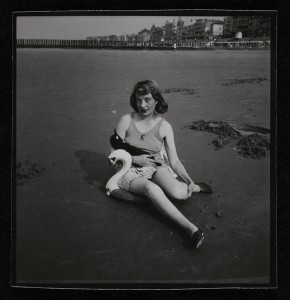

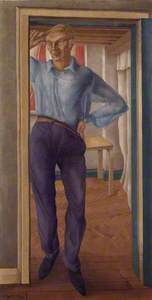

After earning her diploma from the Slade, she spent the early 1930s defying any societal expectations for a young woman of that era, sketching and painting in Paris and Greece, having a liaison with a married man and falling in love with a woman. Her work from this time reflected the architecture of her travels and her interests in the natural world, and it is through her detailed botanical studies that we can trace her stylistic slide into Surrealism.

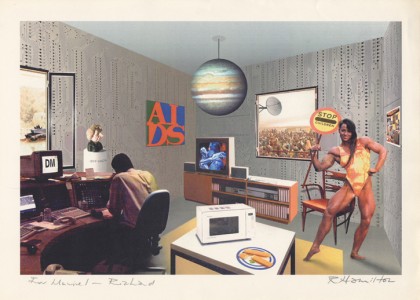

In 1936 Colquhoun's life was changed by the spectacular 'London International Surrealist Exhibition' where she encountered the magnetic antics of Salvador Dalí. By 1939 she was at the centre of British Surrealism, contributing to a joint show with Ronald Penrose at the Mayor Gallery and writing pieces for The London Bulletin, the showcase publication for Surrealist and avant-garde art and writing in Britain.

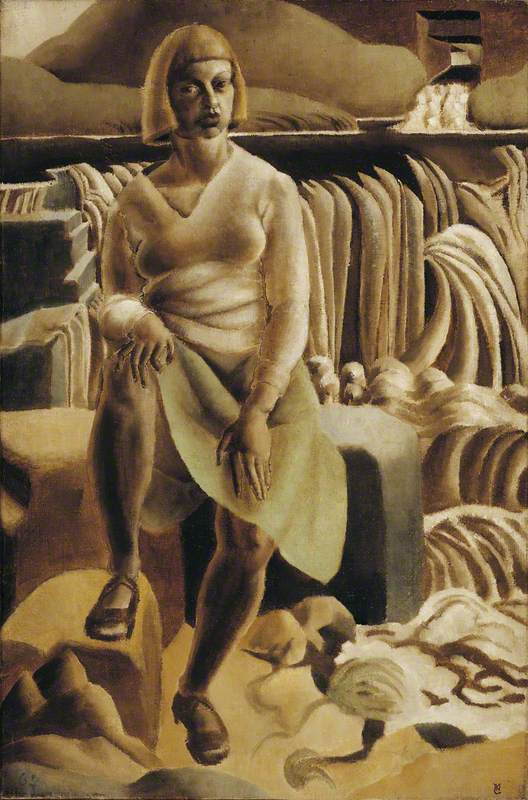

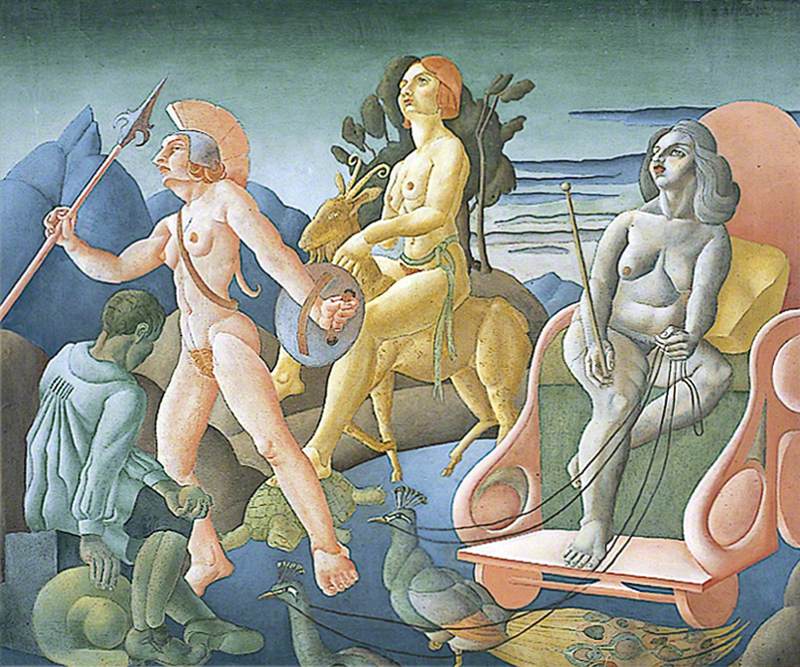

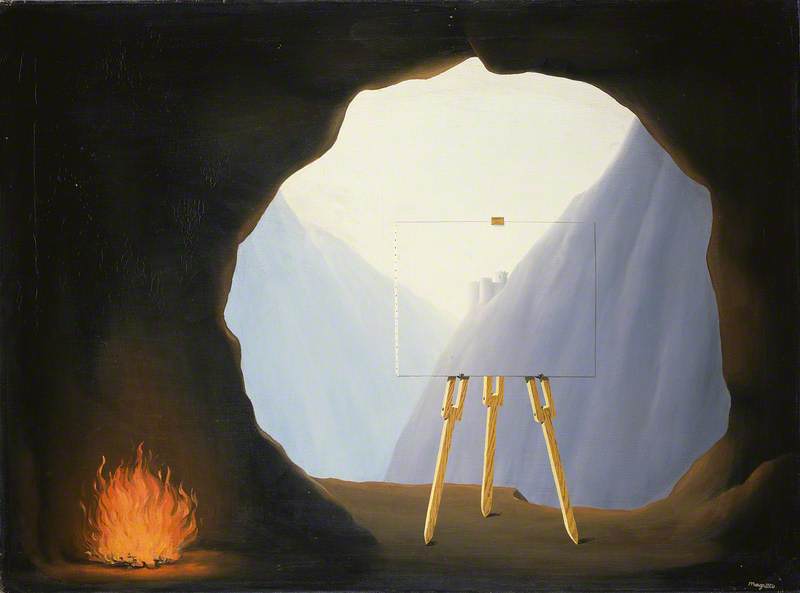

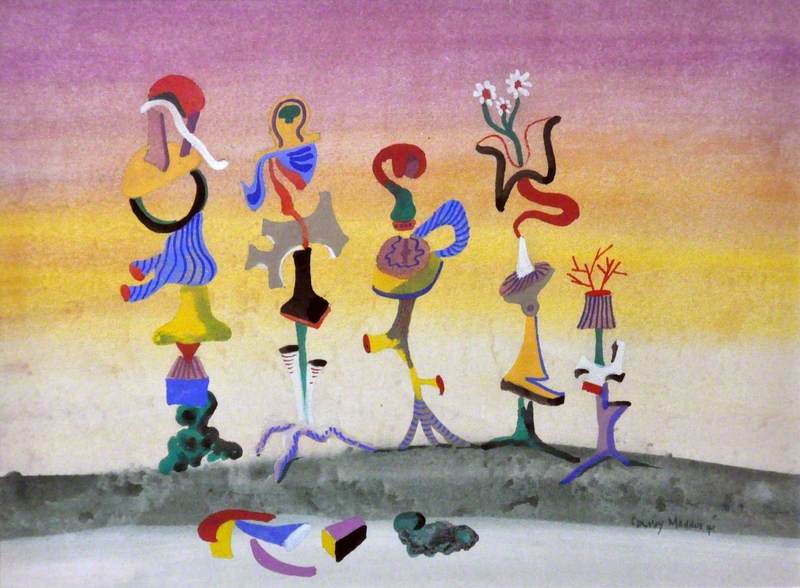

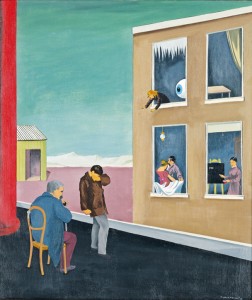

Colquhoun's early Surrealism shows the visual influence of Dalí and Magritte, while she continues to use natural forms to tell stories of sex, death and decay in the shadow of the Second World War. Her work at this stage is filled with metaphor that was propelled by her own professed animism.

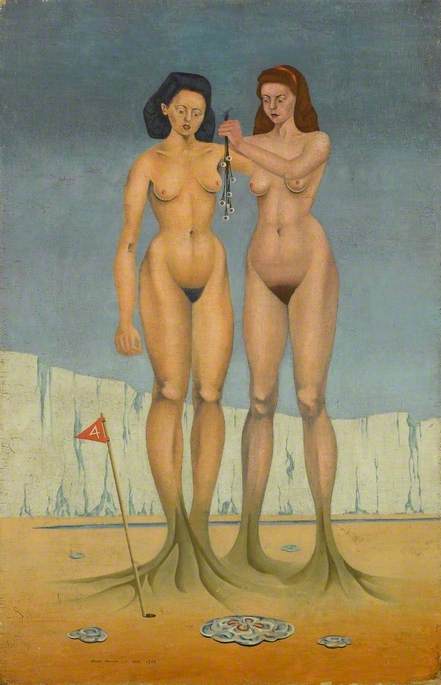

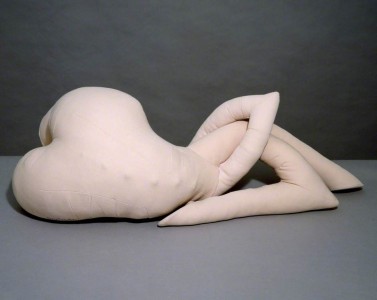

Several pieces reflect her mythic exploration of castration and impotence, recalling the Fisher King, the ruler whose lands are suffering from the sovereign's loss of vitality. Gouffres amers (1939) explicitly shows the male body in a state of decay, being reclaimed by nature. Conversely, images suggesting female bodies are lush and inviting, as we see in the more playful Scylla (1938).

The ultimate trajectory of Colquhoun's Surrealism was perhaps most influenced by her time at the Surrealist gathering organised by Roberto Matta and Gordon Onslow Ford in Chemilieu in western France in the summer of 1939. There she met with like minds who had been influenced by the writings of esotericist P. D. Ouspensky, exploring theories of extra dimensions, and the occult role of the artist as magician. Very likely these encounters inspired Colquhoun's own later oracular approach to automatism, the Surrealist techniques designed to help bypass the artist's conscious mind to penetrate the symbols of the collective unconscious.

Although it is commonly thought that Colquhoun left or was expelled by the British Surrealists because of her occult interests, a more nuanced explanation was that Colquhoun was fiercely independent and refused to be constrained by Edouard Mesens' rather autocratic attempts to curtail any further disintegration of a British Surrealism that was already on the rocks by 1940. She wished to be free to write for whom she wanted, join any group she wished, and did not want to be forced to support political movements that she felt were incompatible with a creative life.

Yet it is true that Colquhoun's occultism was centrally important to her, and from 1939 to around 1942, parallel to her relationship with the British Surrealists, her private magical experiments show an explosion of her own occult thinking, especially related to the energies of the body and the magnetic currents of the land. She painted a series of explicit, alchemically inspired, erotic prints detailing her theories of the creation of the Divine Androgyne through sexual union.

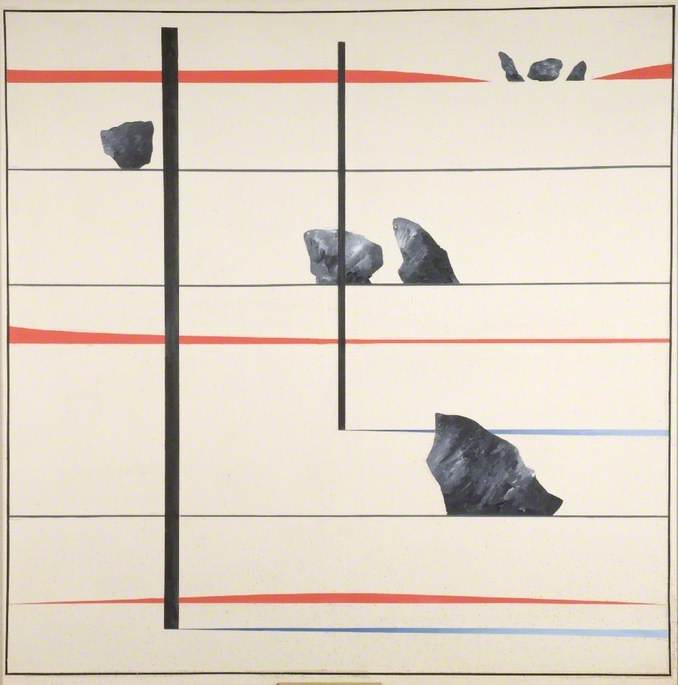

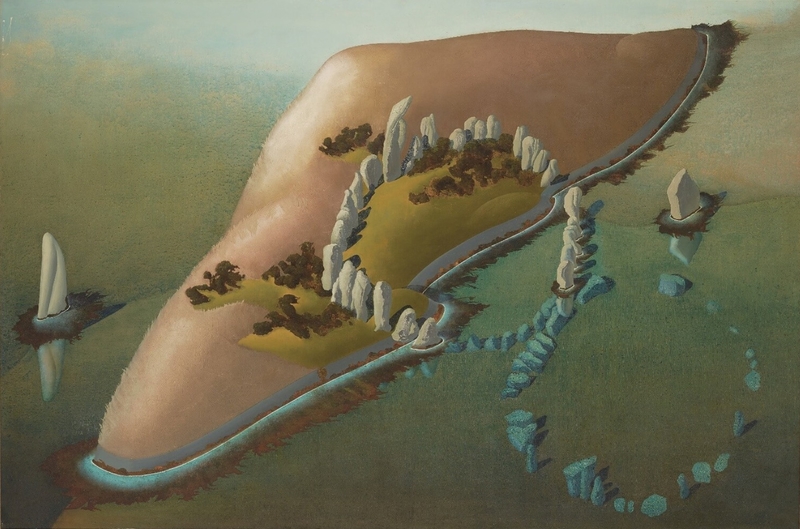

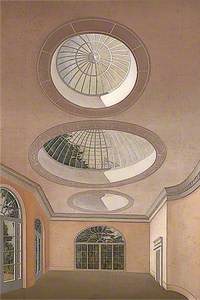

She painted representations of humans and landscapes in fourth-dimensional spaces, detailing points where energy flows can be exchanged between people and stones. There are sketches of sacred landscapes as portals to other realms. Likely many of these experiments were never meant to be displayed, but during this time Colquhoun was developing her complex world view, where, as artist and seer, she would cultivate the ability to access other realms and dimensions through colour and form. In these experiments, Colquhoun also affirms the importance of the Divine Feminine to any sort of spiritual attainment, a constant theme in all of her art and writing.

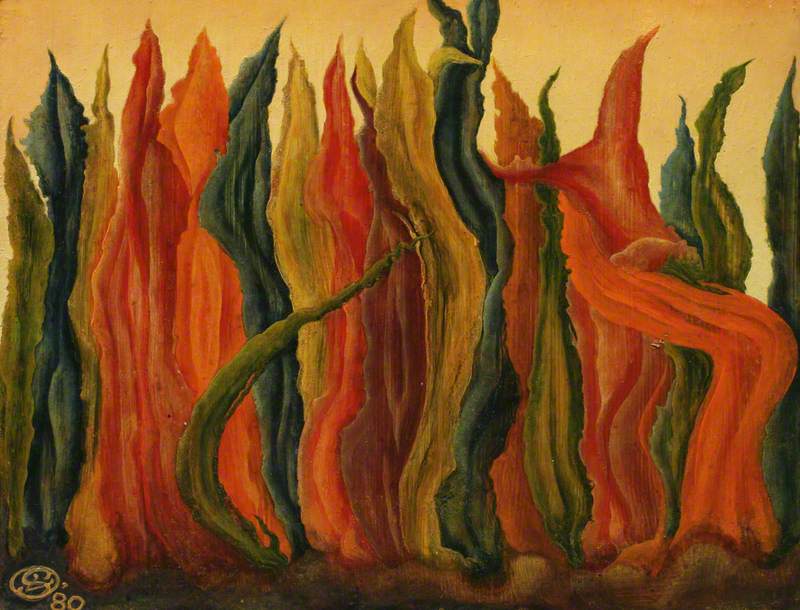

A full nine years after her official split with the British Surrealists, a period that included a terrible marriage and its aftermath, we see the brilliant theoretical integration of Colquhoun's esotericism and her Surrealism. In her 1949 essay The Mantic Stain, the first essay on Surrealist automatism in English, she detailed the divinatory and elemental aspects of automatic techniques. For example, fumage, which involves developing images from flame markings, corresponded to fire. Decalcomania, where paint is applied to a surface and then another surface is placed on top to create shape and texture, corresponded to earth.

It may be that Colquhoun's own esoteric automatism burned the brightest in her final decade of life, with her 1977 Taro Deck ('Taro' was her preferred, more archaic, spelling) and the Decad of Intelligence (1978–1979), her visual study of the sephiroth of the Kabbalistic Tree of Life. These immensely occult works, designed for contemplation, employed carefully crafted Kabbalistic colour schemes, yet the application of enamel on the paper was, to quote André Breton, 'pure psychic automatism'. The result was designed to give the viewer direct access to other dimensions through an encounter with the spirits of colour.

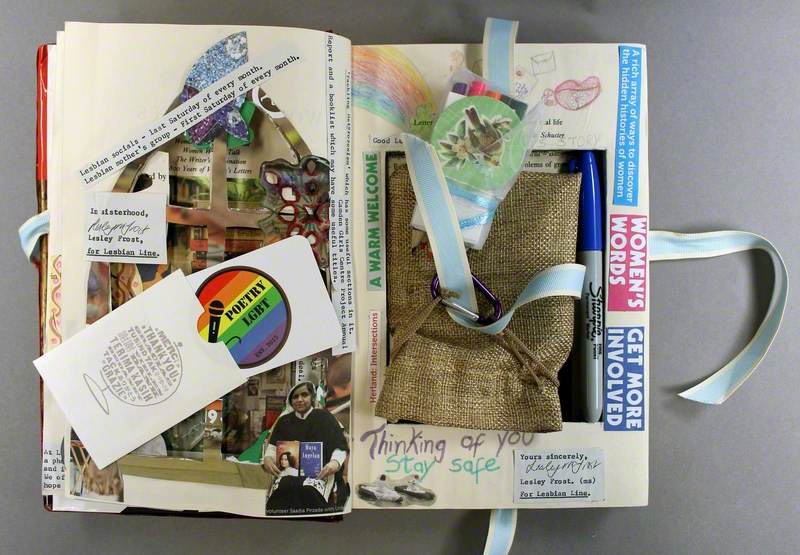

Colquhoun's work was never really 'lost', but the scope of her brilliance and the all-encompassing nature of her esoteric project was perhaps poorly understood, having been partially occluded by a focus on her relatively short official relationship with British Surrealism. The turning point came in 2009 with the 'Dark Monarch' exhibition at Tate St Ives, an exploration of esotericism in British art. Colquhoun's occult book collection was displayed there as both influence and installation. Since then, Colquhoun's magic, her occulted automatism and her relationship with sacred landscape have influenced the work of other women artists such Linder and New Zealand-based Mary MacGregor-Reid, both of whom have experienced deep connections with Colquhoun's artistic processes as well as her uncompromising dedication to recentring women's experiences and the female gaze.

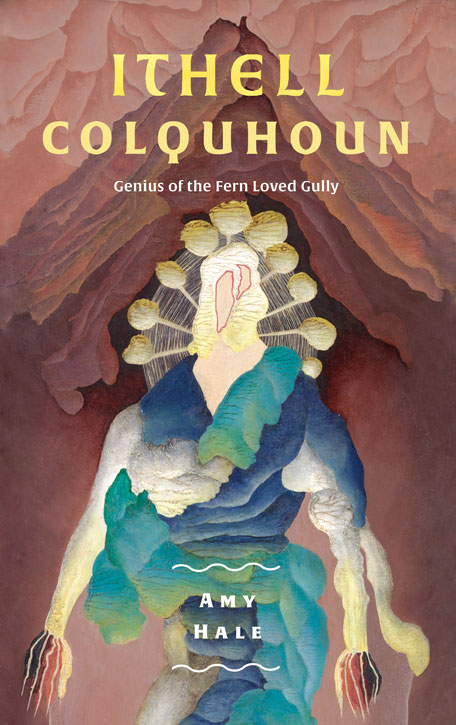

Ithell Colquhoun: Genius of The Fern Loved Gully

2020, front cover of book by Amy Hale, published by Strange Attractor Press

Set against a background of a general cultural longing for enchantment, the relationship between art and occult practice is gaining a new sense of legitimacy, and it is the flowering of esoteric art as a respectable category that is supporting the rediscovery of Colquhoun and her work. While Colquhoun resolutely considered herself to be a truly authentic Surrealist, we may find even more fruitful connections with visionary artists such as Hilma Af Klint, early twentieth-century Dutch Theosophist Olga Fröbe-Kapteyn and the Swiss artist Emma Kunz whose geometric abstractions were explicitly designed to connect the viewer with the spiritual realms that exist beyond representation, realms with which Colquhoun was most familiar.

Amy Hale, anthropologist, folklorist and author of a forthcoming biography of Ithell Colquhoun, published by Strange Attractor Press