In the ninth century BC, one woman ruled an empire that stretched from the Mediterranean coast in Syria to present-day Western Iran. Her name was Sammu-ramat, 'High Heaven'. The Greeks referred to her as Semiramis, 'the most renowned woman of whom we have any record': a commander of armies, a skilled warrior, a builder of monuments.

Great Semiramis, Queen of Assyria

c.1905, oil on canvas by Cesare Saccaggi (1868–1934)

Semiramis was an exceptional figure, the only woman to rule the Assyrian empire. And yet, through time, in art and literature, the focus shifted from the power she wielded to her love stories: in the Christian tradition, she was cast as the archetypal seductress. From Dante, who placed her in the Circle of Lust in his Inferno, to French writer Voltaire's tragedy which inspired Rossini's opera, Semiramis embodies the fate that often befalls powerful women from history: no matter how valiant, how influential they have been, they are destined to either be forgotten or vilified. And Semiramis, condemned for her 'burning desire' and 'sensual vices', falls into the second category.

The myth of Semiramis, as well as the history behind the real figure Sammu-ramat, were the inspiration behind my novel Babylonia, which follows the rise to power of Semiramis, from orphan to governor's wife to the only female ruler of the Assyrian empire. Part historical fiction, part myth retelling, the novel focuses on the infamous love triangle that eventually made Semiramis queen and reclaims the reputation of this incredible woman. Heavily inspired by Mesopotamian literature, including the Epic of Gilgamesh, the story is about female ambition and desire, love in the face of loss, and the quest for fame and immortality.

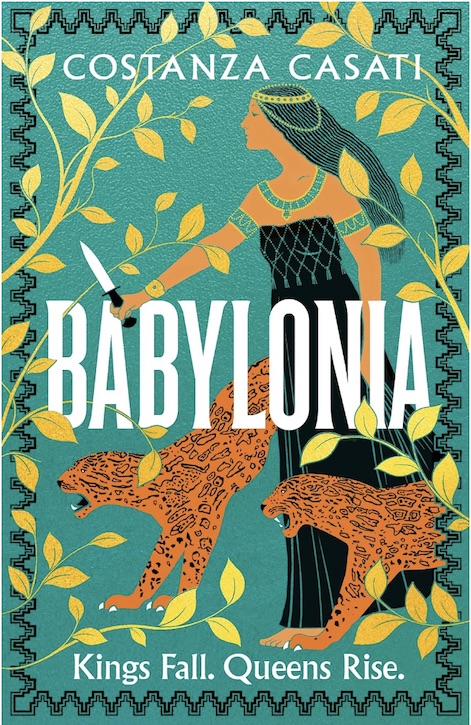

Babylonia

Costanza Casati (2024)

Not much is known of Sammu-ramat's reign. It seems like a cruel joke: for a woman who fought so hard to be remembered, history still did its best to erase her. Evidence comes from a few artefacts: statues dedicated to the Babylonian god Nabu that mention her name in the ancient city of Nimrud; an inscription in Turkey that alludes to a campaign she led with her son; a stele from the city of Ashur that reads, 'Sammu-ramat, Queen of Shamshi-Adad, King of the Universe, King of Assyria; Mother of Adad-nirari, King of the Universe, King of Assyria'. This type of mention was unprecedented for a woman in the very patriarchal world of ancient Assyria and proof that Sammu-ramat must have been a dominant political figure in the empire. She was married to Shamshi-Adad V, who had taken the throne after crushing a six-year rebellion led by his brother, and, when Shamshi-Adad died in 811 BC, Semiramis took the throne for herself.

From here, the story becomes legend. Ancient Greek historian Herodotus was the first author to use the Greek form of her name, Semiramis, and credited her with building embankments for the river Euphrates. Then, Ctesias of Cnidus, a Greek physician at the court of a Persian king, wrote in detail about a woman who rose from humble beginnings to rule one of the biggest empires the world had ever seen. Ctesias' work is largely lost, but another Greek author, Diodorus Siculus, used Ctesias' writing as inspiration for his own version of the legend in his universal history, Bibliotheca historica.

Semiramis Building Babylon

1861, oil on canvas by Edgar Degas (1834–1917)

According to Diodorus, Semiramis was an orphan born in the outskirts of the empire. Her mother, a goddess named Derceto, killed herself when Semiramis was a child, throwing herself into a lake, where she was transformed into a mermaid. Left alone on a rock, the baby Semiramis survived against all odds, cared for by doves and then by a shepherd. When she came of age, a woman 'of surpassing beauty', she caught the attention of the royal governor of the province of Syria, a man named Onnes. Onnes fell in love with Semiramis, married her and took her with him to the Assyrian capital, where Semiramis thrived, quickly learning the game of power.

Here, the story takes a turn for the worse: the king of Assyria, Ninus, became infatuated with Semiramis, marvelling at her skill and acumen. He tried to persuade Onnes to give him his wife of his own accord and, when Onnes refused, Ninus threatened him. Desperate and madly in love with his wife, Onnes grew mad and killed himself. 'Such, then,' Diodorus writes, 'were the circumstances whereby Semiramis attained the position of queen.' Semiramis gave Ninus a son, Ninyas, and shortly after, Ninus died, leaving Semiramis as queen. Here, legend and history converge: Semiramis took the throne and acted as regent until her son came of age.

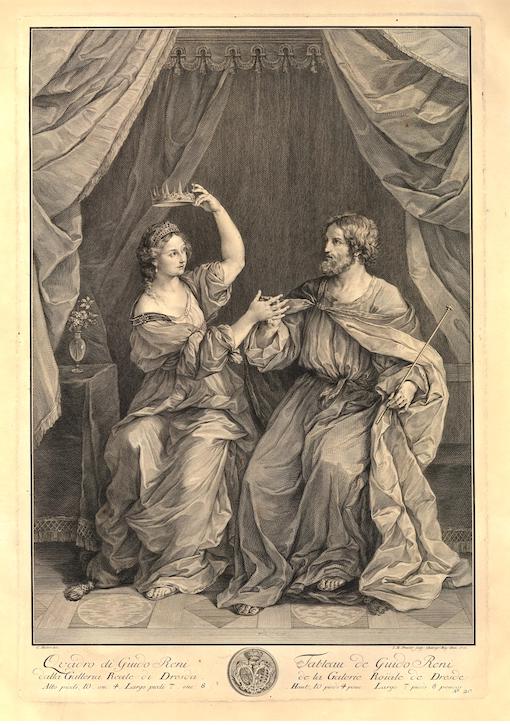

The marriage of Semiramis and Ninus is portrayed in a painting by Guido Reni (1575–1642), in which we see Semiramis placing her husband's crown on her head. This print from the British Museum is after Reni's painting, which was destroyed during the Second World War.

According to Diodorus, Semiramis persuaded Ninus to give her power for five days only, to see how well she could manage it. As soon as the crown was placed upon her head, she had him executed for good.

In another depiction, a mosaic recently discovered in the ruins of a House of Daphne in Antioch – once the third largest city in the Roman empire and capital of the Roman province of Syria – a man, presumably Ninus, sits on his bed while a woman, Semiramis, stands by his side, offering him a cup. The house was decorated with mosaics representing some of the owner's favourite scenes from the myths and legends, which means that Semiramis' story was also known in Roman times.

Mosaic pavement: Ninus and Semiramis

c.200 AD, stone, Roman

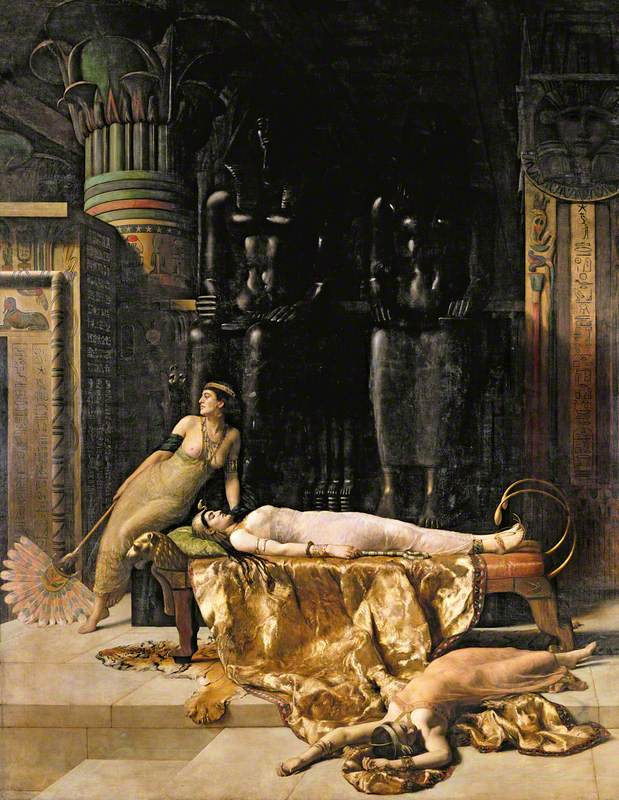

Greeks and Romans weren't the only ones to spread the myth of Semiramis. Early medieval author Moses of Chorene (c.410–419 AD), in his History of Armenia, recounts the legend of Semiramis and Armenian king Ara the Handsome. Semiramis, described by the author as 'promiscuous' and 'driven insane by love', fell in love with Ara and wished to marry him. She sent courtiers with gifts to woo him, and offered her hand in marriage, but he rejected her. Angry and heartbroken, she declared war against Armenia. Despite her order to capture Ara alive, he was slain during the battle. She kept his corpse – she is shown staring at it in a work by Vardges Sureniants (1860–1921) – and lied to the Armenians, telling them that her gods had brought him back to life. So the war was ended.

Semiramis staring at the corpse of Ara the Beautiful

1899, oil on canvas by Vardges Sureniantes (1860–1921)

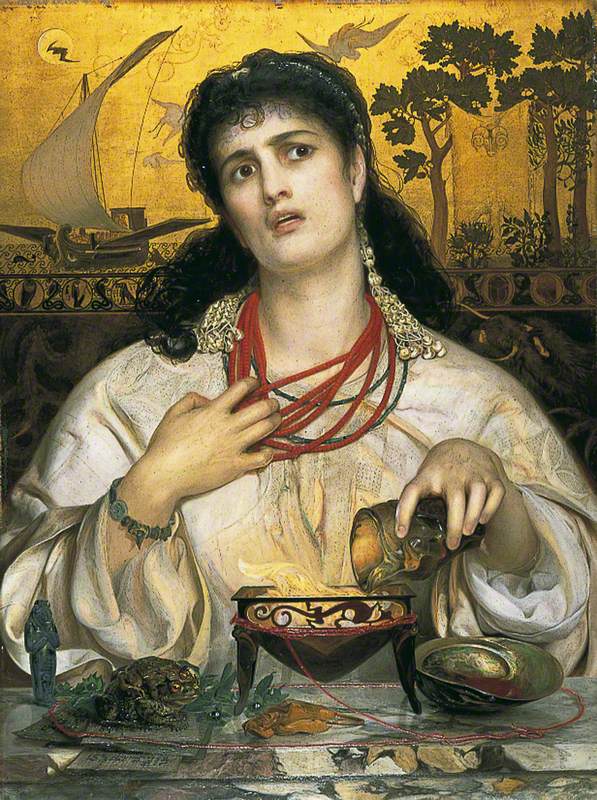

Unsurprisingly, the focus of the Armenian legend is on Semiramis' sexual desire. Diodorus himself, in his account, writes that once Semiramis became queen, she took a series of lovers from the most handsome men in her army, refusing to marry as she didn't want to submit to another man. She would sleep with them in the night and then have them executed at first light. Because of these versions of her story, Semiramis, throughout literature, has become associated with the allegorical Babylon – a symbolic place of lust and evil.

Babylonia is referenced many times in the Bible. With its Hanging Gardens and Tower of Babel, it has become a symbol of luxury, arrogance and dissolute power. Famous accounts of Babylon in the Bible include the story of the Tower of Babel: according to the Old Testament, when humans tried to build a tower to reach the heavens, God punished them by destroying the tower and making them speak many different languages so they could no longer understand each other. Babel was the epitome of chaos, and so was Semiramis, in the Christian literary tradition: a threat to the status quo, a challenge to be eliminated.

The Building of the Tower of Babel

c.1600

Marten van Valckenborch I (1534–1612)

Though Semiramis' name is not mentioned in the Bible, later Christian authors have claimed that she is, as connected with Nimrod. In his nineteenth-century book The Two Babylons, Christian minister Alexander Hislop claimed that Semiramis was the wife of king Nimrod and 'the whore of Babylon', from the Book of Revelation.

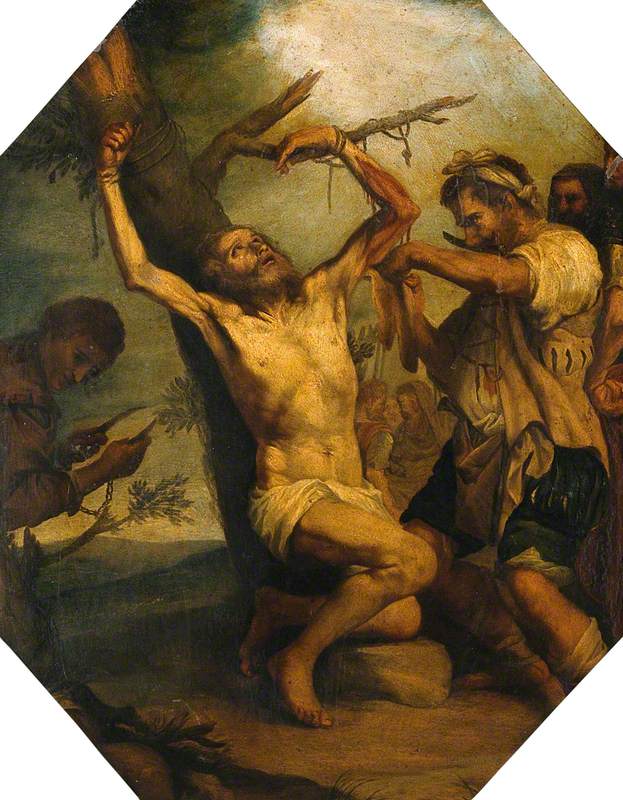

This depiction of Semiramis as a lustful seductress prevailed for centuries. Italian poet Petrarch, in his 'Triumph of Love', called Semiramis' love 'distorted' and 'unlawful': 'here are other three whose love was evil: Semiramis, Byblis and Myrrha are oppressed with shame for their unlawful and distorted love.' Dante, in his Inferno, places Semiramis in the Circle of Lust, next to Dido, Helen and Cleopatra: 'To sensual vices she was so abandoned, That lustful she made licit in her law, To remove the blame to which she had been led.'

Semiramis in Dante's Inferno

19th C, oil on canvas by José María Casado del Alisal (1830/1832–1886)

Fourteenth-century Italian author Giovanni Boccaccio wrote about Semiramis in De Mulieribus Claris (On Famous Women). He called her 'skilled' and 'spirited', praised her courage and intelligence, and even mentioned an anecdote of Semiramis going to war and leaving her beauty routine aside: 'her hair was only half combed when the news that Babylon had rebelled was brought to her. This so angered her that she threw aside her comb and immediately abandoned her womanly pursuits.' This scene has been depicted by various painters in Western art, including Pietro da Cortona (1596–1669), Matteo Rosselli (1578–1650) and Guercino (1591–1666).

In these artworks, Semiramis, an Assyrian woman, is painted to conform to European beauty standards. In Guercino's depictions, she is dressed in early modern European clothing, her maid holding a hair comb behind her, as she is interrupted by a messenger who brings her news from Babylon.

Semiramis Receiving the News of the Fall of Babylon

c.1645

Guercino (1591–1666)

In Cortona's painting, she is blonde, wrapped in a white and golden dress, against a background of classical architecture filled with antiquarian details. Staring at the sky, she takes a solemn oath to abandon her beauty routine until the war is won.

In an engraving based on the painting by Rosselli, Semiramis runs with her hair unbound, maids hurrying behind her with a helmet. Here, the queen is portrayed with a sword in hand, showing that she herself engaged in warfare, as both historical and mythical sources suggest.

I relied heavily on these sources to explore Semiramis' military skills in my novel Babylonia, focusing on a key episode that Diodorus recounts in his account of the queen's life. According to the historian, during a campaign against the land of Bactria, the Assyrian siege of the capital, Balkh, was proving endless, and so Onnes sent for his wife. Semiramis arrived and quickly realised that the acropolis of Balkh, because of its strong, apparently impregnable position, was not properly defended. So she took with her a group of soldiers accustomed to climbing rocky heights and made her way up a steep ravine, seizing the acropolis and giving a signal to the soldiers fighting in the plain.

This episode isn't the only one where Semiramis proves her exceptional skill. Once she became queen, she steadily acquired greater power through military conquests – it has been noted by many historians that Diodorus' account of her campaign against India even resembles the one of Alexander the Great.

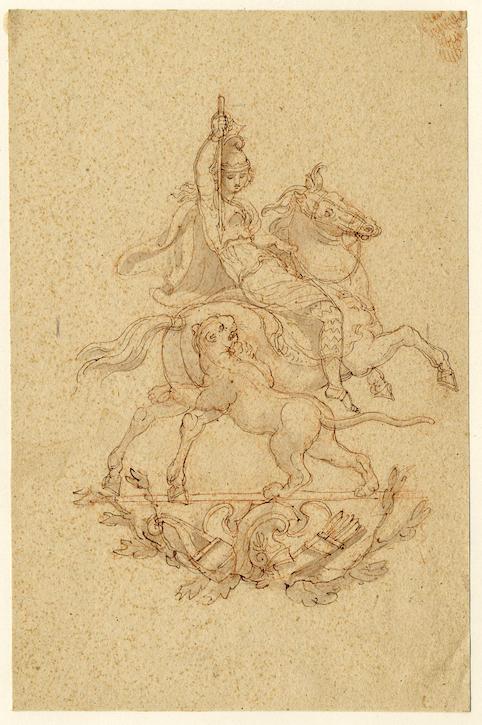

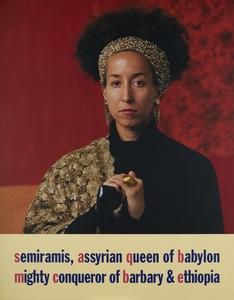

She is often depicted hunting lions – a brutal form of entertainment in the Assyrian empire, where kings killed lions in an arena while everyone watched and cheered – and is one of the 'Heroines of Antiquity' from the Amberley Castle, a series of painted medieval panels depicting great warriors and leaders from ancient history carrying weapons: from Zenobia, queen of Palmyra, to Lampedo, Amazon queen. The panels, a celebration of the power of women, were commissioned by the Bishop of Chichester to dissuade Henry VIII from divorcing his first wife.

Semiramis

(from the Amberley Castle 'Heroines of Antiquity') (Amberley Queens) c.1526

Lambert Barnard (c.1490–1567)

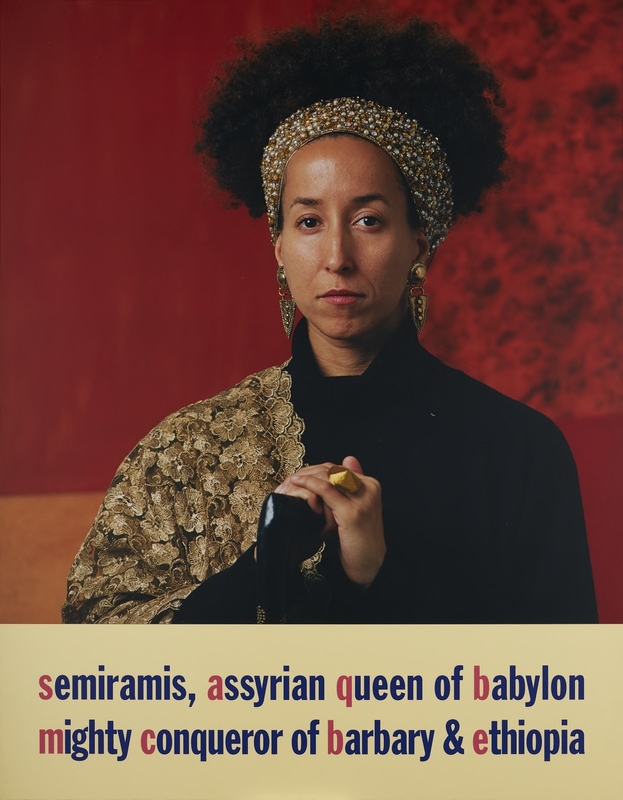

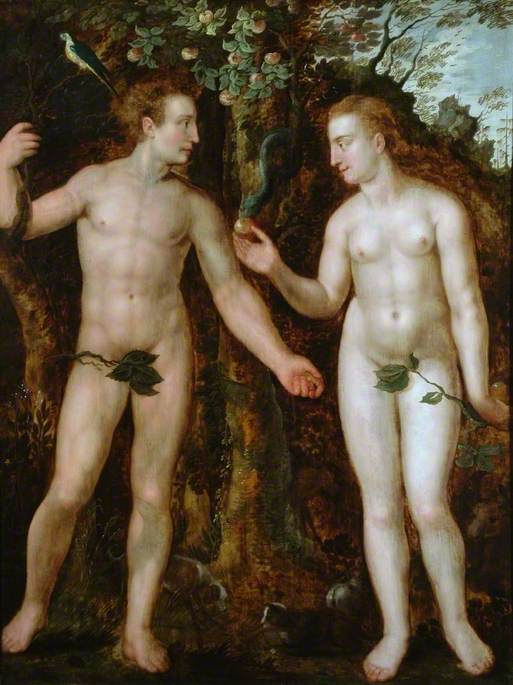

While the women in the Amberley Panels have European features, contemporary artist Joy Gregory (b.1959) shot a series of portraits inspired by the panels, featuring women who reflected how these queens might have actually looked, highlighting physical traits common to the geographical region from which they were thought to originate.

The legacy of Semiramis is contradictory. On the one side, the Christian tradition has condemned her as a lustful, treacherous seductress. On the other, her military power and commanding skills were so exceptional that artists couldn't help but highlight them in their depictions.

From a rags-to-riches story to the femme fatale cliché, Semiramis' myth encompasses many literary tropes – to find the real woman within, we have to peel back all the layers that have shrouded her legend in darkness. As Italian author Michela Murgia once said, 'Men's stories are torches, passed from hand to hand and thus surviving into eternity. Women's, on the other hand, are little lamps, lit and extinguished in the darkness, if there is no one to carry their light.' No matter the legends that have been spun around her, Semiramis' memory refuses to fade – a light that burns as bright as the greatest fires.

Costanza Casati, writer and author of Babylonia (Penguin Books)

This content was funded by the Samuel H. Kress Foundation