It is now eleven years since Craigie Aitchison (1926–2009) died, and his star rides as high as ever. Remembered with great love and affection by his friends, his work continues to be celebrated and admired in this country and abroad.

© the artist's estate / Bridgeman Images. Image credit: Arts Council Collection, Southbank Centre, London

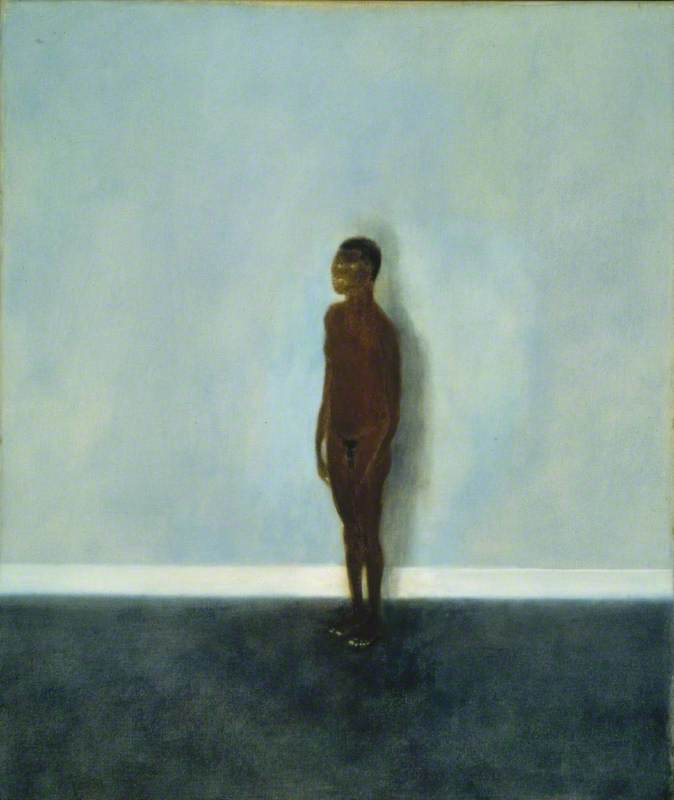

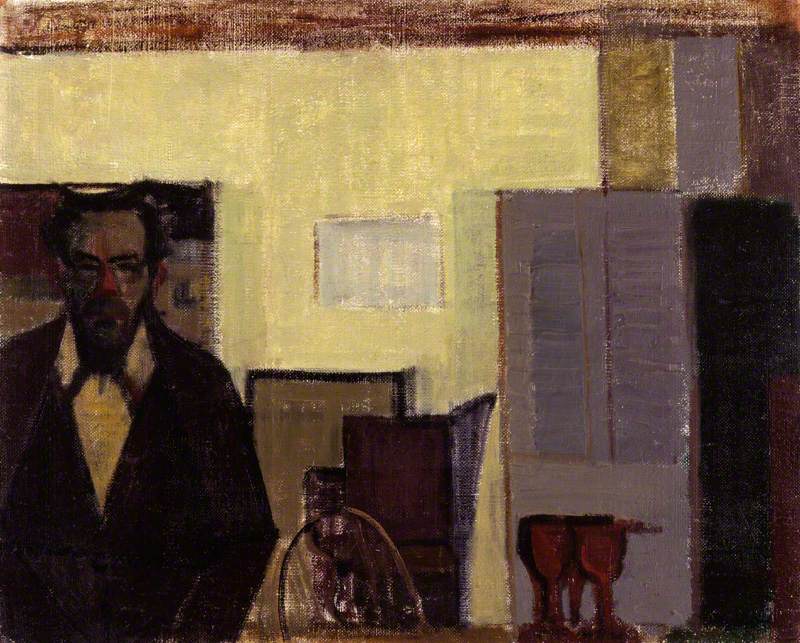

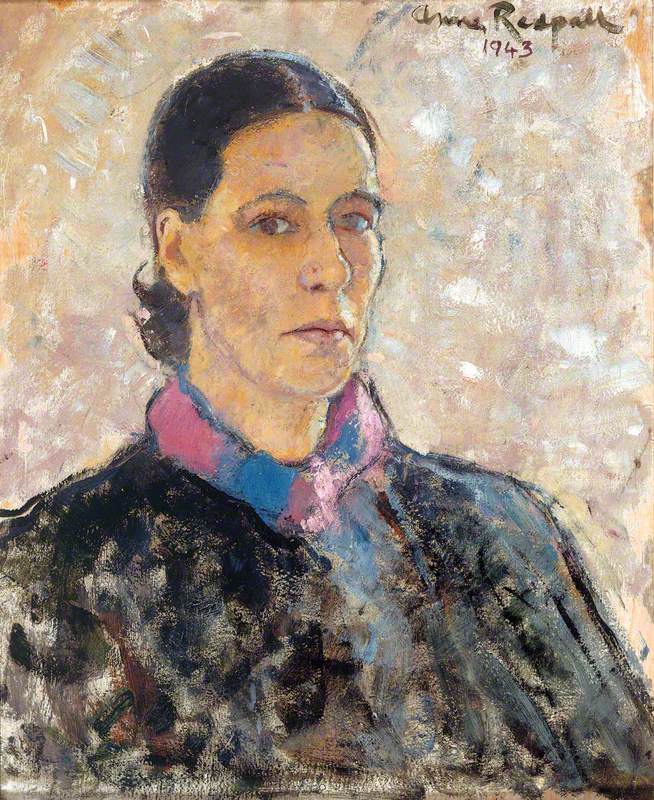

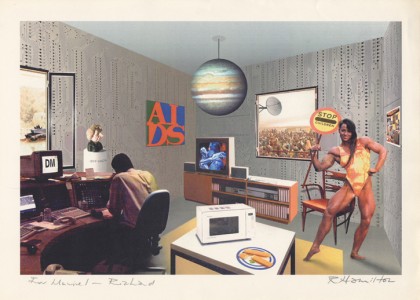

Craigie Ronald John Aitchison (1926–2009)

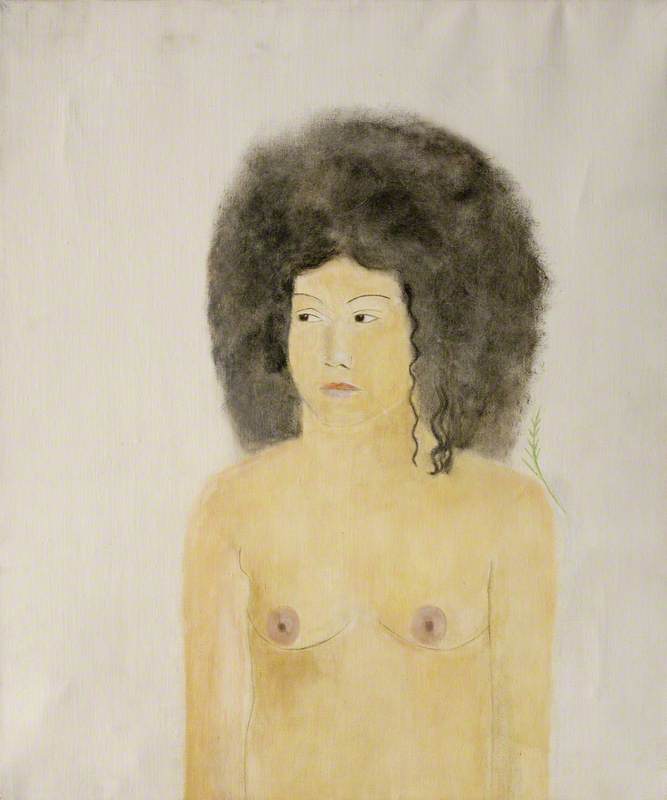

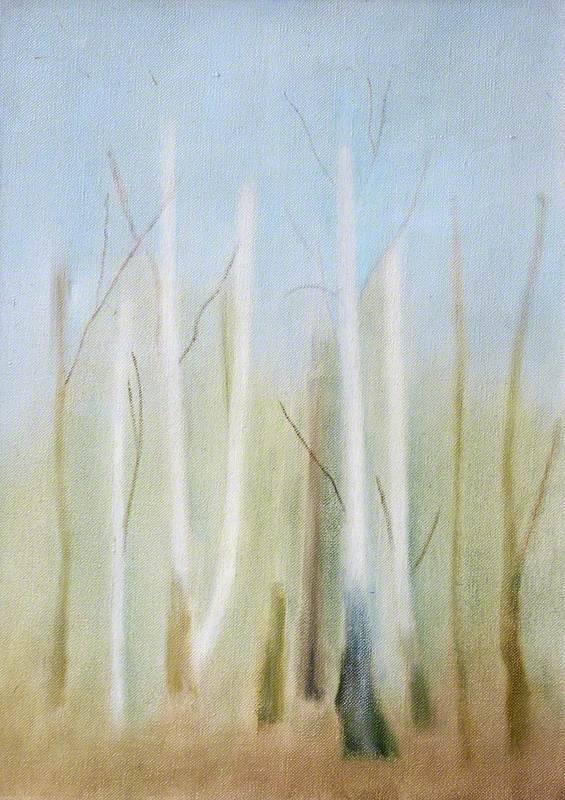

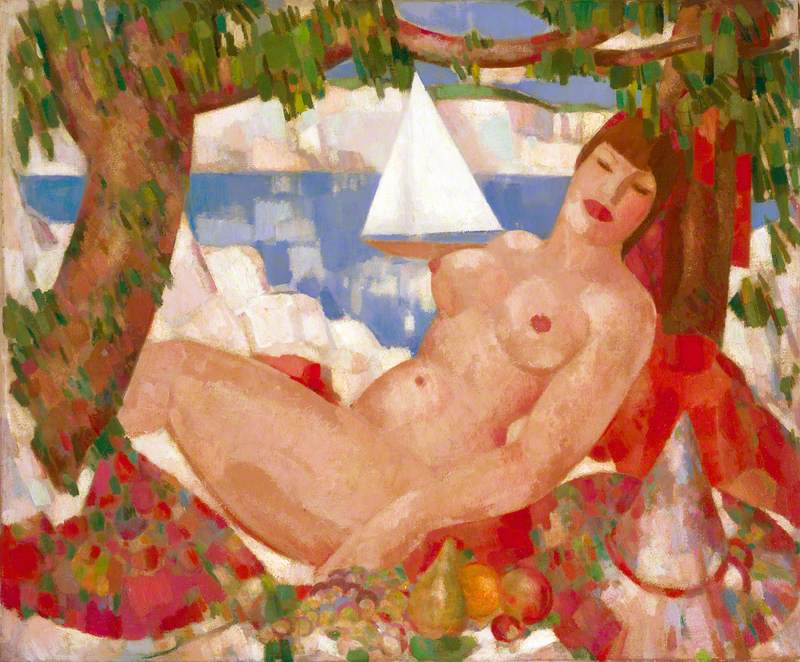

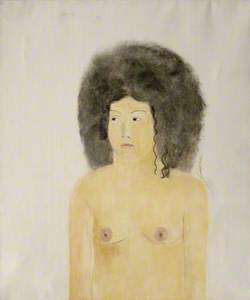

Arts Council Collection, Southbank CentreAlthough Scottish by birth, Aitchison moved to London in 1963, and thereafter divided his time between his terraced house in Lambeth and a second home in Italy, outside Siena. He painted still-life subjects, religious pictures, portraits and nudes, landscapes and his dogs. His preferred models tended to be West Indian or African because he loved the way other colours looked next to warm skin tones.

The first painting by Aitchison to enter a UK public collection was Model Standing Against a Blue Wall (1962), when it was bought by the Tate from the Beaux Arts Gallery in 1964.

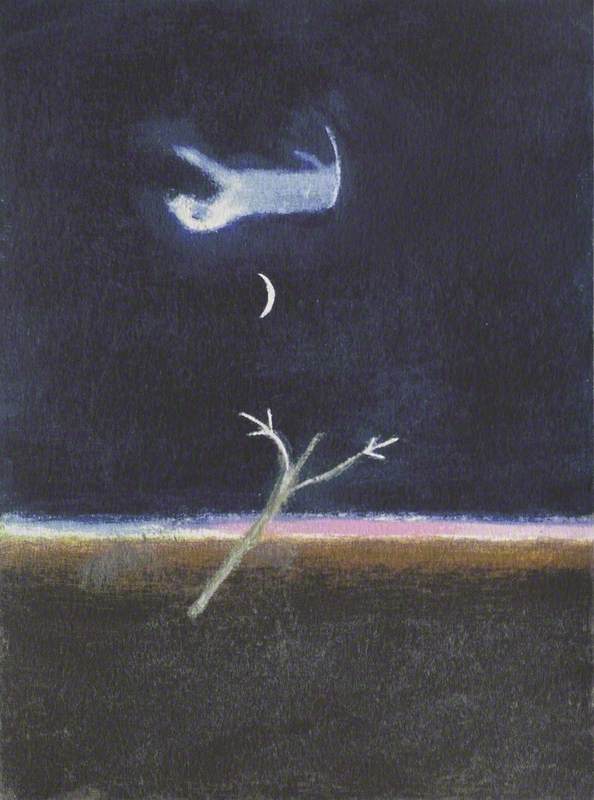

Another painting of the same period, Nude Standing in Front of a Picture (1963), in Nottingham Castle Museum, is almost better value, as you get a Crucifixion in the background as well as the foreground nude. The resulting interplay of organic shapes against the geometry of wall, floor and framed picture – like a doorway to the outside world in which the Crucifixion is actually taking place – is very moving.

© the artist's estate / Bridgeman Images. Image credit: Nottingham City Museums & Galleries

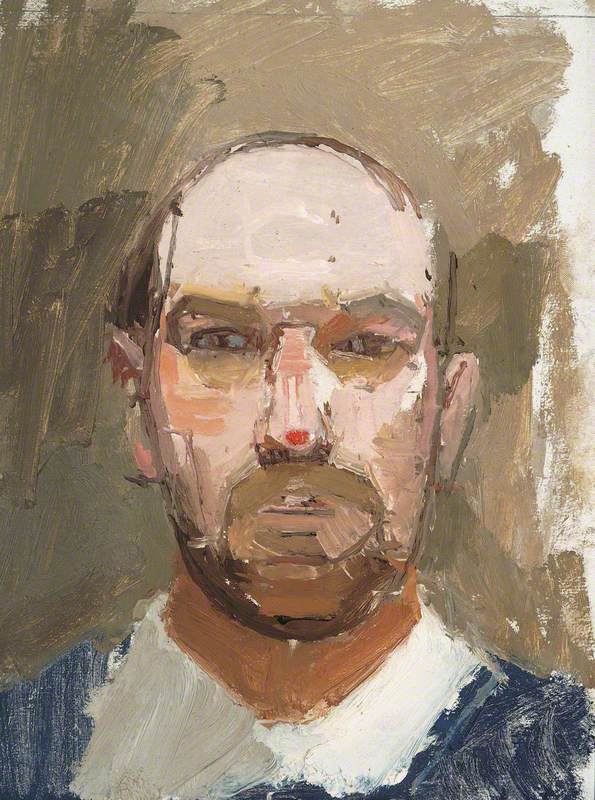

Nude Standing in front of a Picture 1963

Craigie Ronald John Aitchison (1926–2009)

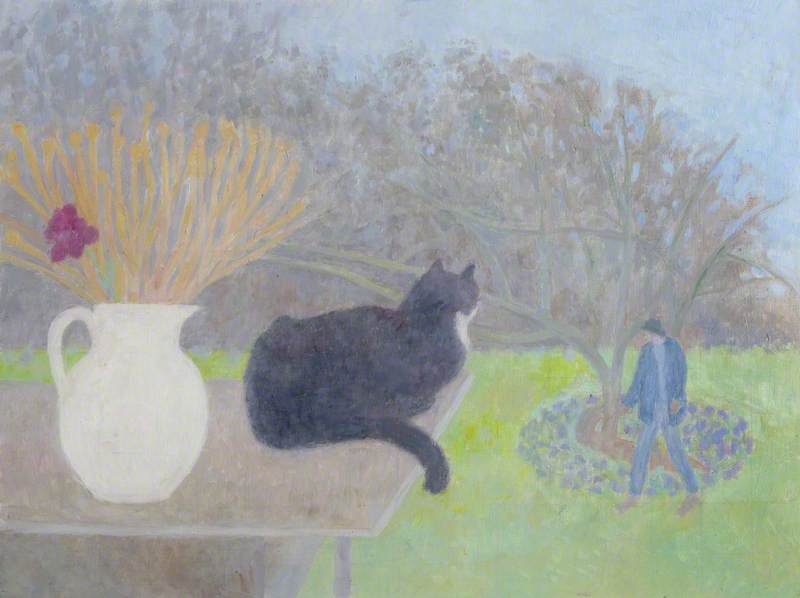

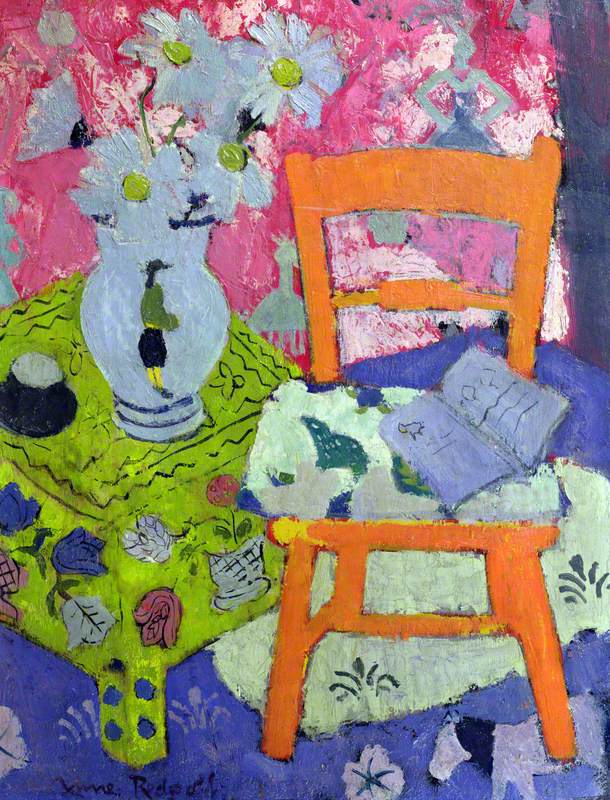

Nottingham City Museums & GalleriesSome of Aitchison's most popular paintings have been of objects he lived with: a tea caddy or a candlestick, a cup or a vase (mostly with flowers in it), a cellophane-wrapped Italian Easter egg or a handful of liquorice allsorts.

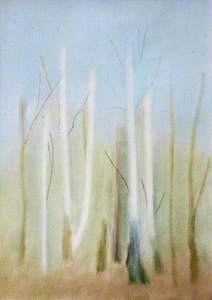

Still-Life (1975), in the Government Art Collection, is a less well-known image, with an unusual format. Tall and thin, it is composed of a vibrant arrangement of stripes, a vase, flowers and a canary. It dates from the period when Aitchison kept canaries and allowed them to fly free in his studio. They were so at home that they made a nest in an old mattress leaning against a wall, and successfully reared a family.

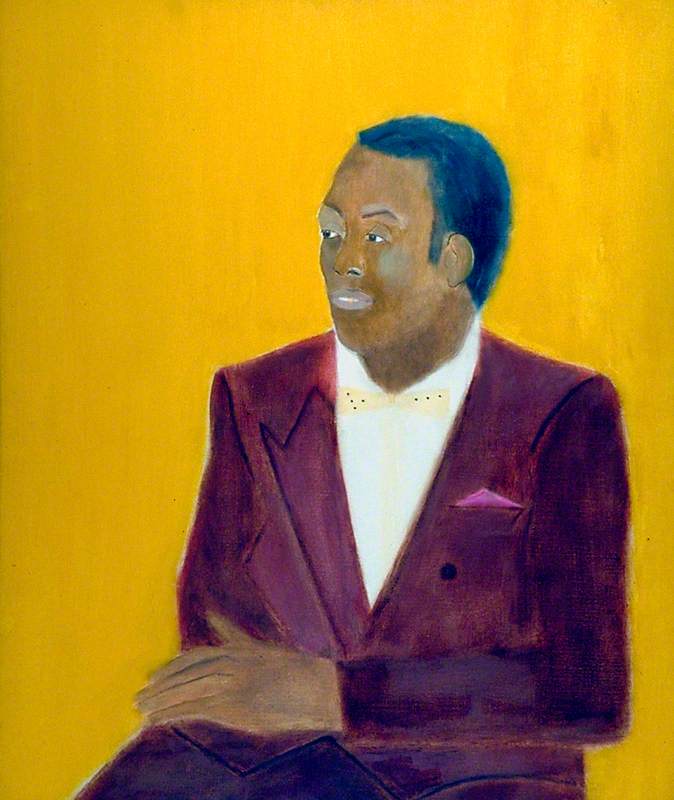

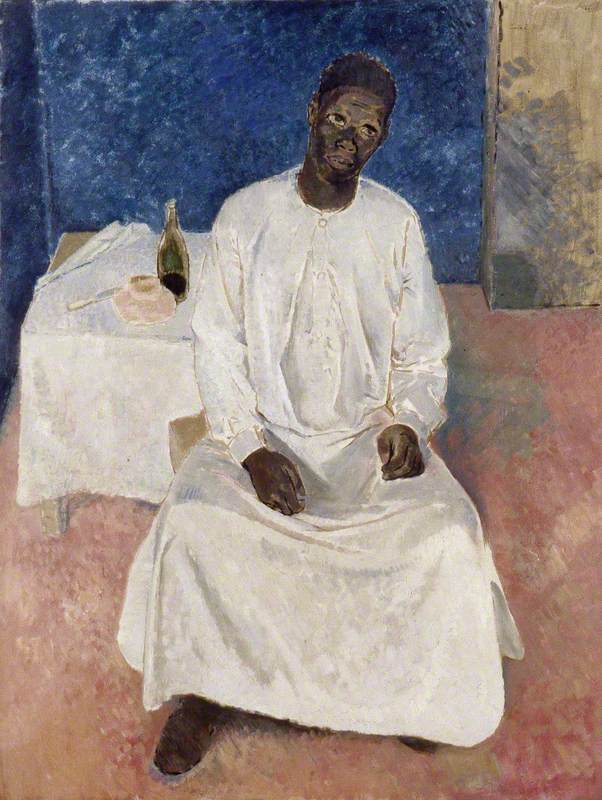

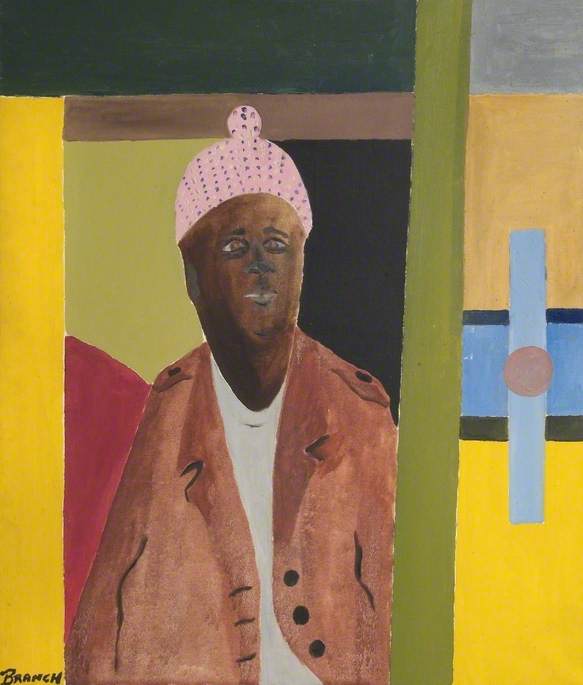

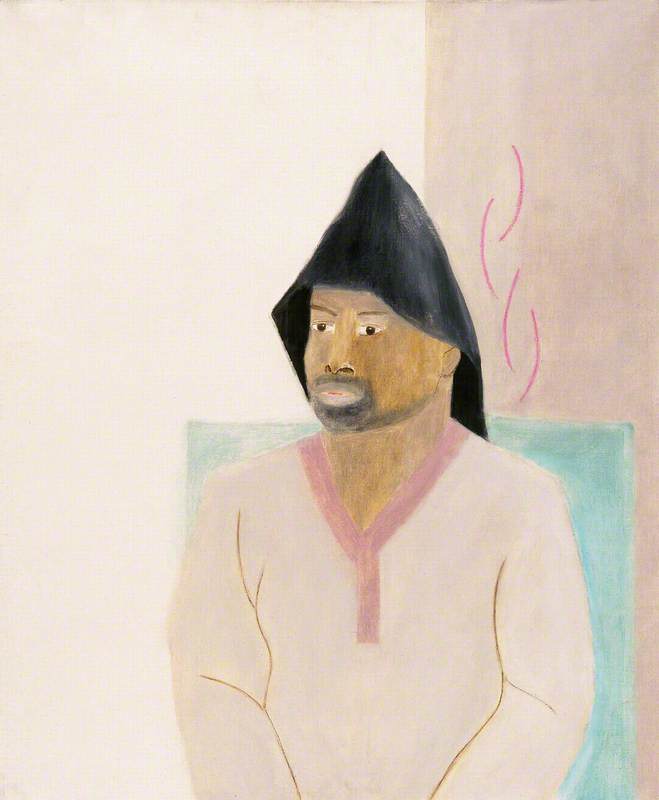

If Aitchison found a good model, he would paint him or her repeatedly, and his all-time favourite was Georgeous Macaulay. He is the nude in Tate's 1962 painting (discussed above), and was the subject of three others in Aitchison's 1964 exhibition. A decade later, he was still painting him, as Georgeous Macaulay in a Sou'wester (1976), in the National Museum of Wales, Cardiff, attests.

© the artist's estate / Bridgeman Images. Image credit: Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales

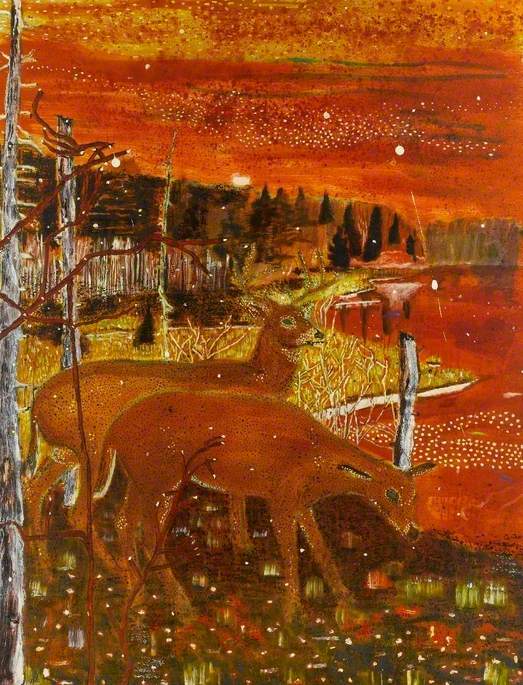

Georgeous Macaulay in a Sou'wester 1976

Craigie Ronald John Aitchison (1926–2009)

Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum WalesAitchison was always intrigued by unusual headgear, principally because of the resulting shapes which could become the focus of a painting. Here it is the sou'wester hat, looking a bit like the upturned head of a shark, that dominates. The delicate pink decorative curves, which pick up on the lines articulating the sleeves of the sitter's shirt, and the pale turquoise oblong behind the figure, offer a telling contrast to the pointed hood.

The placement of each element is pitch-perfect: as Craigie always said, it was just a matter of 'getting it right'. He would paint and re-paint a picture to achieve this, using thin paint rubbed into the canvas, simplifying his compositions with breathtaking rigour.

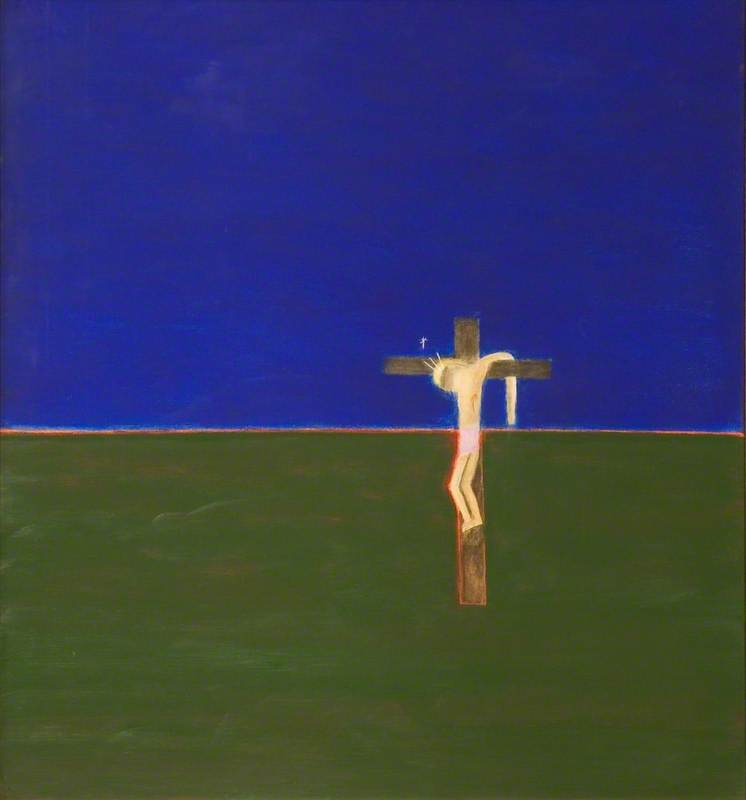

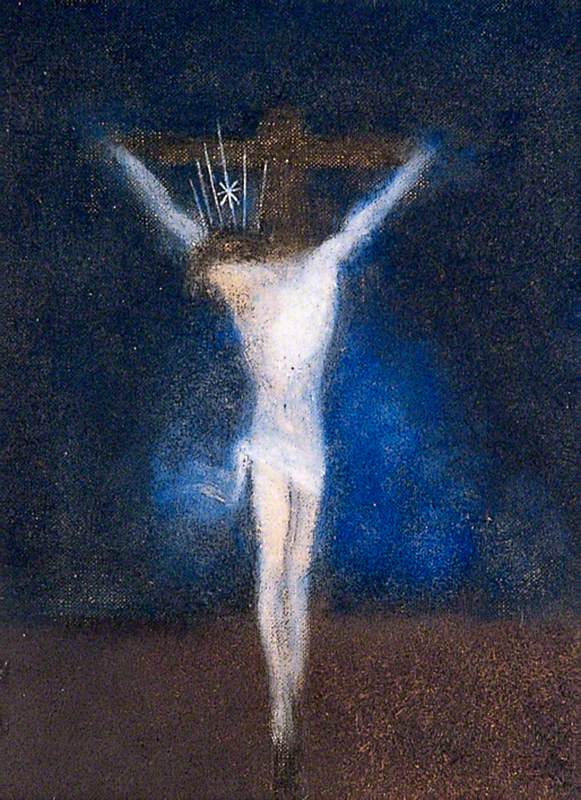

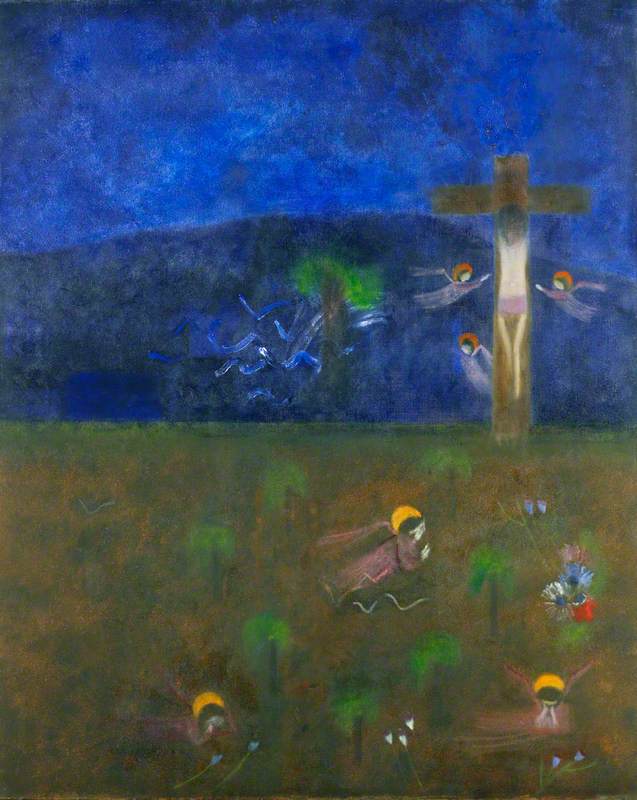

There are several of his Crucifixions in public collections, but one of the most memorable is in Birmingham, dating from 1984–1986. A large canvas, as many of Aitchison's late Crucifixions are, it depicts Christ on the cross, but without any arms.

Aitchison was quite prepared to take liberties with human anatomy if it helped him to make the image more powerful, and his Christ figures sometimes have only one arm or one leg. (As he once replied to an interviewer who asked him why he did this: 'Not everyone is lucky enough to be born with two arms and two legs'.)

Here the pared-down simplicity of the image increases the drama, already enhanced by the golden halo, and made more poignant by the inclusion of the bird and the dog as witnesses and mourners. Aitchison himself was not especially religious, but he recognised the Crucifixion as one of the greatest of human events and painted it repeatedly throughout his career.

An early influence on him was Salvador Dalí's painting Christ of St John of the Cross in the Kelvingrove Art Gallery, which he saw there sometime after its purchase in 1952. In Dalí's painting, the crucified Christ is suspended over the bay at Port Lligat in Catalonia, Spain, and depicted as if seen from an extraordinary angle above.

Aitchison never emulated this viewpoint, but he did take inspiration from the way Dalí interpreted the Crucifixion in his own way to make a strong painting. In an interview with me in 1989, Craigie said: 'I remember going to see it and being absolutely amazed the way the cross completely went into the canvas, like an illusion. I still like that picture.'

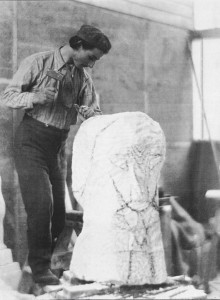

Craigie first painted a Crucifixion when he was a student at the Slade School of Fine Art, which is part of University College in London. One of the teachers said: 'It's a very serious subject and much too big a subject for you to tackle.' But that only spurred Craigie on to paint another one.

He never succumbed to adverse criticism, though he remembered it and was clearly wounded by it. Two visiting Slade tutors, Victor Pasmore and John Piper, both told him to give up painting. Thankfully he didn't. As he said, if it had been somebody he really respected, like L. S. Lowry, also a visiting teacher, he might have paid attention. But Lowry only encouraged him.

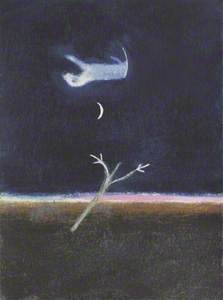

Wayney Going to Heaven (1989), in The Fleming Collection, is a portrait of the first Bedlington terrier that Aitchison owned. He bought Wayney in 1971, after discovering the breed at Crufts Dog Show, and they were inseparable until Wayney's death. Here Aitchison paints his dog upside down, floating gently off, paws first, to heaven.

It's a little like The Apotheosis of James I in the Banqueting House, Whitehall, by Peter Paul Rubens, in which the dead king ascends to heaven as a reward for his earthly labours. For the rest of his life, Aitchison kept Bedlingtons, at one time owning a terrier dynasty: grandmother, mother and daughter, all at once.

Dogs were very important to him (Craigie often said he could only trust the dogs, and that he preferred animals to people), and his luminous painting Model and Dog (1974–1975), in the Tate, is a distilled statement of this. This large composite image includes several favourite Aitchson motifs – the dog, the nude, a cross on a distant hill, butterflies and flowers – all set within a geometrical structure of bands of succinctly modulated colour.

Once again strict anatomy is eschewed, and Aitchison has painted the model with only one breast because that's what the painting needed. (He made other paintings of her with both breasts intact, looking very beautiful, and she seemingly understood Craigie's need to edit her body for the sake of the picture.)

I knew Craigie for more than 20 years and for much of that time I lived within walking distance of his studio and would visit him most weeks. In some ways a modest man, he didn't keep any of his own work (he only had posters advertising his exhibitions, which he framed but didn't hang), selling everything or giving it away.

Considering the crowded nature of his home, he was surprisingly minimalistic in his art, as well as a great colourist. He thought his intensely poetic images were quite straightforward, but they are impossible to imitate convincingly. Although they look so effortless, he himself often had trouble with them.

In another interview with me in 2004, Aitchison discussed this: 'That seems to be all that it's about – deciding. Somebody said that painting is a complete and absolute way of having to make up one's mind. Whether to put two trees instead of one, or to leave it. It's exhausting trying to make up your mind. If it wasn't like that it would just be boring to do.'

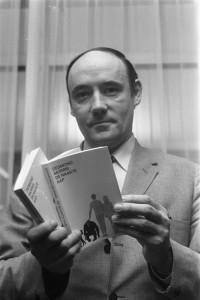

Andrew Lambirth, writer and author of Craigie Aitchison – Prints: A Catalogue Raisonné