For the Pre-Raphaelite artist Dante Gabriel Rossetti, the beautiful faces that inhabited his creative world belonged to a small number of women he elevated to the level of goddesses. His love life has become the stuff of legend, so it is unsurprising that when books and films tell Rossetti's story, they concentrate on his lovers.

To start with there was Elizabeth Siddal, talented, yet addicted to laudanum which would eventually kill her. Wrecked by grief, Rossetti turned to the wife of his best friend, Jane Morris, and in her found the muse that would carry through his art until his death in 1882. However, in the middle, present in his life for 25 years was Fanny Cornforth, by his side, in his house and on his canvases. So why is she so often minimised in, if not entirely left out of, Rossetti's story? What is our problem with Fanny, and what does it say about us?

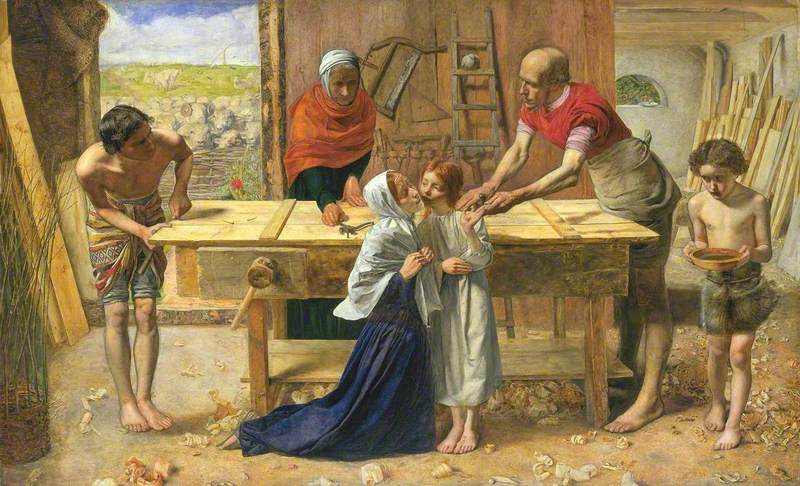

In the mid-1850s a West Sussex housemaid called Sarah Cox came to London to visit her aunt and enjoy a break from a fairly dismal existence, with most of her family having died from tuberculosis. When Rossetti accosted her at a fireworks display, he invited her to pose for Found, a work that planned to show a prostitute confronted by a country sweetheart. While an unfinished version from c.1854 can be found in Tullie House Museum and Art Gallery, the completed version belongs in Delaware Art Museum.

Found

1854–1855, 1859–1881, oil on canvas by Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–1882)

The ease in which Sarah Cox became 'Fanny' and this first poignant role formed an opinion in Rossetti's friends about what sort of girl she was, and somehow it stuck. In truth, Fanny was from a similar background to both Elizabeth Siddal and Jane Morris. However, unlike Jane and Elizabeth, there was no attempt on Fanny's part to improve her accent, education or develop artistic talent. On the contrary, the joy of Fanny was that she was uncomplicated and affectionate, remarkable in her uncompromising attachment to a man whose mental health challenges were barely acknowledged by anyone else.

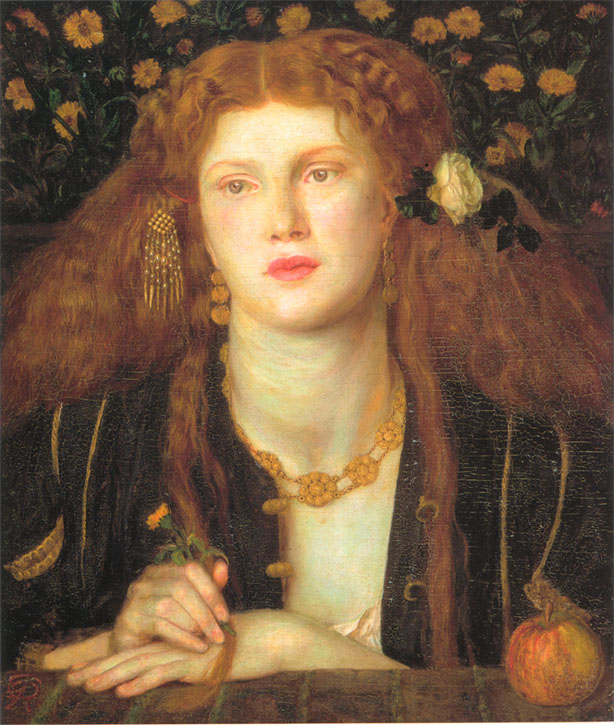

Bocca Baciata

1859, oil on panel by Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–1882)

That's not to say Fanny did not achieve anything artistic through inspiration. Arguably, Fanny is responsible for changing Rossetti's art style from watercoloured medieval scenes to aesthetic single-figure images of beautiful women in lush interiors. Rossetti left the moralising painting Found half-finished in favour of Bocca Baciata (1859) followed by Fair Rosamund (1861), Fazio's Mistress (1863), and The Blue Bower (1865), together with scores of pencil sketches of their domestic life together.

Unfortunately for Fanny, her heyday in Rossetti's art was between the untimely death of his wife, Elizabeth Siddal in 1862 and his affair with Jane Morris, which began in the later 1860s after the commission of The Blue Silk Dress (1868).

Blue Silk Dress (Jane Morris)

1868

Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–1882)

Lady Lillith

1866 (altered 1872–1873), oil on canvas by Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–1882)

The added complication was that Rossetti's chief patron in this period, Frederick Leyland, wanted a different face in his paintings, causing Rossetti to remove Fanny's face from Lady Lilith (1866–1873) and complete Venus Verticordia (1864–1868) without Fanny, replacing her on both occasions with Alexa Wilding. Interestingly, when plain old Alice Wilding changed her name to Alexa, no one batted an eyelid, but then her relationship with Rossetti was purely business and she had the good manners to keep quiet and go home at the end of the day.

Fanny's career as Rossetti's main model and muse lasted only from 1859 to 1865 but her presence in his life was inconveniently longer, lasting all the way to his death in 1882. The problem for Rossetti's friends, and then his biographers, is how to understand her role in his life. She wasn't his wife, she wasn't his muse for long and she was not seen as his intellectual or artistic equal, so why was she there?

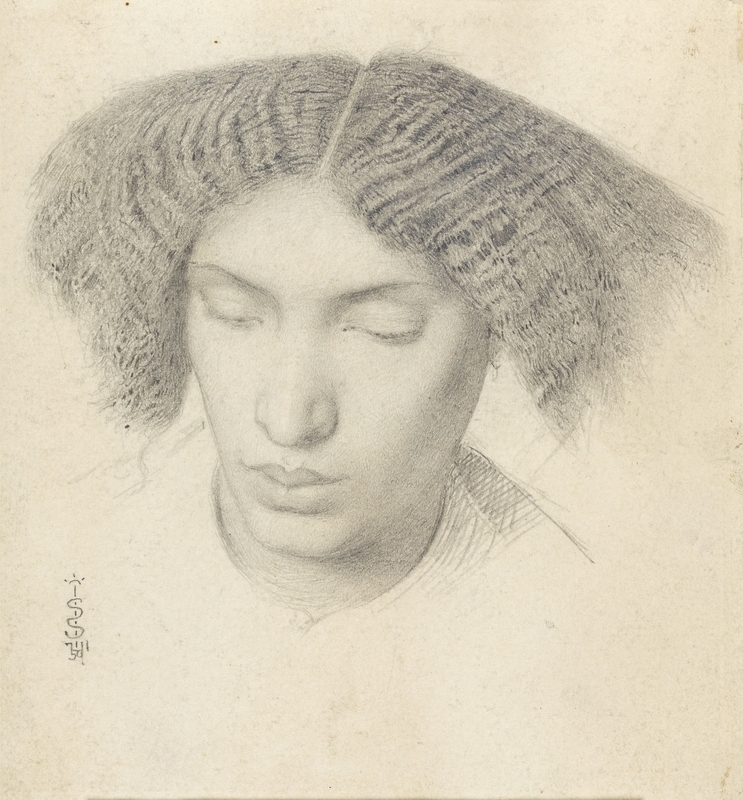

Fanny Cornforth

(study for Fair Rosamund) 1861

Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–1882)

The uncomfortable truth was that Fanny provided support and care for Rossetti's mental health and many physical problems. Fanny's presence reminded his friends and family of Rossetti's problems which were a source of shame. Jane Morris ended her relationship with Rossetti over his drug use and many friends distanced themselves from him in the years before his death, but Fanny remained at hand, unwelcome or unacknowledged by those who called themselves Rossetti's friends, and often as the mood took him, by Rossetti himself. Still, she waited for the plaintive little notes that inevitably came when Rossetti was lonely and demanded her company. And Fanny always came back to him.

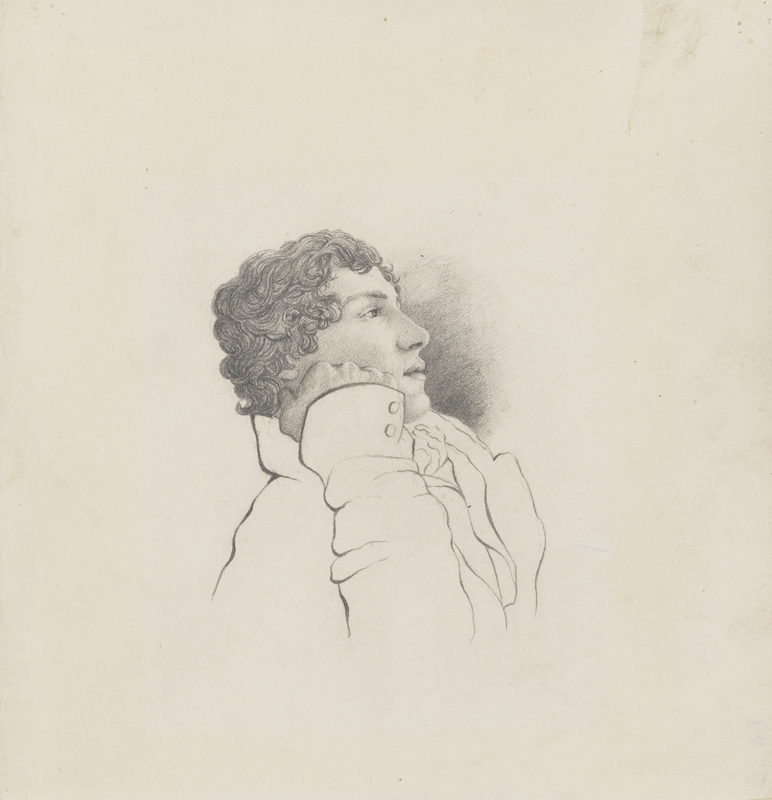

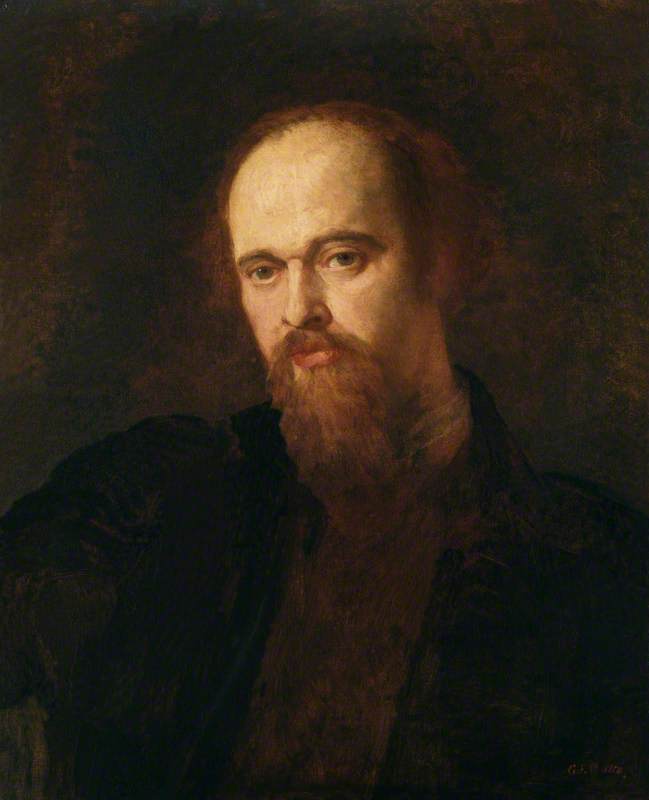

Dante Gabriel Rossetti

1870–1871

George Frederic Watts (1817–1904)

After his death in 1882, Rossetti's friends were startled to find out that Fanny had amassed a collection of his works, and she held her own tribute exhibition to her lover in the suitably named The Rossetti Gallery in Old Bond Street. Rather than believe she could have collected pictures on her own, or that she had any sense of artistic taste, Rossetti's friends and family accused her of theft, going as far as to threaten legal action over her ownership of a portrait of Rossetti by George Frederic Watts.

Fanny was able to account for every item with receipts and would go on to sell many of her precious artworks to Samuel Bancroft Jnr, an American businessman whose collection would form the Delaware Museum of Art. Even after his death, Rossetti's circle struggled to find Fanny a place, as a middle-aged, working-class woman, plump and talkative had no place in the mythologising of the great artist and his legacy.

Fanny had won her battles with Rossetti's friends and family but writers would take revenge upon her, belittling her role or leaving her out altogether in the many biographies that arrived swiftly on the heels of his death. Fanny had failed to be accepted into the society that had once admired her face and so as an old, poor woman, she found herself friendless and without understanding. She was taken to live on the south coast, then on to Graylingwell Asylum in Chichester when she was too frightened to live alone, where she died after a fall in 1909.

Fanny's afterlife was bittersweet. Starting with Violet Hunt's modern biography of Elizabeth Siddal, The Wife of Rossetti (1932), attempts have been made to find a place for her within the narrative of Rossetti's life. Unfortunately for Fanny, she has come to fulfil the trope of the tart with a heart, tempting an all-too-willing Rossetti away from Elizabeth with her ample charms, and ultimately causing the death of the talented and despondent Miss Siddal. As late as 2009's period drama Desperate Romantics, Fanny is still awkwardly caught between the two great love stories of Rossetti's life as a comedy aside, having acquired a cockney accent and the propensity to take her clothes off, often while eating.

Somehow, both contemporary and modern audiences seem unable to understand the importance of Fanny within Pre-Raphaelite art – her sturdy, stoical presence does not chime with tragic romance or glorious unending beauty. Her crimes amount to an apparent lack of talent or education, yet Rossetti's letters hint that she created some of his models' costumes and she collected an impressive range of his art. She did not die young and beautiful like Elizabeth Siddal, or fade gracefully into myth like Jane Morris. She grew old and fat, two crimes for which women are rarely forgiven.

In fact, the importance of Fanny Cornforth is that she represents a very relatable reality of female experience. The way she is spoken about in biography is worryingly reflective of how women can still be dismissed for not being perfect, beautiful and quiet. We should talk about all women with the same kindness that Fanny showed the man she loved.

Kirsty Stonell Walker, writer and researcher

Kirsty is the author of Stunner: The Fall and Rise of Fanny Cornforth (Unicorn Publishing Group)