At the close of the nineteenth century and the dawn of the twentieth, Glasgow emerged as a vibrant hub of creativity and artistic innovation. Among the key figures of this cultural revolution were talented women artists and designers known as the Glasgow Girls. These women made significant contributions to art and design, bravely pursuing careers in a field traditionally dominated by men.

At the turn of the twentieth century, Glasgow became the second city of the British Empire. By 1900, the city's rapid industrialisation, particularly in shipbuilding and locomotive manufacturing, had made it one of the wealthiest cities in the world.

This prosperity led to the rise of new affluent social classes, eager to display their status through the consumption of art and decorative arts. This environment nurtured artistic innovation, and the Glasgow School of Art became a creative centre, attracting students and teachers who influenced various artistic movements.

Who were the Glasgow Girls?

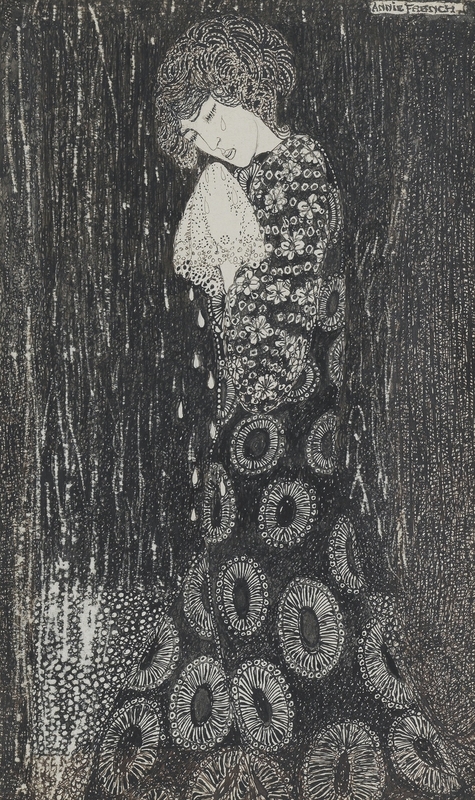

The term 'Glasgow Girls' refers to women artists and designers active between 1885 and 1914, associated with the Glasgow School of Art. Key figures include Margaret Macdonald, Jessie M. King, Frances Macdonald, Bessie MacNicol, Annie French, and Jessie Newbery. The phrase 'Glasgow Girls', a clear reference to the Glasgow Boys, was coined by William Buchanan in his catalogue for the 1968 Scottish Arts Council exhibition on the Glasgow Boys.

The artists themselves never used this term, and they were not a unified artistic movement – their styles and practices were diverse. However, they were united in their resolve to assert themselves as women artists and to improve professional opportunities for women in the arts, with some of them engaged in the Glasgow Society of Lady Artists.

Several Glasgow Girls played pivotal roles in developing the Glasgow Style (1895–1920), a distinctive Scottish form of Art Nouveau. The Macdonald sisters, Margaret and Frances, along with Jessie Newbery and Ann Macbeth, were central to this movement. Their work spanned various media, including painting, illustration, metalwork, textiles, and ceramics. They were fully recognised as artists, earning a living from their art and teaching at the Glasgow School of Art.

However, throughout the twentieth century, their contributions were overshadowed by those of male artists, such as Charles Rennie Mackintosh. For his part, Mackintosh acknowledged the brilliance of his wife and fellow artist Margaret Macdonald, stating in a letter to her, 'You are half if not three-quarters in all my architectural work.'

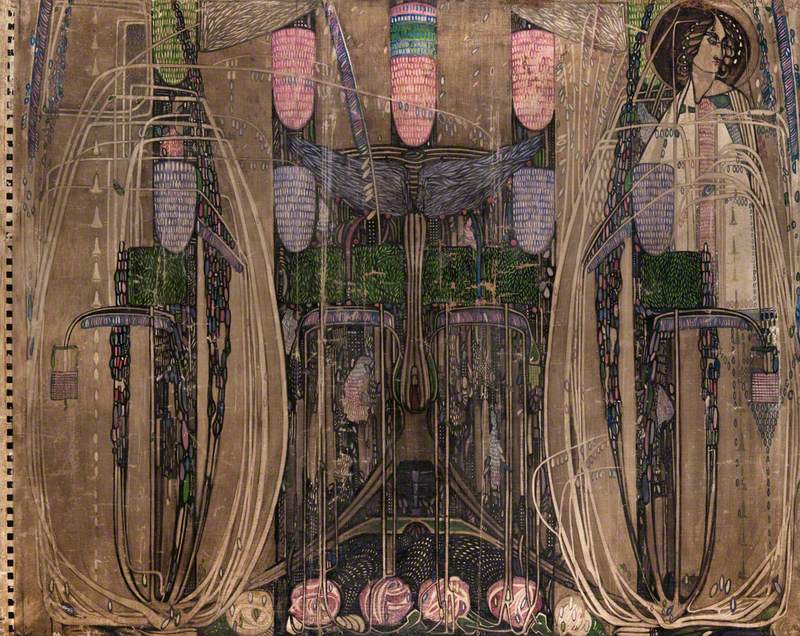

Wall Panel for the Dug-Out (Willow Tea Rooms, Glasgow)

1917

Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1868–1928)

Here we will look at three artists who were part of the Glasgow Girls.

Margaret Macdonald (1864–1933)

Margaret Macdonald was born in England in 1864. In the 1890s, she and her sister Frances moved to Glasgow, where they enrolled at the Glasgow School of Art under the mentorship of Francis Newbery, the school's director, who encouraged decorative arts.

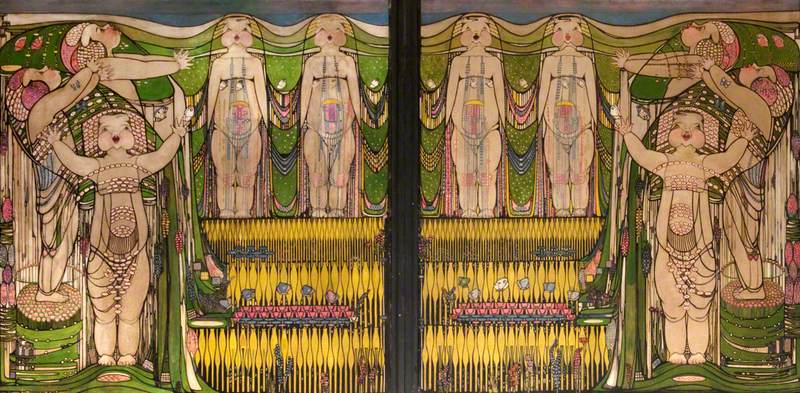

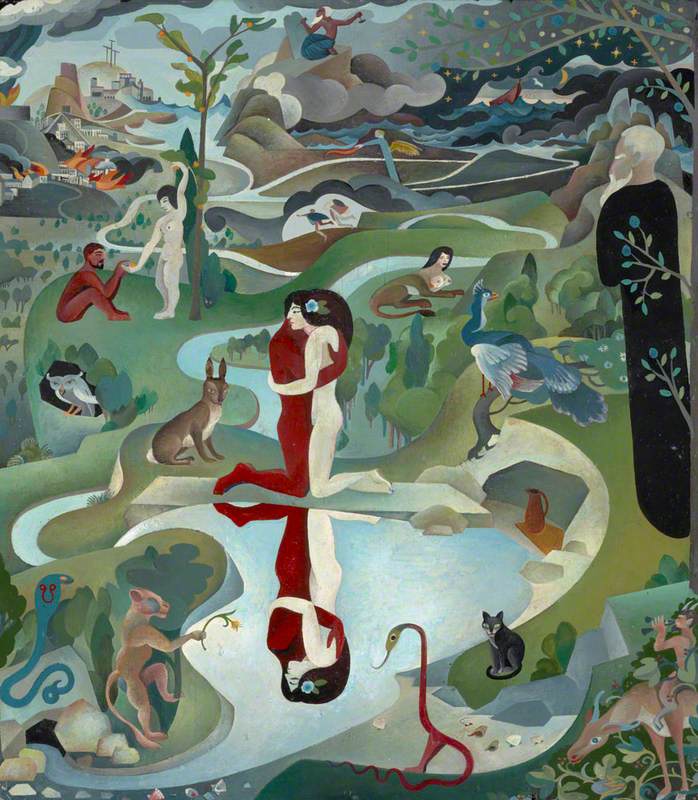

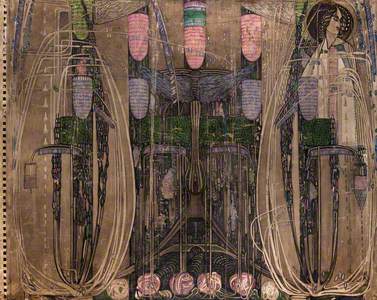

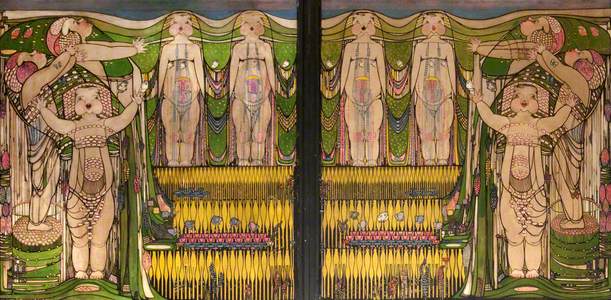

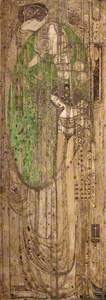

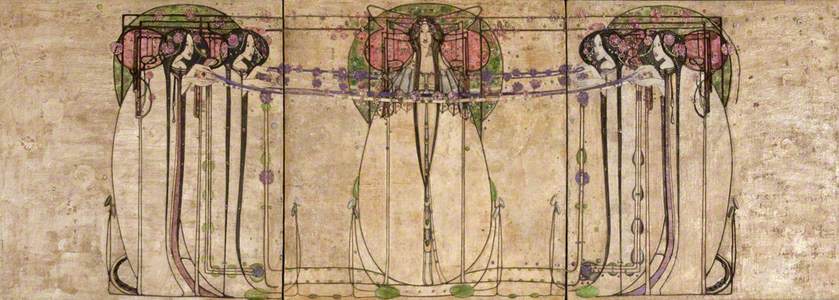

Macdonald participated in around 40 exhibitions across Europe and the United States between 1895 and 1924, and her works were featured in international magazines such as The Studio and Dekorative Kunst. Her distinctly decorative and graphic style combines intricate interweavings of cursive and linear forms, arranged repetitively within vegetal structures. One can discern elongated, emaciated human figures and stylised plants within her work, as seen in 'O ye, all ye that walk in Willowwood'.

'O ye, all ye that walk in Willowwood'

1903

Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh (1864–1933)

Her inspiration is clearly Symbolist, drawing references from the writings of Maurice Maeterlinck, William Morris, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti. She also explores themes from the Bible and other universal texts, while engaging with broader concepts such as death, time, and love. Throughout the 1890s, she went through various phases of experimentation, both in terms of mediums and art itself.

The originality and creativity of her work occasionally provoked hostility from critics. These experiments helped her define her unique style and preferred medium: gesso, a plaster-like material requiring great technical skill, which allowed her to create complex and detailed compositions that brought her imaginative visions to life. She also worked with other materials and techniques, including metal, textiles, and watercolours, showcasing her versatility as an artist.

Collaboration was essential to Margaret Macdonald. Throughout her life, she worked closely with three artists: her sister Frances, her brother-in-law MacNair, and her husband Charles Rennie Mackintosh, with whom she formed a powerful creative partnership. Together, they created iconic works of the Glasgow Style, such as the gesso panels for Miss Cranston's tea rooms on Ingram Street, The May Queen in 1900, and in the Hill House, Sleeping Princess in 1908.

Margaret Macdonald's impact on design is substantial. Although her contributions were often overshadowed by her husband's fame, her work has since gained the recognition it deserves, solidifying her legacy as a key figure in the Glasgow art scene.

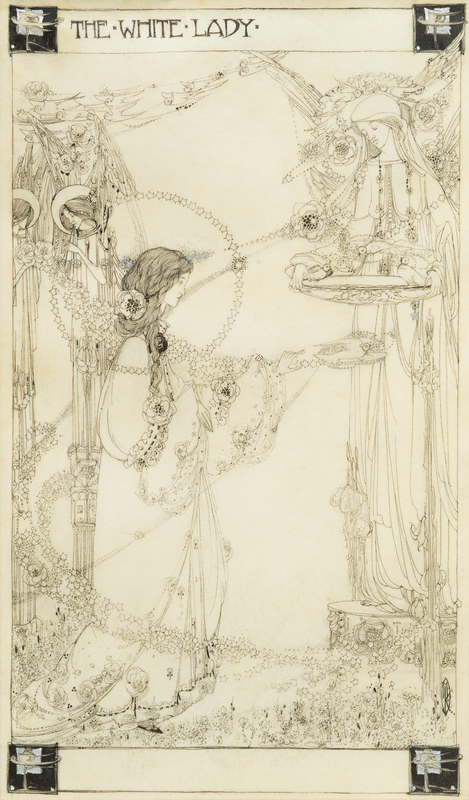

Jessie Marion King (1875–1949)

Born in Scotland in 1875, Jessie M. King studied at the Glasgow School of Art from 1892 to 1899, alongside many of her contemporaries.

Jessie M. King was one of the most commercially successful designers of her time, known for her prolific career as an illustrator on around 80 books, such as A House of Pomegranates by Oscar Wilde.

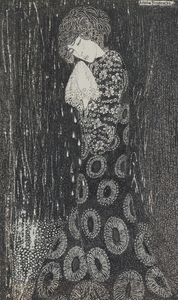

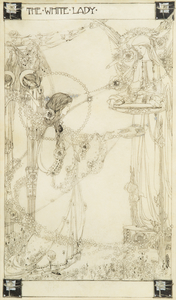

She exhibited her work widely and won numerous awards, including a gold medal at the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative Art in Turin. King's illustrations were celebrated for their detailed and whimsical style, often featuring exquisite linework and fairy-tale imagery, as seen in The White Lady.

She believed she was chosen by fairies to communicate their world to others and claimed to see her images clearly with her 'inner eye'. For King, imagination was more important than faithfully reproducing nature, and she was committed to following her unique vision rather than imitating others.

In addition to illustration, King ventured into jewellery design for Liberty and Co., producing designs for their Cymric line. She also worked with ceramics, showcasing her diverse artistic talents. King and her husband, E. A. Taylor, established an artist colony in Kirkcudbright at their home, Greengate.

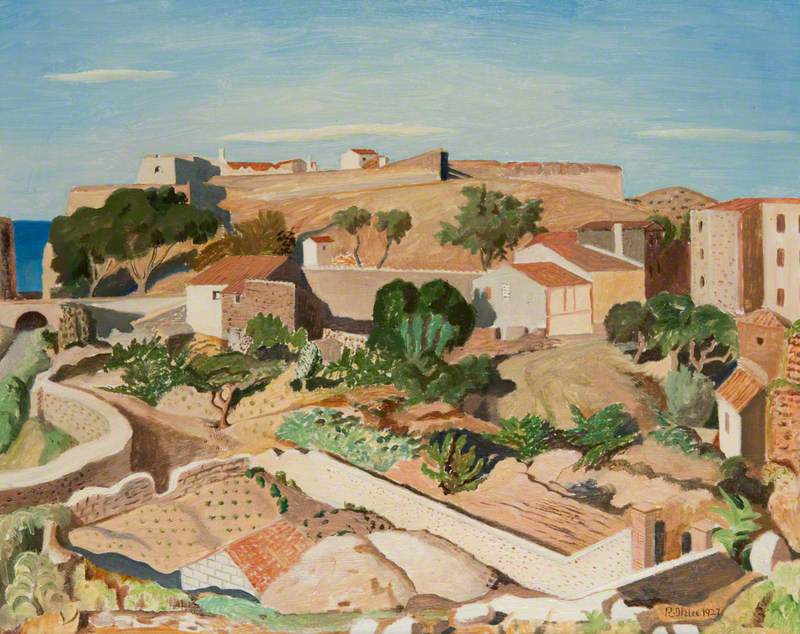

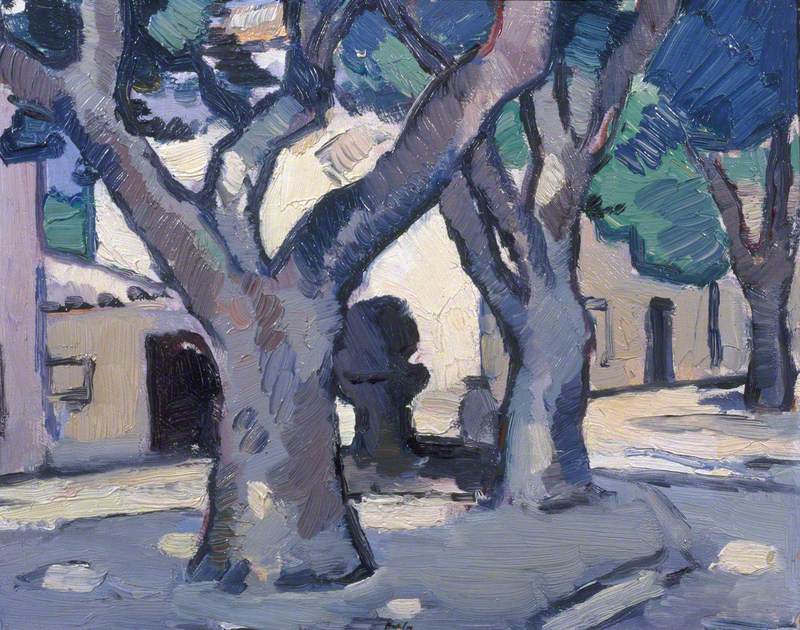

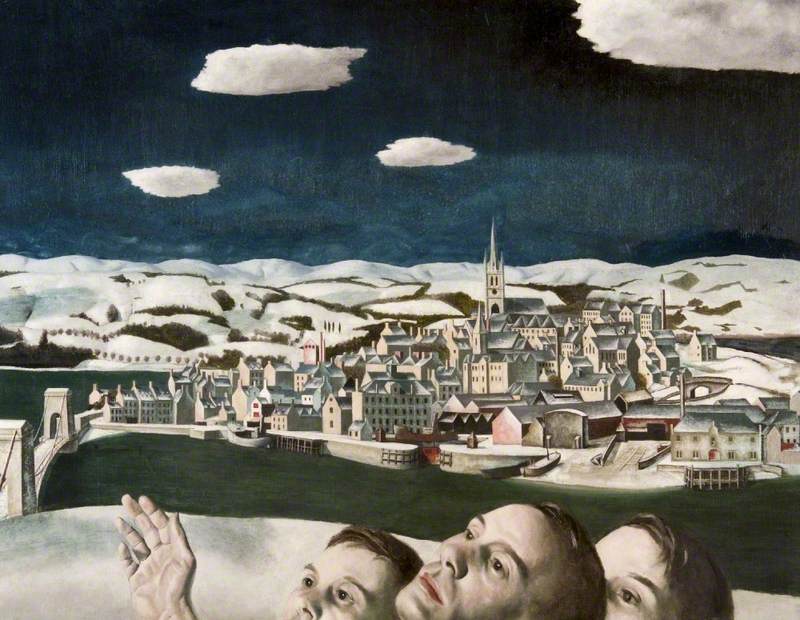

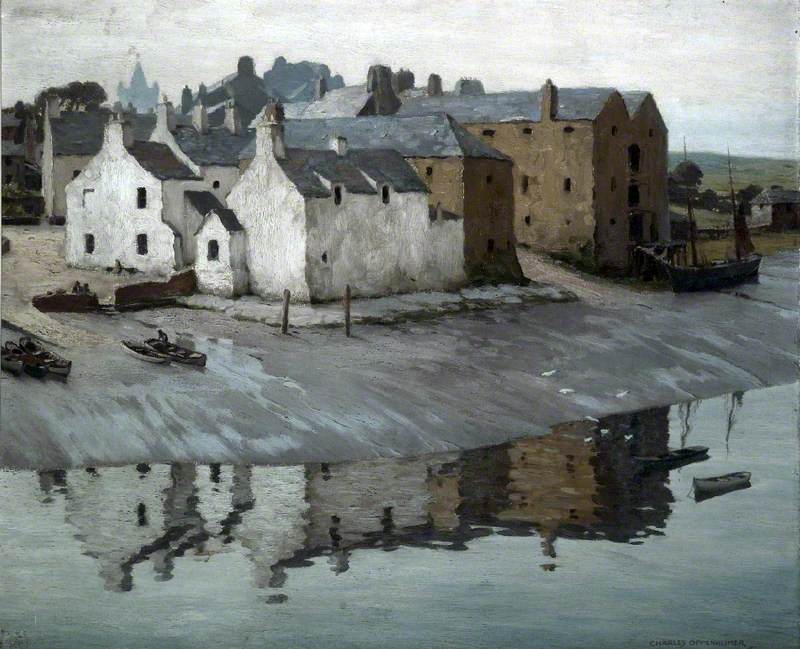

Greengate Close, Kirkcudbright, Dumfries and Galloway

1940–1980

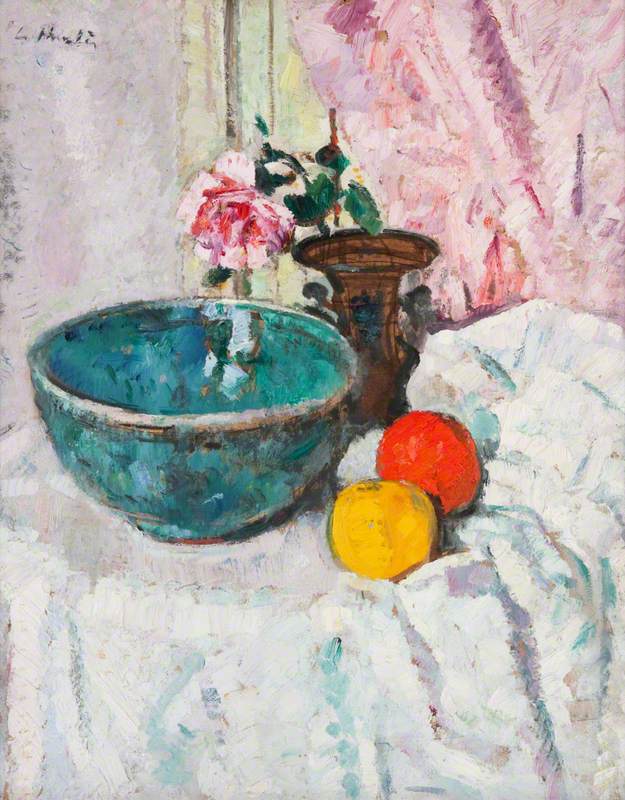

Dorothy Johnstone (1892–1980)

Many artists, including Edward Atkinson Hornel of the Glasgow Boys and Bessie MacNicol, stayed there. They also encouraged women to pursue artistic careers.

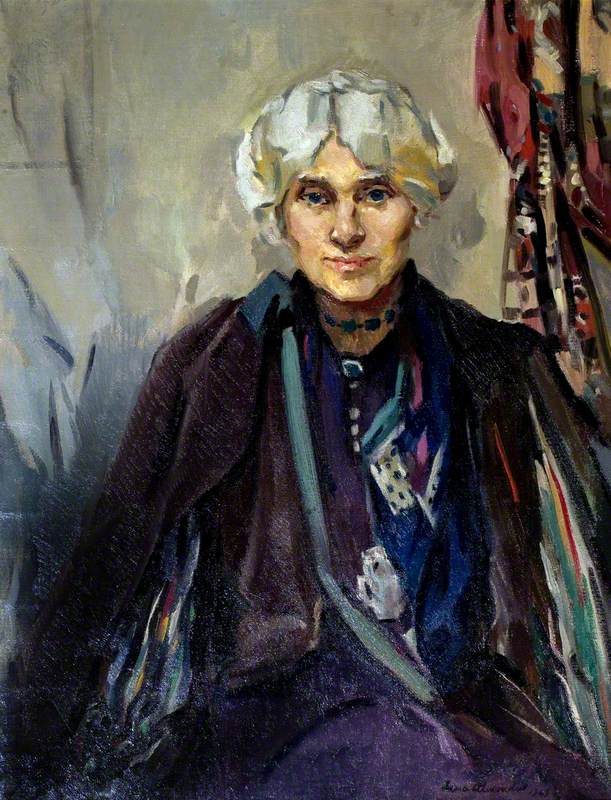

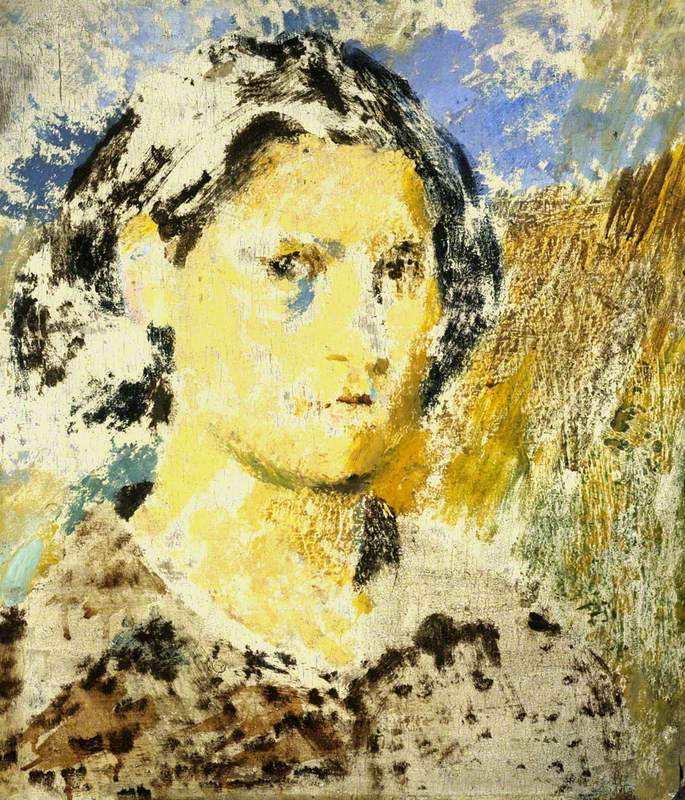

Bessie MacNicol (1869–1904)

Bessie MacNicol was born in 1869 in Glasgow, Scotland. Her artistic talent was evident from a young age, leading her to formal training at the Glasgow School of Art under influential teachers like Fra Newbery and James Guthrie.

MacNicol was the most significant female painter in Glasgow at the turn of the century. Scottish art historian and director of the National Galleries of Scotland, James Caw, remarked after her death that she was, 'probably the most accomplished woman artist that Scotland has produced so far.'

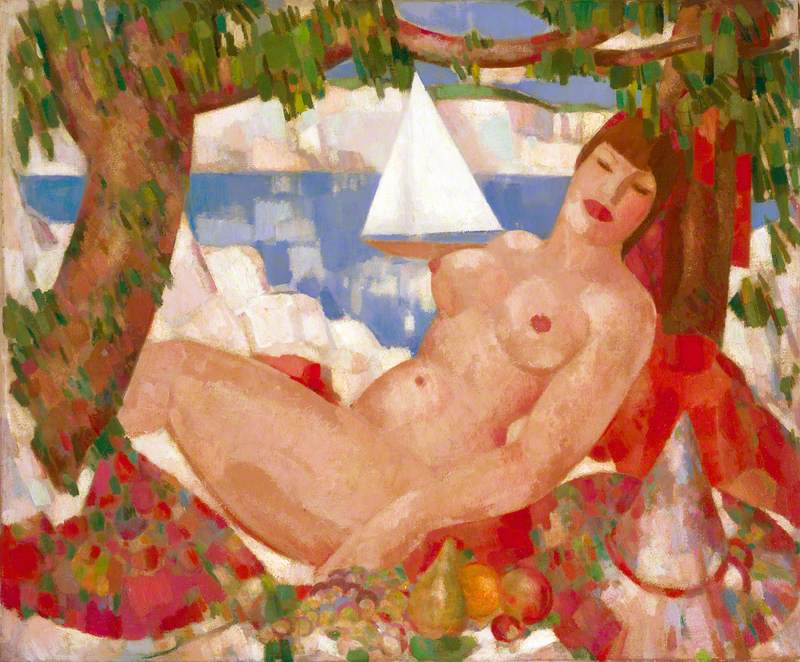

MacNicol's style was heavily influenced by the Impressionists, with a use of light and colour characteristic of that movement, but with a more pronounced realism. She excelled in portraiture and landscapes, often depicting young girls outdoors, under trees, in soft, diffused light – as seen in numerous portraits such as Under the Apple Tree or Autumn.

She was part of the Kirkcudbright school. Her work is distinguished by delicate brushwork and attention to detail, reflecting the Glasgow School's emphasis on decorative elements combined with a realistic approach.

Although Bessie MacNicol's career was tragically short – she died in 1904 at the age of 35 – her work left a lasting impression on Scottish art. During her lifetime, she exhibited widely across Europe and the USA, where her work was well received. She is recognised as an important figure in the development of Scottish art, particularly within the context of the Glasgow School movement.

The Glasgow Girls, with Margaret Macdonald as a leading figure, played a crucial role in shaping the Glasgow Style and promoting the role of women in art. Their contributions, long overshadowed, are now recognised as vital to Glasgow's cultural heritage and beyond. Through their creativity, determination, and spirit of collaboration, these women secured their place in art history.

Louise Jacquier, art historian

This content was funded by the PF Charitable Trust

Further reading

Anthea Callen, Angel in the studio: Women in the Arts and Crafts movement 1870–1914, Astragal Books, 1979

Jude Burkhauser, Glasgow girls: Women in art and design, 1880–1920, Canongate Publishing, 1988

Liz Arthur, Glasgow Girls: Artists and Designers 1890–1930, Kirkcudbright 2000 Ltd, 2010

Alison Brown, 'Re-evaluating the Glasgow Girls. A timeline of early emancipation at the Glasgow School of Art', II coupDefouet International Congress, 2015