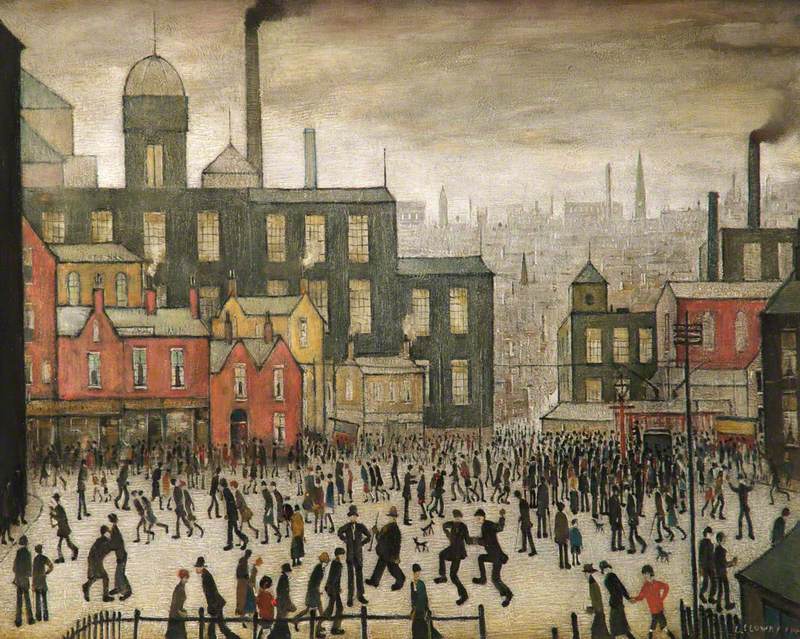

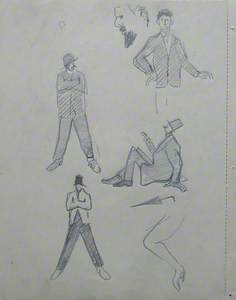

On 22nd October 1938, Manchester City beat Sheffield United 3-2. Among the 30,000 supporters on Maine Road's terraces that day stood a cloth-capped L. S. Lowry. The fixture, which Lowry later depicted in his painting Manchester City vs Sheffield United (1938), was one of a number of times he attended Maine Road.

Manchester City vs Sheffield United

1938, oil on canvas by Laurence Stephen Lowry (1887–1976)

A lifelong City fan, Lowry would trundle across the cobbled streets of Manchester from his home in Pendlebury, capturing individual moments that would later appear on canvas, and placing bets with his friends on different outcomes of the match.

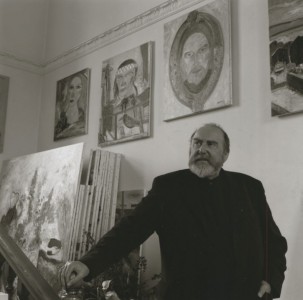

L. S. Lowry

late 1920s, half-plate glass copy negative by Elliott & Fry (active 1863–1962)

One time, when the bet hadn't gone his way, Lowry offered to pay out in paintings, rather than shillings. This proposition was met with horror by his friend, who remarked, 'I've got a four-year-old son at home who can draw better than that. I'll wait until you can pay me the shilling.' This is the reception to his art that haunted Lowry for much of his life.

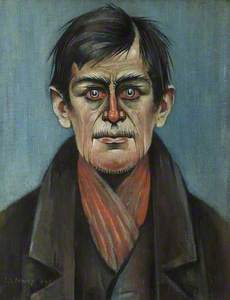

An only child, born into a lower-middle-class family, Lowry grew up in the shadow of his mother's expectations. Never the girl she had desired and indebted to her perpetual ill-health, Lowry would paint to serve as the antidote for what he described as the 'battle of life'. He worked as a rent collector for over 40 years, a profession that allowed him to support himself and his mother while continuing to paint. A master at manipulating his self-image, he would go on to become a colossal artist, who, according to one critic could turn 'sordidness into poetry'.

Portrait of the Artist's Mother

1912

Laurence Stephen Lowry (1887–1976)

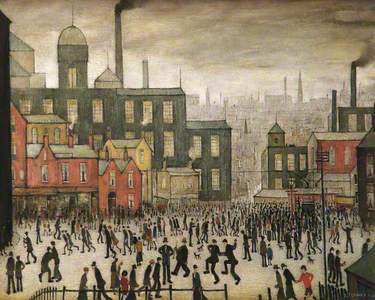

Although many facets of Lowry's personality have been widely explored, his interest in football, and sport more broadly, has rarely been considered in depth. Lowry was the first British artist to seriously grapple with the topic of sport, painting tens of pictures that captured scenes at cricket, rugby and football.

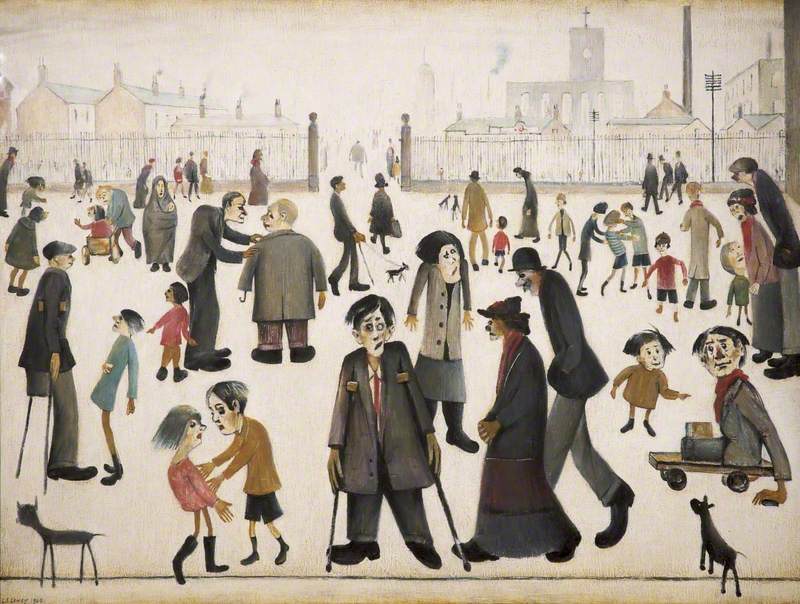

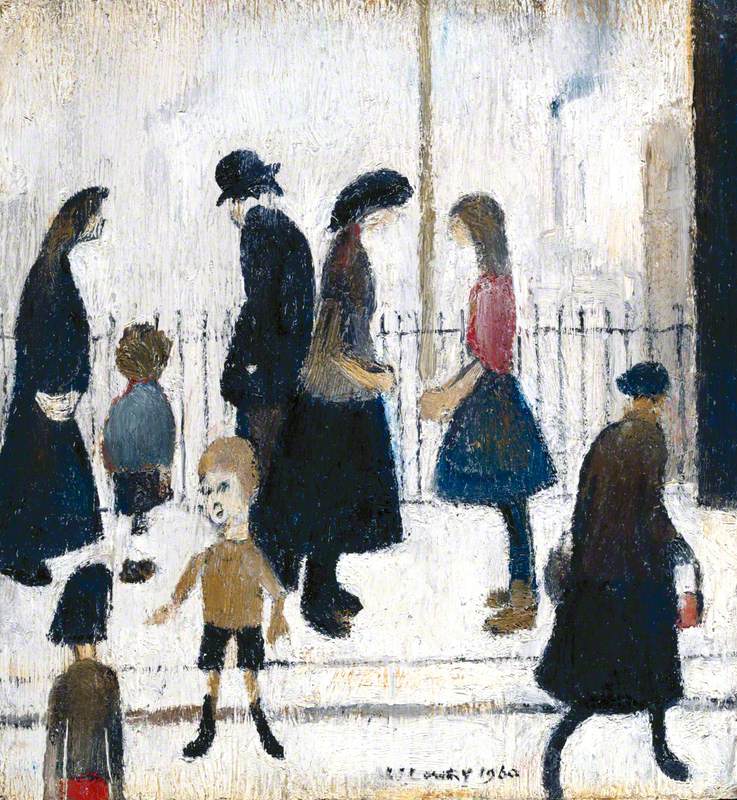

At the centre of these paintings Lowry often depicted rushing spectators, cast in drab hues with oversized feet. His idiosyncratic 'matchstick' figures are temporarily excused from the satanic mills, dizzied with the catharsis of football – an ecstasy Arthur Hopcraft later described as the 'escape from the darkness of despondency into the light of combat.'

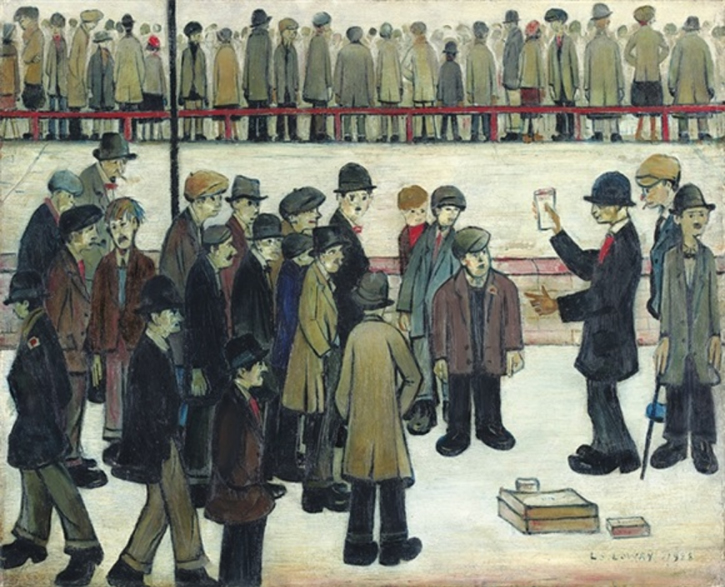

Figure Studies: Head and Umbrella & Two Scenes at a Football Match

(recto & verso) c.1919–1920

Laurence Stephen Lowry (1887–1976)

Yet as football rose to prominence in the early twentieth century, embedding itself in the national psyche and becoming synonymous with the working class, London's art circles distanced themselves from the sport, viewing it as a stain on Britain's interwar character.

Of the few other painters who did deem football a worthy topic during this time was Charles Ernest Cundall and Christopher Nevinson, who painted Any Wintry Afternoon in England (1930).

The painting sets a disorderly group of players before a chalky industrial setting, the billows of smoke casting everything below into darkness. This depiction, which followed Nevinson's description of Manchester as a 'black monstrosity', was his appeal to the straying cultural life of Britain, the uncouth sport that stood in the way of Britain and its future.

Any Wintry Afternoon in England

1930

Christopher Richard Wynne Nevinson (1889–1946)

Such snobbery horrified Lowry. Unlike the writer George Orwell, who witnessed the inhumane conditions of the poor during his time in Wigan in 1936, and sought to dignify their northern spirit, Lowry – as he so often liked to retort – painted things plainly and as he saw them. Lowry's artistic vision was not a politicised, social commentary, but a truthful depiction of the austere conditions that gripped his subjects.

In his paintings, each isolated figure faces their own 'battle of life', much like Lowry, clambering for something beyond the void. Lowry painted football because it consumed them just as much as work, or poverty, or the dirty world of politics.

'I've no real happy memories of my childhood... I've a one track mind, sir. Poverty and gloom,' recalled Lowry in an interview in Shelley Rhode's L. S. Lowry: A Life.

His father, Robert, was an unsuccessful estate agent who rarely displayed any emotion – 'it was as if he had a life to get through and he got through it', Lowry later said. At the weekends Robert would coach the local football team at St Clement's Sunday School, and despite his attempts, never managed to recruit his son.

Instead, Lowry insisted he was 'no good at sport' and consigned himself to the sidelines, watching the world move and transition around him. It was in this role, the spectator, that Lowry remained throughout his life.

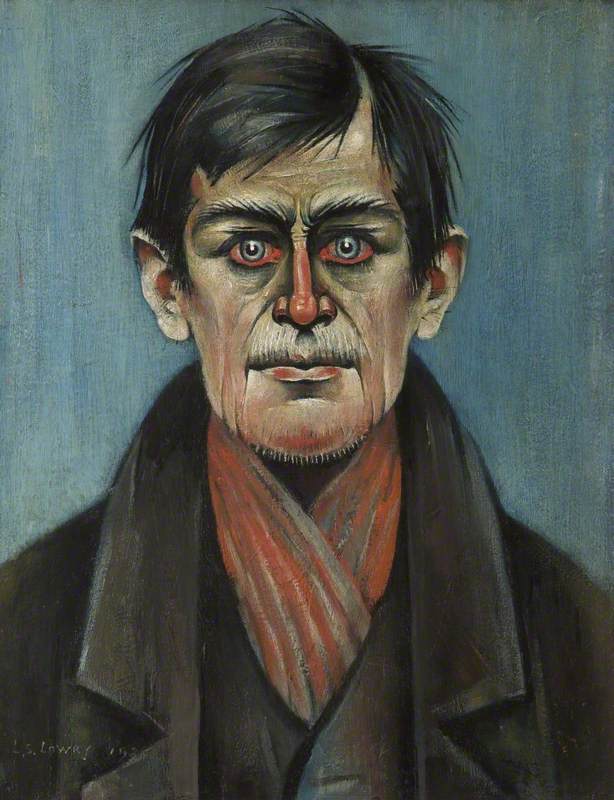

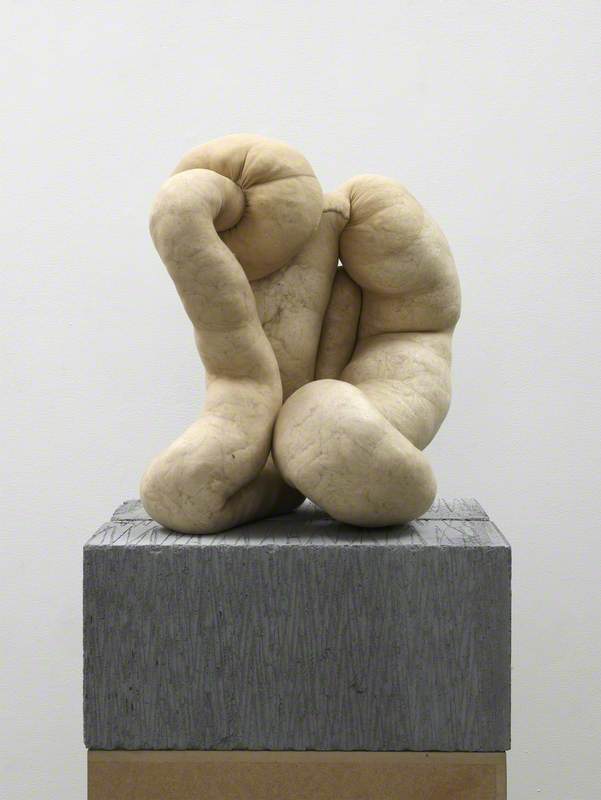

Lowry's isolation ran throughout much of his work. After his father died in 1932, which left Lowry with huge debts and the sole care of his bedridden mother, he spent the next seven years by her bedside, seldom leaving other than to do his rounds of rent-collecting or to paint upstairs in the attic. Lowry later described this as 'the most difficult period of my life'. He was 'tied to his mother', his anguish captured in the face of his self-portrait, Head of a Man (1938).

Only while trundling through the streets of Manchester did he witness the world – in all its ordinariness. He ceaselessly observed but remained detached from his surroundings. It was perhaps through this detachment – in pursuit of meaning beyond the heavy skies of Cottonopolis – that Lowry found his love of football.

Football, as a sport that was shared by and united the community, allowed ordinary workers to temporarily forget their woes and hardship. Lowry understood this, in a way that he didn't understand the inside of a mill, or the foot of a coalpit. In football, he found not only a purpose but somewhere he belonged.

Yet it was not Lowry's simple soul reckoning with the human condition that brought him to fame and popularity in the post-war era. In the aftermath of war, Britain had a dire need for modernisation and cultural shift that attempted to bury the bleak insufficiencies of the 1930s. It was Lowry who was on hand to capture this change.

Historian Chris Waters wrote that Lowry embodied 'a desire to remember' which was 'paralleled by the pressure to forget.' It was in this mould, the 'English Lowry', the local artist who evoked a deep sense of nostalgia for a fading Britain, that he rose to national reverence.

During this period Lowry painted Going To The Match (1953) and The Football Match (1949), the latter fetching £5.3m at auction in 2011. His paintings, once scoffed at as depicting grubby scenes that 'could be seen from the number 8 bus', now became the physical rememberings of forgotten lives, taking pride of place in living rooms across Greater Manchester.

The Football Match by Laurence Stephen Lowry 1949 (Private Collection). pic.twitter.com/MMAdUPXClz

— Dr Liv Gibbs (@DrLivGibbs) May 27, 2017

It was somewhere in between these two that Lowry found his true appreciation for football. Not solely as an escape from the burdens of the interwar existence, but as a British game woven into the very fabric of working-class life. Among football's plights and pleasures, its meaningful hollowness, its conflict and unity, could be found the spirit of ordinary Britons, standing powerlessly before the forces of industrialisation, poverty and war.

Football was the solace, a temporary transcendence from the material struggles, a permanence that lay at the centre of British life while the rest of the nation changed. This, for Lowry, was not just worthy of his attention, but a dedication that only those who stood beside him on the terraces could understand.

James Beardsworth, freelance writer

Further reading

Chris Waters, 'In Representations of Everyday Life: L. S. Lowry and the Landscape of Memory in Postwar Britain', No. 65, Special Issue: New Perspectives in British Studies, 1999, pp.121–150