The Fleming Collection was started in 1968 as a corporate collection of Flemings, a former merchant bank based in the City, as a way to brighten up newly acquired London offices. In a nod to the bank's founder Robert Fleming, born in Dundee in 1845, only paintings of the Scottish landscape or works by Scottish artists were collected.

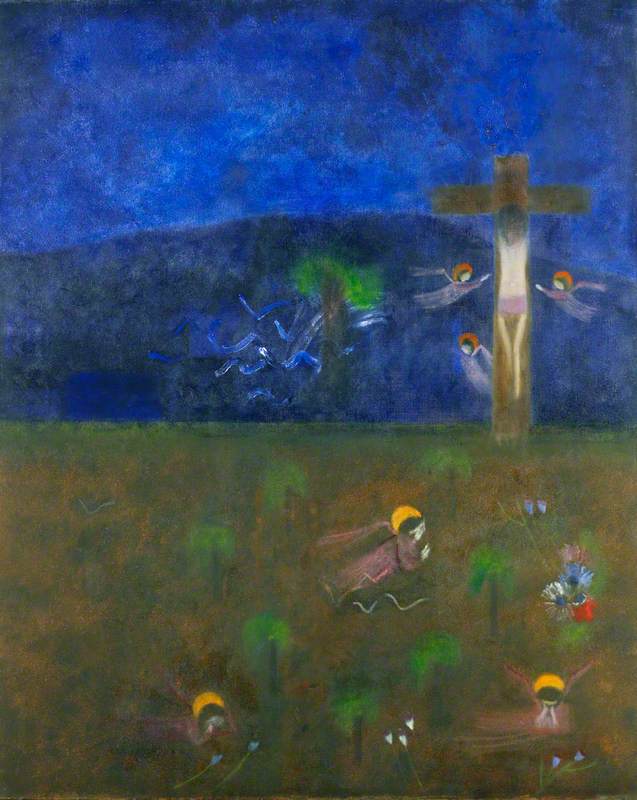

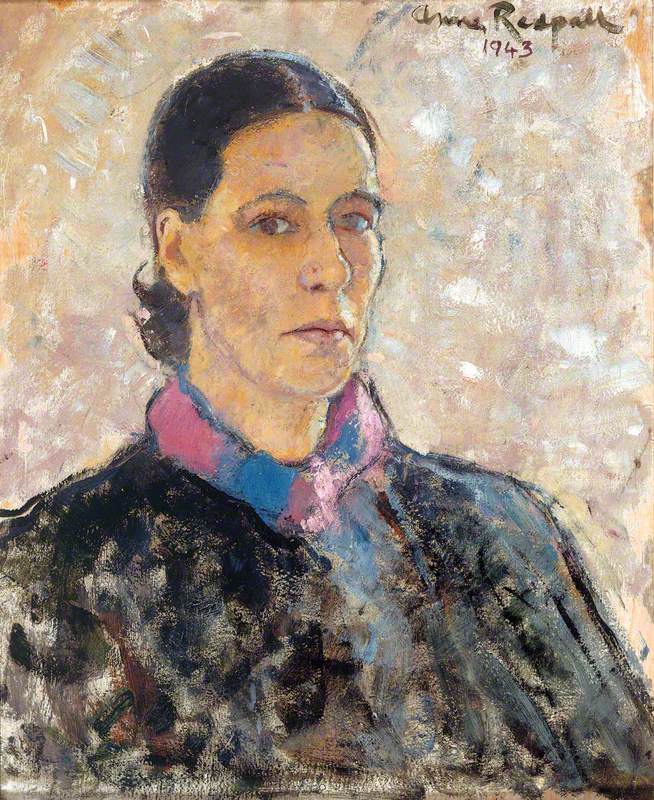

The collection comprises almost 800 works dating from 1770 to the present day, including works by the Glasgow Boys, Anne Redpath and the Scottish Colourists as well as iconic paintings of the Highland Clearances and works by contemporary Scottish artists. New works are regularly acquired with the current focus on those by young Scottish artists and taking opportunities to fill historical gaps in the collection.

In June 2011 The Fleming Collection opened a second exhibition space, allowing the gallery to show a selection from the permanent collection whilst still championing Scottish art through a changing exhibitions programme.

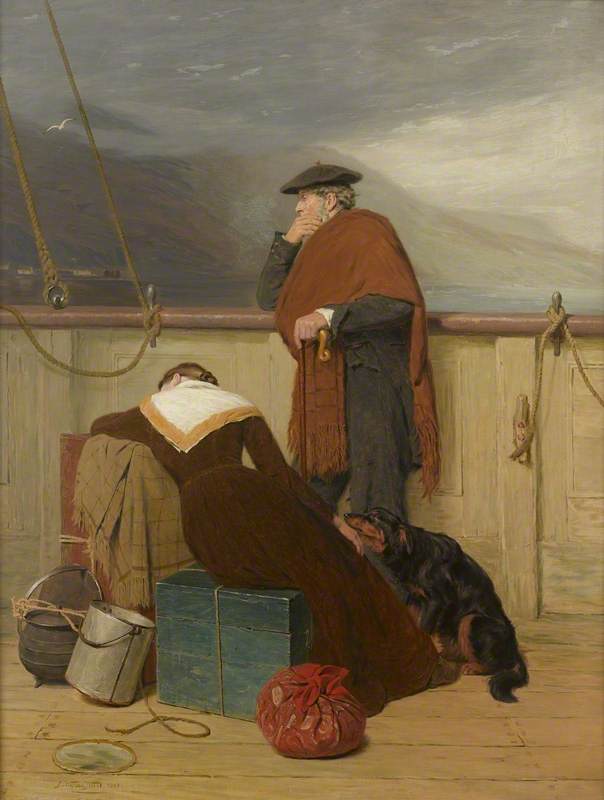

This curated selection of works takes a new, comprehensive look at our extensive collection of Scottish art and the themes that run through it. Scottish identity and seascapes give an insight into the concerns of artists addressing their heritage and culture. One of the first and most significant works acquired certainly encapsulates the ethos of the collection.

John Watson Nicol's Lochaber No More is an emotive work depicting the Highland Clearances, giving an insight into the plight of those who were forced from their homes in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

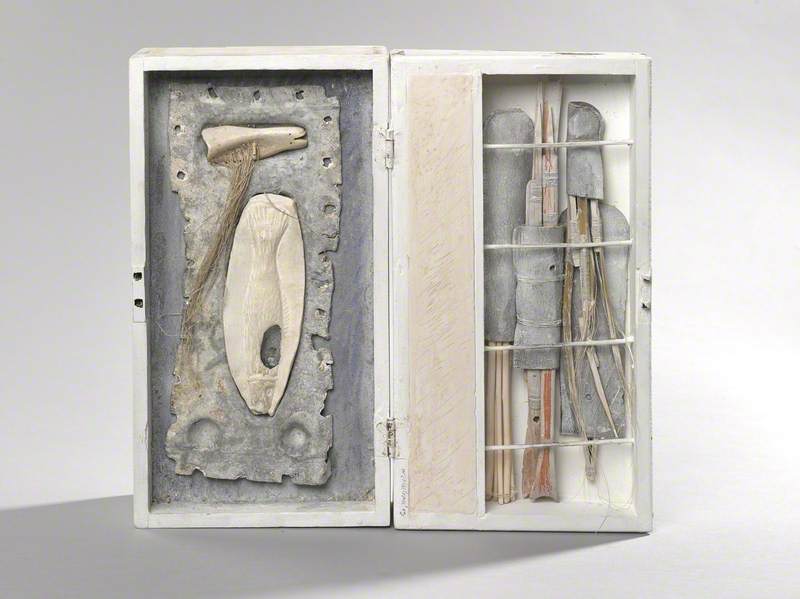

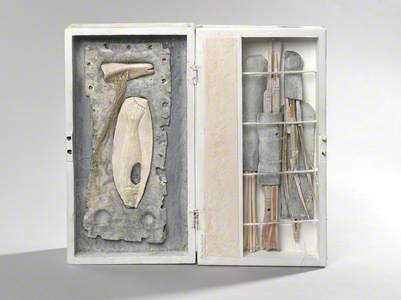

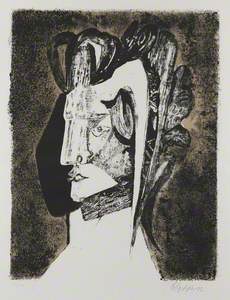

This displacement continued to be felt throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. For Will Maclean, Scottish identity and the desire to reclaim lost Gaelic traditions and a faded highland maritime culture are major themes in his work.

Maclean's sculptures and constructions act as sensitive memorials of the viewer with an overwhelming sense of loss, particularly of the Gaelic language. Maclean was part of the first generation to be denied a direct connection to the traditions and language native to his family heritage. His artwork deals with both his own personal history and the greater concerns of the Gaelic poets.

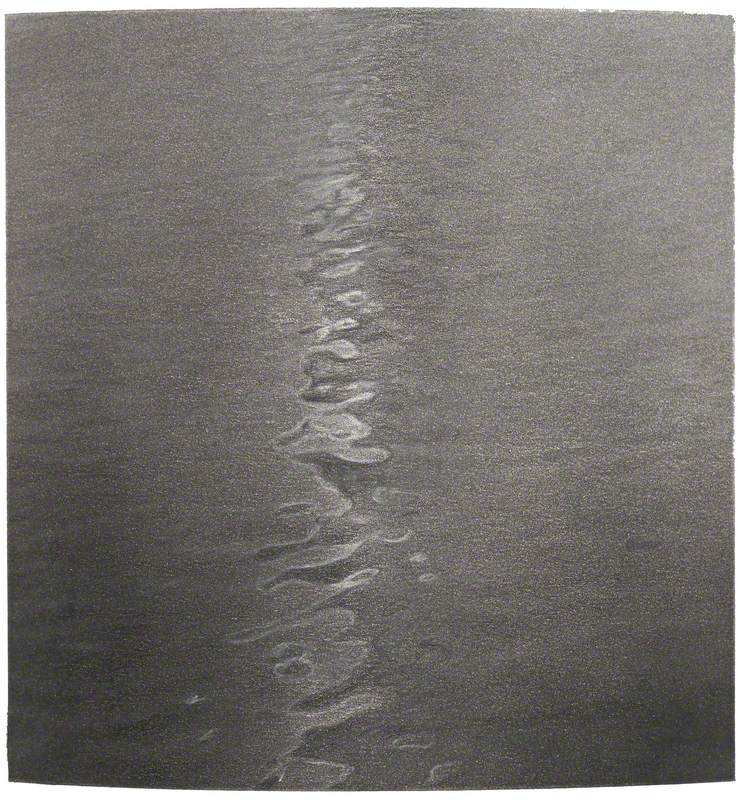

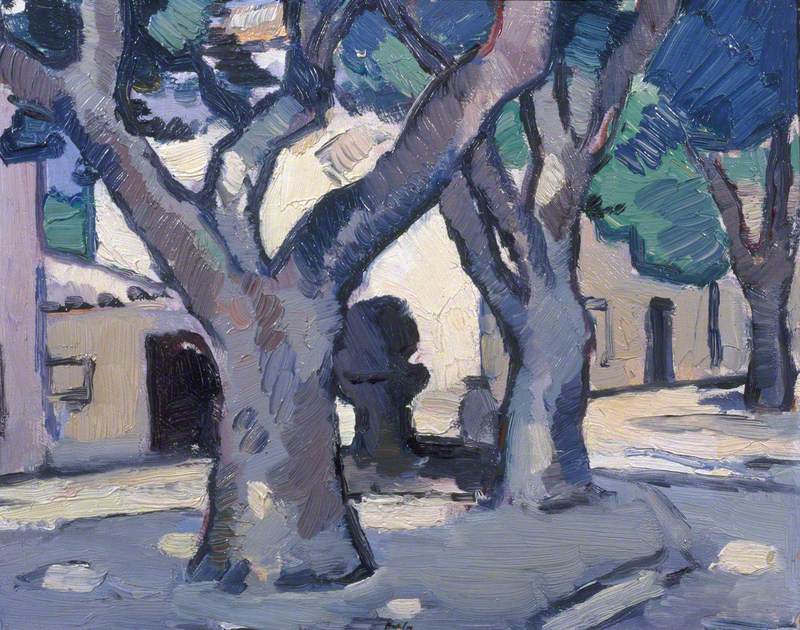

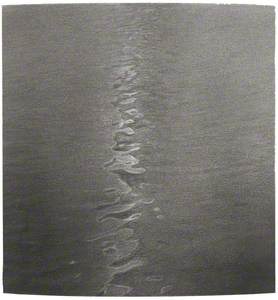

The intensity of light which many Scottish artists, including the Colourists, were captivated by in the Mediterranean could also be found in Scotland. Joan Eardley was one such artist, who, after discovering the small fishing village of Catterline in 1950, returned continually to capture powerful, expressive images of the coastline of North-East Scotland in all weather conditions.

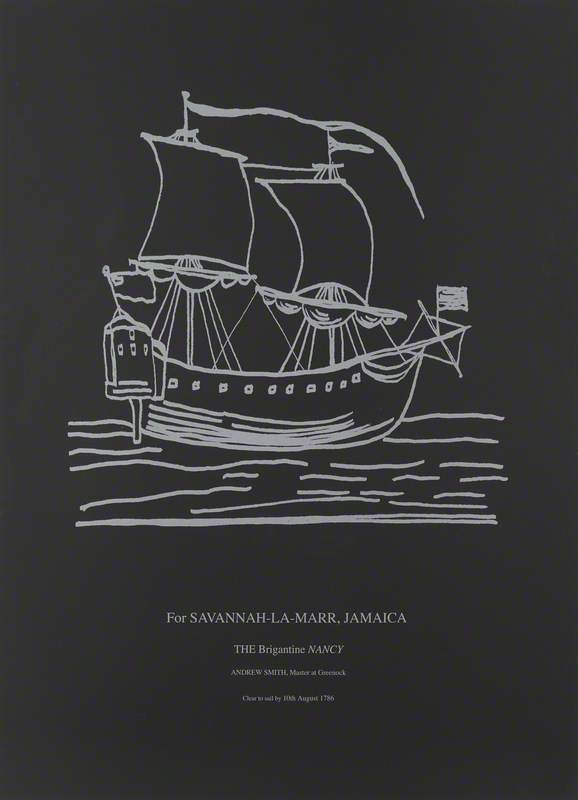

Graham Fagen's screen print Nancy is part of a series which depicts the boats that the Scottish poet Robert Burns had booked passage on in his abortive attempt to emigrate to Jamaica in 1786.

However, the success of his first book of poems improved his financial circumstances and he remained in Scotland. The print reproduces the advertised details of the ship: its name, the ship masters, and the date and port of its embarkation, acting as a succinct reminder both of how history can be radically diverted and of the more sinister side of Scotland's maritime history. In 2006 Fagen made the journey to Jamaica that Burns never did, travelling to Savannah La Mar, where Scotland's national poet would have docked had he taken his first passage on board the Nancy.

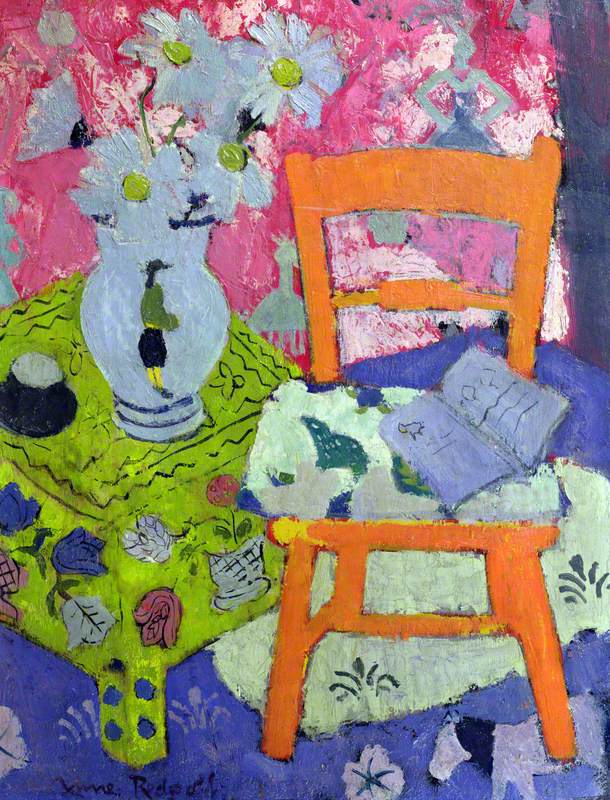

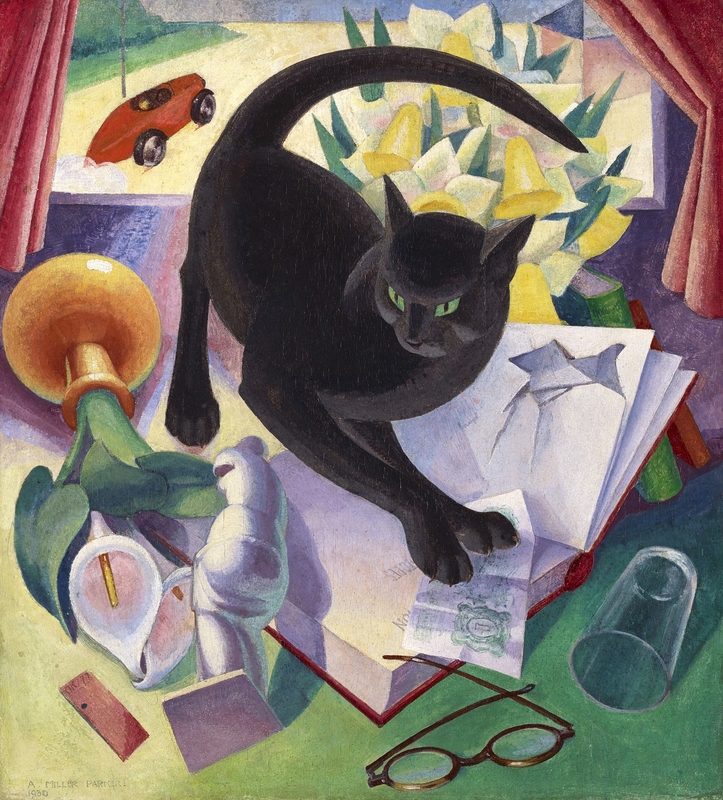

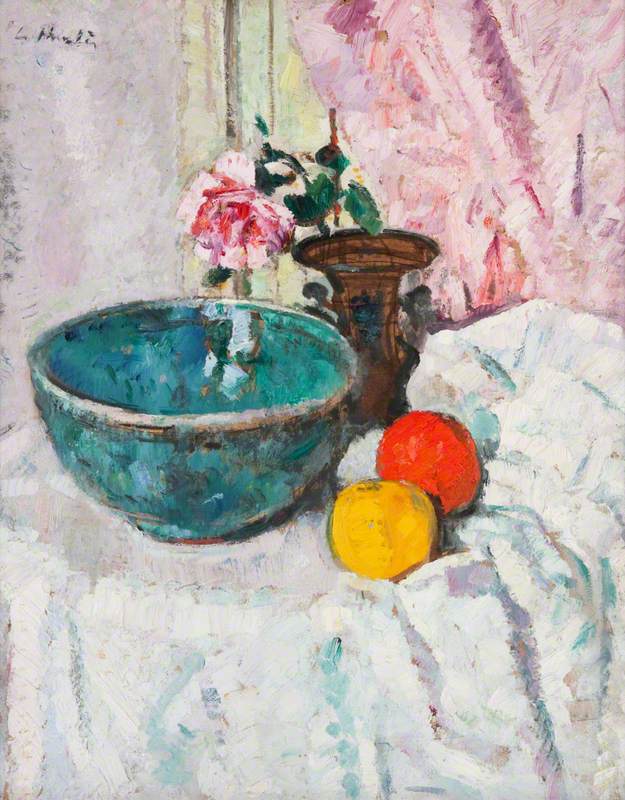

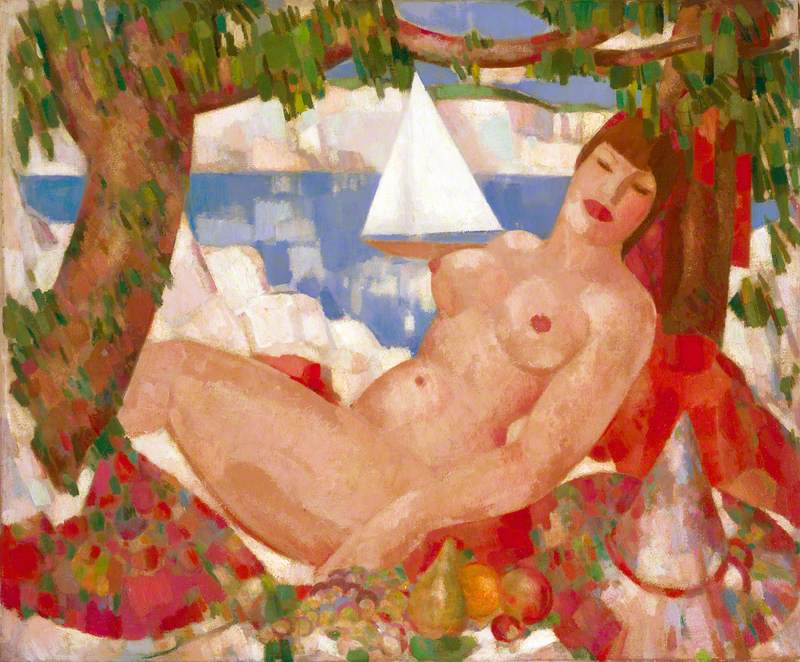

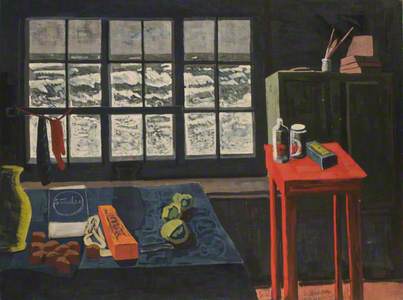

Still lifes and domestic scenes illustrate the influence of the Scottish Colourists, who used the subject matter of the still life to experiment with strong and vibrant colours to form their influential style.

The still lifes painted by Samuel John Peploe, John Duncan Fergusson, Francis Campbell Boileau Cadell and George Leslie Hunter remain their most renowned and accomplished works. Much like still lifes, domestic scenes were popular with wealthy patrons, and allowed stylistic yet decorative experimentation.

While these conventions are typified in Cadell's Roses, Elizabeth Blackadder's work turns such traditions on their head. Though the subject matter and medium – predominately watercolour – appear to conform to the stereotypical accepted domestic concerns of female artists, Blackadder's arrangement of pictorial space and her subversion of the traditional depiction of the accepted genre for female painters constitutes a dislocation from the norm.

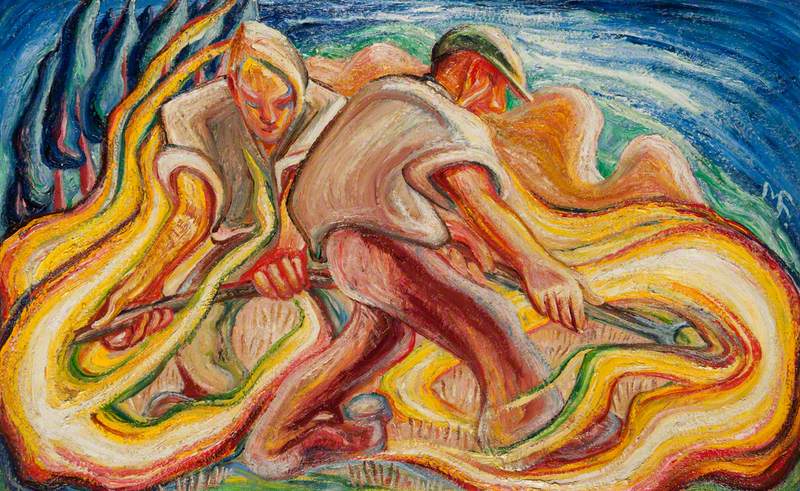

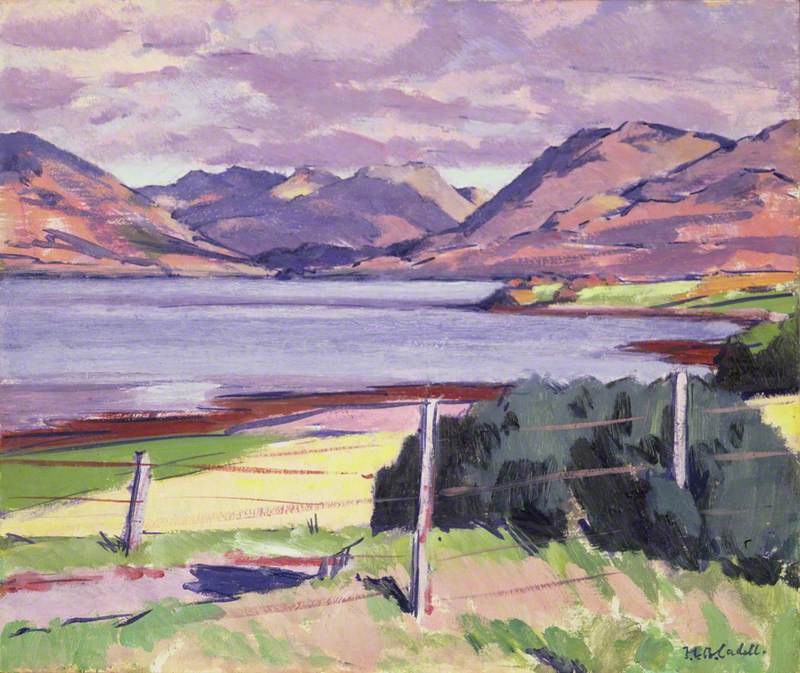

Landscape works demonstrate that the distinctive Scottish landscape has been one of the principal subjects employed by artists for centuries. The challenge of portraying such dramatic wilderness and coastline has been taken on by many of Scotland's most renowned artists, all contributing to the emergence of a national identity which often portrays the country in a romantic or celebratory light. This somewhat stereotypical view of Scotland was becoming outmoded by the late nineteenth century, in part due to the introduction of photography.

Many artists sought to capture a more realistic representation of both the natural world and the lives of those living and working in it. Artists such as William McTaggart began to paint outdoors, embracing a more discreet approach which continued to make the genre relevant for artists such as the Glasgow Boys and the Scottish Colourists, who were strongly influenced by French landscape painting.

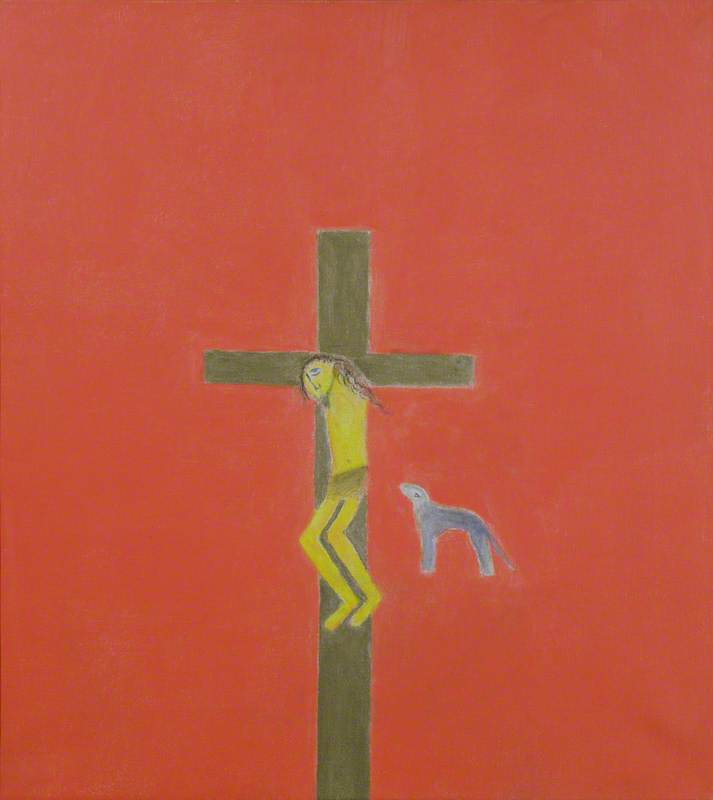

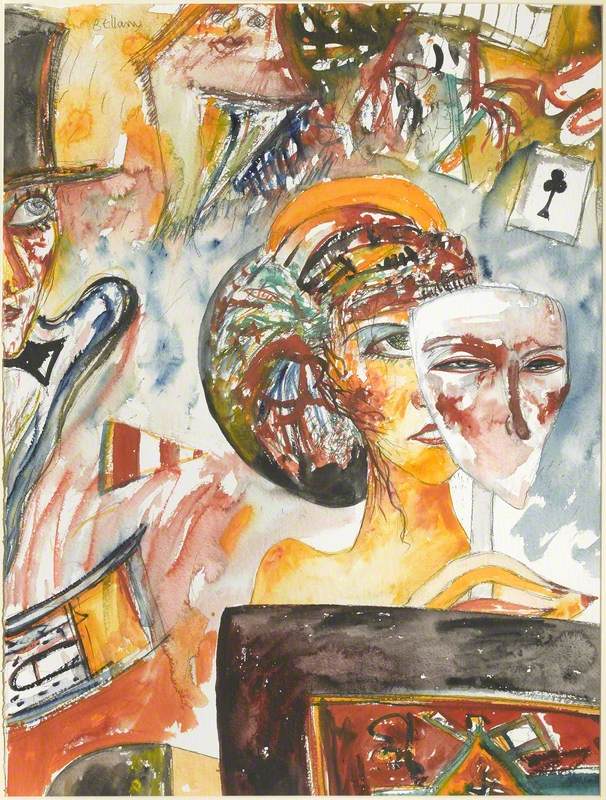

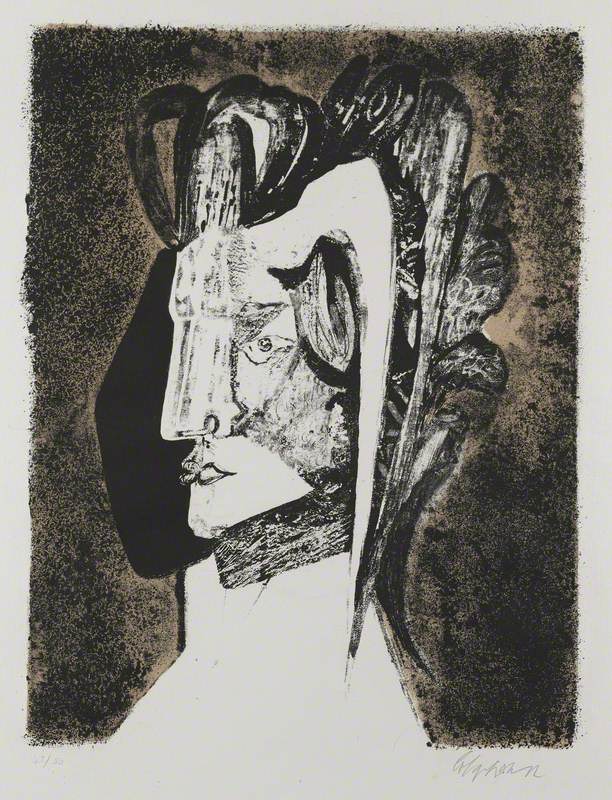

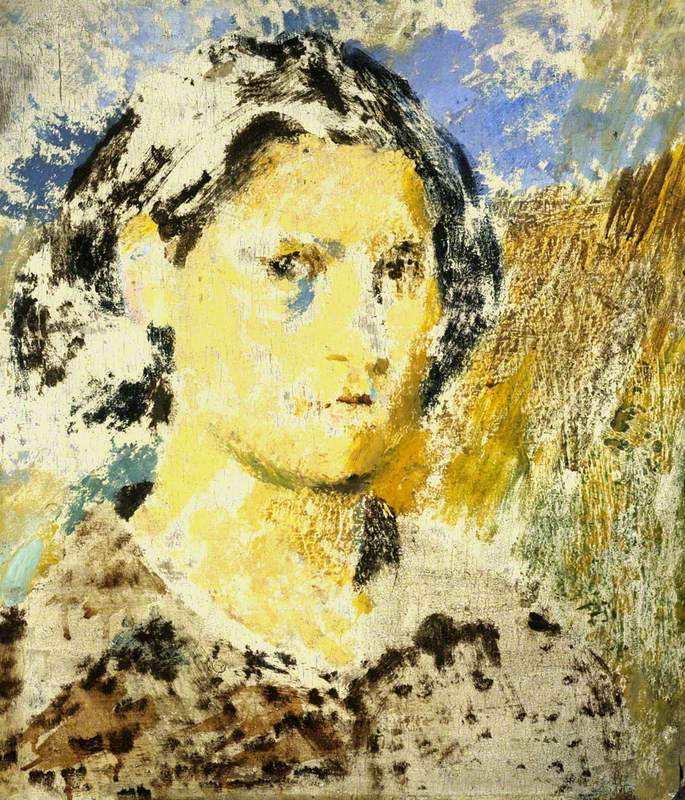

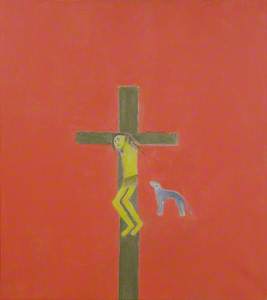

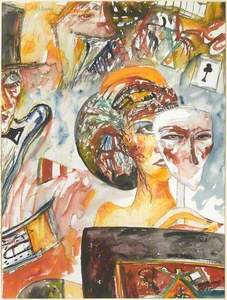

Similarly to landscape painting, portraiture provided a subject which could transcend the conventions of traditional Scottish painting to include the influence of modernist continental painting which so fascinated Scottish artists.

This move into more abstract and experimental painting paved the way for future Scottish artists and the ongoing innovation and reassessment that continues to make Scottish art so stimulating.

Sophie Midgley, Former Gallery Manager, The Fleming Collection