In the memoirs he penned just before his death in 1941, Sir John Lavery, an impossibly well-connected portraitist and socialite, expressed a degree of shame at 'having spent my life trying to please sitters and make friends instead of telling the truth and making enemies'.

The comment strikes a rare minor note in a lengthy self-portrait of a charming pragmatist, whose passage through the Realist milieux of the Glasgow School during the 1880–1990s saw him emerge by the close of the century, perhaps ironically, as a sought-out portraitist of the international aristocracy.

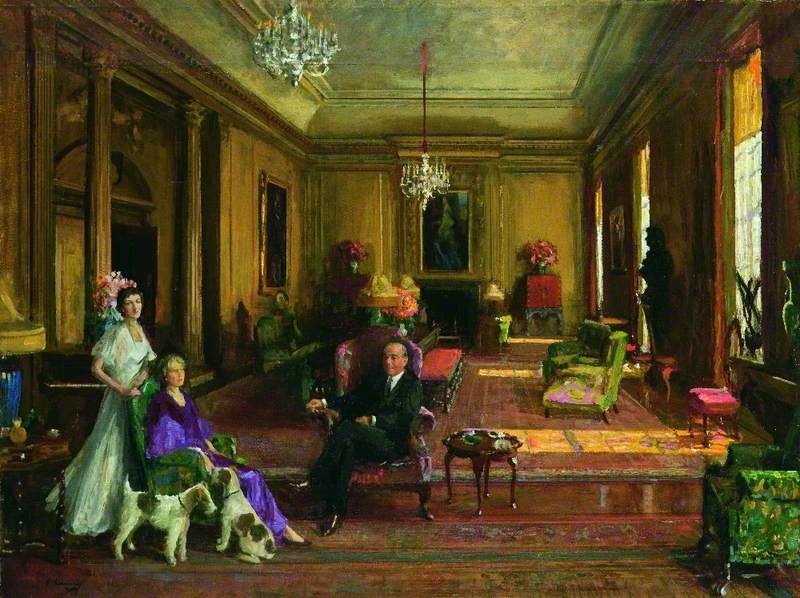

Lavery would enjoy several more reincarnations, notably as an official First World War artist and latterly as a painter to various Hollywood stars, including an eight-year-old Shirley Temple in 1936. Between those phases, his powers of diplomacy, and those of his wife, the Irish-American artist and heiress Hazel Martyn, saw them play a central role in the forging of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, when the couple hosted the Home-Rule party (with whom their final sympathies lay) for negotiations in London during 1921.

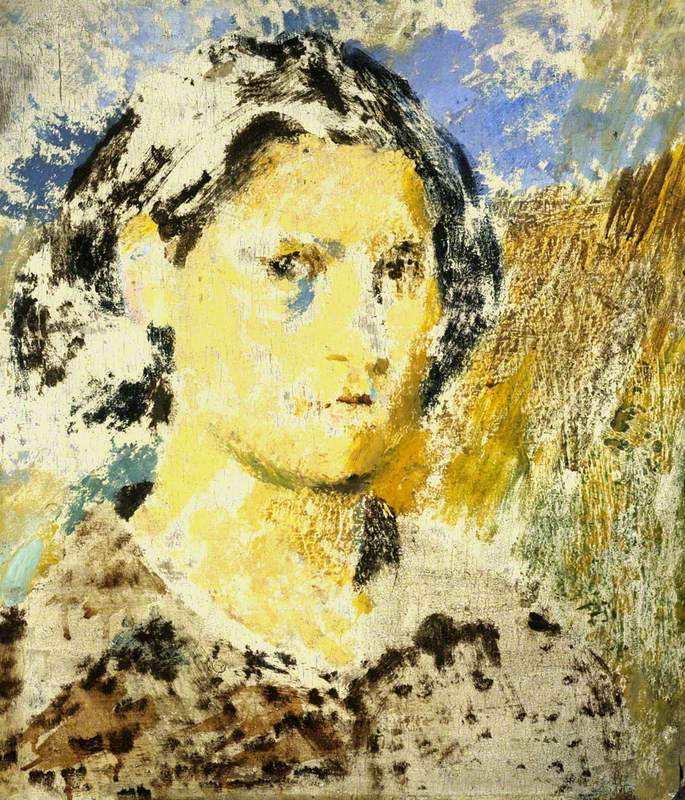

Hazel Martyn (1880–1935), Mrs Lavery (formerly Mrs Trudeau), Later Lady Lavery

c.1906/1909 (?)

John Lavery (1856–1941)

It would be easy to lose sight of Lavery's artistic heritage and scratchy origins amongst the glamour and intrigue of his biography. Born in Belfast in 1856 to a publican father, he was orphaned at a young age and raised by an uncle in County Down, then by a distant relative in Ayrshire.

By the age of 17, he was working as a photographer's assistant in Glasgow, already a self-styled 'artist' although at times near destitute. Periods of training at the School of Art in the city and at Heatherley's in London followed, before Lavery made the habitual pilgrimage of the Glasgow generation to Paris.

Ironically, given the Glasgow School's progressive affiliations, he was taught at the Académie Julian by the neo-classicist Bougeureau, reviled by the Impressionists for his fussiness, but it was from the Realist and Naturalist schools that Lavery learned the most: primarily from their prodigal figurehead Jules Bastien-Lepage.

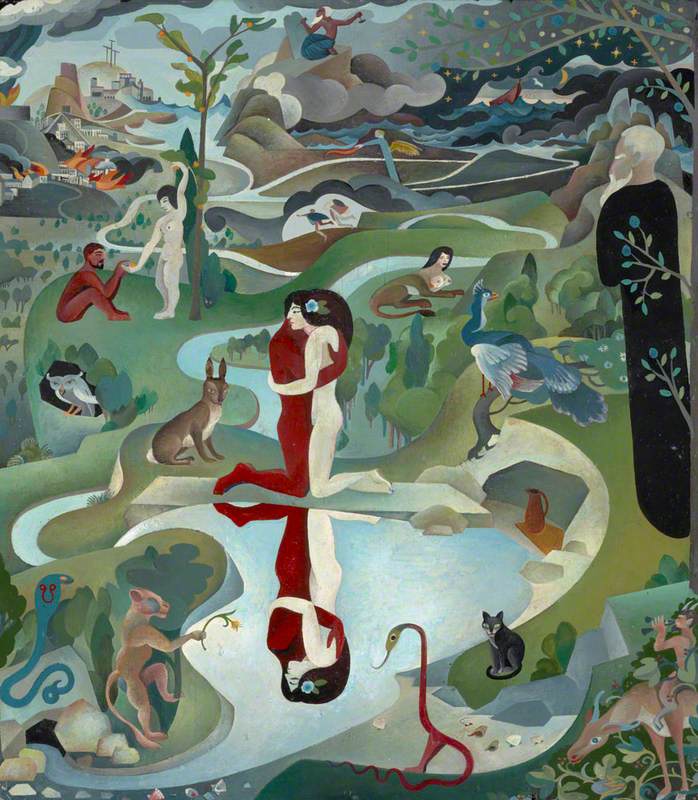

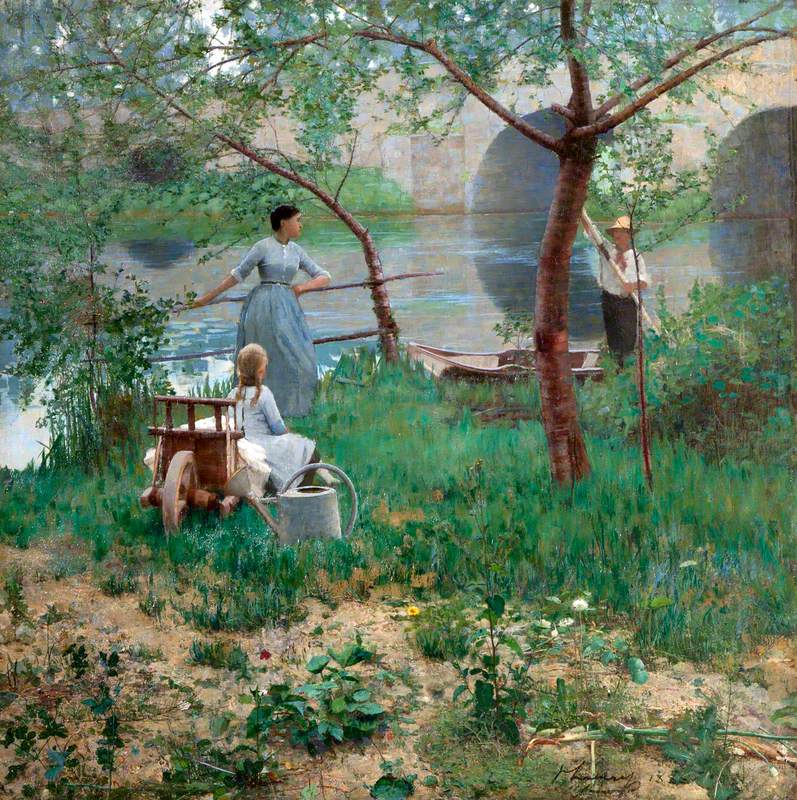

Under A Cherry Tree (1884) documents this phase of Lavery's development. Whilst in France he spent time at the artists' colony at Grez-sur-Loing, on the outskirts of the Fontainebleau Forest, associated with Realist landscape painting since the days of the Barbizon School.

Under the Cherry Tree

(previously known as 'On the Loing, an Afternoon Chat') 1884

John Lavery (1856–1941)

The painting shows a group of rural workers at leisure on the banks of the Loing, and is characterised by the same combination of vivid colour and figurative accuracy with patches of blocky or hazy abstraction as many of Bastien-Lepage's rustic genre scenes. (Another work from the Fleming-Wyfold Collection, The Bridge at Hesterworth, Shropshire, shows Lavery applying French plein-eir techniques to the British countryside.)

On his return to Glasgow, Lavery's reputation and client base grew until, in 1888, he was commissioned to paint Queen Victoria's visit to the Glasgow Exhibition, on the strength of a series of sketches of the exhibition grounds created earlier in the year. The Blue Hungarians (1888) dates from this period, its enigmatic title referring to the group of visiting musicians entertaining the crowd on the central bandstand.

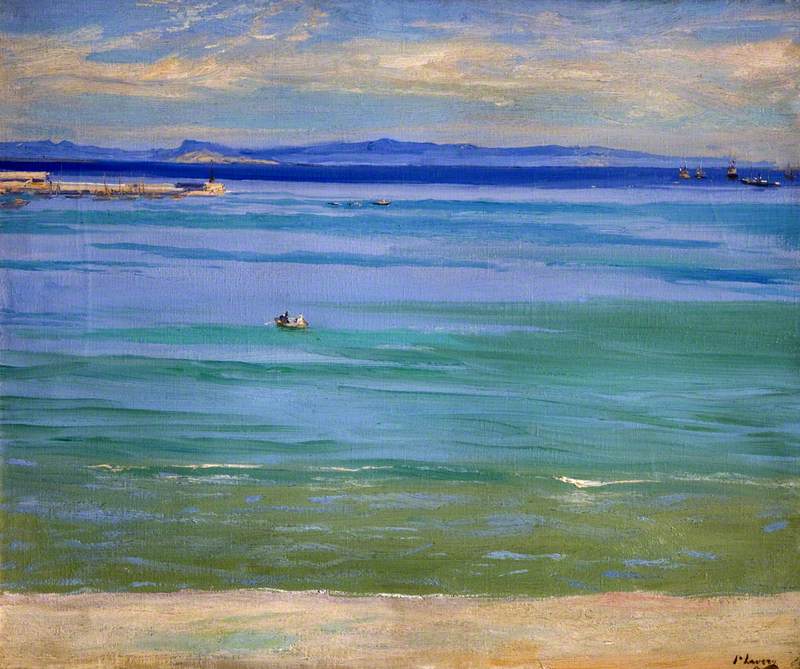

This work indicates Lavery's debt to the other great lodestar, besides Bastien-Lepage, of the Glasgow School: the American-born Impressionist James Abbott McNeill Whistler. Whilst he never adopted the sultry tonality of Whistler's palette, in works such as The Blue Hungarians, Lavery was clearly experimenting with the almost liquid quality of Whistler's landscapes, individual bodies picked out as translucent yet arresting details.

Lavery's painting shows an aptitude for change, and an openness to new contexts and themes, that matched his extraordinary biography. As a man and as an artist, this openness was almost always to his credit, and is difficult not to like.

Greg Thomas, writer and editor

A version of this article was originally published by The Fleming Collection