A recent re-hang at Christchurch Mansion in Ipswich sees a brooding landscape by Jacob van Ruisdael (1628/1629–1682) hung alongside the Constables and Gainsboroughs for which the collection is best known. It is striking to see just how much the older Dutch artist inspired the development of an English landscape tradition.

The idea of landscape as a subject in its own right began to emerge in Flemish art soon after the reformation. The art market shifted dramatically from religious commissions for churches, cathedrals and pious individuals to the newly emerging merchant classes who required art for their homes. Their new wealth was spent on portrait and still life subjects as well as land and seascapes. The hard-working citizens of cities like Amsterdam and Antwerp became passionate collectors of art filling their homes with paintings and prints. This allowed artists such as Rembrandt van Rijn and Peter Paul Rubens to become rich and influential in what became known as the Dutch Golden Age. Landscape became a popular genre of which Jacob van Ruisdael was a master.

Image credit: Colchester and Ipswich Museums Service: Ipswich Borough Council Collection

Jacob van Ruisdael (1628/1629–1682)

Colchester and Ipswich Museums Service: Ipswich Borough Council CollectionRuisdael's Path Through a Wood is a painting full of darkness. The trees have a deeply rich tone, the path is shadowy and the clouds are heavy and grey. It feels as though the weather is about to take a turn for the worse. Two small figures make their way along a muddy track. A strong wind seems to unsettle the scene. You can almost hear the brittle whisper of the leaves in the trees as the branches quiver. There is a vivid glimpse of blue sky through the threatening clouds. The blue sings like a bird in the dark woodland. The whole scene is alive.

It is fascinating to see this painting alongside works by the two giants of East Anglian art. The English landscape tradition was deeply influenced by the Dutch masters of previous centuries. Ruisdael, Meindert Hobbema, Jan Wijnants and other painters of the Dutch Golden Age had become very collectable in Britain in the eighteenth century. Gainsborough and his contemporaries would have had the opportunity to view these works in their wealthy patrons' houses as well as the salesrooms and auction houses of London. Also, the printmaking tradition which flourished in Holland created a much wider audience for their work, allowing artists to collect these works as well.

Image credit: Colchester and Ipswich Museums Service: Ipswich Borough Council Collection

The Mill Stream, Willy Lott's House 1814–1815

John Constable (1776–1837)

Colchester and Ipswich Museums Service: Ipswich Borough Council CollectionThe countryside and rural way of life was a subject close to the heart of the English, so it was no surprise that artists intensively studied the new 'landskips' arriving in the country. They absorbed lessons about composition and atmosphere, moving their art beyond the merely topographical. John Constable very carefully copied etchings by Ruisdael even to the point of reproducing his signature.

Soon enough, a uniquely British vision began to emerge. Collectors were keen to see their own local landscapes and traditions in the art on their walls and British artists were keen to depict the world around them.

Image credit: Colchester and Ipswich Museums Service: Ipswich Borough Council Collection

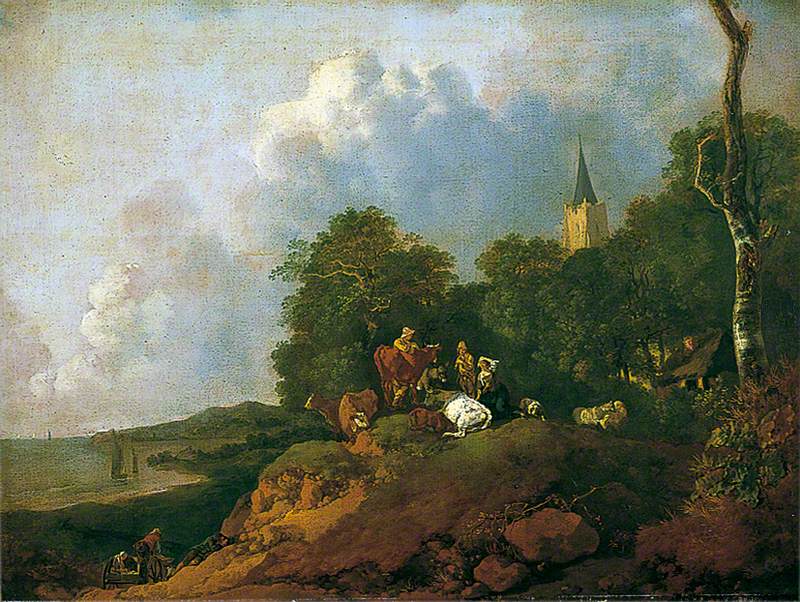

Holywells Park, Ipswich 1748–1750

Thomas Gainsborough (1727–1788)

Colchester and Ipswich Museums Service: Ipswich Borough Council CollectionBoth Gainsborough and Constable were deeply affected by the landscape of Suffolk, their home county. Gainsborough regularly painted and sketched the fields and woodlands around Sudbury and Ipswich in his early years. A local market developed with Gainsborough receiving commissions from the likes of the Cobbold family whose wealth stemmed from banking and brewing businesses. They commissioned a view of Holywells Park which captures a sense of the clear bright light of East Anglia combined with a clarity of observation.

Image credit: Colchester and Ipswich Museums Service: Ipswich Borough Council Collection

Thomas Gainsborough (1727–1788)

Colchester and Ipswich Museums Service: Ipswich Borough Council CollectionHis later landscapes took on a more sentimentalised view of the countryside. His 'Fancy Pictures' were developed from imagination and models. The brushwork became more fluid and energetic creating a nostalgic atmosphere of idealised peasant life which proved hugely popular in his time.

Image credit: Colchester and Ipswich Museums Service: Ipswich Borough Council Collection

Golding Constable's Flower Garden 1815

John Constable (1776–1837)

Colchester and Ipswich Museums Service: Ipswich Borough Council CollectionThe young John Constable was fascinated by Gainsborough. He was encouraged in his interest by George Frost who was an Ipswich artist and drawing master.

Image credit: Colchester and Ipswich Museums Service: Ipswich Borough Council Collection

Ladies in the Mall (copy of Thomas Gainsborough) c.1820

George Frost (1745–1821)

Colchester and Ipswich Museums Service: Ipswich Borough Council CollectionFrost owned drawings and paintings by Gainsborough which the budding artist was able to study at close hand. The two artists went out on sketching trips which followed in the footsteps of Gainsborough. Together they explored the banks of the River Orwell and the countryside around Ipswich, tracking down the viewpoints that Gainsborough had earlier worked from.

Be transported to London with Thomas #Gainsborough's "Mall in St. James's Park." Watch the newest episode of "Travels with a Curator" now at https://t.co/lLCyIeb78n.

— The Frick Collection (@frickcollection) August 29, 2020

—

Thomas Gainsborough, The Mall in St. James's Park, ca. 1783. Oil on canvas #FrickCollection pic.twitter.com/OoG7QjO9Kr

Frost owned The Mall in St James Park, a substantial oil painting by Gainsborough which is now in The Frick Collection in New York. He hung it in his small home on the Common Quay in Ipswich and proceeded to create a slightly smaller copy of it in order to learn further about Gainsborough's methods of working. For a while, the two paintings hung together in the drawing room of their house in the midst of the busy port of Ipswich and the copy is now part of the Ipswich collection. Whilst Frost remained a significant local artist, it was Constable who came to define the way we look at the English landscape.

The debt owed by the likes of Gainsborough, Constable, Cotman and Crome to their Dutch precursors is well highlighted in this exhibition. The painting by Jacob van Ruisdael arrived in Ipswich's collection in 2015 as a gift and has rarely been seen in public. The placement of Path Through a Wood here creates an intriguing dialogue about art on either side of the North Sea; how the example of Dutch brilliance laid the groundwork for English genius in landscape painting in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Michael Sheehy, illustrator, musician and Museum Assistant, Colchester and Ipswich Museums Service

'Recreating Constable' is at The Wolsey Art Gallery in Christchurch Mansion, Ipswich from 7th May to 25th September 2022