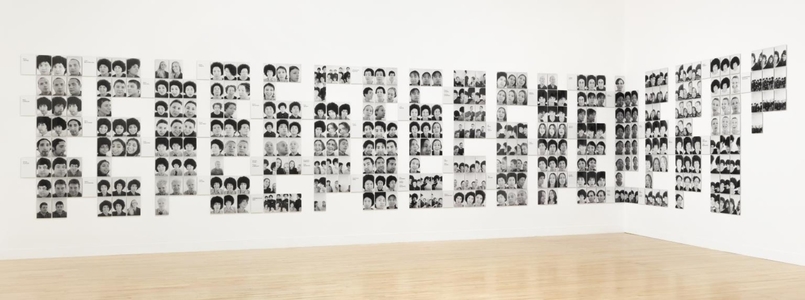

The peoples of the African diaspora have been represented in British art from around the seventeenth century to the current day; the colonial influence is the undercurrent of many of the works that are present in the museums and art galleries of Britain. The white gaze is the unlabelled and ever-present curator of British art, especially relating to the depiction of people originating from the African continent.

Ideas of privilege, power and history cannot be separated from the white gaze on Black bodies, and art is the construction of creative cultural commodities.

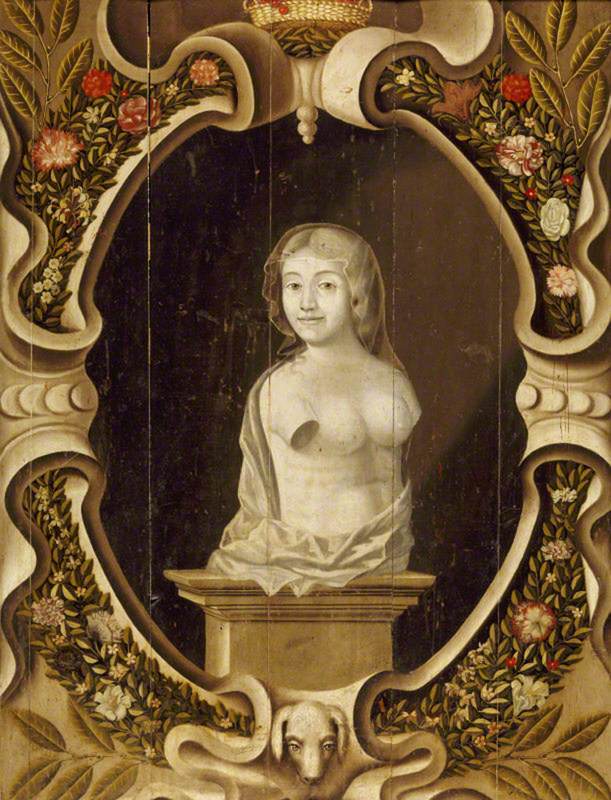

Africa, Personified by a Simulated Bust in an Ornamental Niche

mid-17th C

British (English) School

Africa, Personified is a mid-seventeenth century bust of a female figure. She is surrounded by a floral arrangement, while the torso is bedecked in a string of pearls, and the close-cropped hair is adorned by two pearl drop earrings.

The figure is gazing demurely to one side with unseeing eyes; this is an allegory for the African continent as the 'other', as seen through the colonial lens of European invaders. This work perfectly represents the emotions and ideas of the early colonial British sensibility, wherein Africa is feminised and infantilised, and its people are deemed to look the other way while the British raze the continent of its treasures, people and derail its future.

The bust of Africa, Personified can therefore be seen as an early representation of the commodification of places and people originating in Africa as chattel, or property.

Summer, Personified by a Simulated Bust in an Ornamental Niche

mid-17th C

British (English) School

In contrast to Summer, Personified, the Africa bust features a strangely disproportioned figure – akin to a child presented as an adult – that is placed naked with the exception of a feathered loin covering, and positioned atop a fierce-looking elephant. The Summer bust, however, shows a taller torso of a beatified white European woman, draped in curled locks of hair, swathed in soft flowing material on an enlarged plinth.

The complete set of 'Personified by a Simulated Bust' series also includes Asia, Winter, America and Europe.

America, Personified by a Simulated Bust in an Ornamental Niche

mid-17th C

British (English) School

As art is the generation of archetypal societal products, the America bust, along with the Africa one, shows naked indigenous women clothed in pearls and a garland of animal feathers, while Europe, Personified shows a figure reminiscent of Caesar, complete with a laurel wreath, front-facing the artist, atop a powerful bull.

Europe, Personified by a Simulated Bust in an Ornamental Niche

mid-17th C

British (English) School

The inclusion of the coded Africa, Personified image in the set reproduces racist iconography and political propaganda designed to convey a message of European superiority, and clearly shows how the white European gaze of the artist imagined the rest of the natural world and continents.

Artists' impressions of people around the world were the most popular media for sharing visual ideas before the introduction of mass photography in the nineteenth century.

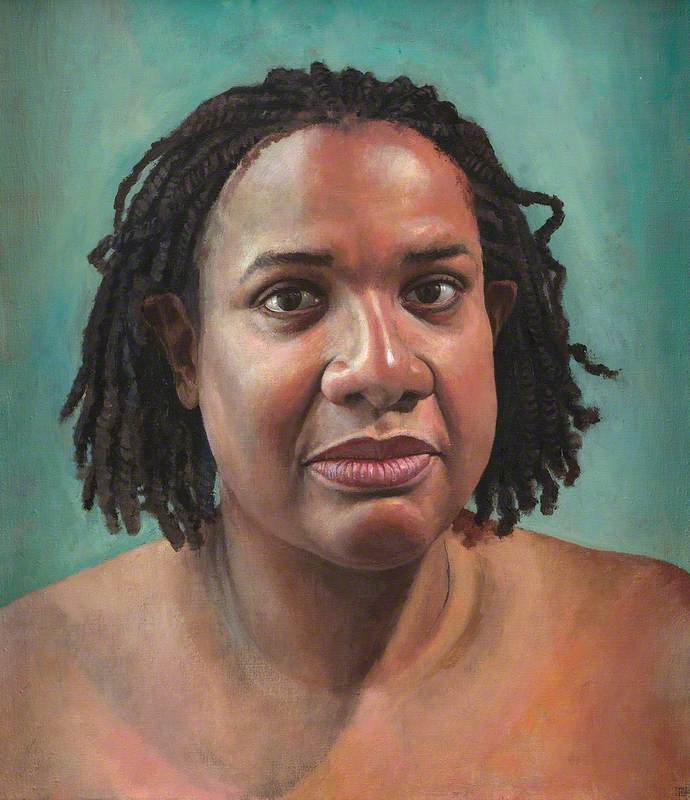

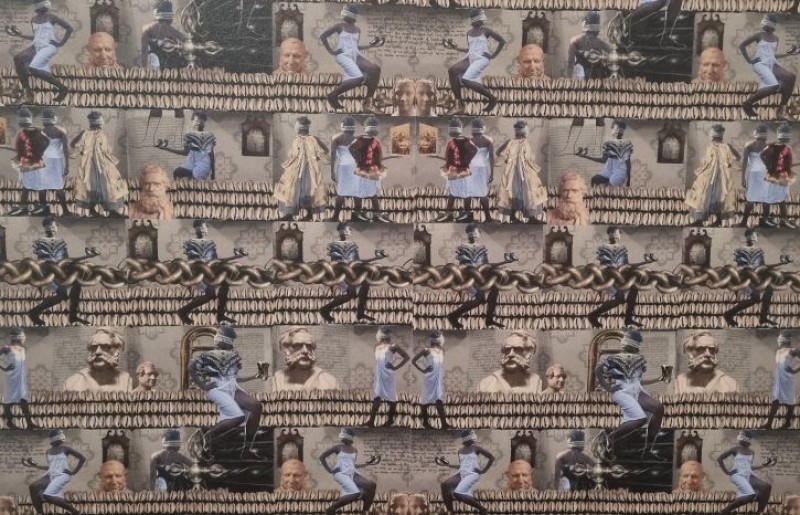

The seventeenth-century art collection of the 'Personified' series of busts can be compared with a twenty-first-century depiction of Diane Abbott MP.

At the unveiling of the painting of Diane Abbott in 2004, Tony Banks MP, Chairman of The Speaker's Advisory Committee on Art, said, 'This will prove to be an historic portrait of a contemporary Member of Parliament. As the first black woman MP, Diane Abbott's membership of the House is an important event in the history of Parliament.'

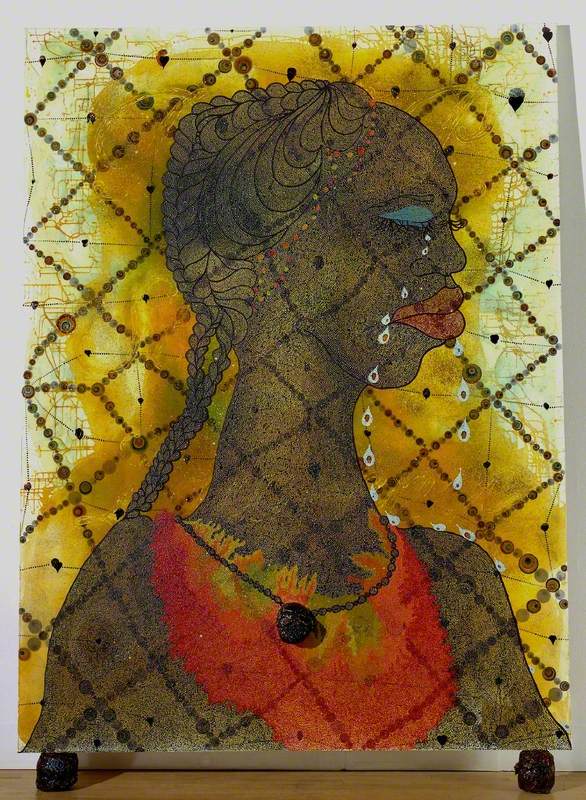

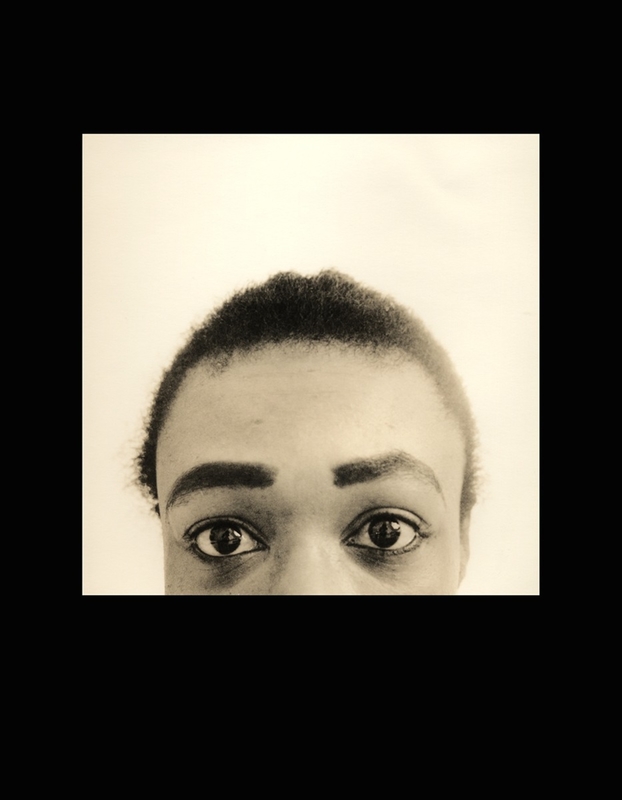

This painting shows Abbott portrayed akin to the bust of Africa, Personified, unclothed from chest upwards: it is the only portrait in the entire Parliamentary collection where the subject is depicted without clothing. Abbott speaks about her experience being painted in the below video.

Abbott chose the close-up portrait to disrupt the traditional parliamentary images because she knew it would hang among peer portraits of mainly white male MPs wearing suits; although Abbott subverts the traditional dress code of MPs, her painting still retains the white male gaze as the silhouette of the painter is depicted in her eyes.

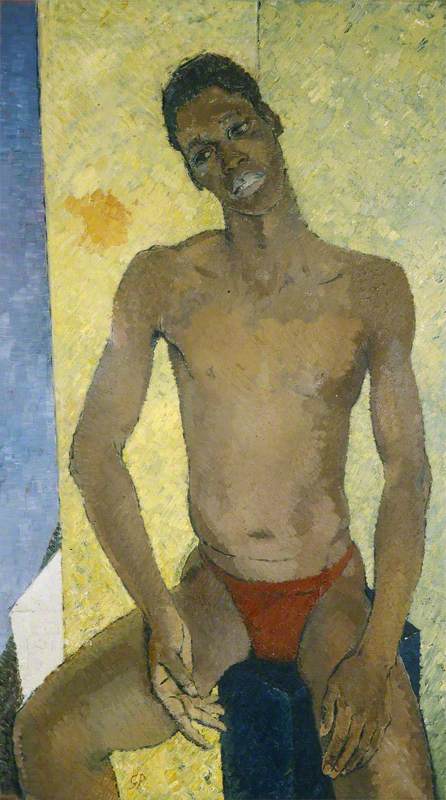

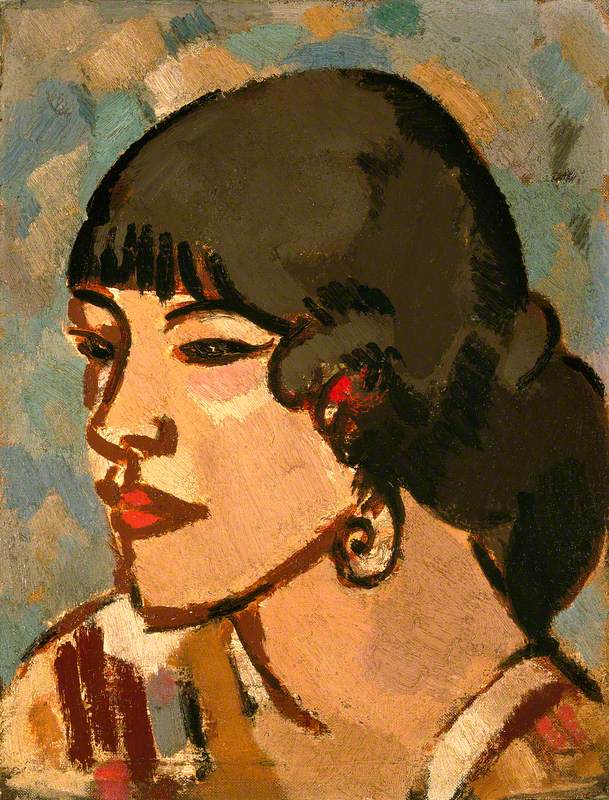

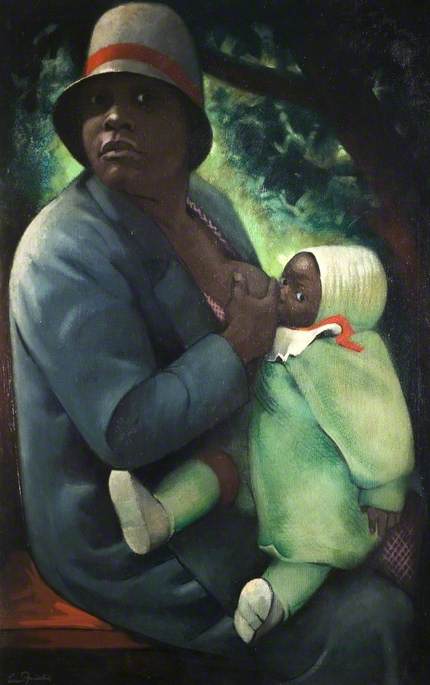

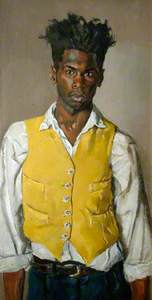

Glyn Warren Philpot's Portrait of Henry Thomas, a Jamaican Man (c.1935) was originally titled Head of a Negro by the white British artist, thus objectifying the sitter as an ethnic token.

Portrait of Henry Thomas, a Jamaican Man

c.1935

Glyn Warren Philpot (1884–1937)

However, it was retitled by Bristol Museum and Art Gallery (BMAG) with Henry Thomas' name to make it more accurate – Thomas was well known to Philpot because of their personal relationship.

It is not known if the original erasure of Thomas' name was to protect the relationship of the two men, in a period when homosexuality was deemed criminal, or if Philpot was merely cataloguing the image as he viewed it as a white artist: a negro man.

BMAG also revised the historic title of this painting to respond to the debate around the use of the word 'negro', which was historically and commonly used as a part of the dehumanising racism that is a foundation of the colonial mindset and British Empire.

Henry Thomas was Philpot's servant and companion from 1929, and his model for all sketches and portraits of Black men between 1932 and the artist's death in 1937; Philpot had a homoerotic fascination with Black men and when he travelled to Paris and America he would visit jazz clubs for entertainment and to find more subjects for his art.

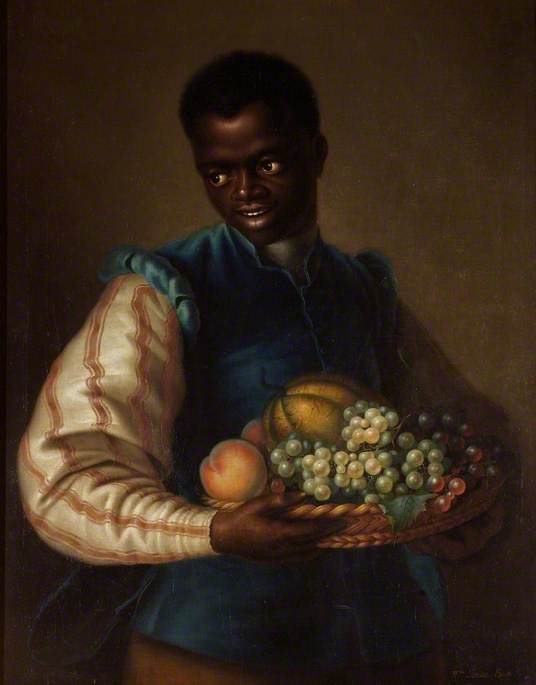

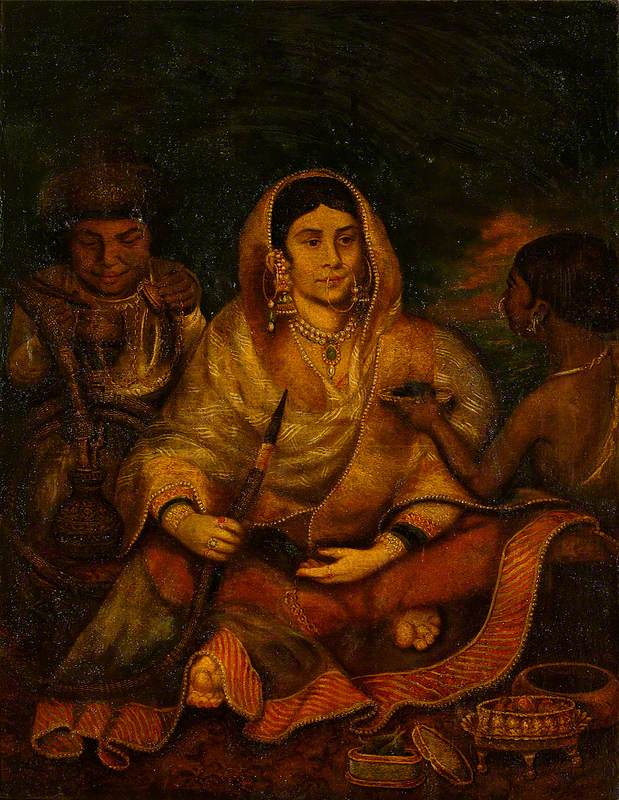

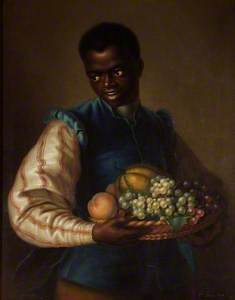

Along with the early propaganda portraits of the seventeenth century, Black people have been portrayed in the shadow of paintings of later years as servants, or maids or dismissively, unnamed and simply titled as the 'African', 'negro' or 'black boy'.

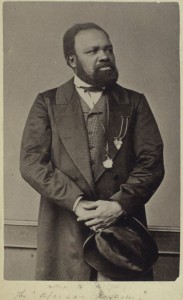

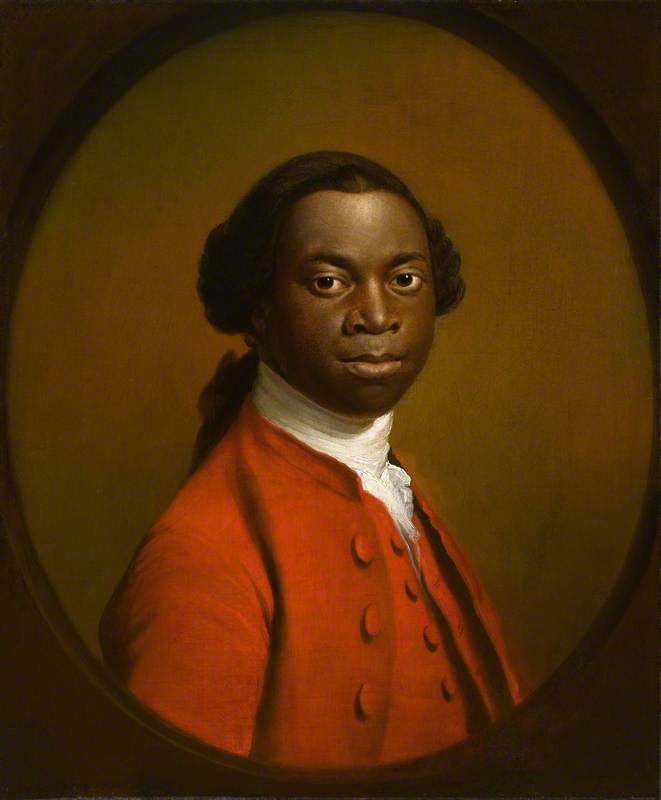

Misnaming subjects in paintings is also a regular occurrence, one that Paterson Joseph vehemently took offence to regarding Portrait of An African (attributed to Allan Ramsay), which was bracketed with 'probably Ignatius Sancho'.

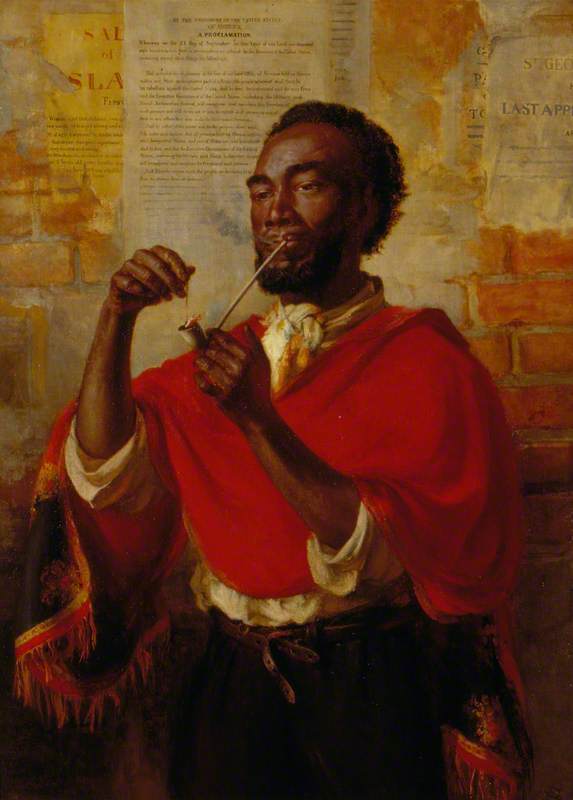

Portrait of a Man in a Red Suit

(formerly 'Portrait of an African') c.1740–1780

unknown artist

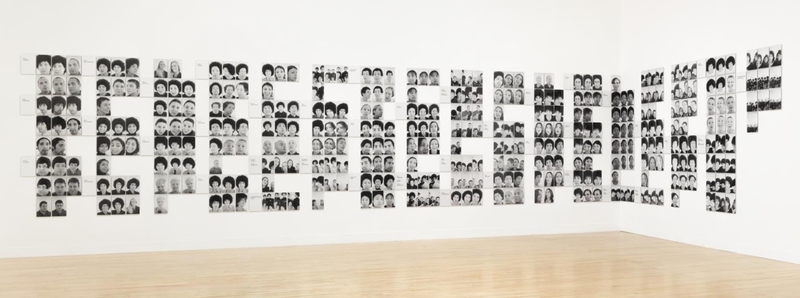

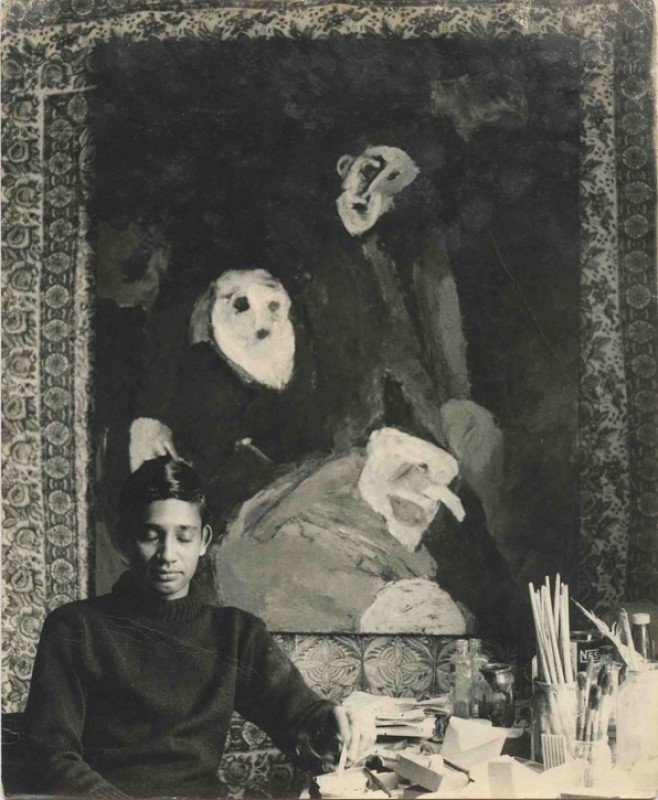

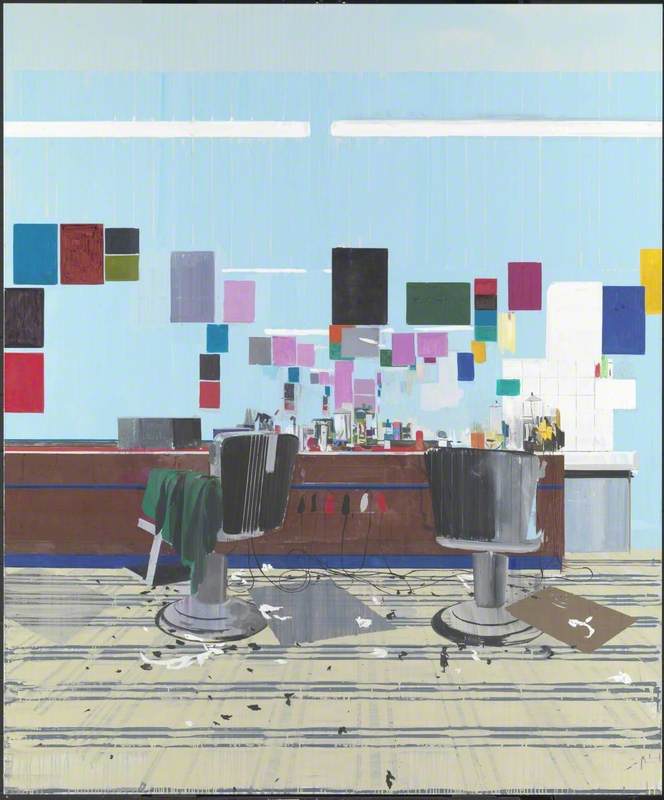

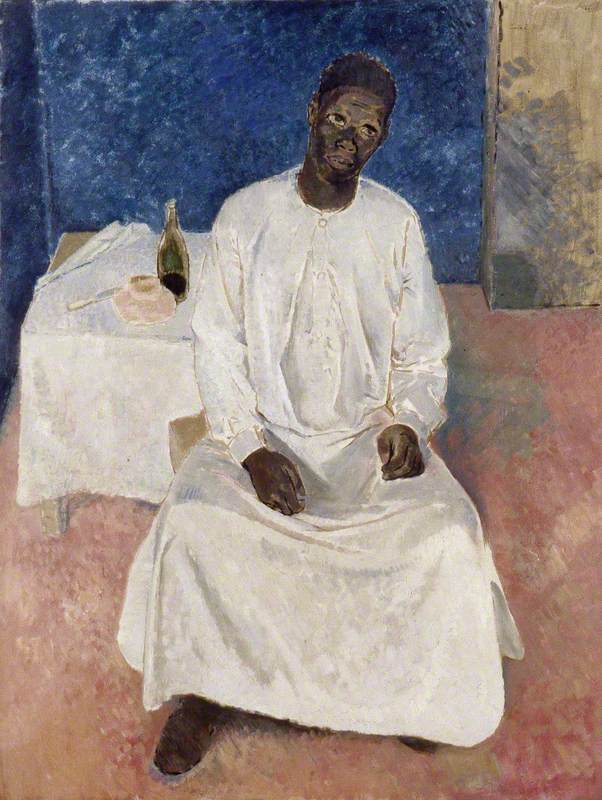

In the early portraits of the twentieth century, it can be seen that British artists of colour have had to juggle the heavy weight of their own history, their own body, and their own aesthetic balance against the cultural violence of the whitewashed artistic establishment.

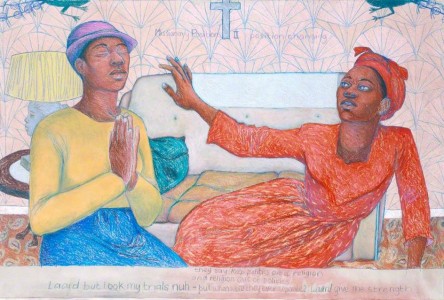

Art by British artists of colour reflects identity and aesthetics through an internal Black gaze, and starkly contrasts with the external white gaze of previous centuries; this art is personal rather than merely capitalistic or colonial.

Similarly, the art of projecting self-identity communicates the perception of empowerment and enterprise. This furthermore resets the artistic gaze from the whiteness of British, paternalistic, colonial capitalism to the individuality of the multi-faceted Black British identity – this is a viewpoint that acknowledges, embraces, and names all aspects of the Black body in time through history.

In twentieth-century art and beyond, Black British artists are seen meditating, defining, and curating the joyful representation of the relationship between their bodies, their histories, and their artistic practice while subverting the gaze on their skin through the medium of their own eyes. On their own aesthetic terms, they move away from the binary representations of white being equated with good and black being associated with evil.

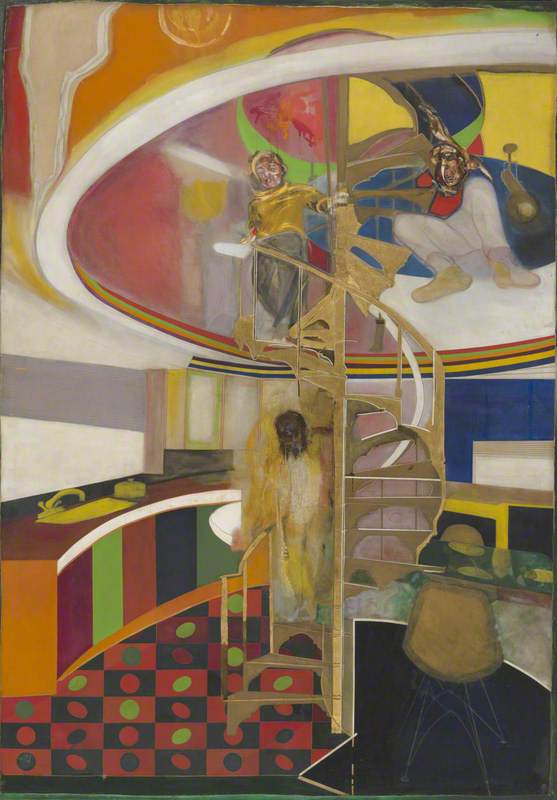

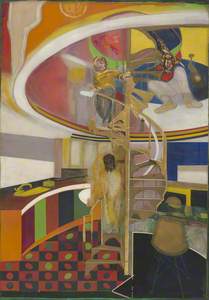

In Mirror, Frank Bowling explores the concept of an artist catching a glimpse of themselves in the mirror while walking by, but also realising that one is in fact locked in to the performance and presentation of self.

Mirror shows the conflict and tension in the work of being an artist and portraying a true sense of identity so Bowling depicts himself twice: once using disfiguration and a sense of being split off from himself at the top of the staircase, as he is escaping and rising to great heights to access an entry point into the arts and culture world. He paints himself in the work again, at the bottom of the painting, where his character disappears in an attempt to avoid the critical gaze of others.

This self-portrait from Bowling colourfully, and with the use of different painting styles, makes an introspective statement about perceived identity in direct opposition to the historical 'white gaze' of Black people in British and global artworks. Mirror depicts his attempt to explain the image of himself but still have a presence in his art.

Bowling makes the gaze personal, he turns it outwards, bringing a different level of visibility and stature as he reflects his internal identity on the canvas for all to see the conflict and confusion of his self-image.

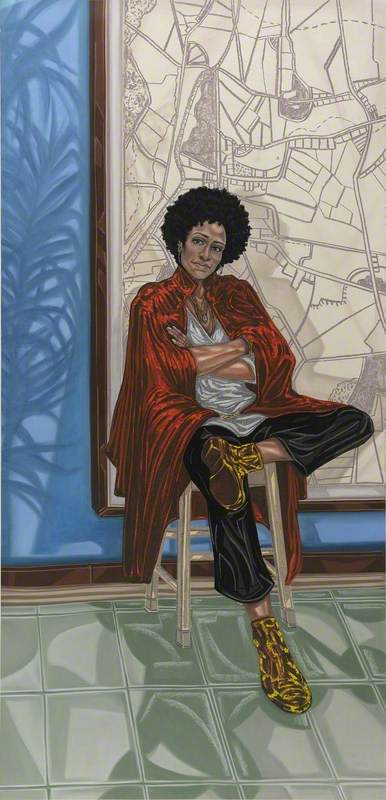

Artists like Frank Bowling, Sonia Boyce, Lubaina Himid, Desmond Haughton, and Chris Ofili use portraits and self portraits to reset the ways of seeing and being seen.

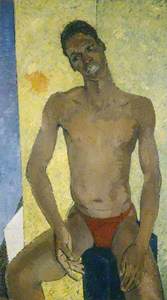

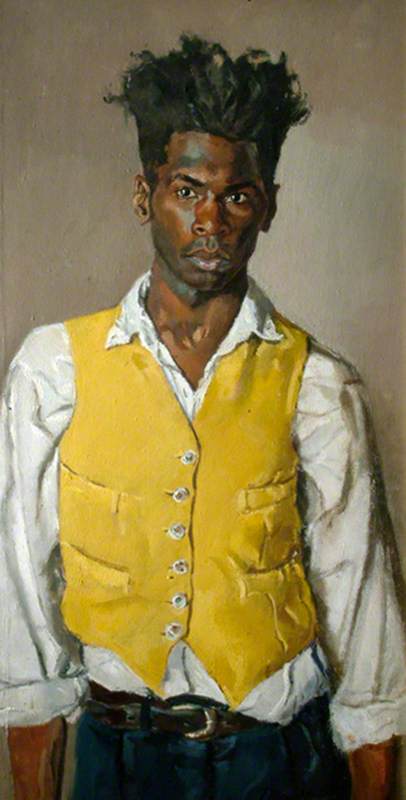

Self Portrait in a Yellow Waistcoat

1993

Desmond Haughton (b.1968)

Self portraits are revolutionary, as they change the establishment view of a particular identity and invite all viewers to see differently, to have empathy, and to respect the difference on show.

Marjorie H. Morgan, playwright, director, producer and journalist