Historically, draughtsmanship has been an essential tool in the arsenal of any painter. For Frederic, Lord Leighton (1830–1896) pencil and charcoal sketches served the purpose of designing compositions for subject pictures as well as working out the poses of his figures and various details. They also allowed him to capture interesting sights during his extensive annual travels.

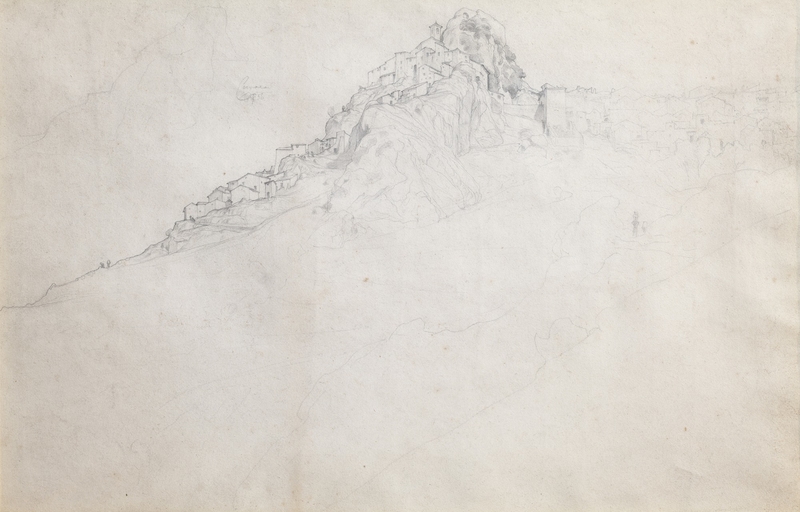

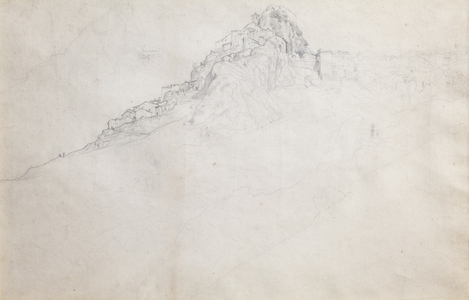

View of the Town of Capri, Italy

1859

Frederic Leighton (1830–1896)

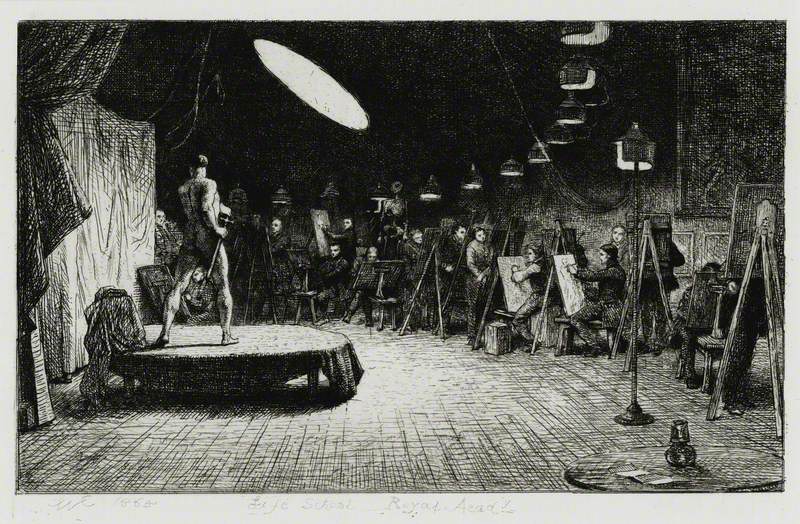

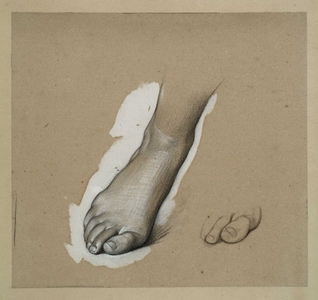

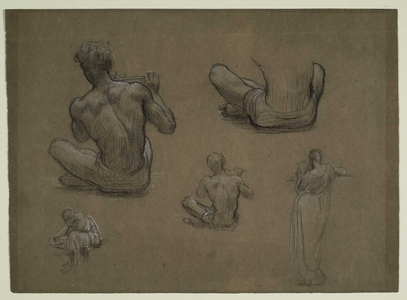

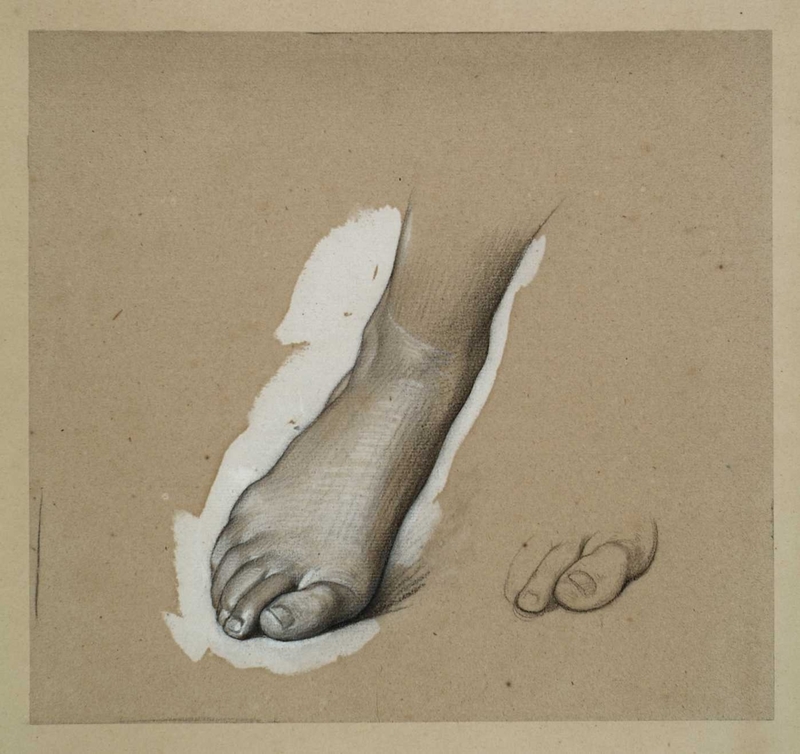

Although Leighton was elected President of the London Royal Academy of Arts in 1878, he did not receive his training from this institution. In fact, he had not trained in Britain at all. Between 1846 and 1852, with some breaks spent in Brussels and elsewhere in Europe, Leighton studied at Frankfurt at the Städelsches Kunstinstitut, where he received his core formal training. In addition to making studies from plaster casts of ancient sculptures, at Frankfurt a more liberated approach allowed even the youngest students to draw from life models in the studio. Throughout his life, Leighton continued to practice both, the former emphatically demonstrated by the several casts he displayed in his studio, most notably a fragment of the Parthenon frieze.

Studies of a Foot and Toes

1850–1860

Frederic Leighton (1830–1896)

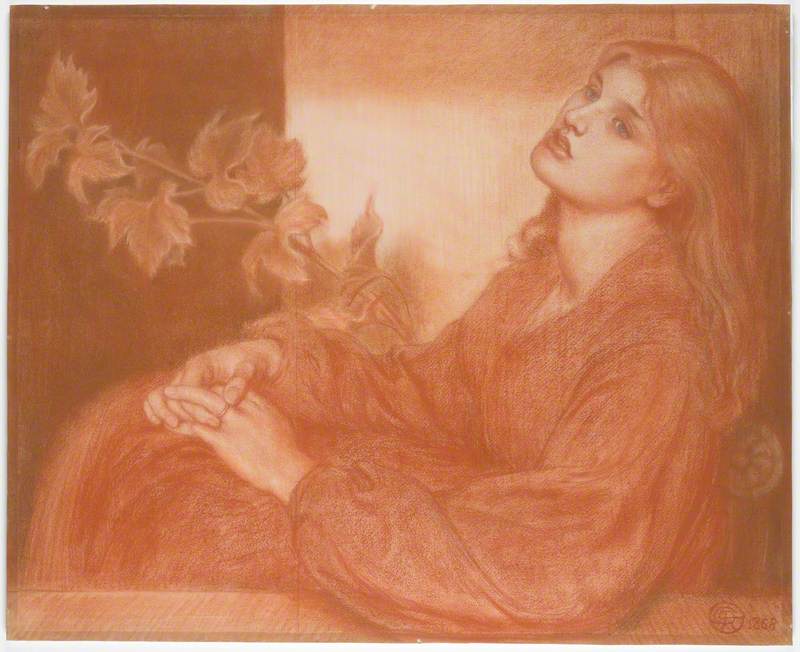

While several watercolour drawings and illustrations survive from his student days in Frankfurt, he rarely reached for this medium in later years. Charcoal, pencil and silverpoint studies dominate, often with highlights in white chalk. The fact that he did not seem to use the 'trois crayons' method of simultaneously utilising red, black and white chalk, or even a single sanguine chalk, attests that, for him, drawing was predominantly a means to an end: a study for an oil painting, rather than a potentially presentable work in its own right.

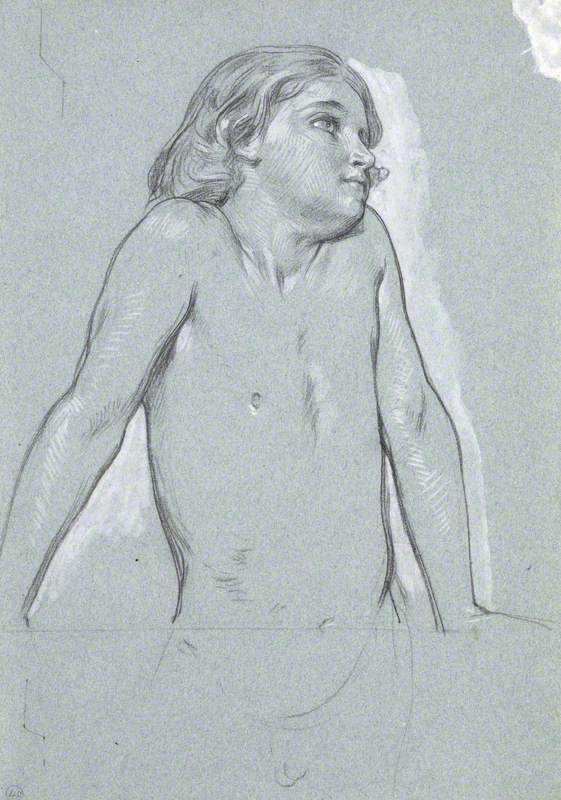

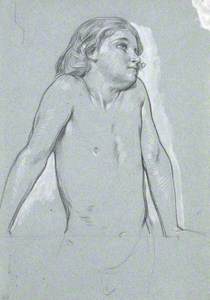

This is further evidenced by his preference for ordinary brown paper, of which large quantities, together with entire boxes of vine charcoal, he regularly requested from the artist's supplier Charles Roberson & Co. Nowhere in his Roberson account are there references to blue paper, although he did use it, mostly for life studies from models, such as this drawing of a nude young boy, whose contours he further enhanced with white wash.

Leighton drew regularly during his extensive voyages, particularly in his youth, although he was selective about his subjects. On his way from Frankfurt to Rome in 1852, Leighton reported: 'I felt the greatest possible reluctance to sketch in the hasty manner in which one does when travelling; I shunned the idea of approaching Nature in a manner which seemed to me disrespectful, and the consequence was that until I got to Verona I did not touch a pencil.'

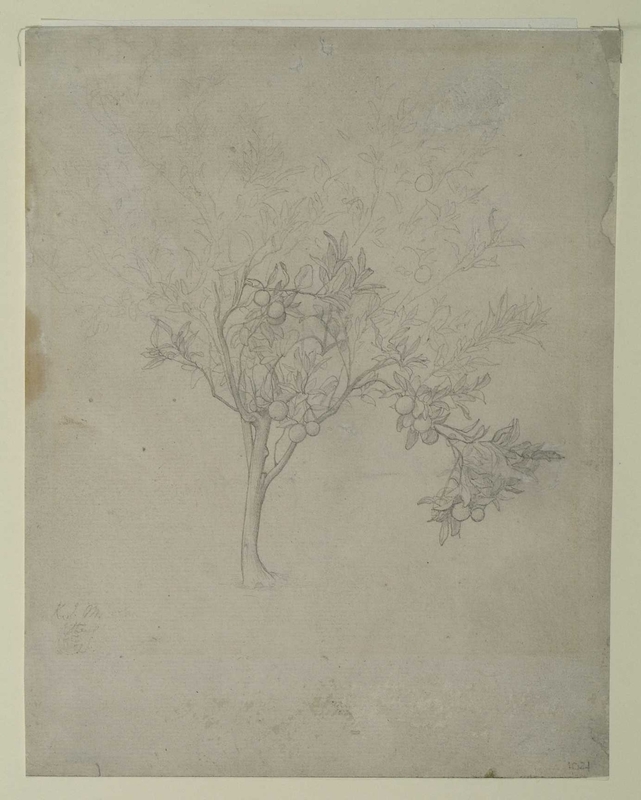

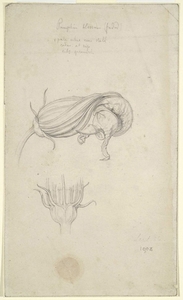

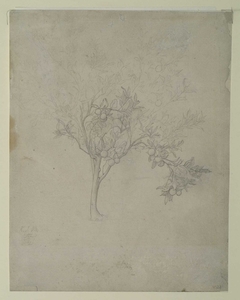

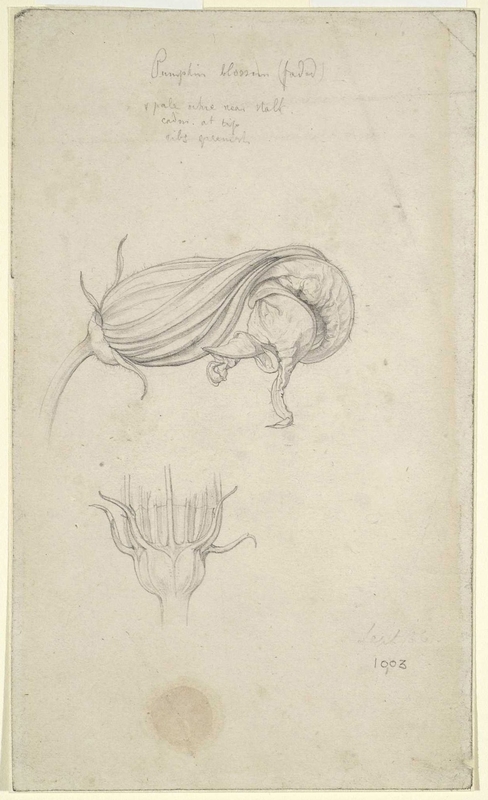

Studies of Pumpkin Blossoms

1856

Frederic Leighton (1830–1896)

This devotion to making meticulous and attentive studies from nature is most evident in such early drawings as his study of pumpkin blossom, almost scientific in its approach to observe the plant from various angles and to supply the visual representation with annotations of colour.

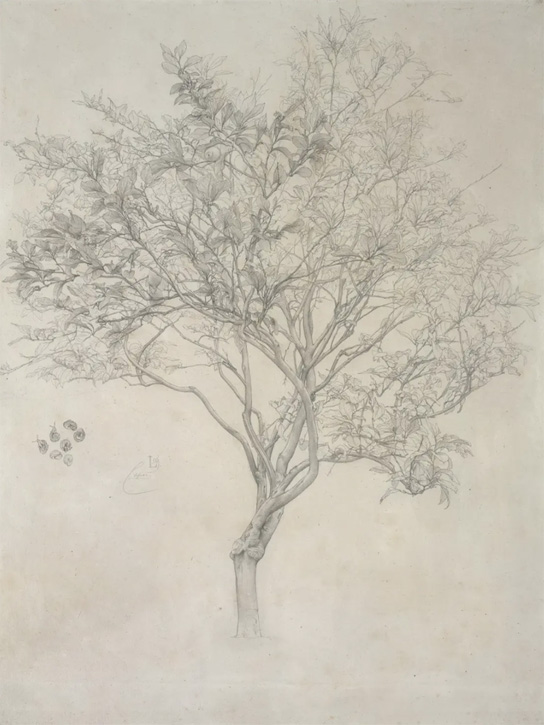

Among Leighton's most venerated botanical drawings, and reminiscent of this study of an orange tree from 1867, is The Study of the Lemon Tree (private collection, on view in 'Leighton and Landscape: Impressions from Nature' at Leighton House Museum until April 2025), conscientiously executed over a period of several weeks on Capri in 1859. It was later used by the influential writer and art critic John Ruskin to illustrate his Slade lectures at Oxford.

Study of a Lemon Tree, Capri

1859, drawing by Frederic Leighton (1830–1896)

While still living in Rome, Leighton was closely reading volumes by Ruskin, whose exhoneration to young painters to faithfully depict subjects from the natural world, 'choosing nothing and rejecting nothing,' deeply resonated with him. This, together with the training Leighton received from the German School which greatly emphasised draughtsmanship, resulted in a plethora of detailed and often annotated drawings produced in his youth – more inquisitive about nature than interested in the Antique.

A pencil study of the Italian hilltop town of Cervara, near Rome, dated to 1856 and complemented by a subsequent oil sketch, is a testament to the vastly different purposes of 'finished' pictures than those of open-air studies.

In this sketch, Leighton placed the outline of the craggy slopes directly below the upper edge, leaving the lower half of the sheet virtually empty. This technique emphasises the artist's lowered vantage point and the steepness of the tall mountain. The desired effect, therefore, was to evoke the scale, monumentality and perspective, rather than a symmetrically arranged composition, based on the conventional principles and directly leading to an exhibitable picture.

This is further evident in comparison with the second, upright and far more worked-up version of the subject in oils, populated with figures in the foreground (private collection, on view at 'Leighton and Landscape'), which Leighton completed in 1859 and gave to Nino Costa, Italian landscape painter whom he first met in 1853 during the annual artists' picnic held at Cervara.

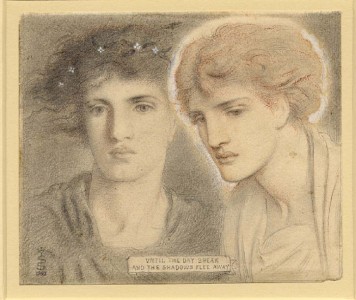

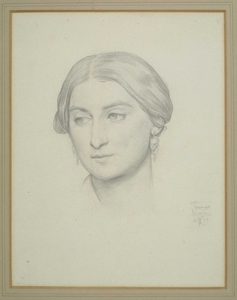

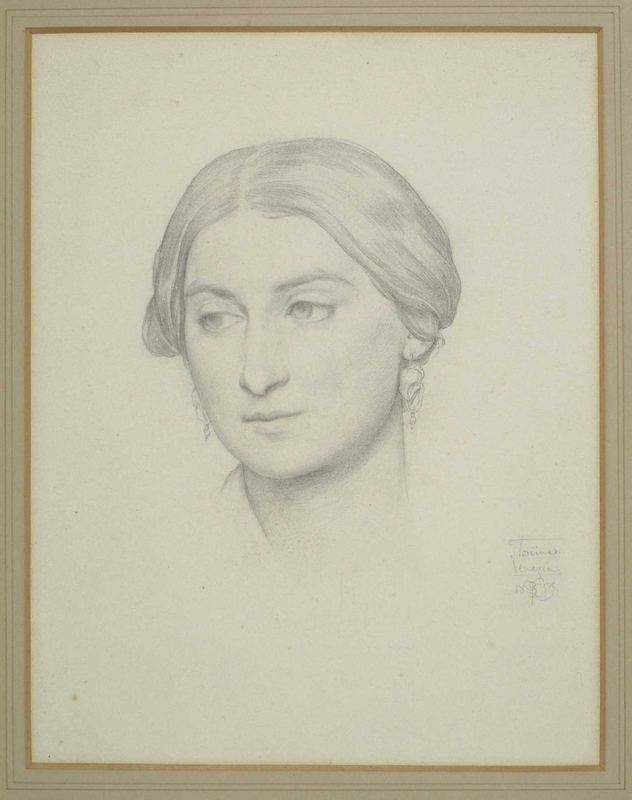

Study for 'Cimabue's Celebrated Madonna...': Female Head

1853

Frederic Leighton (1830–1896)

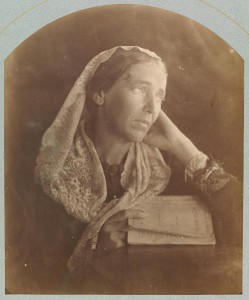

On his travels, Leighton also produced numerous head studies. Drawn in 1859 in Venice, on Leighton's way to Rome, this gently shaded portrait depicts an Italian woman named Tonina, possibly the wife of Nino Costa.

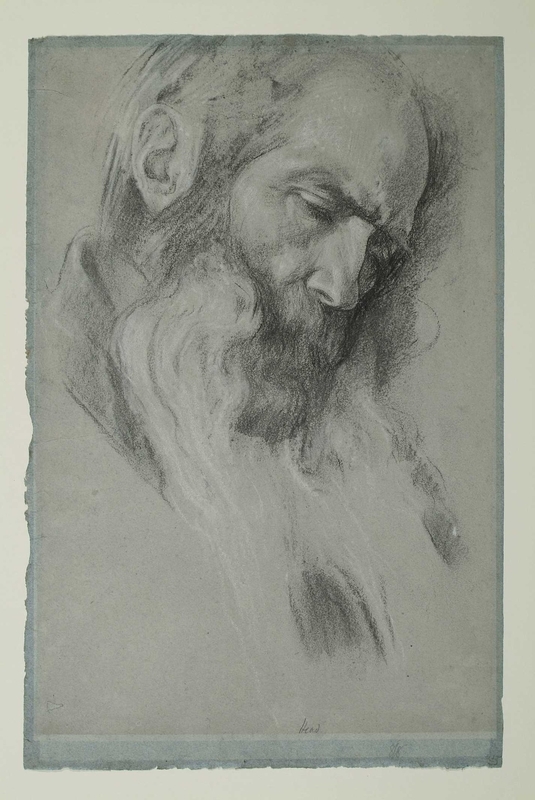

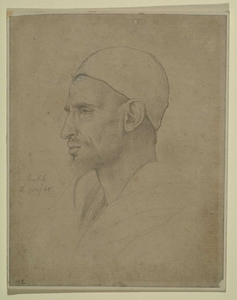

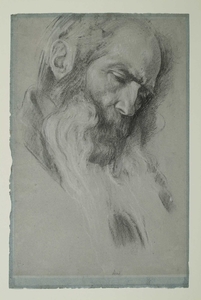

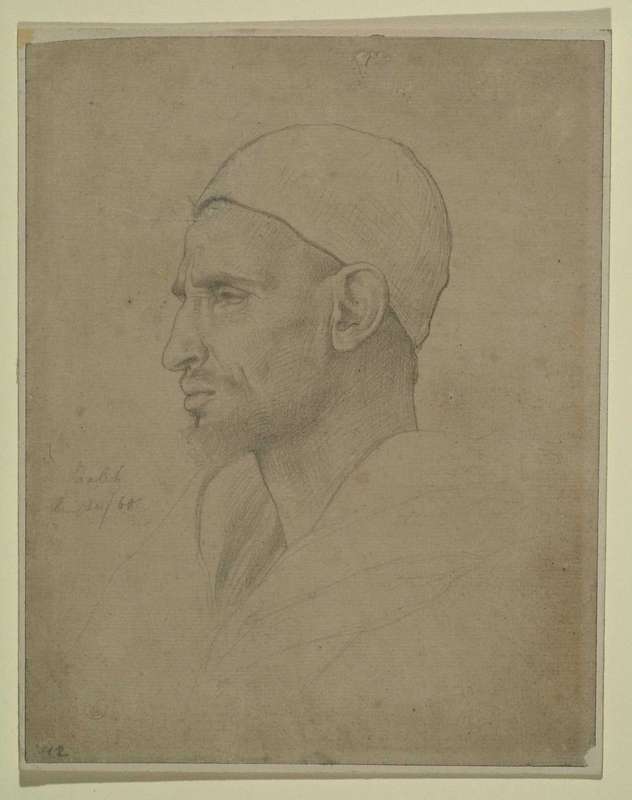

Study of a Male Head, Luxor

1868

Frederic Leighton (1830–1896)

Another named sitter, Jaleeh, was captured during Leighton's voyage up the Nile in 1868. Unlike the earlier refined study of Tonina, this drawing was produced much more swiftly, as seen in the clearly visible cross-hatching.

While in the studio Leighton often used various types of chalk, on his travels he largely relied on the more convenient pencils. His particular preference for the Pure Cumberland lead pencil resulted in it being known, and marketed, as the 'Leighton pencil' from around 1888.

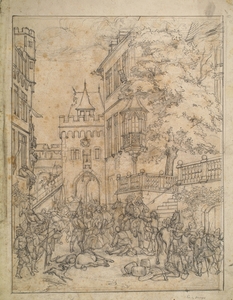

Study for a 'Composition Showing a German Town'

1845–1852

Frederic Leighton (1830–1896)

As his career developed, Leighton developed various steps for designing large-scale compositions for subject pictures. This detailed sketch is most likely the first version of Leighton's large watercolour picture Preparing for a Fiesta of 1851, which he produced as a student in Frankfurt. The archway in the above drawing inspired the architectural framing of the watercolour, yet this ultimately unutilised design represents Leighton's increasing shift from gothic, northern European settings to those of the Italian Renaissance, as he chose for the final picture.

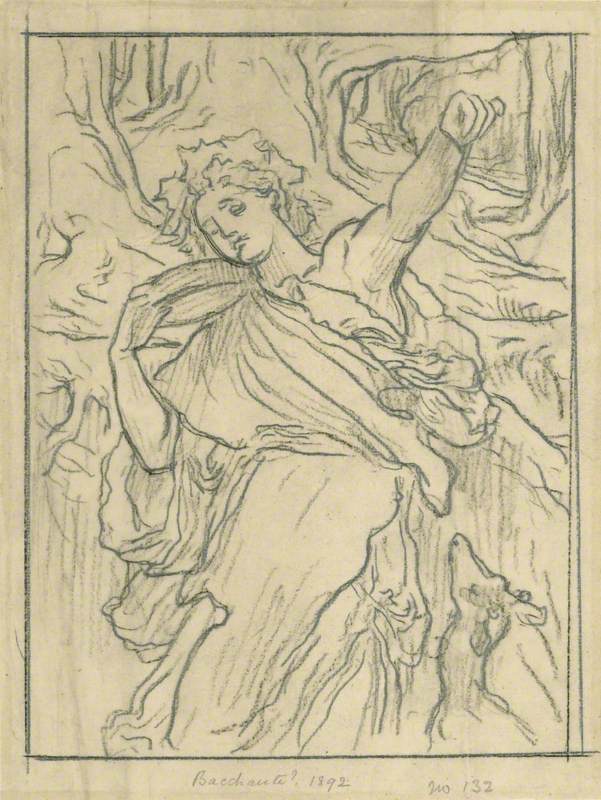

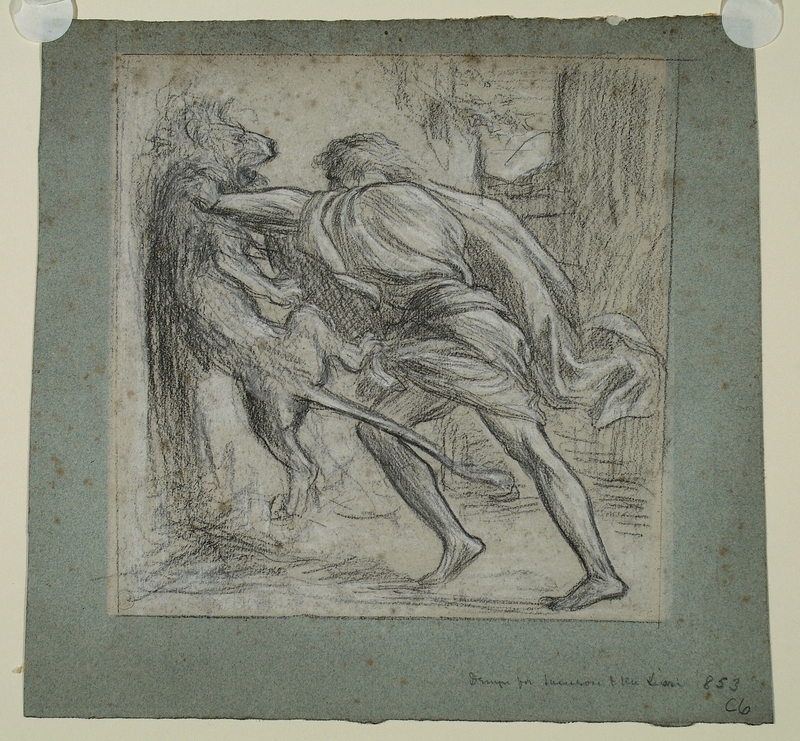

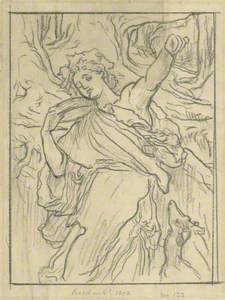

Compositional Sketch for 'Daedalus and Icarus'

1868 or before

Frederic Leighton (1830–1896)

After leaving Frankfurt for Rome in the 1850s, Leighton's modus operandi changed. He largely abandoned making such fine and exact designs for entire compositions, instead working out the necessary detail in individual studies. This hastily jotted composition sketch for Daedalus and Icarus, with prominent cross-hatching and vaguely suggested contours, shows a different way of working on large-scale subjects, where the overall design is only one of many steps in the process.

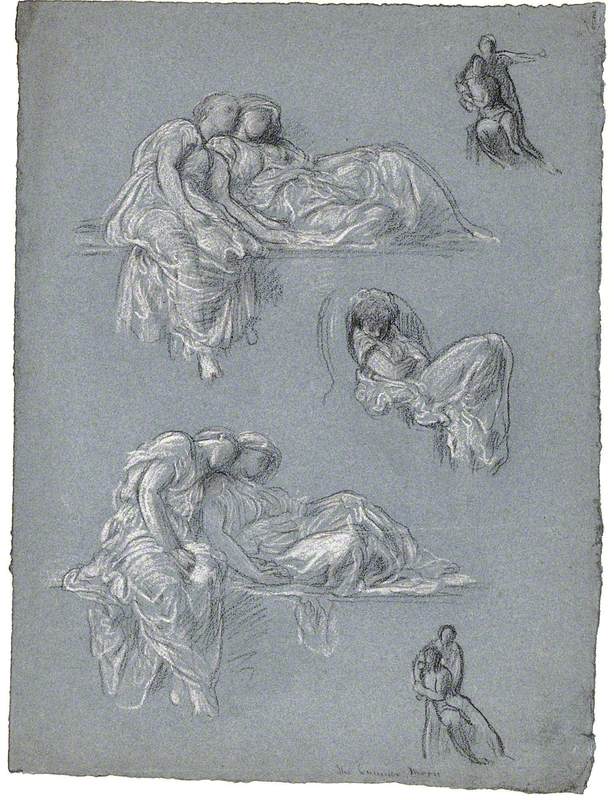

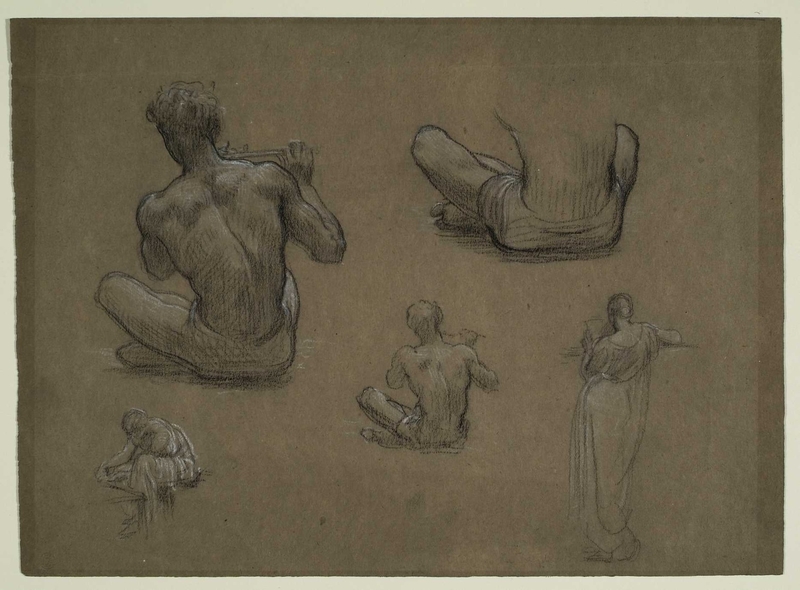

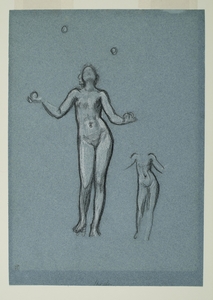

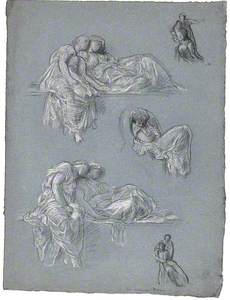

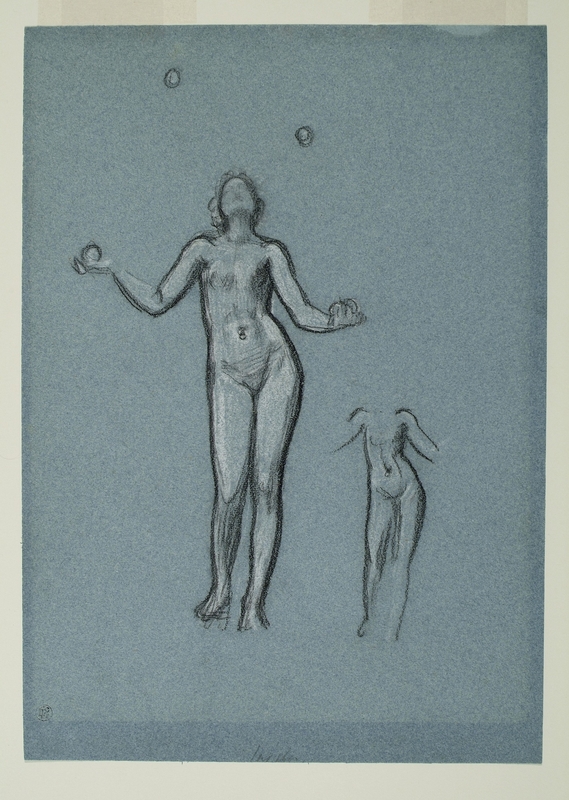

Studies for 'Antique Juggling Girl': Female Figures

c.1872

Frederic Leighton (1830–1896)

Once Leighton was satisfied with the general design, he proceeded to make studies from nude models, which he explained as necessary because once clothed in heavy draperies, the models could not retain the desired poses. In this exceptional case, the end result – the painting The Antique Girl Juggling (private collection) – is not dissimilar from the preparatory studies, as the titular figure bears only a thin veil draped around her hips.

Study for 'The Return of Persephone': Drapery for Demeter

c.1890

Frederic Leighton (1830–1896)

Once he had established the pose of the figure, Leighton moved on to meticulous studies of the draperies. In this preparatory drawing for The Return of Persephone, the body underneath the fabric is suggested by faint pencil outlines of the arms and feet.

On occasion, a closer study of a fragment of draped material was required, such as in this preparatory drawing for an unidentified composition. The dexterous use of white chalk for highlights creates here a highly voluminous and realistic effect of the folds draped on a figure's arm.

Following Leighton's death in January 1896, countless portfolios and sketchbooks were found in his studio and subsequently exhibited at the Fine Art Society. Such display of drawings, mostly auxiliary studies, was not unprecedented, as even the Royal Academy had been holding 'black and white' exhibitions from the 1870s. A wider survey of the products of Leighton's draughtsmanship demonstrates a carefully calibrated practice that was fundamental to the artist's way of working throughout his long career.

Dr Pola Durajska, co-curator of 'Leighton and Landscape' and Head of Pictures at Bearnes Hampton & Littlewood auctioneers

'Leighton and Landscape: Impressions from Nature', at Leighton House Museum, is on view until 27th April 2025

This content was funded by the Bridget Riley Art Foundation

Further reading

Philippa Martin, Alison Smith, et al., A Victorian Master: Drawings by Frederic, Lord Leighton, The Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, 2006

Daniel Robbins, Pola Durajska, et al. Leighton and Landscape: Impressions from Nature, The Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, 2024