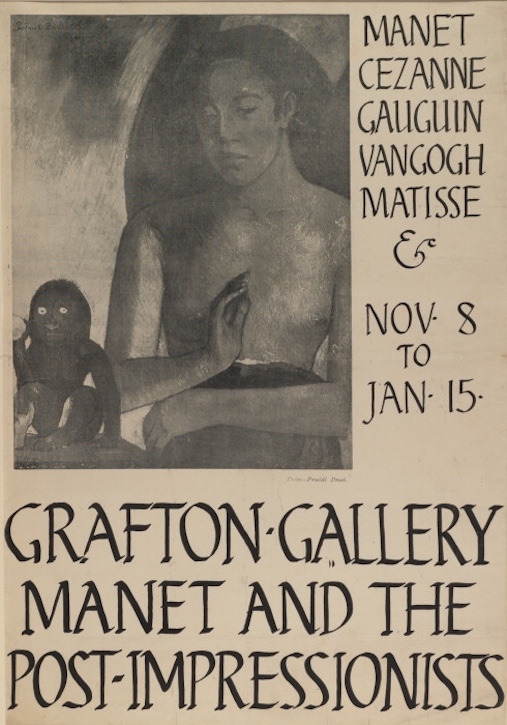

The beginning of the twentieth century was not an easy time to be a modern artist in Britain. Painter and critic Roger Fry memorably dubbed the nation the 'Bird's Custard Island' – a country populated by the culturally unsophisticated and the conservatively stodgy. In 1910 he organised an exhibition, 'Manet and the Post-Impressionists', to acquaint the London public with contemporary French art. It was treated with all the derision and incomprehension that would greet the Turner Prize later in the century.

Poster for 'Manet and the Post-Impressionists' exhibition, Grafton Gallery, London, 1910

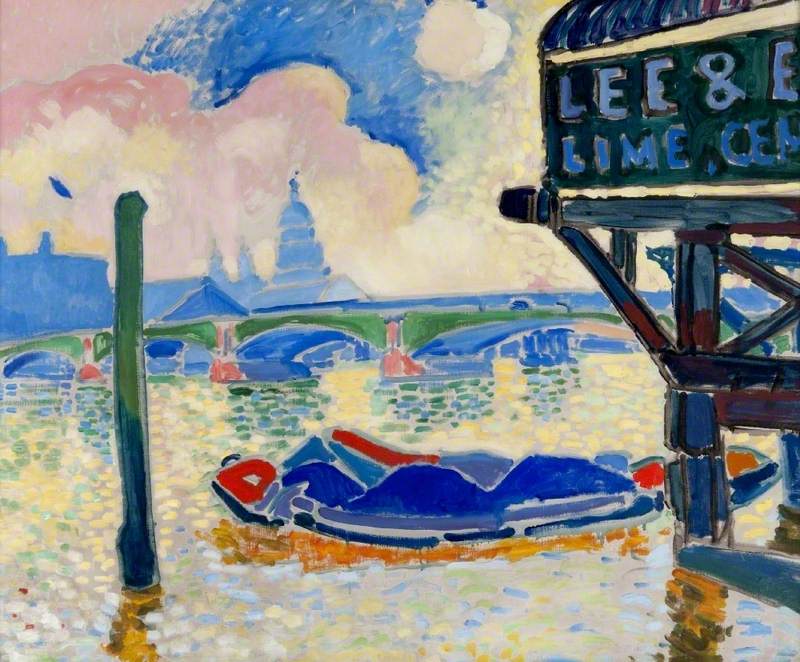

Across the Channel, painting had been moving in experimental new directions for decades. Artists including Paul Cézanne, Paul Gauguin, Georges Seurat and Vincent van Gogh had long since introduced the use of bold colours and simplified or disrupted forms, and now Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Maurice de Vlaminck, André Derain and many others were painting in ways that radically broke from traditional expectations of what might be considered 'art'. But while Paris was a hotbed for artistic modernism, Edwardian London remained resistant to change.

At the supposedly forward-looking New English Art Club, the dominant style was a grandiose but sentimental form of Impressionism, a movement that was now at least 40 years old. Meanwhile, at the Royal Academy, the preference was for society portraits and narrative 'problem pictures' – representational images which reflected the values and lifestyles of the privileged and the wealthy. Clothes were fashionable, backgrounds were plush, sitters were stylish or distinguished.

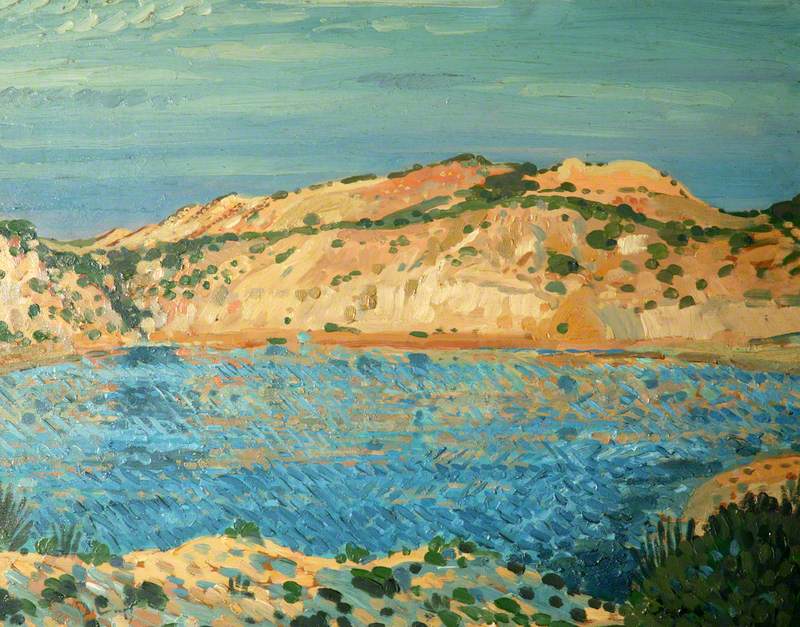

The problem, according to artist Walter Richard Sickert, was that serious art could not flourish within these conditions. Continental in his outlook – he spent many summers in the French port of Dieppe, living there from 1898–1905 and often painting the town and its surrounds – Sickert was an outspoken critic of the English predilection for things that were 'nice'. 'Taste' he argued, 'is the death of a painter.'

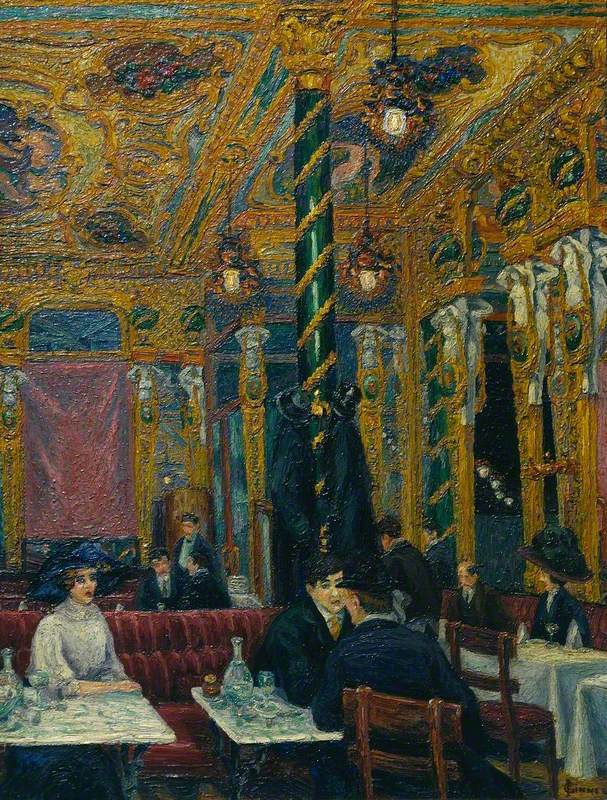

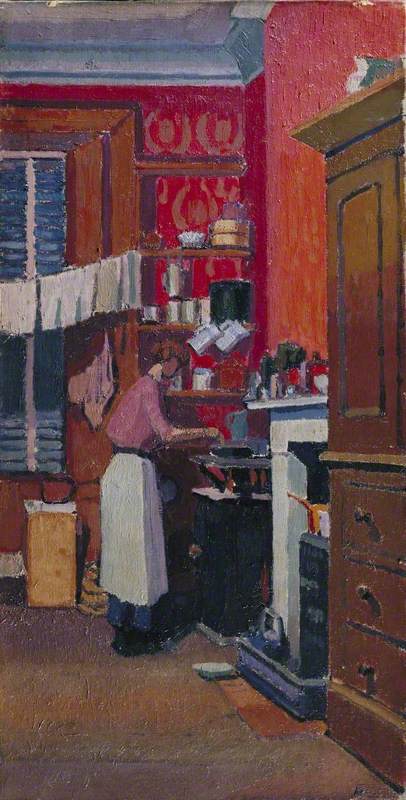

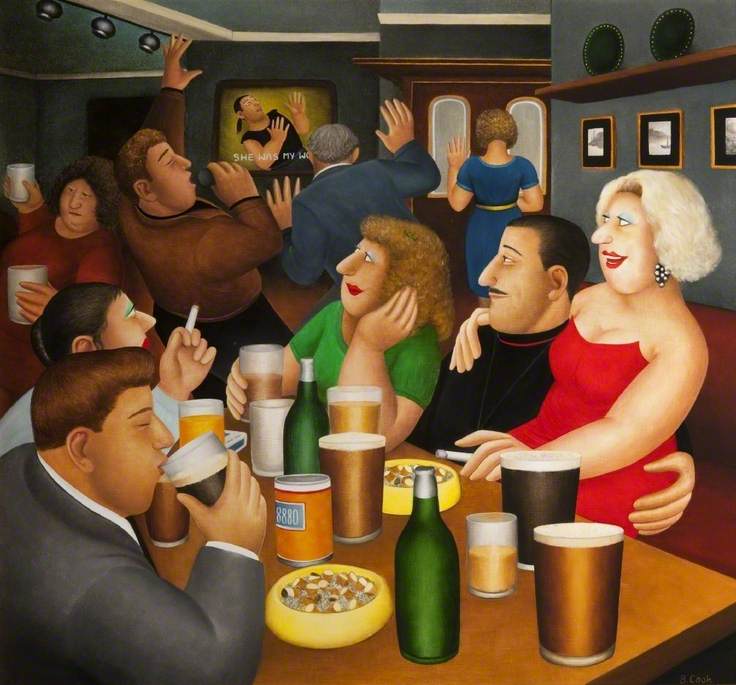

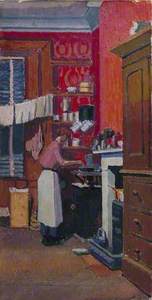

The only use for the drawing room was to caricature it. Instead, he urged artists to 'avoid the drawing-room and stick to the kitchen', tackling subjects that were difficult, dreary, robust and real. He stuck to these beliefs within his own work, producing paintings that were unsentimental, unsettling or unexpected. Some of his best-known pictures were those of Parisian and London music-hall interiors. Disorientating views from odd angles, they feature tawdry details, garishly picked out with his trademark painterly brushstrokes.

Gallery Box at the New Bedford Music Hall, London

1906–1907

Walter Richard Sickert (1860–1942)

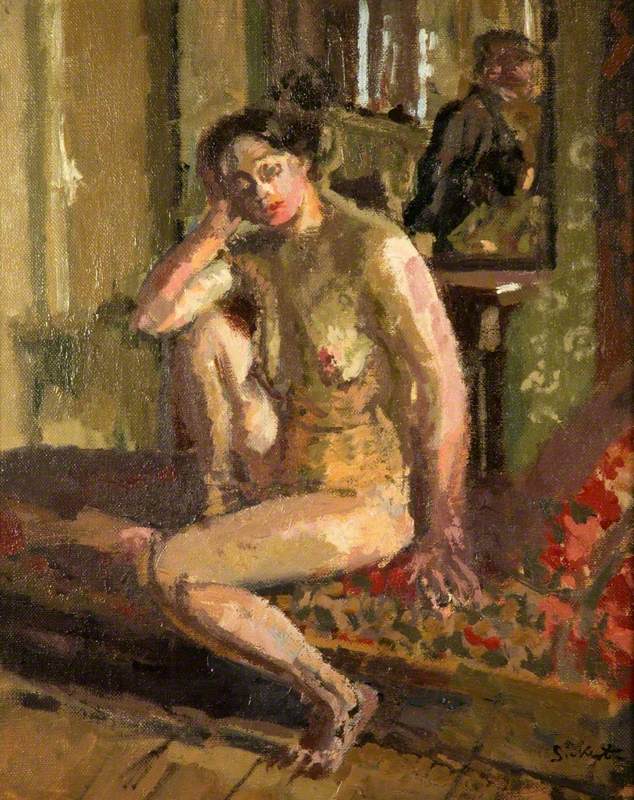

Sickert also painted nudes, bringing an uncompromising realism to his treatment of the naked body. His women have fleshy, imperfect bodies and lie on rumpled bedsheets in dingy bedrooms. The jarring antithesis of elegant drawing rooms or the sentimentalisation of poverty, they would have seemed a world away from the nubile, idealised models of high Victorian and Edwardian art.

In 1911, Sickert became one of the main instigators of a new society designed to shake up the staid complacency of the London art world. Evolving from an earlier artists' collective known as the Fitzroy Street Group, an association was formed to provide an exhibiting platform for self-proclaimed modern artists. United only by the alternative character of their works, the 16 chosen members came together under the prosaically urban title of the Camden Town Group. They held only three exhibitions in 1911 and 1912, but their legacy continued up to and beyond the First World War.

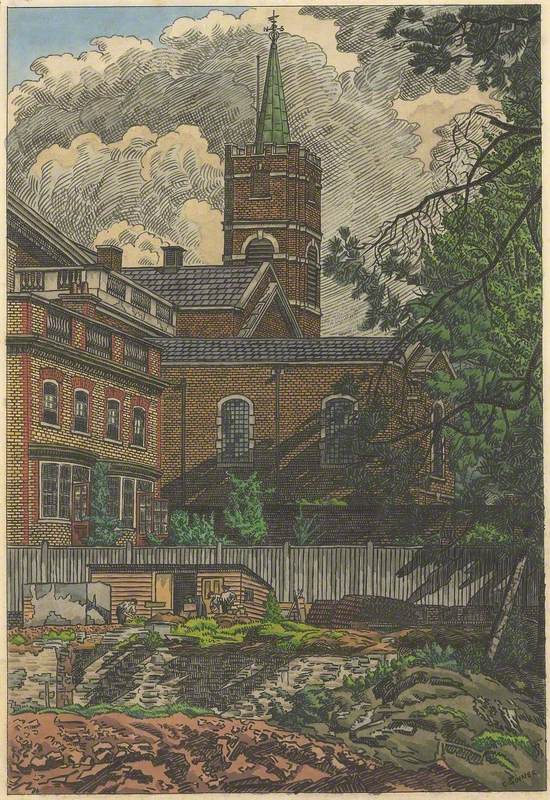

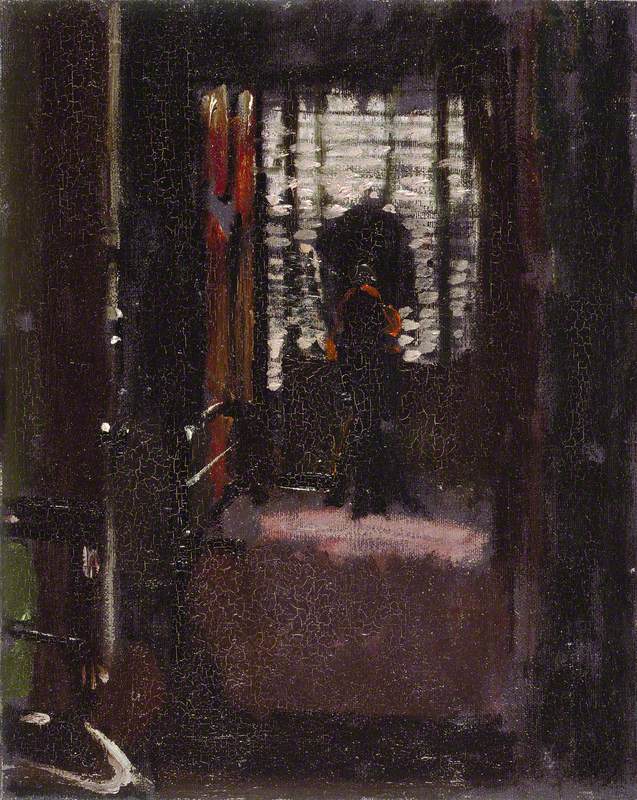

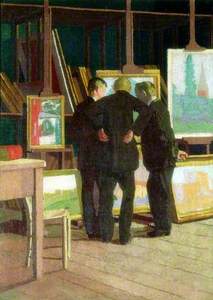

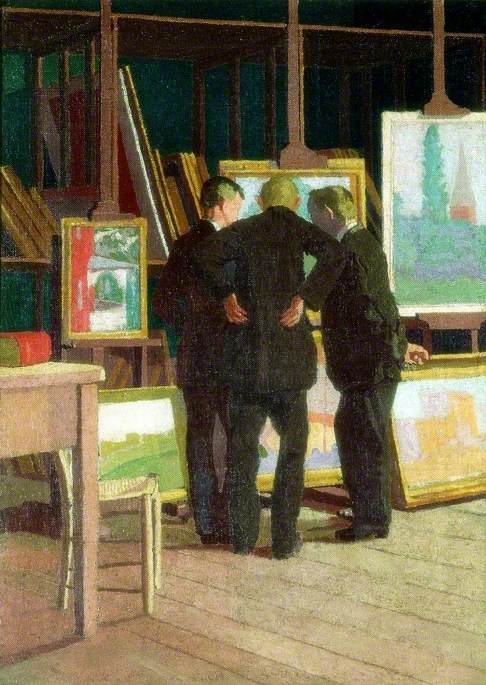

19, Fitzroy Street (Walter Richard Sickert's studio)

1912–1914

Malcolm Drummond (1880–1945)

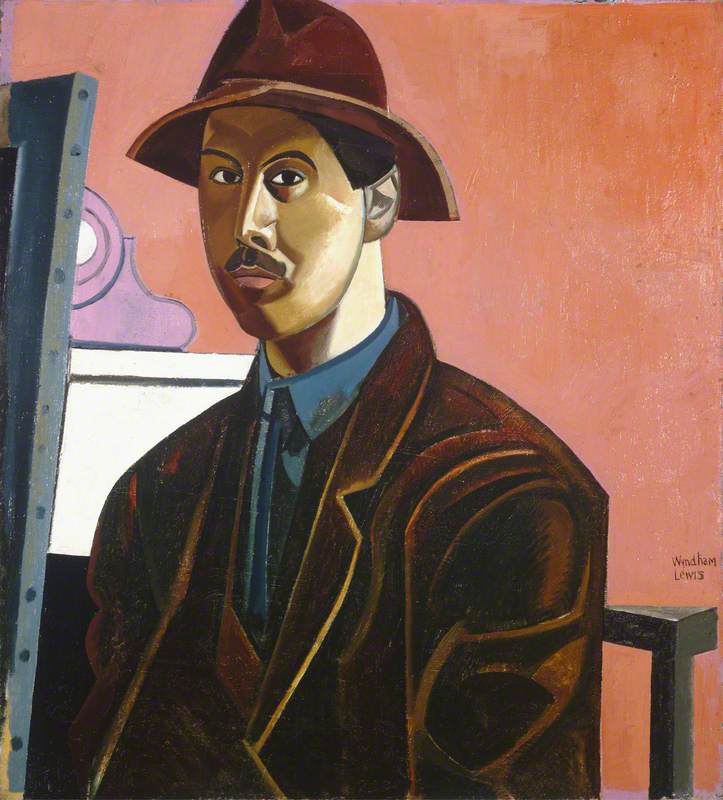

On paper, its aims were broad-minded. Nominally it included artists of widely differing approaches: the bohemian rebel, Augustus John; second-generation Impressionist, Lucien Pissarro; and Wyndham Lewis, an aggressive personality who later founded the cubist offshoot, the Vorticists. Even Bloomsburyite, Duncan Grant joined at one point. The core allies, however, principally considered themselves disciples of Gauguin and Van Gogh.

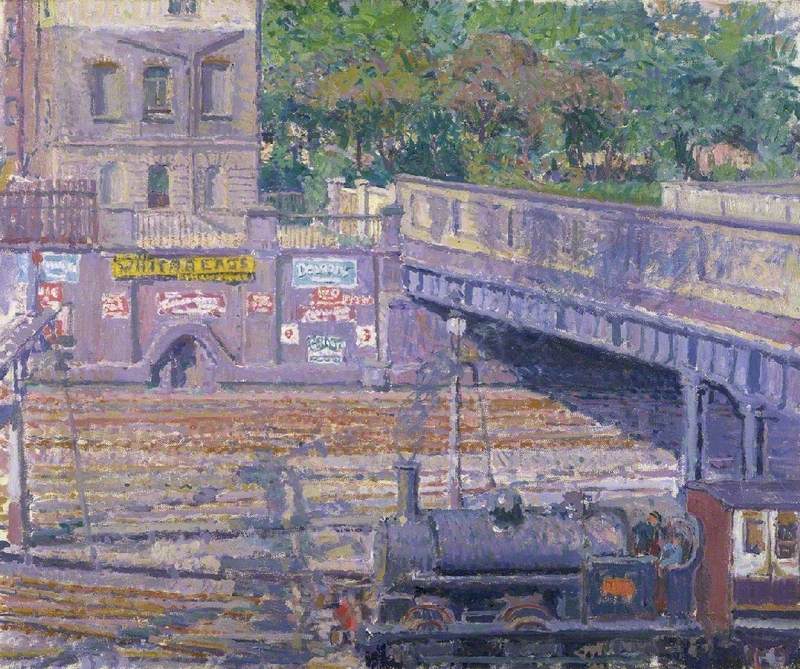

Alongside Sickert (who always remained to some extent apart), the most talented main members were Robert Bevan, Malcolm Drummond, and the three 'Gs' – Harold Gilman, Charles Ginner and Spencer Gore. These men shared a similar visual language. Together they pursued a style of painting characterised by thickly applied paint, bright, flat colours and stylised forms and outlines.

When applied to Sickert's ethos concerning the realist depiction of modern life, these artists forged an identifiable 'Camden Town' style – the nearest thing Britain was to have to home-grown Post-Impressionism.

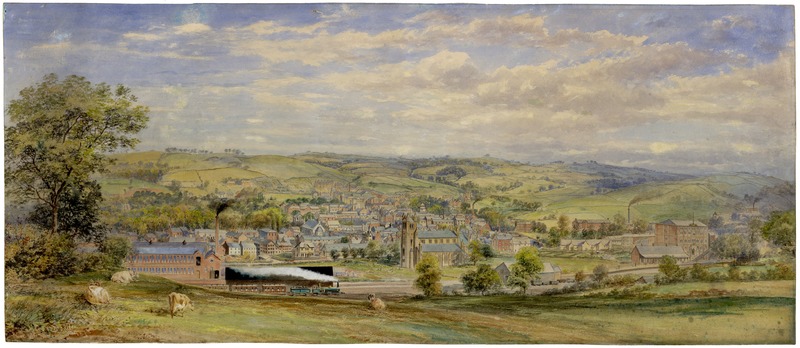

Why 'Camden Town'? Many of the members lived in or around the north-west London neighbourhood but the name was not simply born from geographic coincidence. In truth,

Indeed, the main thing this part of London was famous for during these years was murder. In 1907, a young woman called Emily Dimmock had been brutally killed in her Camden Town bedsitter. The terrible event bestowed upon the area the sort of gruesome associations previously only given to Jack the Ripper's Whitechapel. By adopting a name that inevitably recalled a gratuitous tabloid narrative of violence and prostitution, the Camden Town Group intended to provoke middle-class anxieties about the modern urban experience.

The Camden Town Murder

(also known as ‘What Shall We Do for the Rent?’) c.1908

Walter Richard Sickert (1860–1942)

Sickert painted a sequence of pictures entitled the 'Camden Town Murder' series. Typically featuring the juxtaposition of a clothed man sitting or standing next to a naked woman, these works are menacingly suggestive, without definitively illustrating the event. They play into prejudices concerning the lives of the less well-off. 'The worst kind of slum art' screamed the newspapers when the pictures went to exhibition. But Sickert's paintings are a clever trap. Looking at his ambiguously posed figures there is no visual evidence to confirm a tale of domestic violence or misogyny. If the viewer draws those conclusions they find themself guilty of reading more into the situation than is mischievously implied.

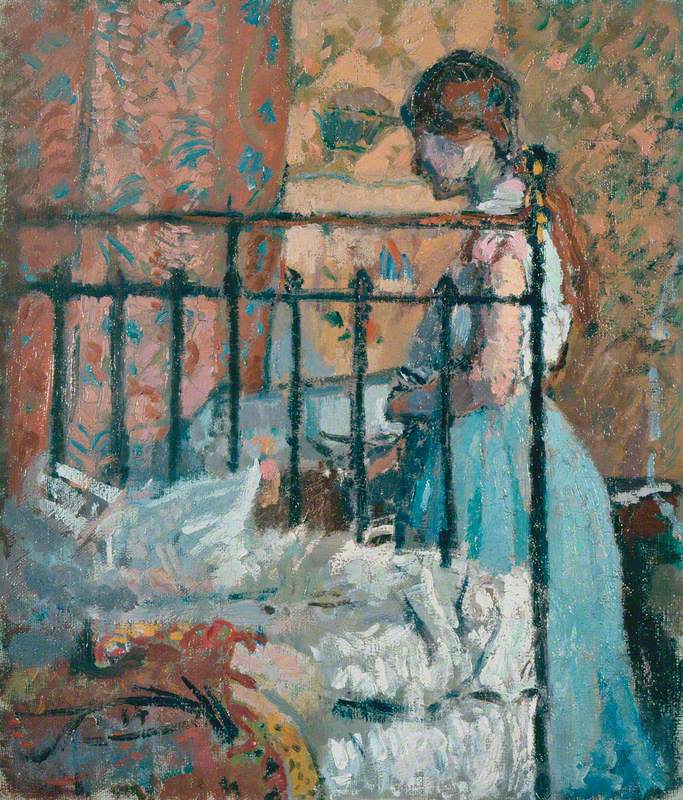

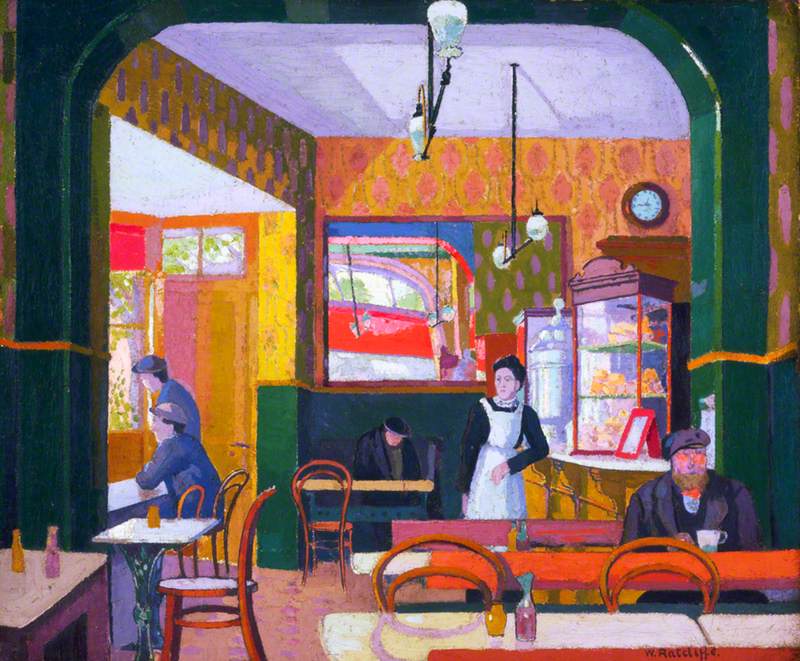

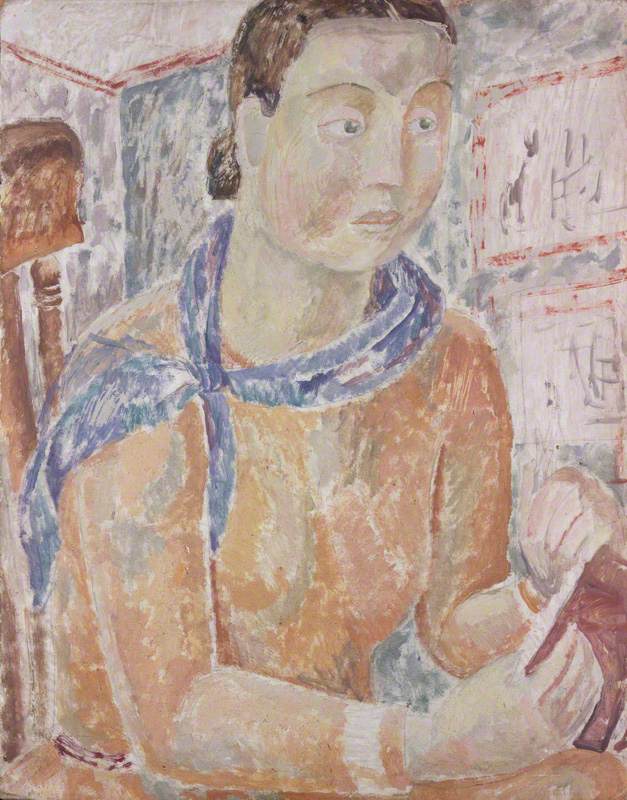

Following Sickert's example, the Camden Town Group set themselves up as challengers to mainstream Edwardian taste. One of the ways they did this was by normalising the modern treatment of everyday things. Typical Camden Town subjects are those which reflect the lived experiences of ordinary men and women. Especially women, in fact. This was the era of the 'New Woman' – a time when the female populace were campaigning for universal suffrage and striving for professional opportunities. Camden Town artists held a mirror up to society and made visible the lives of a class of women not usually considered inspirational material for art.

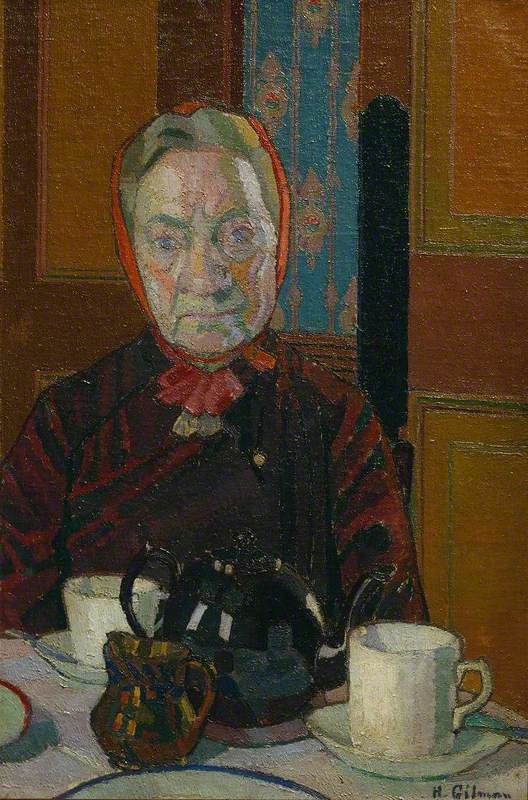

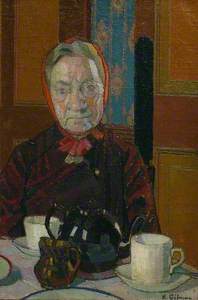

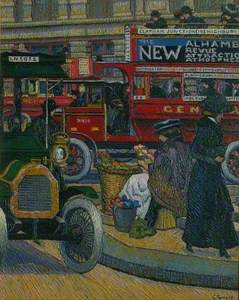

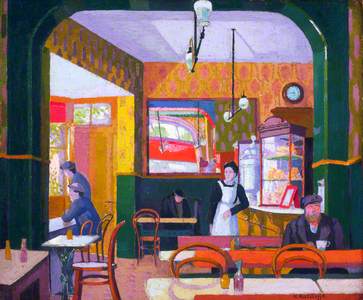

Whether at home, or out in the world of work or leisure, so many Camden Town pictures feature working- or lower-middle-class women in some urban capacity or other. Figures both young and old are seen in the traditionally domestic interiors of the kitchen, the sitting room or the bedroom, but they are also depicted in public spaces – in cafes, music halls, restaurants and parks. There are coster-girls, charwomen and factory workers, wives, mothers, nannies and maids. Gilman portrayed his landlady, Sickert his cleaner. Gore painted women within the theatre, both on and off the stage. Charles Ginner captured the bustling social cross-section of the London streets – a smartly dressed lady walking past a flower seller in Piccadilly Circus.

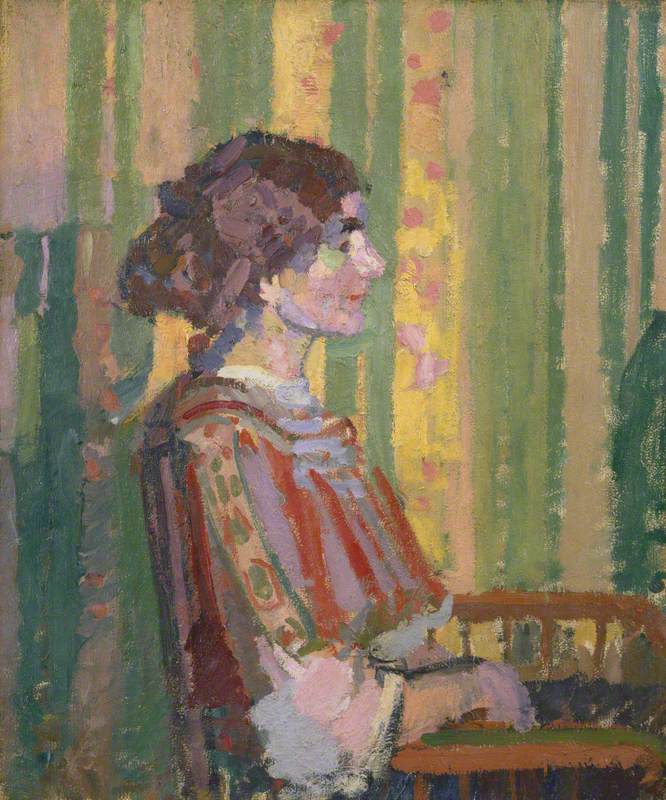

Often there is a detached quality to these pictures, devoid of moral judgement or sexual suggestiveness, even within the nudes. Skin is a decorative patchwork of colour, not more or less important than the patterning of the wallpaper. Femininity might be found within the curve of a back or the tilt of a head but it is by-the-by compared to the painterly textures of the brushstrokes, or the highly-keyed interpretation of light and shadow. This even-handed approach means that the women look comfortably at one with their surroundings.

Camden Town liberality fell short, however, when it came to women participating within the exhibitions. Female artists were not permitted to join. The reason given was that 'amateur' wives and girlfriends 'might not quite come up to the standard aimed at by the group'. It was a ridiculous stipulation. At least two of the male associates were essentially amateurs: William Ratcliffe, a friend of Gilman, and John Doman Turner, a stockbroker's clerk who had taken a correspondence course in art with Gore.

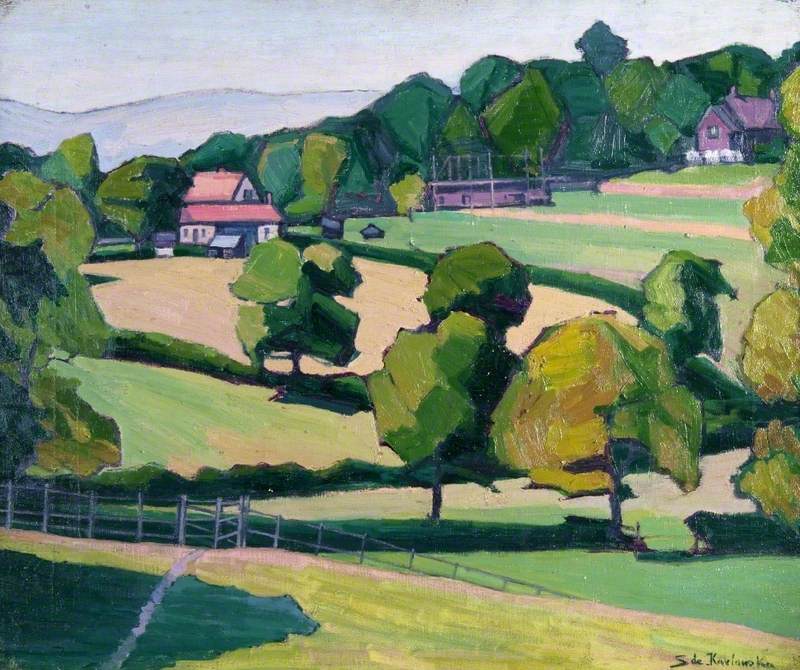

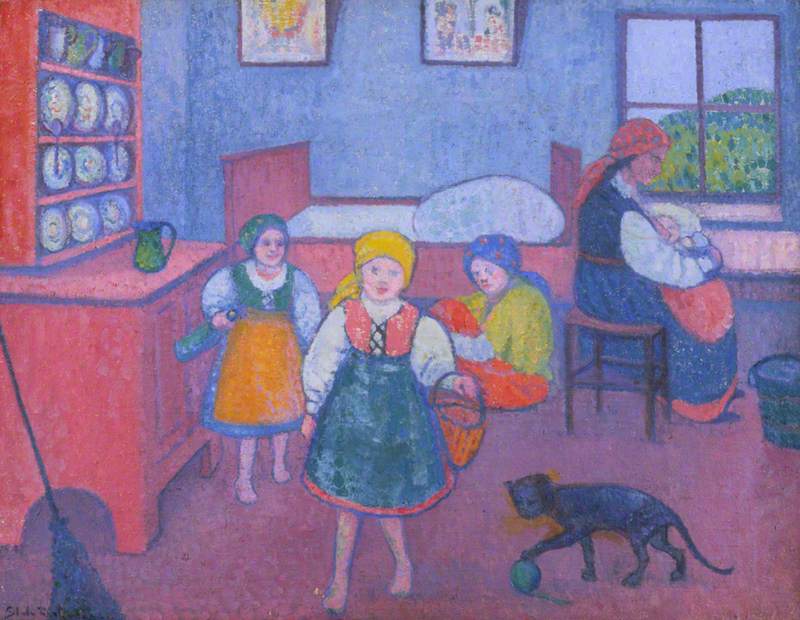

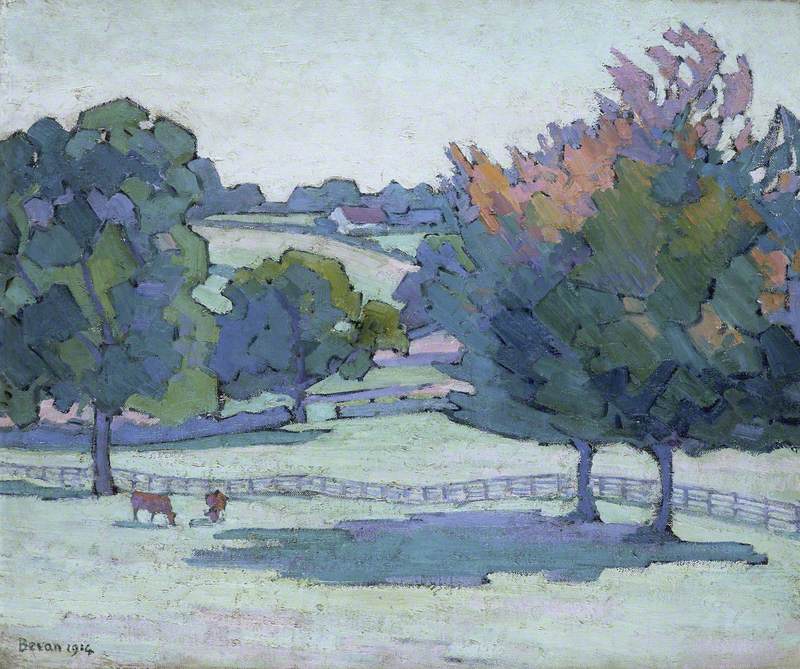

Furthermore, if it was difficult to make ends meet as a British modernist, as a woman it was all but impossible to even become an artist unless you had money in the first place. Few women during this period managed to pursue painting unless they were economically independent or financially supported by male family members. Artist Stanislawa de Karlowska may not have been the main breadwinner for her household but this did not make her paintings less relevant to the Camden Town ethos than those of her husband, Robert Bevan.

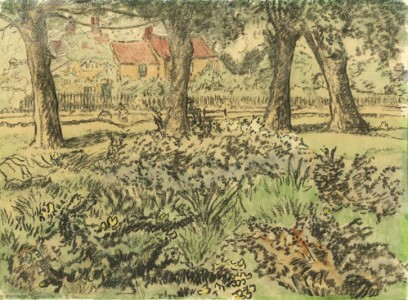

Maples at Cuckfield, Sussex

1914

Robert Polhill Bevan (1865–1925)

So, even as the Camden Towners pulled back the curtain to reveal the lived experience of women, they simultaneously held the door closed against them as professional equals. This blocked a valuable exhibiting opportunity for many talented painters. Had the men-only rule not been put in place the Camden Town Group might have included modern practitioners such as Gwen John, Vanessa Bell, Jessica Dismorr or Helen Saunders. More to the point, it definitely should have included artists who shared elements of the Camden Town vision: De Karlowska, Sylvia Gosse, Nan Hudson, Ethel Sands and others.

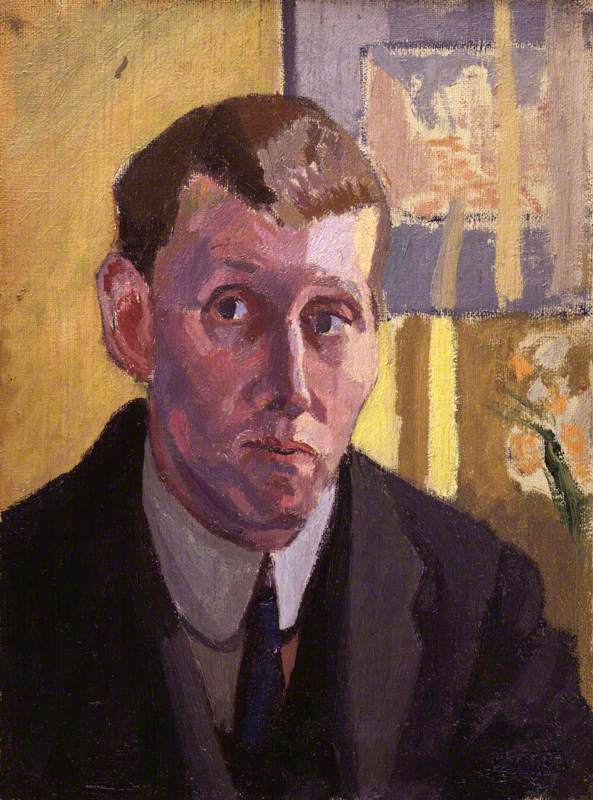

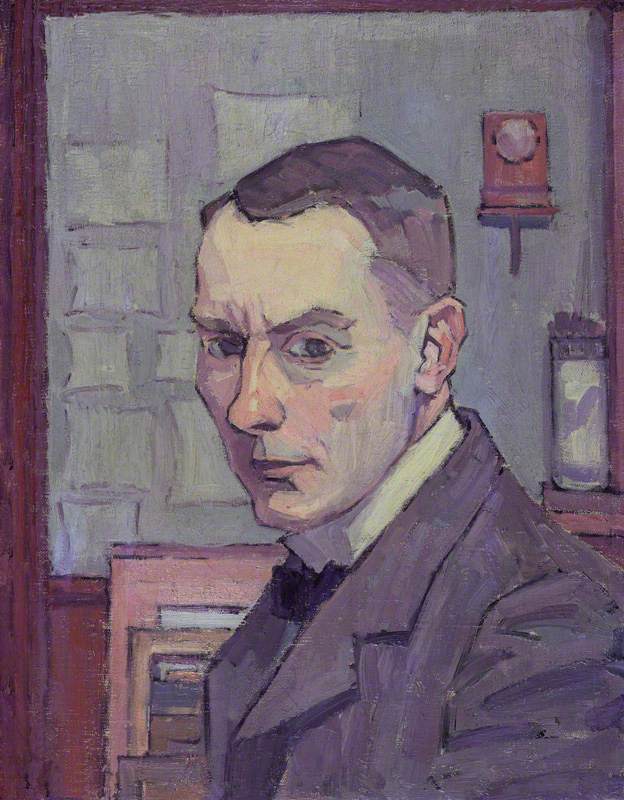

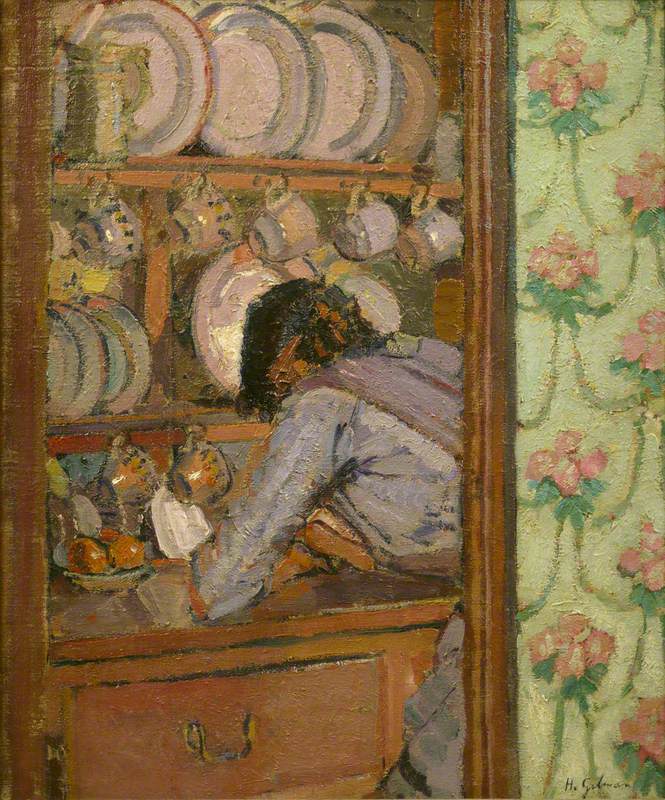

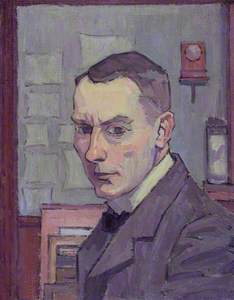

Stanislawa de Karlowska (Mrs Robert Bevan)

c.1913

Harold Gilman (1876–1919)

Despite the short-lived, and short-sighted, nature of their association, the Camden Town Group did succeed in helping pave the way towards an acceptance of modernism. But the exclusion of women was not sustainable – 'not only invidious but impossible!' wrote Sickert to his friend, Nan Hudson. As the language of Post-Impressionism was eclipsed by other, more radical art forms, works by the Camden Town painters quickly began to look dated, like nostalgic period pieces from a bygone age.

To survive they had to adapt. For their last hurrah in 1913, an exhibition held in Brighton embraced a greater depth and breadth of participants, including eight women such as Gosse, Sands, De Karlowska, Thérèse Lessore and Ruth Doggett.

From here the Camden Town Group relaunched itself as the 'London Group', an inclusive organisation for artists of all modern methods which is still in existence today.

Nicola Moorby, art historian and curator

This content was supported by Jerwood Foundation