In seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Europe, Black children trafficked from the African continent were used in visual art as a prop to highlight both the wealth and whiteness of their European enslavers. A regular feature of this Black child adornment was to add an expensive pearl earring to their decoration. The enslaved child was not seen as a person, but as property that signified the wealth of the people or family who commissioned the portrait performance.

The Black child and the pearl were equal parts of an inventory of commodities owned by the family, and as such, they signify the precarious status of the Black child who, like any belonging, can be bought and sold at the will of their owner. The children were sold alongside other chattel, as possessions belonging to their owners.

Daily Post, 26th May 1725, p.1

A beautiful Negro Boy about eight Years of Age, lately come from Barbadoes [sic], to be dispos'd off [sic], any Person that pleases may see the Boy at Mrs Eades, at the Cabinet on Ludgate Hill near Fleet Bridge; who likewise sells Right Barbadoes [sic] Citron Water, and true French Hungary Water.

Pearls and other gems were sourced as an integral part of European imperial operations in fisheries around the world; the seventeenth century saw pearl excavations in places like the Persian Gulf, Bahrain, Venezuela, Panama, and Mexico. In the eighteenth century, when the demand for these gems outgrew the supplies, other locations such as the Gulf of Mannar – controlled by 138 years of Dutch colonisation – were explored and mined for gems. Pearls are viewed as both simple and valuable, especially in great quantities.

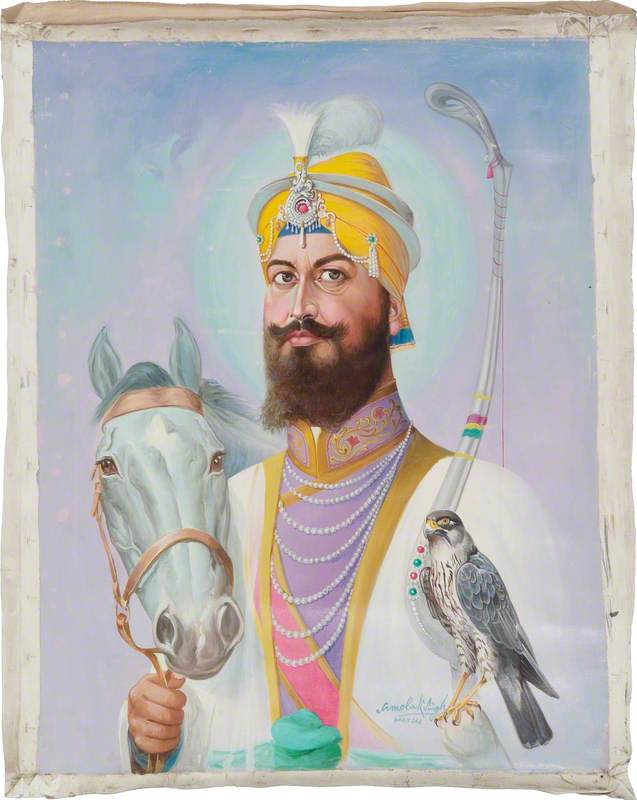

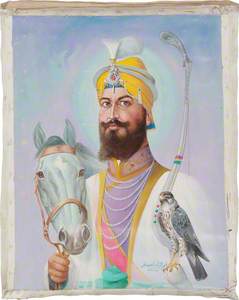

Religious organisations have also used pearls as a symbol of status, as shown in the image of the tenth and final human Sikh Guru, Guru Gobind Singh, who very likely obtained his pearls from the pearl fishery coast in the Gulf of Mannar.

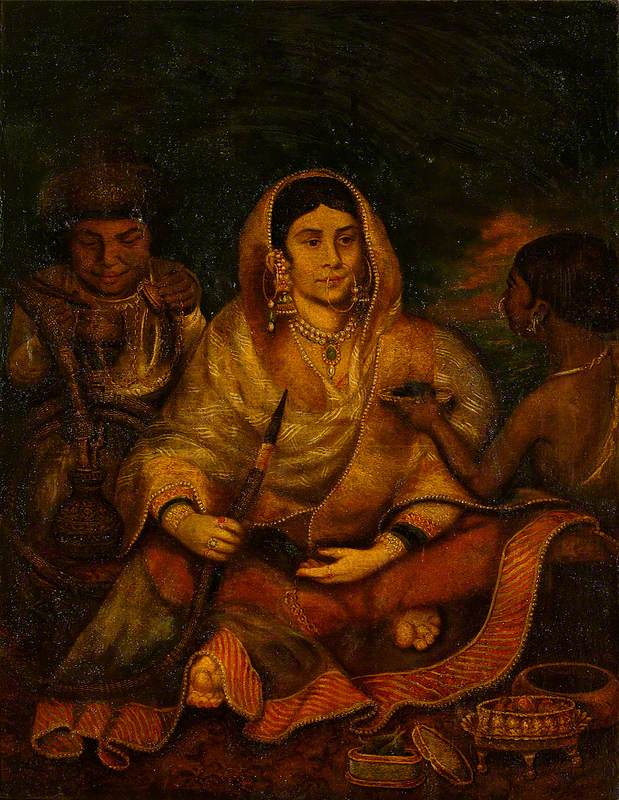

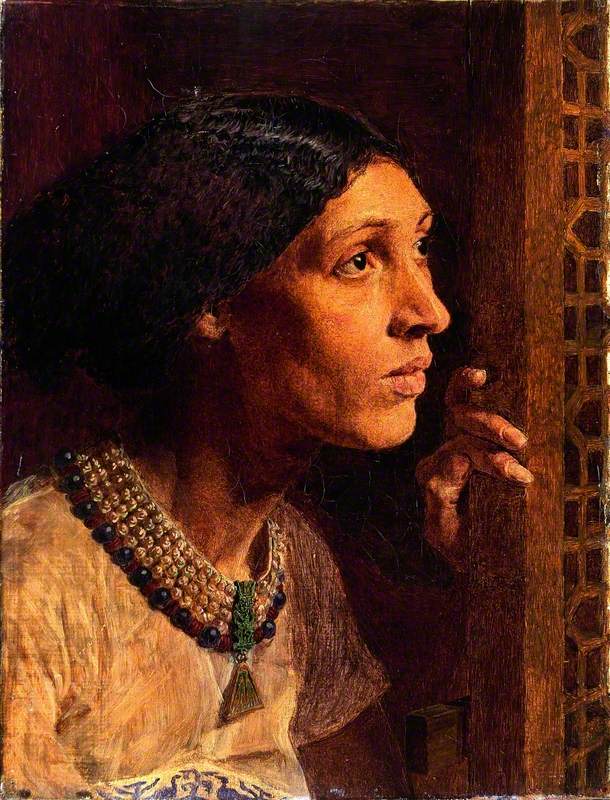

Prince Azim-ud-Daula (1775–1819), Nawab of the Carnatic

Thomas Hickey (1741–1824)

Pearls have traditionally adorned the crowns and thrones of many Persian and Indian emperors and princes, because they were viewed as rare and beautiful – this increased their desirability and value.

Pearls were symbols of bountiful wealth and were often accompanied by other images that depicted excess. As seen in Still Life with Figures, plentiful amounts of fruit, and foods of all varieties, are seen as signifiers of devotion. This scene is overlooked by a smiling Black man wearing a rare red pearl.

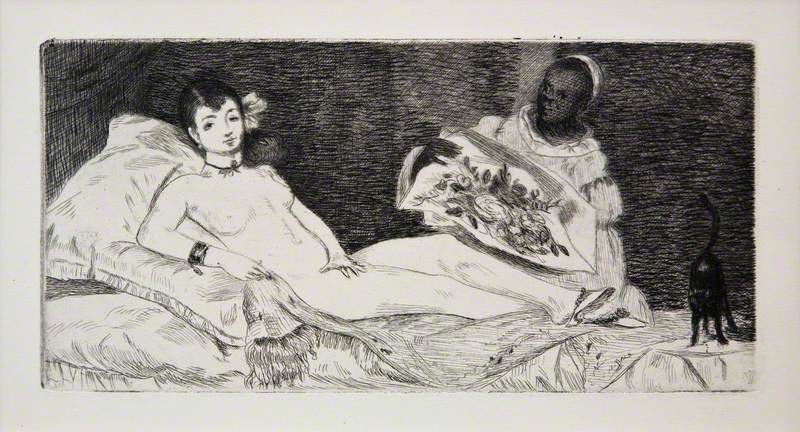

Black individuals wearing pearl earrings are a pictorial trope in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century European art. The juxtaposition of the creamy white pearls with Black skin is an allegory of empire and colonialism. The contrast of the light, white objects and dark-skinned people draw the viewers' eye towards the central image of European whiteness, and apparent cultural refinement; pearls are associated with power, luxury, elegance and wealth.

The composition of these paintings is usually in luxurious surroundings, with the Black individuals dressed in fine clothing in keeping with their household settings. The fruit platters are commodities, like the Black individual, that are significant of high social status and world travel.

Ann De Lisle De Beauvoir (b.1631/1632)

1669

Henri Gascar (1634–1701) (circle of)

The Henri Gascars 1669 painting of Anne De Lisle includes a morose looking Black boy, wearing a collar that may signify enslavement. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, wealthy women were commonly given Black children as slaves to be treated as exotic pets, and were sometimes even sold with pets.

Liverpool General Advertiser, or the Commercial Register, 15th October 1779, p.3

To be Sold by Auction,

At George Dunbar's office, on Thursday next, the 21st instant, at one o'clock,

A Black BOY about 14 years old, and a large Mountain Tyger CAT.

Edinburgh Evening Courant, 18th April 1768, p.3

A BLACK BOY to sell.

TO be sold a BLACK BOY, with long hair, stout made, and well limb'd, is good tempered, can dress hair and take care of a horse indifferently. He has been in Britain near three years.

Any person that inclines to purchase him, may have him for 40 1. He belongs to Captain Abercrombie at Broughton.

This advertisement not to be repeated.

The Black enslaved children were of all ages. Some, sold on to other people after their current owners tired of them, were as young as five or six years old.

Daily Advertiser, 15th March 1742, p.3

To be SOLD, THE Time of a little Black Boy, between five and six Years old, and bound till of Age, a pretty sharp Child, and speaks nothing but English. Any Person minded to purchase him, may be further inform'd by the Owner, next Door to the Salutation Tavern in Cowley-Street, Westminster.

Those Black boys with a position in a wealthy household did, for a period of time, experience a life of a different standard to that of the plantations from where they were taken, and sometimes returned. This included dressing in pearls and fine clothing that reflected the status of their owners.

The wearing of a pearl earring signifies a relationship with someone of considerable wealth and resources. This connection signifies an imbalance of power because of the rarity of pearls and the social position of the wearer – an enslaved boy. Pearls were generally only worn by white women or enslaved Black boys, thus imbuing the wearer with a gender ambiguity in the European world. As a Black child, the individual is de-gendered and not seen as either male or female, but as an entity that has neither the cultural attributes of the feminine nor the masculine status.

In art, and society, there is a pluralistic meaning to pearls depending upon whose body they appear. A European white women's status is indicated by the setting, their hair, and their style of dress: it is this combination of factors that determines how the wearer of the pearls is viewed. Towards the end of the seventeenth century, a single earring or a single strand of pearls on a white woman was thought to connect the wearer to sexual deviancy, unless linked to other visual and literary iconography of heaven. Meanwhile, multiple strands of pearls serve to flatter the complexion and act as symbols of both wealth and faith – a strong connection to God: these white European women were viewed as chaste, feminine, and almost holy.

Mary Helden (1726–1766) with a Dog and Her Black Page, 'Sambo'

1739

Charles Philips (1708–1747)

The Black person featured in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century art was frequently referred to as a Moor, a Sambo, a blackamoor, or a slave – all terms that obscured their individual cultural heritage, and personality. Additionally, from the Eurocentric point of view of the commissioned artist, the featured aristocrat and the viewers of this art, there is the contrast of the simplistic beauty of the pearl gem with the perceived beauty – or lack thereof – of the wearer. There is a possibility that the addition of the pearl earring was supposed to enhance the visage of the enslaved child to make them more appealing to the observer.

If pearls were not available to highlight the wealth of European enslavers, then a gold or silver collar was often worn.

The collar can be read as a symbol of belonging to another human being, a token of enslavement. Sometimes a metal collar and pearl were combined, as in this 1725 portrait of A Young Girl with an Enslaved Servant and a Dog.

A Young Girl with an Enslaved Servant and a Dog

c.1725

Bartholomew Dandridge (1691–c.1754)

In the 1708 portrait by Philip Vilain, entitled Girl with a Dog, the Black boy, like the dog, is also wearing a collar, but he is not mentioned, and is painted in colours that blend him into the background. This was a standard practice that rendered the Black presence in British society almost invisible while still discreetly noting it.

Most enslaved children portrayed with pearl decorations were boys. A rare example in European art of a Black girl wearing a string of pearls with her enslaver is shown in Pierre Mignard I's portrait of Louise de Kéroualle, Duchess of Portsmouth.

Louise de Kéroualle, Duchess of Portsmouth

1682

Pierre Mignard I (1612–1695)

In a strange reversal, the Duchess is shown with a single large pearl earring in her ear, and one on her dress, while the well-dressed enslaved girl has a complete string of pearls around her neck, and holds coral with a conch full of pearls. The Black girl's colour serves to illuminate the almost alabaster skin colour that is used to depict the complexion of the Duchess of Portsmouth.

The dress that the Duchess is wearing is also decorated with colourful collections of gems on the sleeve and the bodice which suggests wealth, resources and global travel. The riches of European empires are depicted on both the body of the enslaved person and the gems liberally displayed as accessories in the setting of the commissioned paintings.

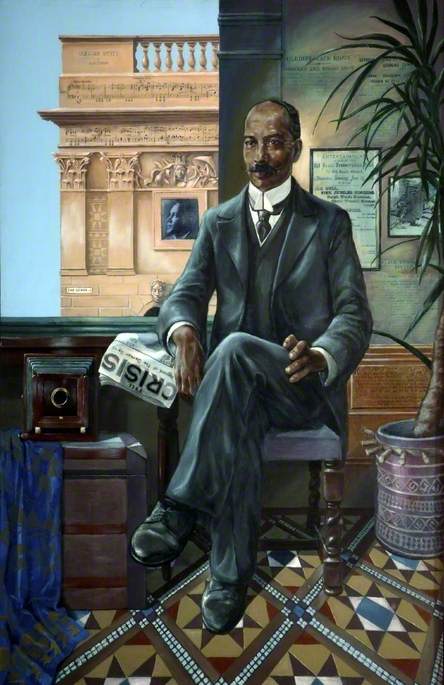

The early capitalist benefactors of empire were proud to show the source and the result of their wealth. By using Black bodies in their portraits, capitalists indicated how their wealth was gained and publicly acknowledged themselves as the beneficiaries of this trade in human beings.

The artistic trope of the 'boy with the pearl earring' is the epitome of how the upper classes in European society decorated and displayed their forays into human trafficking and continued global exploitation in the name of empire.

Marjorie H. Morgan, playwright, director, producer and journalist