Historically speaking, the art collector has embodied grandiose wealth, connoisseurship and (debatable) taste. Artworks of collectors tend to represent them as aspirational and distinguished individuals, as they show them off to friends and admirers who studiously contemplate the collection.

Interior of a Picture Gallery with the Collection of Cardinal Silvio Valenti Gonzaga

1749, oil on canvas by Giovanni Paolo Panini (c.1691–c.1765)

Although these collectors belong to the past, we have them to thank, in part, for public collections across the UK today.

Notable examples are the collections of John Julius Angerstein, which later formed part of The National Gallery, and Sir Richard Wallace whose collection now exists as The Wallace Collection.

Stop and consider though – if we consciously replace the term 'collector' with 'art hoarder', our readings change dramatically. The NHS definition of hoarding describes the 'unorganised' and 'excessive' amassing of objects that hold emotional or psychological significance. To be a hoarder is to collect pathologically a 'number of items and store them in a chaotic manner, usually resulting in unmanageable amounts of clutter'.

When does the compulsion of an art collector, connoisseur, patron or enthusiast allow them to slip precariously into being an art hoarder? The distinction is subjective but worth weighing up when we consider British art collections.

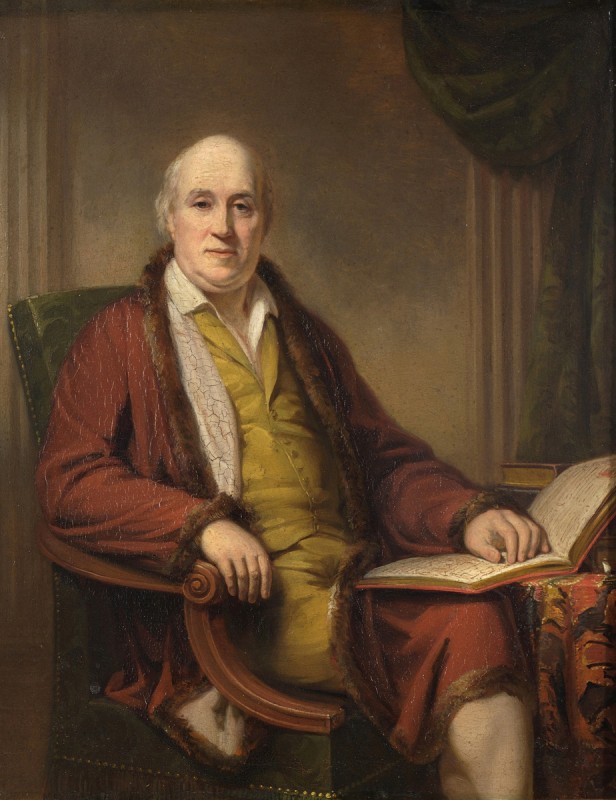

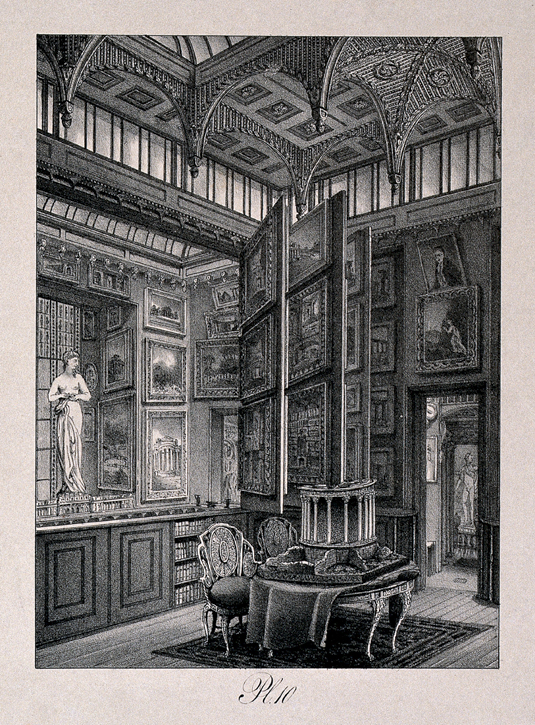

Unlike modern, minimalist art galleries with bare walls, collectors previously packed as much art as possible into one space, in what we might call today 'maximalism'. This manner of displaying art can be positive, as in the case of Sir John Soane, one of the foremost architects of the Regency period (1811–1820) and an avid collector of sculptures, paintings and architectural fragments. In his lifetime he began to transform his home into Sir John Soane's Museum, which now occupies three remodelled houses in Lincoln's Inn Fields in London.

Sir John Soane (1753–1836), RA

(after Sir Thomas Lawrence) 1836

John Wood (1801–1870)

The transition of Soane's home into a museum is truly remarkable. After we enter the traditional front door we are transported into a fantastical interior. World history in the form of art adorns every conceivable surface, and one can end up weaving through the labyrinth of pieces with childlike awe. Despite the intensity, everything is carefully ordered, displayed and arranged in a pleasant geometry.

Confronted with this salon-display-on-steroids, our senses simply cannot soak up the full breadth of what we find before us. In the manner once described by a young architect employed by Soane, we deliberately seek out the 'positive sense of suffocation' in this disorientating maze.

Sir John Soane's House and Museum: the picture gallery at ground floor level

1830, lithograph published by C. Hullmandel

The aesthetic of the congested and cluttered interior informs our perceptions of Victorian Britain. In an age of increasing mass production, homes across the country sought to optimise and amplify the display of their wealth and possessions. Nineteenth-century art portrayed this in tandem, as seen in Rembrandt's Studio by John Scarlett Davis (1804–1845), which reveals a fictional cavernous space packed with masterpieces.

Rembrandt van Rijn is pictured mid-creation, whilst adoring patrons linger nearby. Rembrandt's 'greatest hits', including The Night Watch, are crushed together in a fantasy exhibition that defies time and production date. The image is warm, appealing, domestic even – and reflects Davis' speciality of capturing the interiors of art galleries.

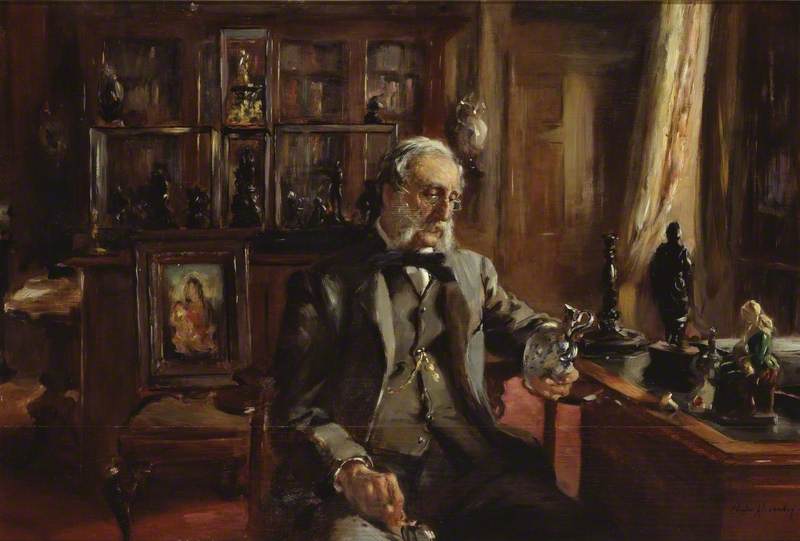

In L'amateur chez lui (The Collector at Home) by Charles Alexander (1864–1915), the artist conjures up an atmosphere of wistful melancholy. Here, the collector sits alone with his collection, in dappled gentle light. He is at once surrounded and yet alone – the artworks are his only companions, through which he retreats into memory.

L'amateur chez lui (The Collector at Home)

exhibited 1893–1894

Charles Alexander (1864–1915)

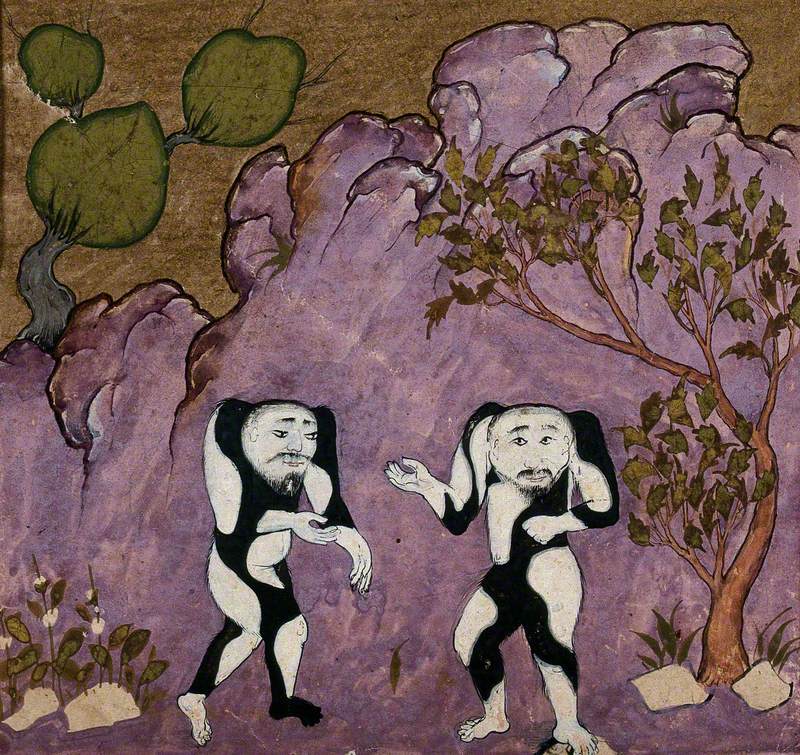

The art 'hoard' and 'cabinets of curiosities' have their roots in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, though collections existed before this. We find a seductively warm warren of art in The Interior of a Picture Gallery by Frans Francken II (1581–1642) and David Teniers II (1610–1690).

The Interior of a Picture Gallery

c.1640

Frans Francken II (1581–1642) and David Teniers II (1610–1690)

Earthy hues and rich fabrics pull us in deeper to envelop us in a scene of capitalist excess, where artworks are piled on top of each other, ready for our exploring eyes and presumably available for purchase. Mentally insert the senses and smell of being in an antique shop for extra contemporary immersion here.

Abundance becomes overwhelming, as seen in the luxurious Cognoscenti in a Room hung with Pictures by the Flemish School.

Exclusively male and almost aggressively large in scale, this cavernous gallery space grants us a fleeting glimpse into an elite world.

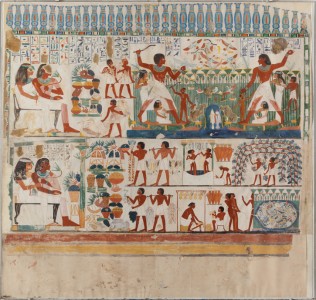

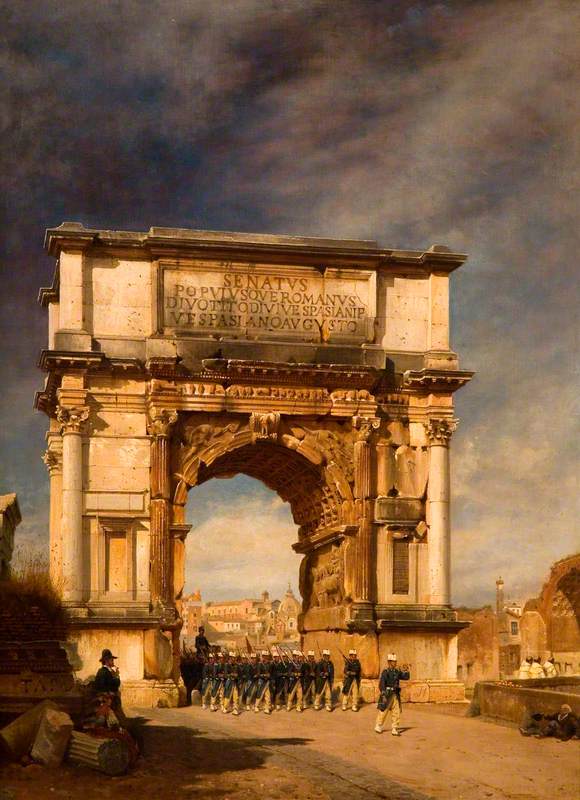

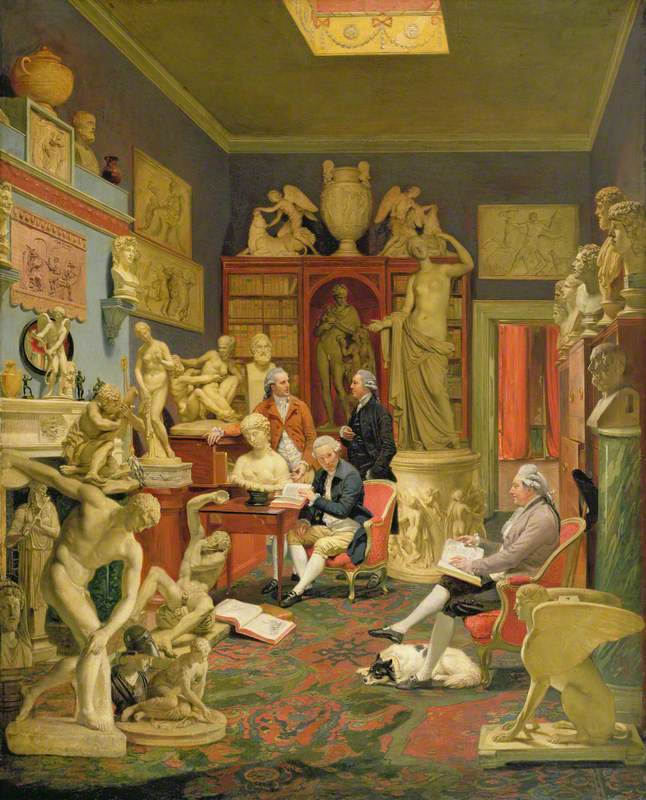

Charles Townley and Friends in His Library at Park Street, Westminster by Johann Zoffany (1733–1810) captures a collection (or is it a hoard?), one which poses a dilemma for contemporary audiences steeped in debate over colonialism.

Charles Townley and Friends in His Library at Park Street, Westminster

1781–1790 & 1798

Johann Zoffany (1733–1810)

Townley was a wealthy Englishman, who, in the course of three Grand Tours, amassed a sizeable collection of antiques. Here, an elegant clutter of antiquity is surveyed by Townley and company – art treasures from across the western world and beyond pack together creating a landscape of acquisition.

Artworks removed from both context and nationality are gathered in a display of British dominance. Some of Townley's collection went on to form part of the British Museum's collection. It seems symptomatic of the eighteenth-century Grand Tour that it wasn't enough simply to see the art of other cultures – one had to acquire and possess it too.

In this instance, the dominance and reach of the British Empire are reflected by the sumptuous hoard, and in that light, the image can be read today as an allegory of an aggressive colonial mindset. Although the Roman Empire itself was not around to be colonised, the political and artistic ideals of Rome were colonised by the British through the acquisition of art.

At what point was one sculpture too many here? It reminds us that not all collections exclusively reflect a love of art, but sometimes a power-grab too.

The Brussels Picture Gallery of the Archduke Leopold Wilhelm of Austria (1614–1662) by David Teniers II is a culmination of excess and, through the lens of hoarding, a deeply troubling piece.

The Brussels Picture Gallery of the Archduke Leopold Wilhelm of Austria (1614–1662)

1651

David Teniers II (1610–1690)

Exclusively male again and aggressive in its size (almost to the point of overcompensation), it's an inherently monarchical and political space packed to the brim with western art. Grand? Yes. Too much? Yes.

The Archduke owned 517 Italian High Renaissance pictures, many of which were acquired from the English royal collection after the execution of Charles I in 1649.

Consider the hygiene implications of this scene – we see a space which is impossible to clean where animals and humans mix. The works are inaccessible individually in a sea of images pushed together as one, merging and jostling together without a break. It's dark, almost murky and shocking in its excess.

If we argue that the act of hoarding possibly shaped many collections in the UK today, it feels appropriate to acknowledge the 'very strong emotional attachment to the objects' once held by those who amassed them. By considering the morality in the acquisition of art, we arguably cannot always discuss these sizeable collections with the same reverence.

What becomes clear is that the motives behind acquiring artworks are as nuanced as the paintings themselves. Whether we view these as positive or negative, they offer, at the very least, a tool to connect with those from the past.

Jon Sleigh, freelance arts educator

.jpg)