The landscapes of Glaswegian artist Carol Rhodes may seem filled with contradictions: familiar, yet alien, flat, yet viewed from great heights. Although she painted on small-sized panels, her works feature vast and expansive landscapes.

When you notice something, really notice it, you're inside it and outside it at the same time.

The artist's recent retrospective 'Carol Rhodes: See the World' at Glasgow International is the first survey of her work since her death in 2018, and invites deep considerations about human intervention in nature. By forcing a close gaze, Rhodes' works encourage us to reconsider familiar landscapes and how we inhabit them.

Born in 1959 in Edinburgh to a detective and a doctor, Rhodes' early life was one filled with changing landscapes. After her birth, her family moved to the city of Serampore in West Bengal, India, where her parents took on roles as missionaries for the Church of Scotland. Aged 14 she was sent to boarding school in the Himalayas; the steam trains she took to school each term, snaking through mountainous terrain, would prove formative to her future artistic observations.

The education at Woodstock School proved liberating to her; a hands-off approach to learning meant that she and her friends were surrounded by a subculture of pacifism (and marijuana consumption) that co-existed with Christian teachings. It was a philosophy that would later appear in her work, which tended to criticise modern society and reflect her personal involvement in anti-war causes throughout her life.

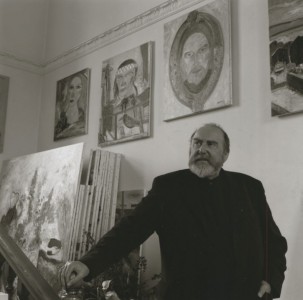

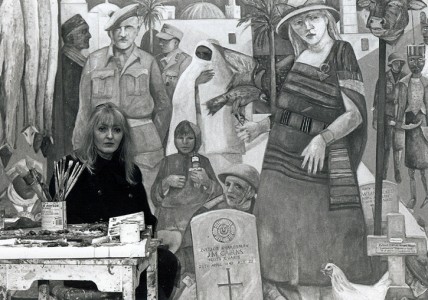

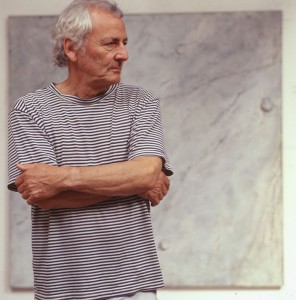

On her return to the UK, she studied at the Glasgow School of Art, where she took classes by the realist painter Alexander (Sandy) Moffatt. Later, she would also teach at the university.

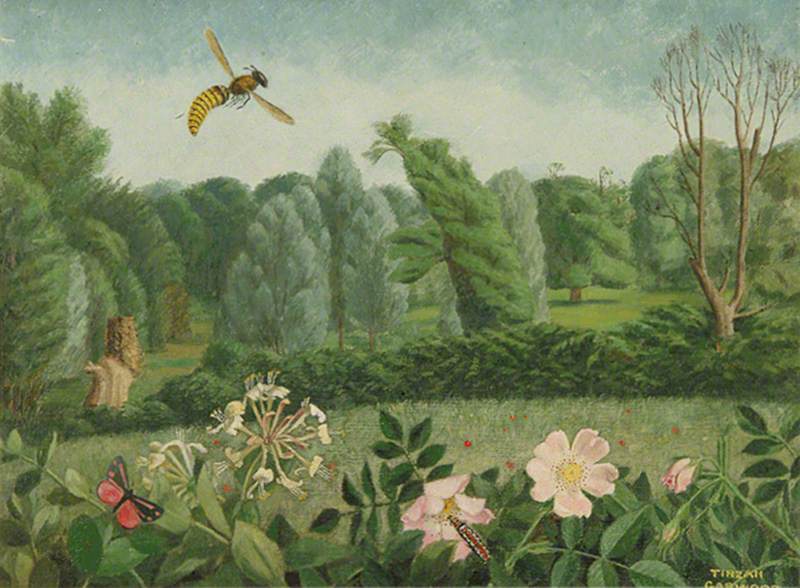

Her early influences included a range of artistic figures, from Walter Sickert to Nicholas Poussin and Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin – artists who shared a keen observation of environments and capturing them with dramatic softness. Rhodes channelled these influences in some of her more verdant depictions of the natural terrain: pastel, light, and fragile, intruded upon by human activity.

Yet, as critic David Cohen writes, she was a realist, 'in the sense of the acuteness of her politics and the unsentimental report of her gaze'. Unlike the unspoiled, scenic undulation of the landscape she witnessed on the train rides she took as a teenager, she chose to paint markedly more human-centred spaces bordering town and country which the land use campaigner Marian Shoard called 'edgelands': rest stops, industrial estates, suburban enclaves encroaching on untouched nature.

Coinciding with her increasing involvement in left-wing activism, notably within feminist and pacifist movements, Rhodes stopped painting soon after her formal artistic training, around the time of the popular resurgence of the New Glasgow Boys style of painting that was characterised by brash male bravado and characters. Instead she opted to work as an administrator and technician for the Tramway and Transmission Galleries in Glasgow, the latter of which she co-founded, and involved herself in the founding of the Glasgow Free University for knowledge and skill sharing.

Returning to painting a decade later, Rhodes was initially a painter of single objects. But her attention quickly shifted towards landscapes with the birth of her son in 1992, having spent many afternoons observing the natural scenes of Scotland around her whilst pushing young Hamish in his buggy. Landscapes were a style and subject matter that stuck – she would focus exclusively on them throughout the rest of her artistic practice.

While some critics have called Rhodes' landscapes moralistic, emphasising the utilitarian nature of the sites she depicts, others downplay the politicisation of the landscapes, insisting on their subtlety. The writer and artist Merlin James, whom Rhodes met and married around the turn of the millennium, described her painting as both celebrating and lamenting 'the anti-idyll of the industrialised world'.

That Rhodes was a tireless campaigner against the presence of nuclear power plants in Scotland – she had once been handcuffed by police at a sit-in protest at the Faslane nuclear submarine base – may lend us a hint as to how she felt about mass human intervention on hitherto untouched lands.

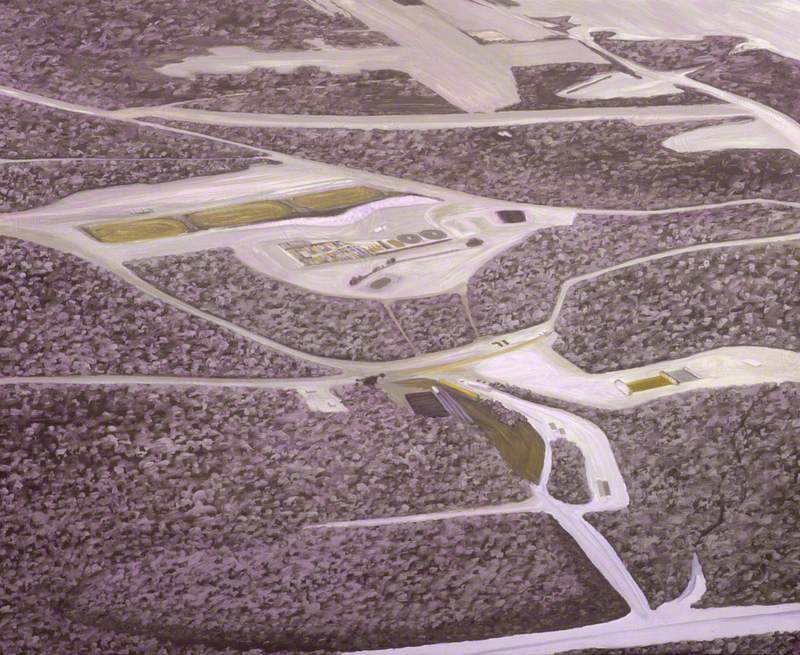

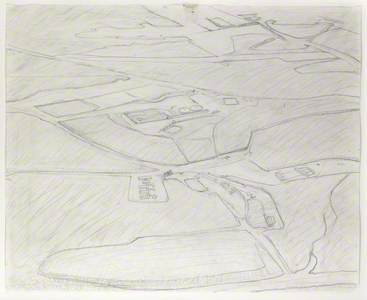

Though she focused on aerial, topographic depictions in her landscapes – having referred heavily to geographical textbooks, planning blueprints, and photographs she took herself from helicopters as source material – Rhodes avoided architectural exactitude, preferring instead to abstractify her work in a way that emphasised absence and disaffection. The result is that scenes look intensely familiar without pointing to anywhere rooted in reality. The critic Tom Lubbock referred to these landscapes as 'lying between fiction and documentary'.

Rhodes depicted sites from a middle distance – between a close-up and an abstracted distance – creating a voyeuristic and surveillant viewing plane. 'Distance needn't mean you're detached,' she said. 'When you notice something, really notice it, you're inside it and outside it at the same time.'

Rhodes plays with scale to present a scene of tension between whether humanity or nature will prevail. Carpark, Canal (1994), one of her earliest forays into landscapes, features an endlessness to the canal's width: the foreground of water asserts itself over a seemingly vast sandiness hugging the edges of the car park.

But in other depictions such as Ridge (1999) and Industrial Landscape (1997) we see human infrastructure, including roads and depots, begin to encroach steadily on previously untouched land from the corners of the canvas. They stretch and snake their way around the canvas the same way flora grows, a reflection of the opportunism of human activity, springing up anywhere it can akin to seedlings.

Often described as 'non-places' – facilities that are part of the infrastructure designed to sink into the background hum of human life – the subjects of Rhodes' paintings churn out intense economic activity that can be quickly transported into larger towns and cities, sites which Moira Jeffrey described as being on 'the periphery of capitalism; the periphery of globalisation.'

For how labour and resource-intensive these sites are, Rhodes' landscapes feature a noticeable absence of people, transport, or indeed movement. Instead they are apocalyptic snapshots of relentless productivity.

Perhaps most telling of the damaging capacity of industrialisation in such sites is the motif of spillages, which feature prominently in Rhodes' works. In Industrial Belt (2006), the products (or perhaps by-products) of industry are rendered as murky, melting swirls of paint, akin to an oil spill. Human activity is vast, occupying a chunk of the panel, the infrastructural elements encroaching on the wild green space of the foreground.

But beyond their status as haunting allegories, Rhodes' landscapes contain a humorous side. When painting she found it funny when large and small features were placed next to each other, or if a path took an unexpected turn. Canal, Hill, Rail (2001) may be most reflective of this, illustrating the separate named features as if they were itemised on a catalogue: canal on the left, the hill on the right, and a railway track making its way into the terrain. But what's that unknown, black blob that seems like a speech bubble rising in the middle?

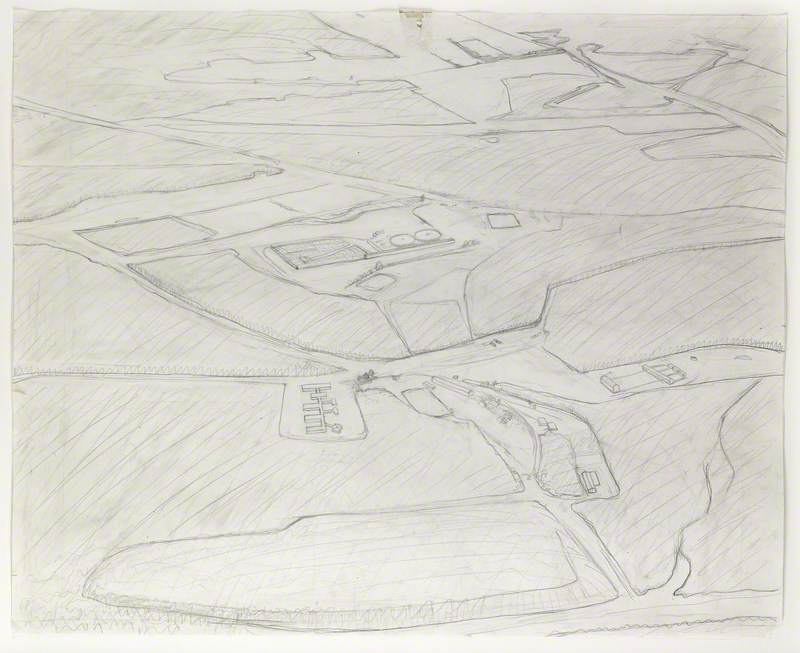

Rhodes took careful and meticulous planning to create the works, including numerous preparatory drawings, as seen in Tree and Works (2001). She was a perfectionist in her craft, repeatedly wiping off areas and repainting them, and discarding entire works if she was at all dissatisfied with the direction they took. Because of these exhaustive processes, she produced only five works a year.

Towards the end of her career, she began to paint more populated, urban centres, such as in Town (2005) and Houses, Gardens (2007). Yet for all their architectural busyness they remain equally, and startlingly, devoid of signs of life.

Diagnosed with motor neurone disease in 2013 after an incessant pain in her knee, Rhodes painted her final works in 2016. By this time she could no longer paint due to the advanced effects of illness. She died in 2018.

Rhodes transformed quaint depictions of human activity into ominous visions of its future. As we stand before the dangers of human activity more palpable now than at any other point in the last few millennia – heat, emissions, endangerment creeping ever closer – Rhodes' work continues to gain urgent relevance. We peer closely into her canvas to survey the landscape, active participants in, and contributors to, the very sites that lay before us.

Ashley Tan, freelance writer

'Carol Rhodes: See the World' at Glasgow International was open between 11th June until 4th July 2021