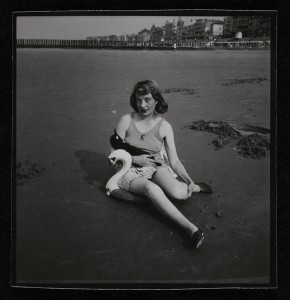

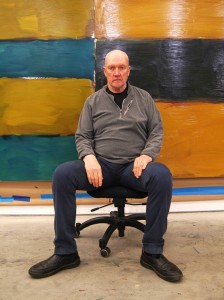

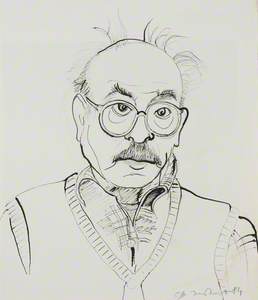

Terry Frost left school at 14 and got a job at a bicycle shop in Leamington. He then worked at a manufacturing company before joining the army. During the Second World War, Frost served in Greece, France and the Middle East before being captured in Crete in 1941. As a prisoner of war in Stalag 383, Bavaria, he met the painter Adrian Heath. Heath had seen the portraits Frost was doing of fellow prisoners (on hessian pillows) and encouraged him to think of art as his vocation.

© estate of Terry Frost. All rights reserved, DACS 2025. Image credit: National Army Museum

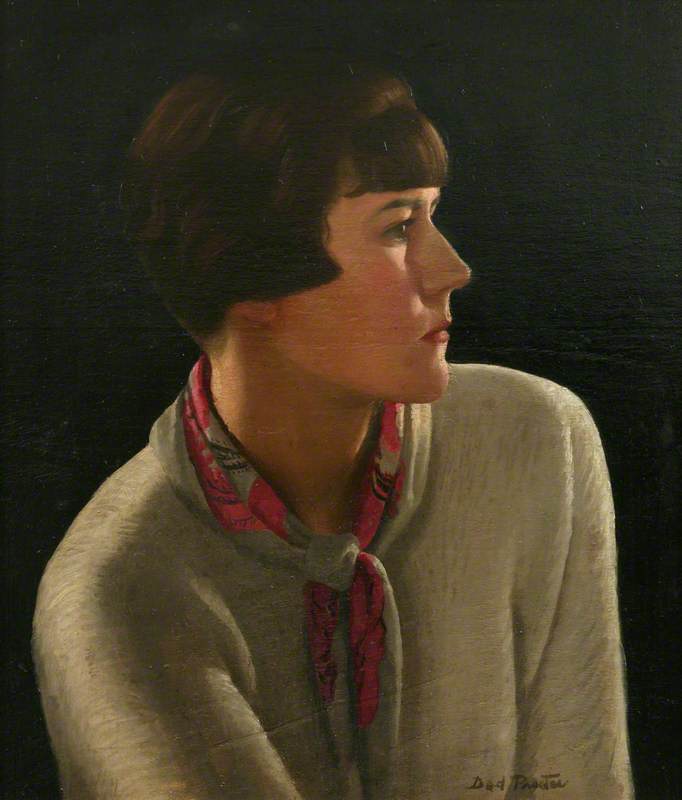

Sergeant Ernest (‘Ernie’) Little, 5 Buffs, as a Prisoner of War in Germany or Poland 1944

Terry Frost (1915–2003)

National Army MuseumTalking in later life about his time as a prisoner of war, Frost said: 'In PoW camp I got tremendous spiritual experience, a more aware or heightened perception during starvation, and I honestly do not think that awakening has ever left me.'

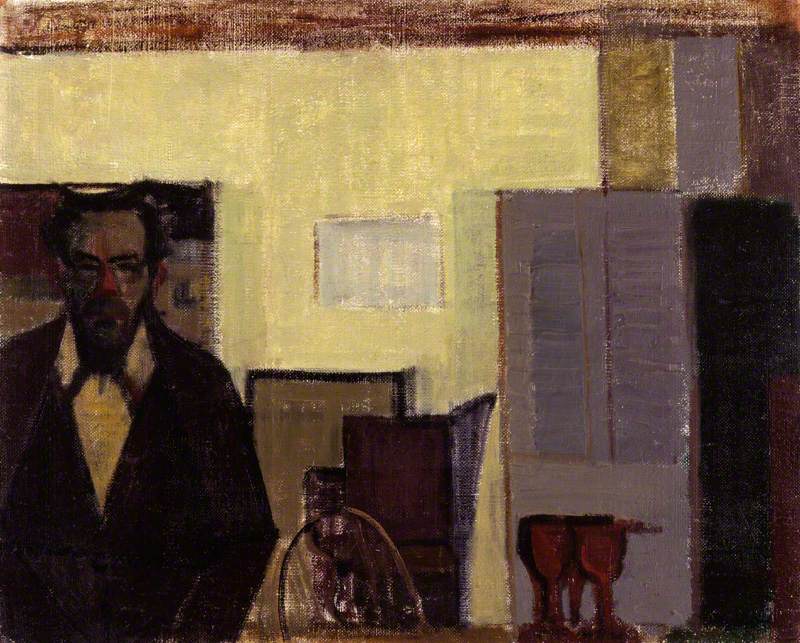

By the time Frost went to art school he was 32 and on an ex-serviceman's grant. He chose Camberwell School of Art where he was taught by William Coldstream. Coldstream was famous for running a methodical and disciplined life class and, according to Adrian Heath, Coldstream would be able to give the young man's enthusiasm some 'classical control'. He was also taught by Victor Pasmore, whom the aspiring artist described as 'my God'.

By 1950, Frost and his wife had moved to St

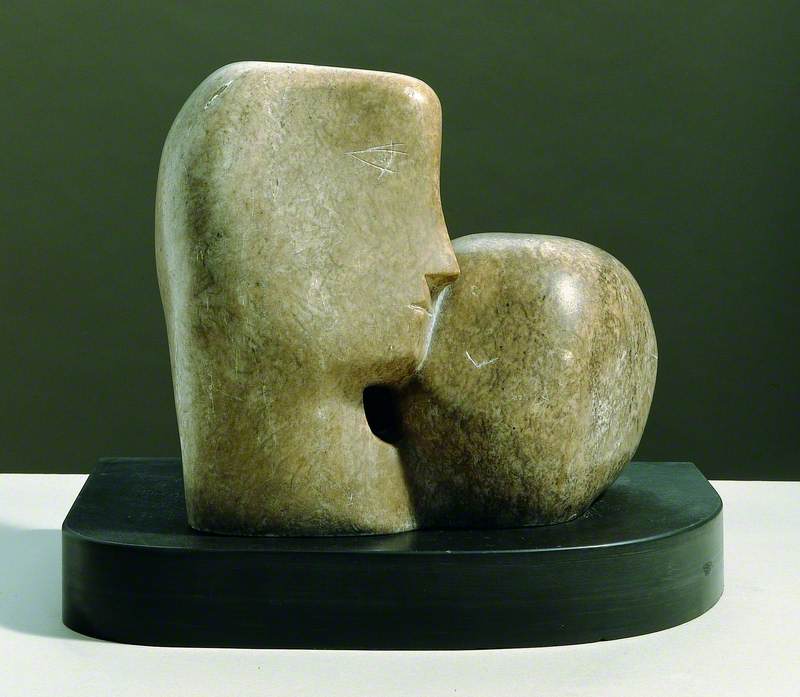

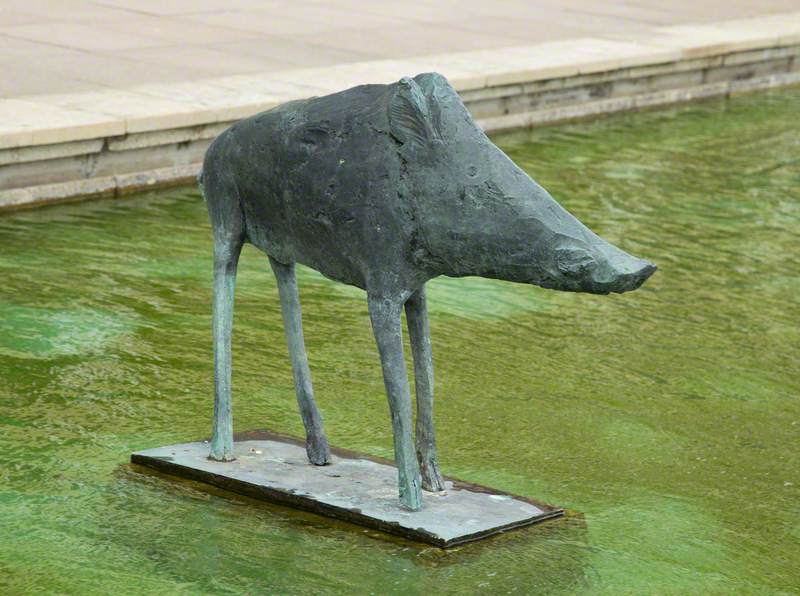

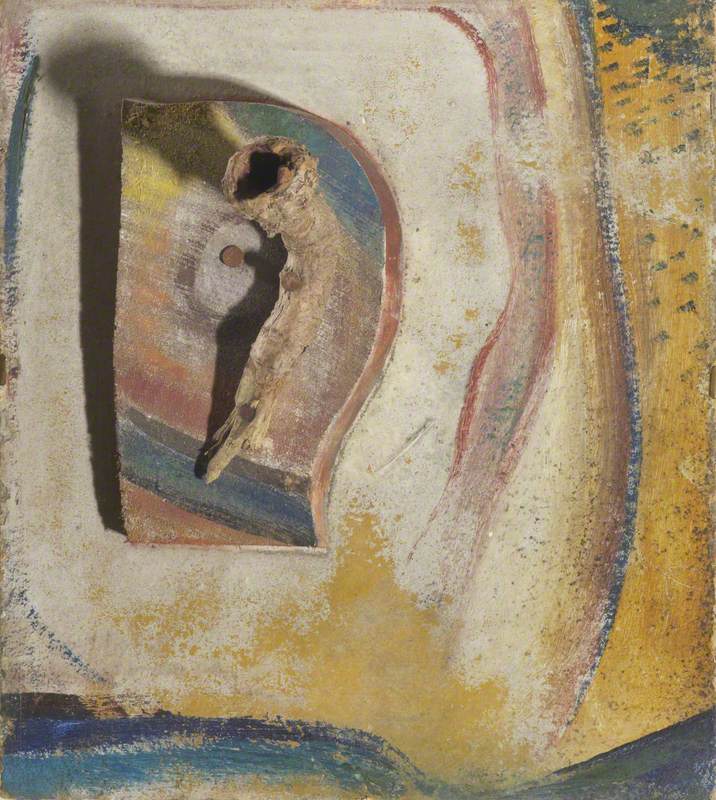

It was around this time that he worked as an assistant to Barbara Hepworth, another artist who had found inspiration in St Ives. She was working on her sculpture for the Festival of Britain – Contrapuntal Forms – and this experience gave Frost the idea for his later painted constructions.

In St Ives, Frost was surrounded by artists. In addition to Ben Nicholson and Barbara Hepworth, Frost became friendly with Peter Lanyon. He also travelled to Paris to study with Roger Hilton and continued to visit his old mentor Adrian Heath. Frost commented that he was delighted to be around like-minded people who were 'genuinely trying to do something'.

In 1960, Frost held his first one-man show in New York at Bertha Schaefer Gallery. This exhibition was a seminal moment in the artist's career.

He said of this experience: 'In New

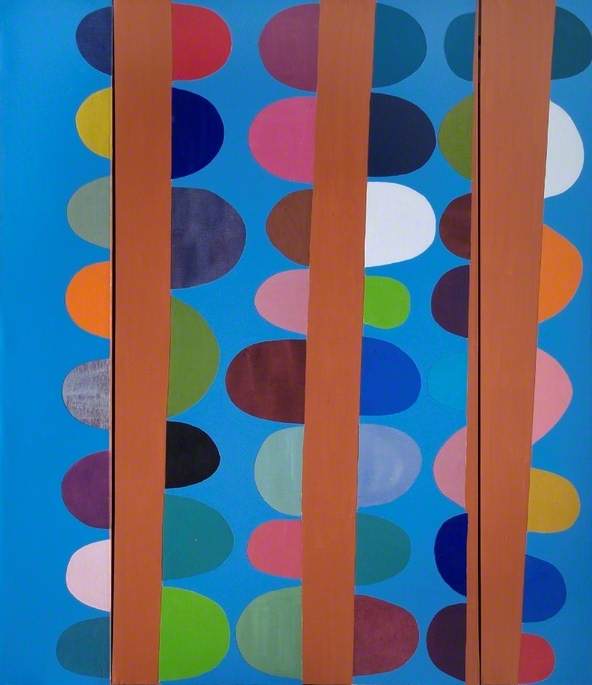

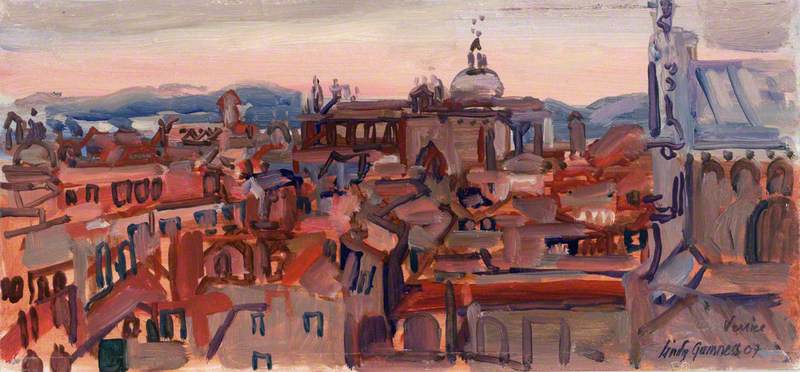

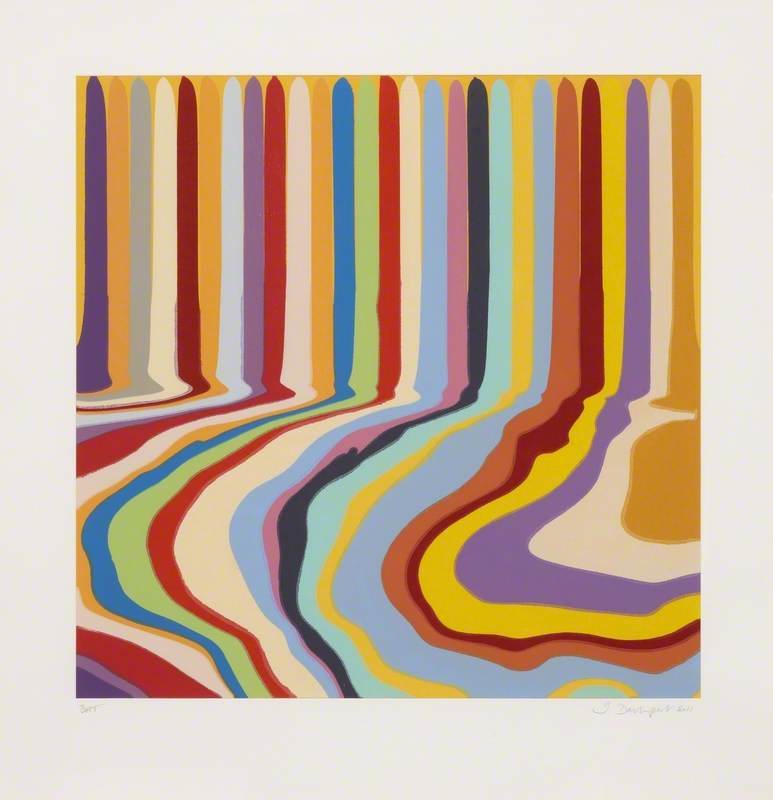

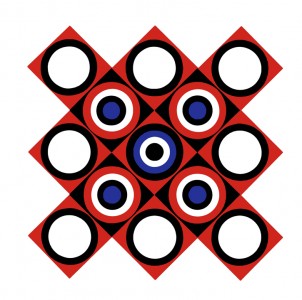

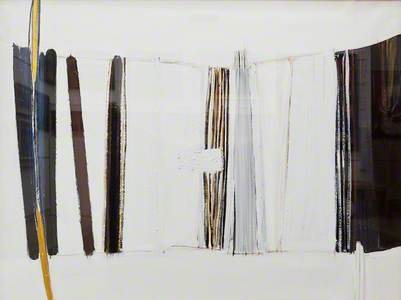

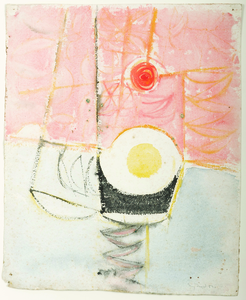

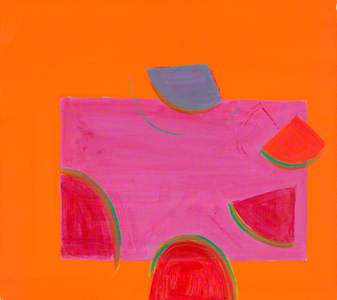

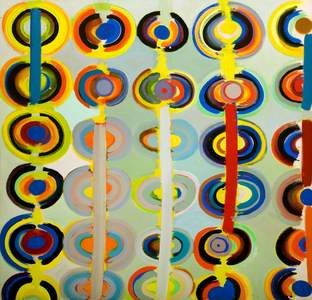

© estate of Terry Frost. All rights reserved, DACS 2025. Image credit: The Ingram Collection of Modern British and Contemporary Art

Terry Frost (1915–2003)

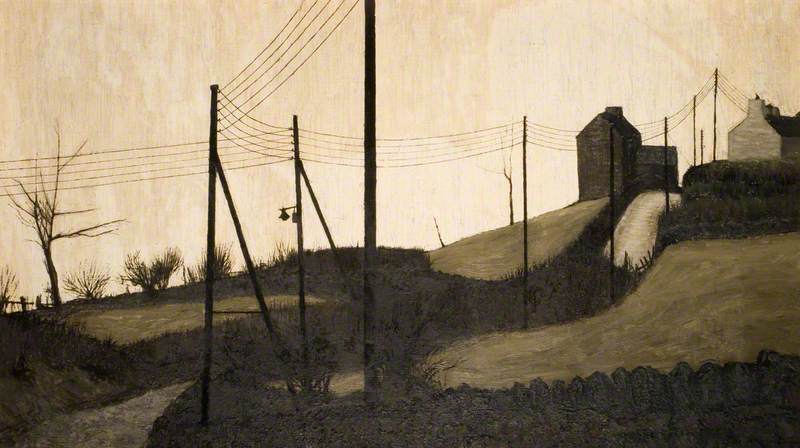

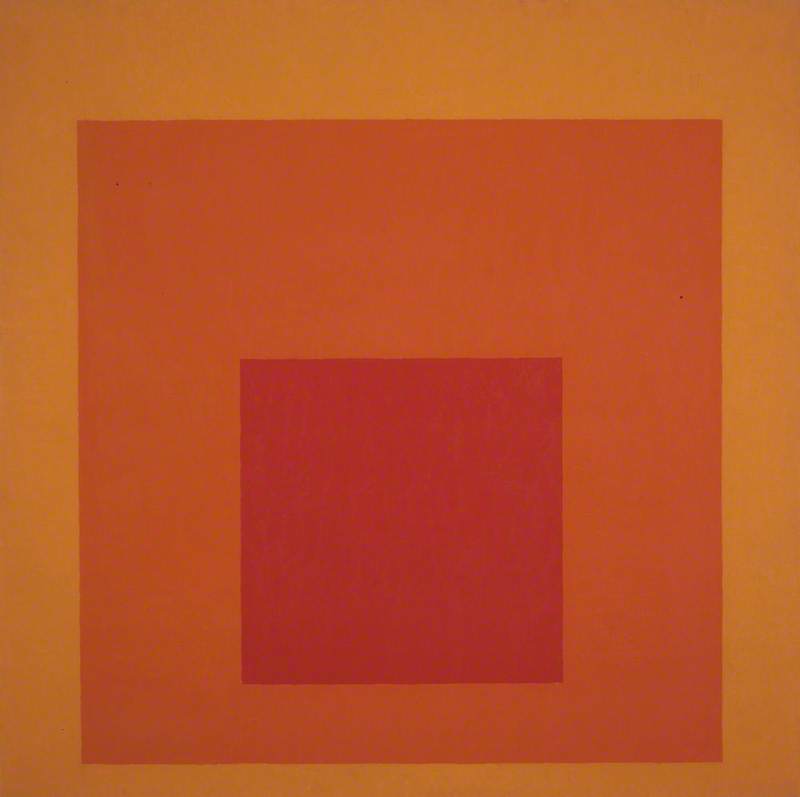

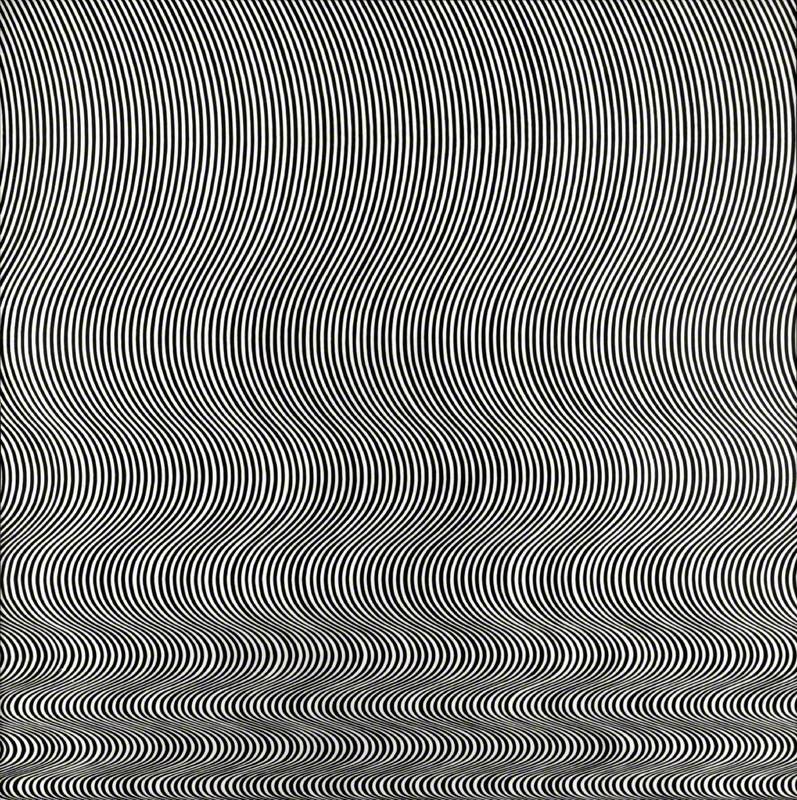

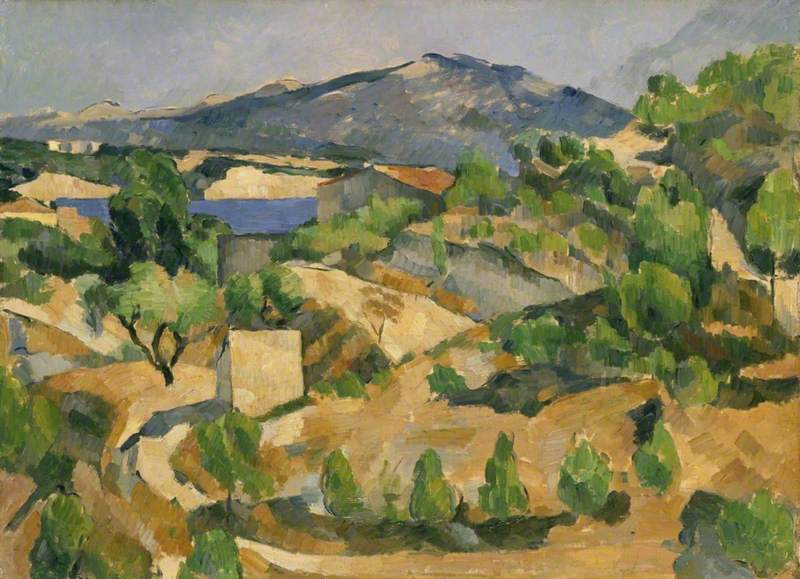

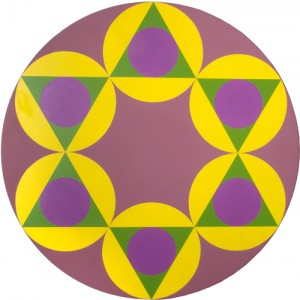

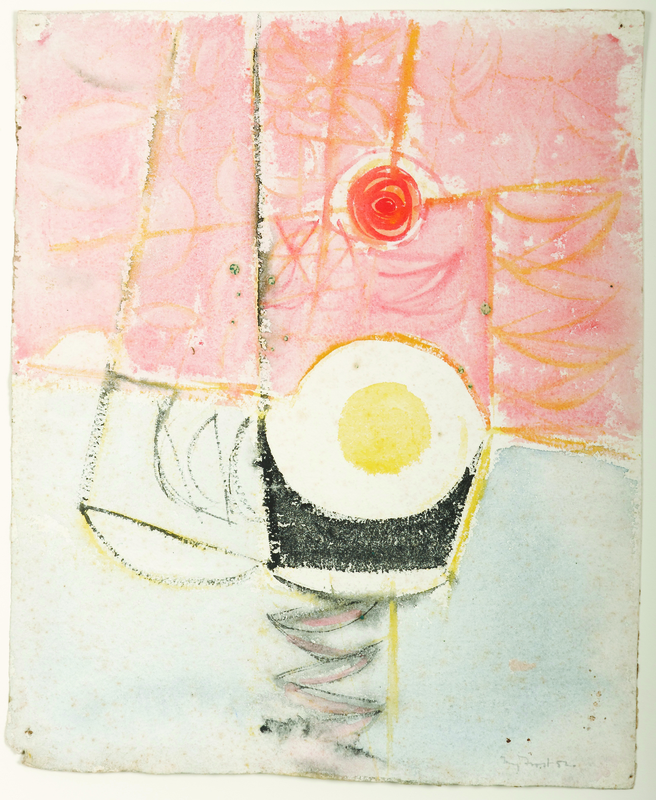

The Ingram Collection of Modern British and Contemporary ArtPursuing a career as an abstract painter had seemed a brave choice for a man who had come to painting later in life, and who also had a family to support (the Frosts had six children). But Frost believed that colour and shape could realise an image or feeling more successfully than figurative imitation. His works were grounded in the real world – his visual language was the landscape of Cornwall – and his works are full of colour and light. They speak of the pleasure of human existence, and Frost's own sensations and experiences. He had a sense of delight when looking at nature.

He said: 'A shape is a shape, a flower is a flower. A shape of red can contain as much content as the shape of a red flower. I don't see why one should have to have any association, nostalgia or evocation of any kind. It boils down to the value of the shape and the colour.'

Frost was also a gifted teacher. In 1956 he moved to Leeds to

He returned to Cornwall in the 1970s, setting up a home and studio in Newlyn where he remained until his death in 2003, always inspired by the Cornish light, and shapes of the landscape around him.

He was elected a Royal Academician in 1992 and knighted in 1998. As a teacher, Frost asked his students to remove their many pre-conceived notions of what things were like, saying, 'If you know before you look, you can't see for knowing.'

Jo Baring, Director of The Ingram Collection of Modern and Contemporary British Art