Terence Cuneo (1907–1996) was an artist of exceptional skill, range and popularity. He is probably best known today as the leading painter of railways. But in almost 6,000 paintings his work also embraced war and military history, state and public occasions, industry and technology, horses and wildlife, and portraiture.

His parents were artists, and met whilst studying under Whistler in Paris, and his uncle Rinaldo was also an acclaimed painter. His father, Cyrus, was a widely admired illustrator, who sadly died from blood poisoning in 1916 when Terence was just eight years old. The progress of Cuneo’s career was much influenced by these experiences.

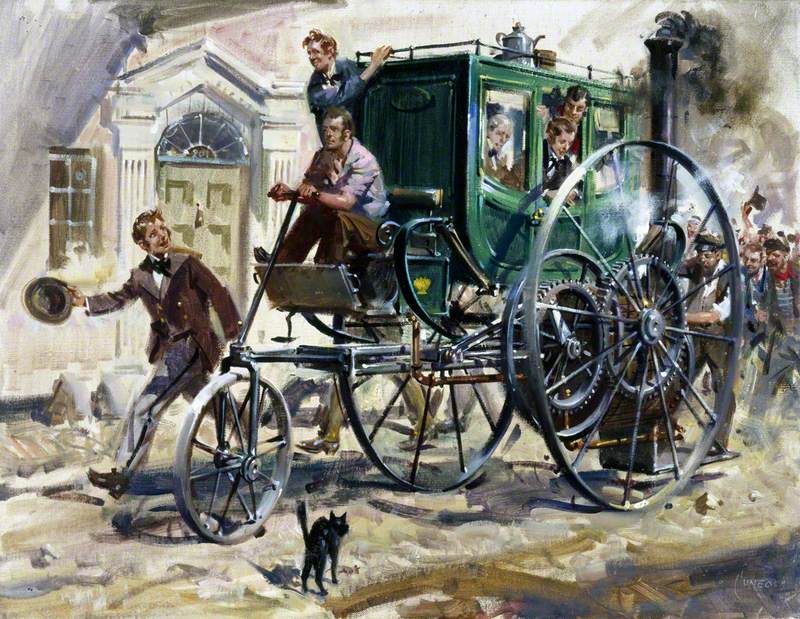

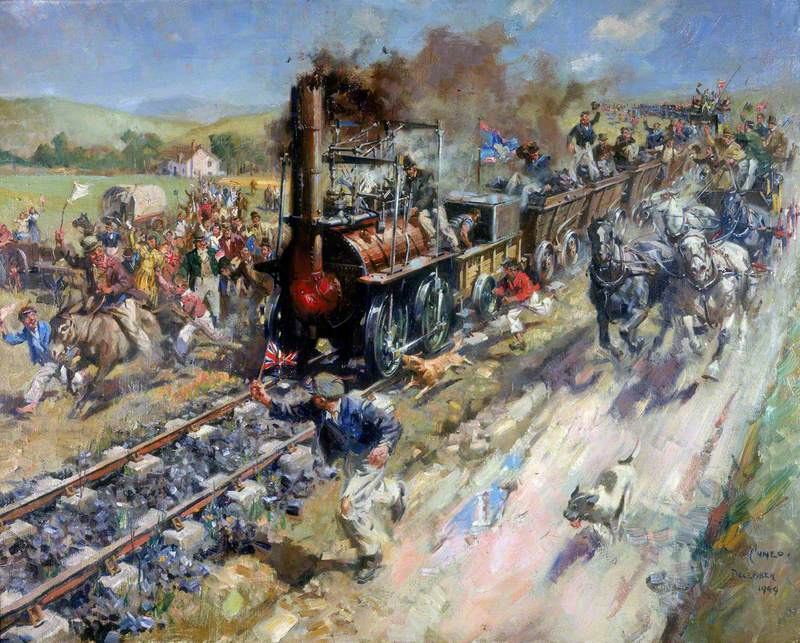

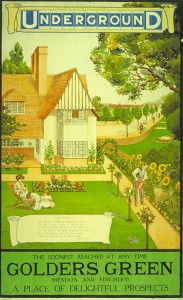

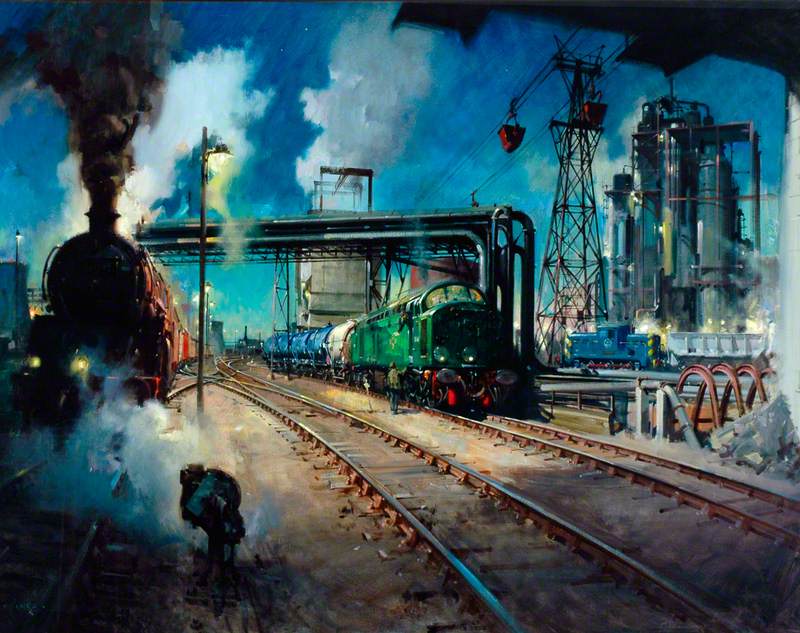

Cyrus gave his five-year-old son a model steam engine and so fired a lifelong passion. The avid child sketcher of steam locomotives became, early in his career, an illustrator of boys’ books and magazines, including railway-related publications. His big ‘railway’ break came with early commissions to create paintings and posters for the London, Midland and Scottish Railway, London and North Eastern, and the fledging British Railways. Commissions for the latter allowed him to capture the railways in the dying days of his beloved steam. Indeed, whilst clients sometimes wanted to feature the ‘new’ diesels and electrics, Cuneo often managed to make steam locomotives the most prominent.

South Grid Railway Sidings

(British Railways poster artwork 'Service to Industry') 1962

Terence Tenison Cuneo (1907–1996)

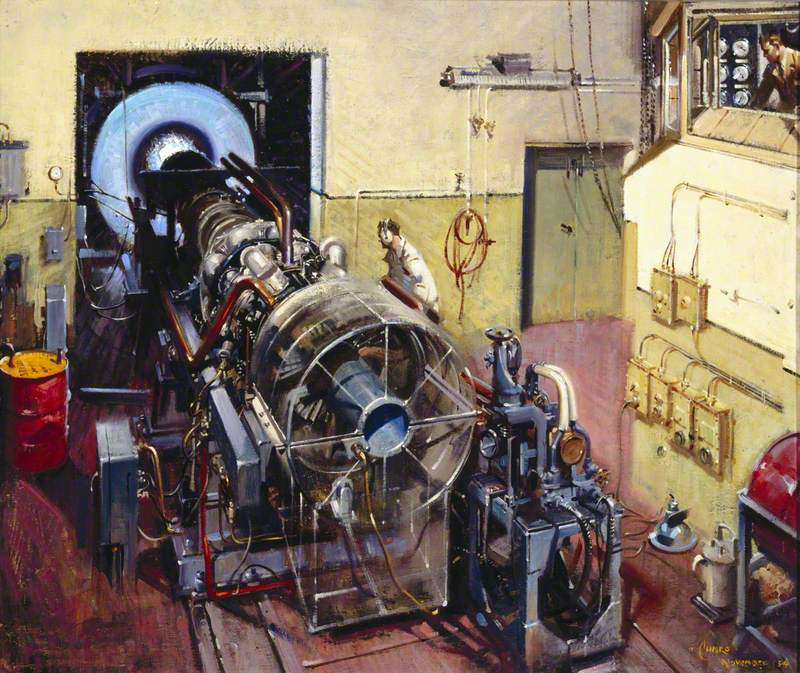

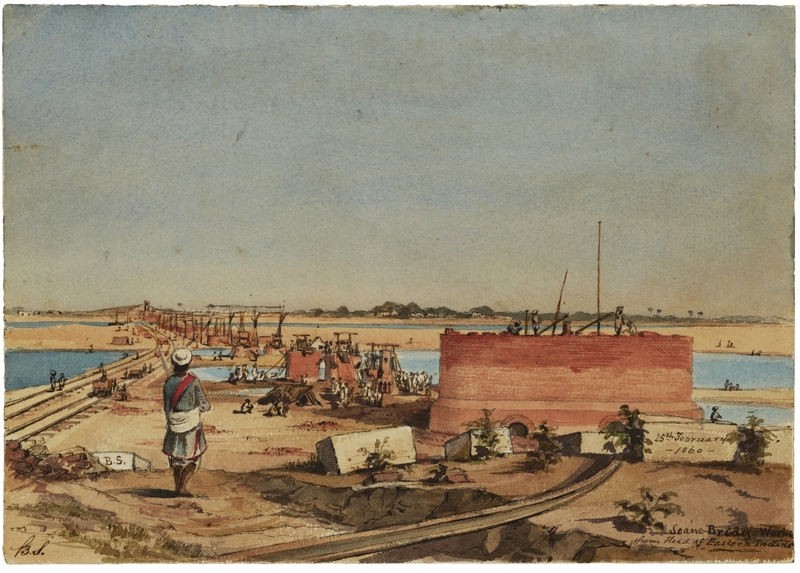

During the Second World War he was commissioned regularly by the Ministry of Information and the War Office, and later by the War Artists Advisory Committee, to create a wide range of propaganda images and secret visual resources (such as studies of harbour quay constructions at possible invasion ports). His first commission came from the Illustrated London News to sketch armament factories in France in 1940 and he escaped just as the Germans invaded. These projects gave him extraordinary exposure to working in tough conditions and capturing the spirit of men and women at work and in war, and the energy and appeal of new technologies. This relish for depicting the full range of industrial production meant that he was to secure a huge number of public and private commissions over the years. Cuneo had a great affinity with the army and was often asked to depict military history and leading commanders.

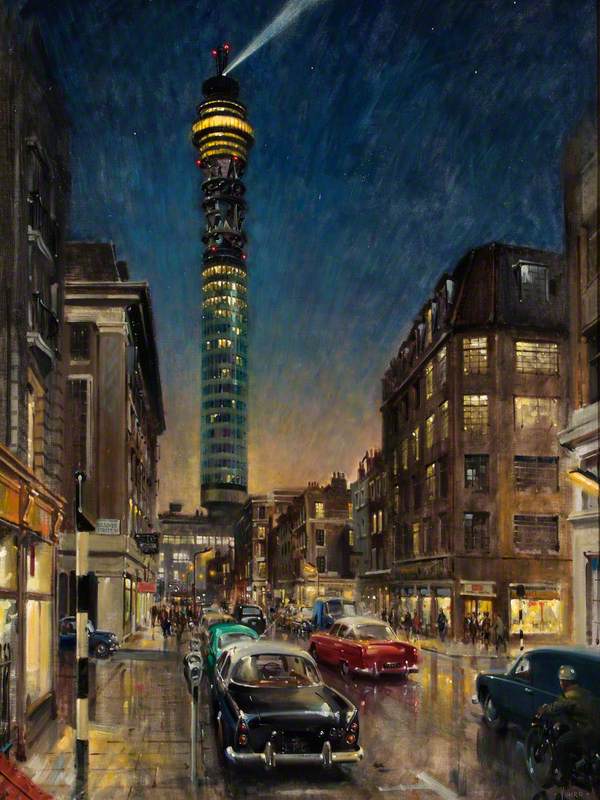

Finally, he secured the prestigious role of official artist for the Coronation of 1953. For several decades Cuneo was the artist of choice to capture major public occasions. He was valued for his flair in capturing the atmosphere, either joyful or solemn, of major state and private occasions, and the personality and profile of those attending. Each work shows the meticulous detail and method that is considered a hallmark of his style.

The Coronation Luncheon to Her Majesty Elizabeth II in the Guildhall, London, 12 June 1953

1953

Terence Tenison Cuneo (1907–1996)

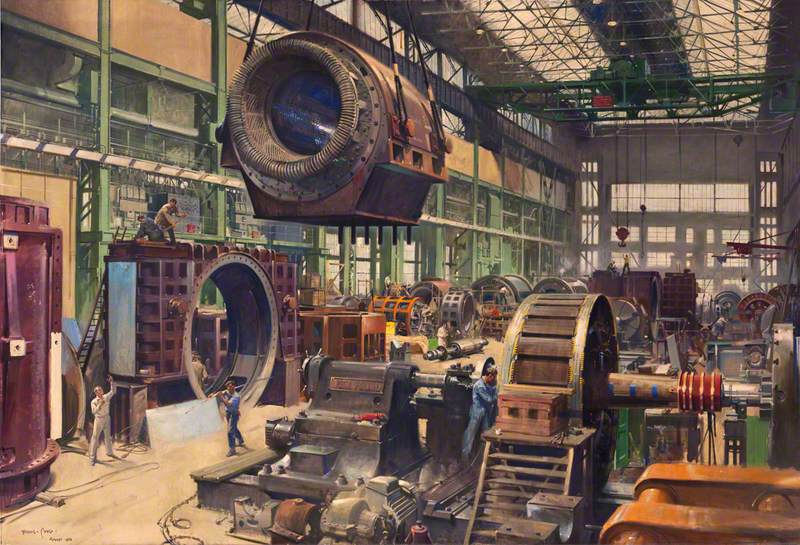

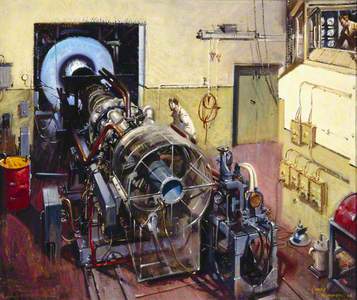

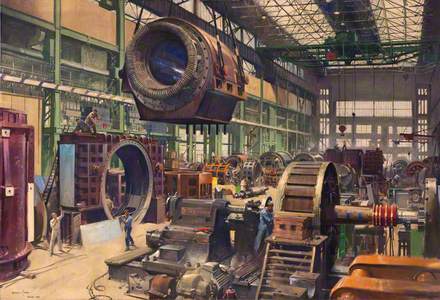

One of Cuneo’s largest and most inventive works is his painting of the General Electric Company’s works at Witton, Birmingham. It was commissioned by the Institute of Electrical Engineers for the Electric Power gallery at the Science Museum, which opened in 1957. The canvas was so large that it needed three men to stretch it to its frame, and Cuneo needed painting assistance from a surprising source. His friend Edmund Hockridge, a popular baritone and actor, was a talented amateur painter. Hockridge’s task was to complete the large blocks of colour and Cuneo had special brushes made because the canvas was so huge.

The picture is a Cuneo classic, with wonderful perspective and a diverse cast of characters. The picture also contains a portrait of a mouse, which was to become one of Cuneo’s trademarks. When he was painting one of his commissions for the Coronation, his cat brought a dead mouse into his studio. As relief from the formal painting, he painted a portrait of a mouse eating cheese which he later included in a show of his works. It was his first painting to sell at that show. Henceforth, this good luck symbol made a regular appearance in his works.

Ian Blatchford, Director, Science Museum Group