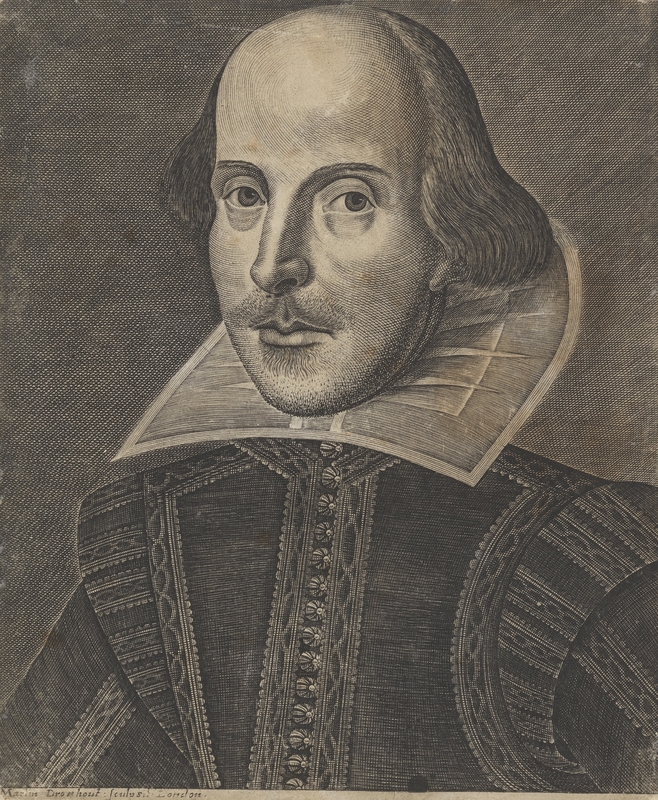

In The Palace of Art, a poem first published in 1832, Alfred Tennyson devised an imaginary 'pleasure-house', furnishing its short stanzas with descriptions of stained glass, mosaics, tapestries, and 'choice paintings of wise men' such as Dante and Shakespeare. 'Full of great rooms and small the palace stood,' he wrote, 'All various, all beautiful'. With hindsight, the poem looks like a literary precursor to the type of stylistic and historical assemblage that would come to characterise the Victorian age: it is a Crystal Palace or an Albert Memorial in verse, or even a fledgling museum.

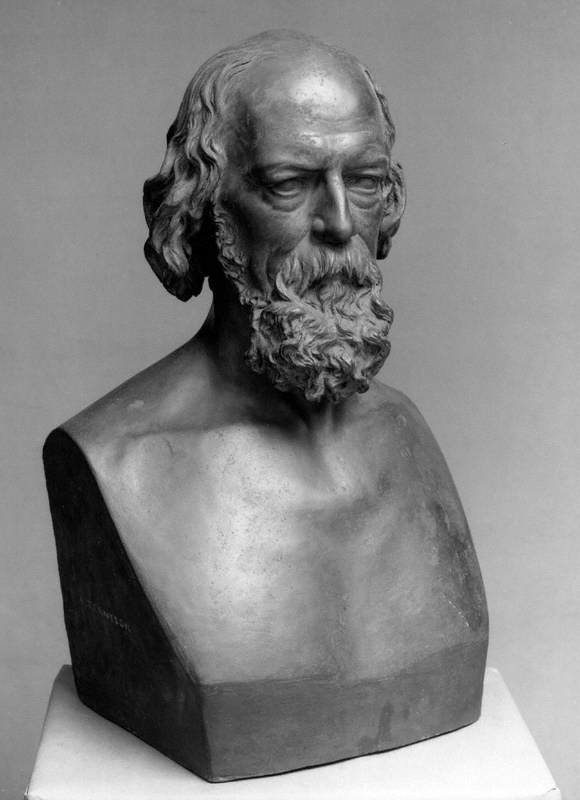

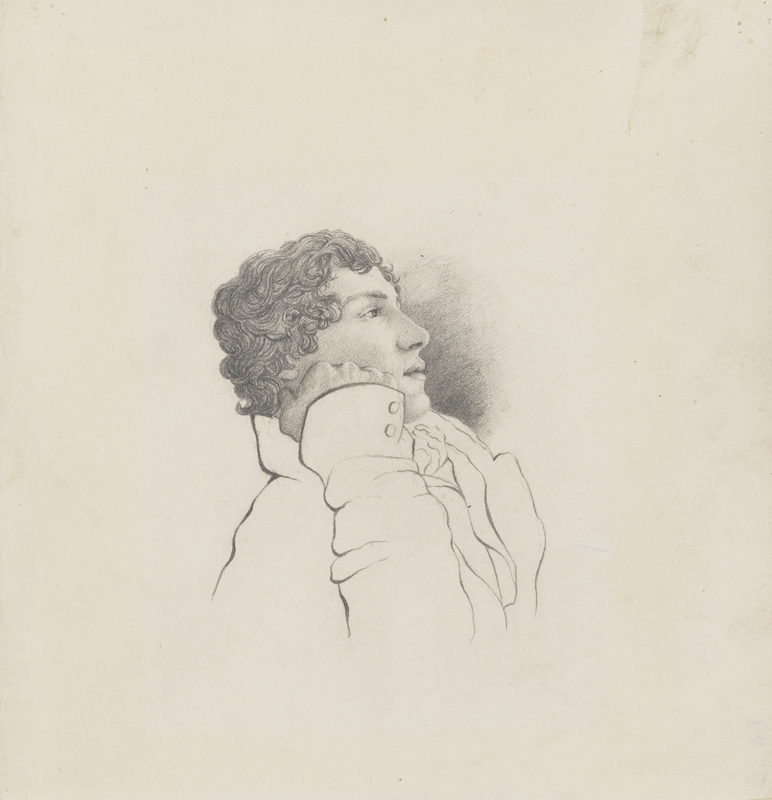

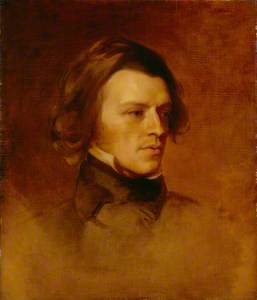

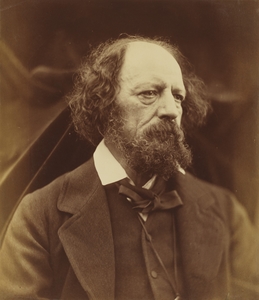

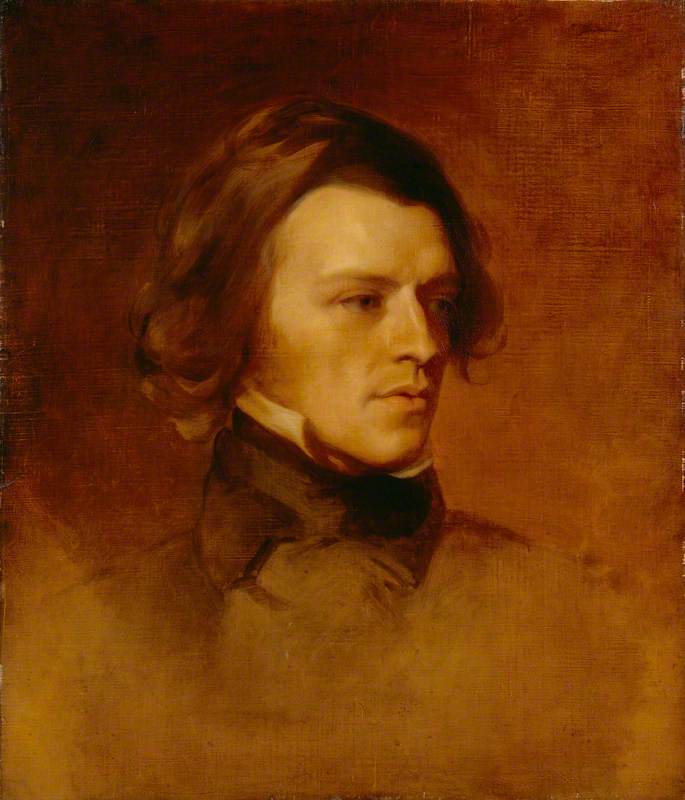

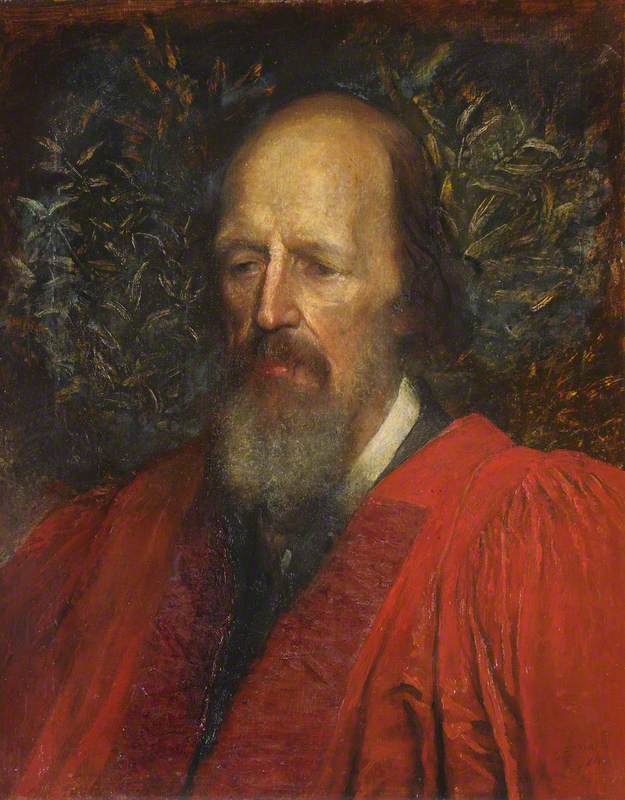

Alfred Tennyson, 1st Baron Tennyson

c.1840 & 1892

Samuel Laurence (1812–1884) and Edward Burne-Jones (1833–1898)

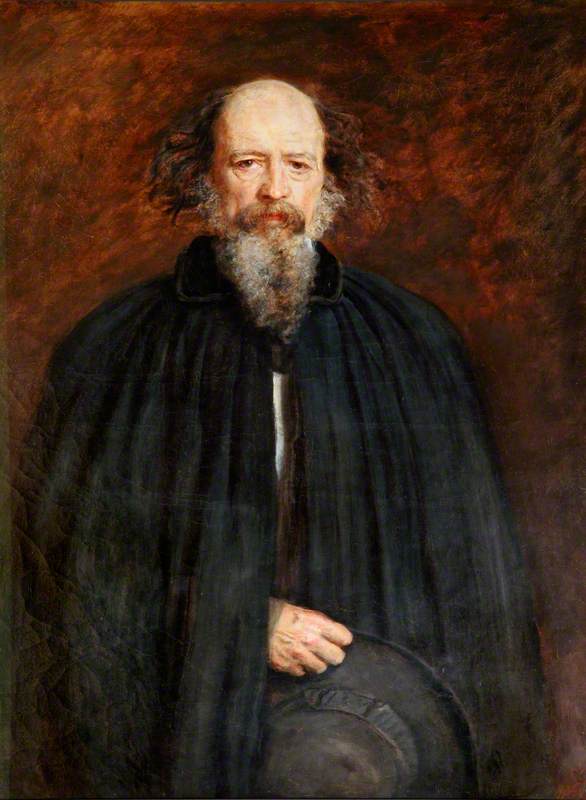

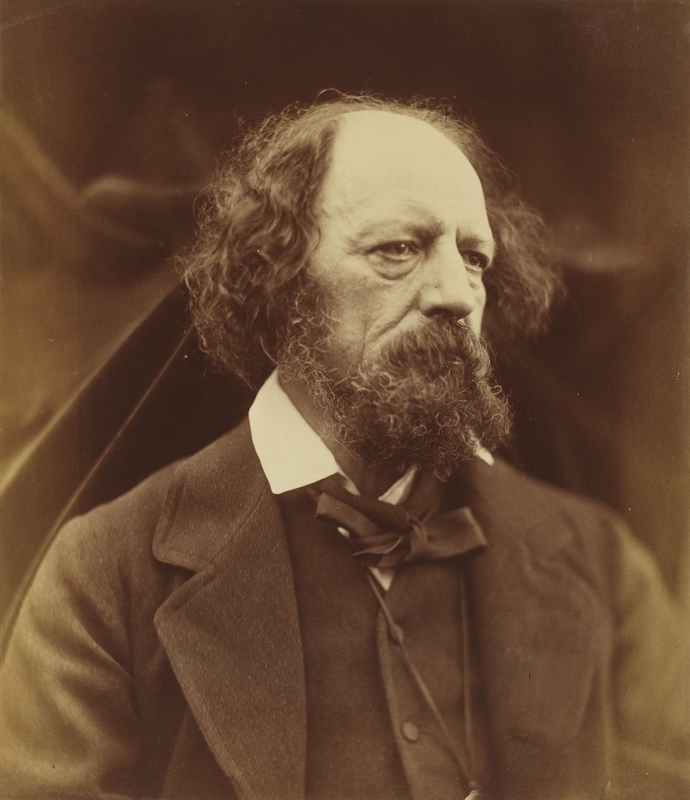

What Tennyson could not have known, at this early stage in his career, was how swiftly his poems would become a favoured subject for artists in the decades that followed. And not only that, for during his lifetime, the poet's own image would come to feature in the pantheon of great men (for they were almost all men) who were venerated by the Victorians for their cultural achievements.

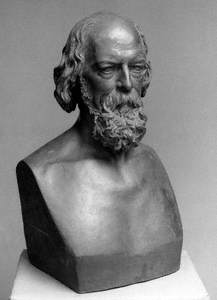

An article in the Magazine of Art in early 1893, just months after the poet's death, was dedicated to 'The Portraits of Tennyson', collating likenesses of a face that had become widely recognisable through reproduction in the illustrated press. The piece included a photogravure after Ernest Gustave Girardot's portrait, which was itself based on J. J. E. Mayall's famous 1864 photograph of the poet, and is now in the Usher Gallery in Lincoln.

A portrait by George Frederick Watts at Trinity College, Cambridge, painted late in the poet's life, catches how Tennyson would eventually unite the seemingly irreconcilable positions of being both a keystone of the establishment (as poet laureate and latterly a peer, depicted here in academic robes) and a remote, even mystical outsider. For all that he is being honoured in this portrait, the poet's eyes are downcast, as if his mind is elsewhere, and a halo of leaves – presumably laurels – sprout wildly around him. For others, Tennyson's official and orphic aspects never quite matched up: 'Tennyson was not Tennysonian,' wrote Henry James, after encountering the poet at a dinner party in 1877.

Alfred Tennyson (1809–1892), 1st Baron Tennyson, Honorary Fellow (1869), Poet Laureate

1890

George Frederic Watts (1817–1904)

Besides Shakespeare, no English poet can have provided inspiration for so many paintings and illustrations, and certainly none have done so during their own lifetimes. Tennyson's poetry spawned several important publications, so far as the history of illustrated books is concerned, in which artists envisaged the poems in ways that played a significant role in how their lines became ingrained in the wider cultural imagination.

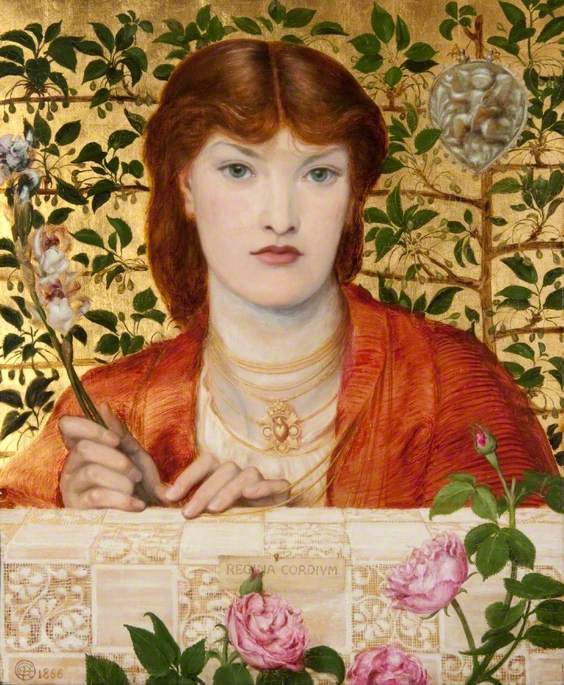

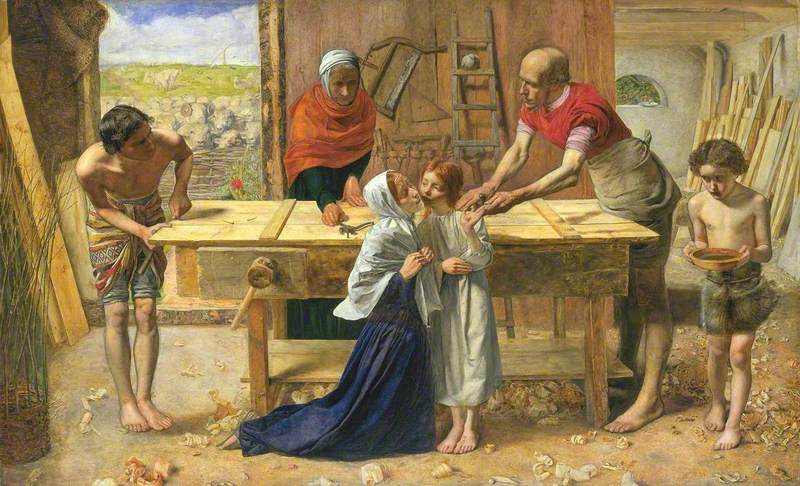

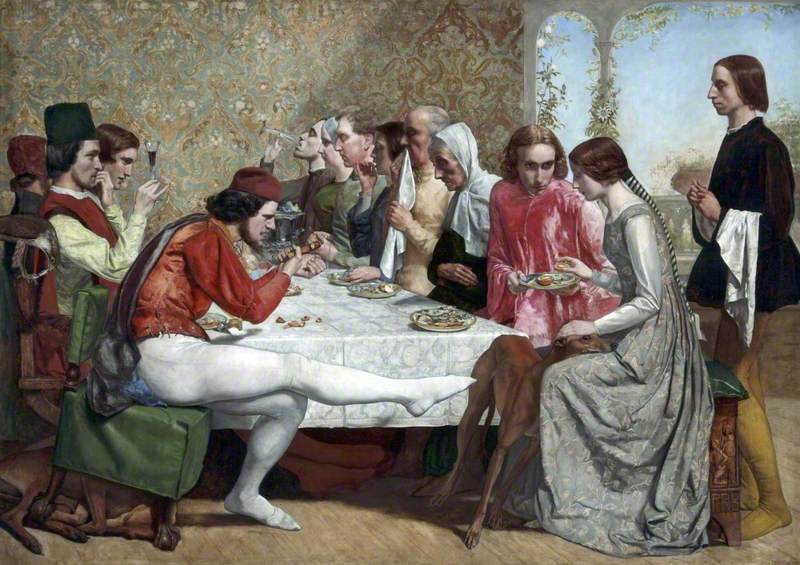

These included the 'Moxon Tennyson' (1857), named for its publisher Edward Moxon, in which the early poems were illustrated by wood-engravings by D. G. Rossetti, J. E. Millais and William Holman Hunt, the leading figures of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, as well as by more conventional artists such as William Mulready and Daniel Maclise. (Tennyson, who had encouraged Moxon to commission the more radical artists, later berated William Holman Hunt for his interpretation of The Lady of Shalott, which would become the basis for Hunt's painting of the poem some 30 years later: 'why did you make [her], in the illustration, with her hair wildly tossed about as if by a tornado?')

And then there was the illustrated Idylls of the King (1875), for which Julia Margaret Cameron provided a celebrated series of photographs – putting poetry in touch with this most new-fangled of art forms, even as photography seemed to spool back, via the towers and tourneys of Tennyson's Arthurian epic, into the medieval past.

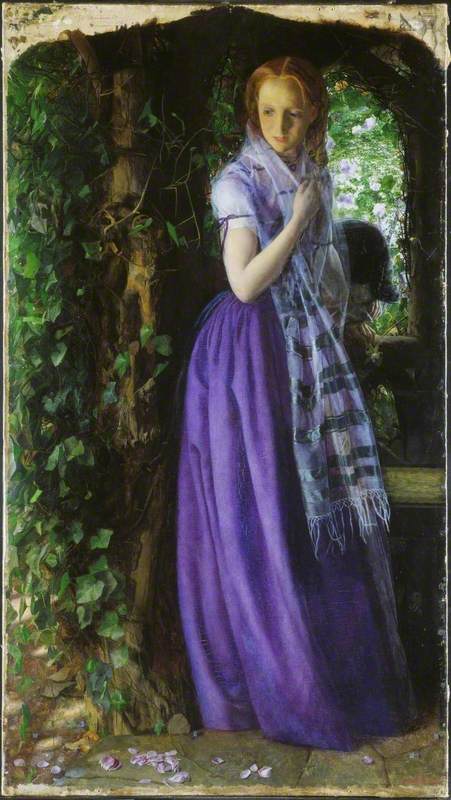

But it was in the field of painting that Tennyson's poems returned most insistently, providing subject matter (as well as justification) for both the type of enigmatic scene beloved by the Pre-Raphaelites and their followers, and the moralising settings of less radical genre paintings.

Probably most well known are John Everett Millais' Mariana, first exhibited in 1851, and John William Waterhouse's versions of The Lady of Shalott, particularly the 1888 work that has its protagonist preparing to unmoor, her embroideries trailing in the water, to begin her deathly drift towards Camelot.

Such paintings encapsulate what was perhaps most pictorially appealing about Tennyson's early poems for these artists: their sense of being stalled, that is, and their combination of stillness and foreboding. Stopping in front of these paintings, it is as if the Tennysonian air were too thick for his figures to advance through. 'She only said, "My life is dreary, / He cometh not," she said; / She said, "I am aweary, aweary, / I would that I were dead!"'

The Lady of Shalott

(from the poem by Tennyson)

John William Waterhouse (1849–1917)

It was Tennyson's first volumes, of 1830 and 1832, that proved most popular for artists drawn to his verse, at least until the publication of the first volume of Idylls of the King in 1859.

Hence not only the various Ladies of Shalott and Marianas, but paintings inspired by 'Mariana in the South' and 'The Miller's Daughter', too.

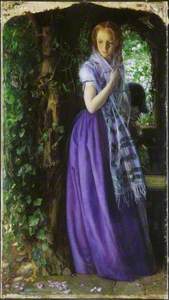

The Miller's Daughter, from Tennyson

1859

John Alfred Vinter (c.1828–1905)

A quotation from the latter was printed in the catalogue that accompanied the display of Arthur Hughes' April Love at the Royal Academy in 1856, like an extra coating of pathos added to its inscrutable scene of (possibly) lost love.

A less well-known vision is the reimagining of The Lady of Shalott by the Dutch artist Matthijs Maris, painted in c.1879–1885 and now in the Burrell Collection in Glasgow.

This shows a barely defined, almost monochrome figure, which hauntingly evokes the draining energy of the poem's tragic heroine.

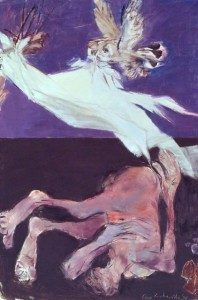

The popularity of Idylls of the King as a subject was part of a broader Victorian obsession with all things Arthurian – the poem, or series of poems, is part of the cultural chainmail that includes some of the most important works by William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones, among others. By the time that Laura Knight produced a painted frieze based on the Idylls in 1901, however, the Tennysonian mood was beginning to feel dated.

Idylls of the King (Balin and Balan, ii)

(4 of 6) c.1901

Laura Knight (1877–1970)

The stylised figures and landscapes of these six paintings reflect the growing influence of the Arts and Crafts movement, and a move away from dreamlike medievalism towards something sturdier and more practical (the friezes were acquired by the Irish sculpture Oliver Sheppard and his wife Rosalie Good, and hung in a room populated with Arts and Crafts furniture).

Tennyson may have fallen out of fashion with the avant garde in the first half of the twentieth century, but his poetry remained a staple of the school curriculum – which is perhaps why his influence persists in post-war British painting. A recent painting by Gillian Ayres, Tirra Lirra (2013), takes up Sir Lancelot's snatch of song from The Lady of Shalott and finds cause to dwell on it (appropriately, the painting was later translated into a tapestry).

And then there is Howard Hodgkin's Come into the Garden, Maud (2000–2003), a large painting that captures so well Tennyson's great 'monodrama' about the inflated scale of desire; its exaggerated fields of colour, spilling on to the frame and applied like a giant's pointillist dashes, are caught between poise and disturbance. They are Tennysonian.

Thomas Marks, Editor, Apollo magazine