Body language is perhaps the most nuanced language of all. From the tilt of the head to the placement of the hand, a figure's pose has the ability to shape the narrative, mood or meaning of an artwork.

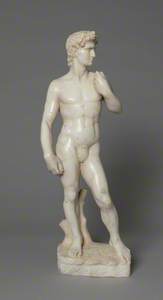

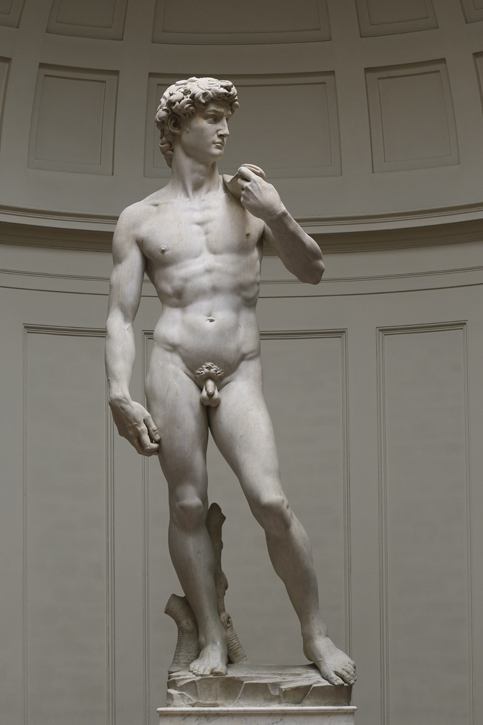

From the ancient Greek invention of 'contrapposto', famously found in Michelangelo's David, to the Hellenistic pose of the crouching Venus, Western art history has consistently reinterpreted poses from the classical world.

David

1501–1504, marble sculpture by Michelangelo (1475–1564)

Let's explore the other ways in which painters and sculptors have powerfully communicated the emotions and stories behind their subjects through the subtle art of body language. By doing this, we can begin to uncover new layers of meaning in artworks.

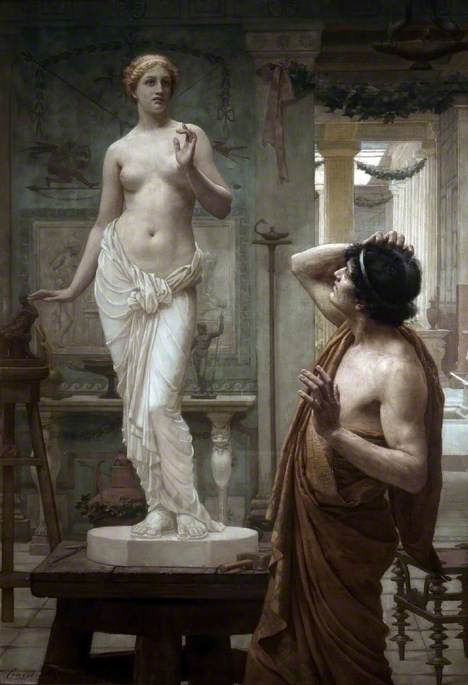

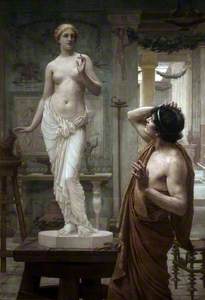

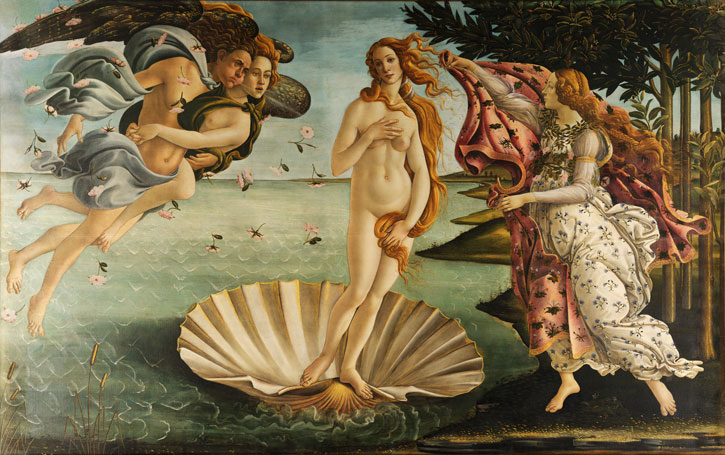

Pudica

Formally known as the 'Venus pudica', this stance features a woman – typically Venus the Roman goddess of beauty and fertility – covering her genitals and breasts with her hands whilst standing or reclining.

The term originates from the Latin 'pudendus', which refers to external genitalia and also implies shame, though it has been translated to mean 'modest Venus'. The ancient Greek sculptor Praxiteles created one of the first representations of the pudica with his Aphrodite of Knidos, a fourth-century BC life-sized sculpture of the goddess. Yet it was Sandro Botticelli who created the most iconic representation of the Venus pudica, found in his fifteenth-century painting The Birth of Venus.

The Birth of Venus

c.1485, tempera on canvas by Sandro Botticelli (1444/1445–1510)

The positioning of Venus' hands over her private parts purposely draws more attention to the concealed parts of her body. Contrary to being modest, the pose further emphasises Venus' sexuality and conveys her role as the goddess of beauty, love and fertility.

Unsurprisingly, the suggestive placement of Venus' hands has been assumed by artists to imply lewd action. Immediately after it was painted around 1534, the Venus of Urbino by Titian was criticised for implying female masturbation.

Venus of Urbino

(after Titian) 1823

William Etty (1787–1849)

The direct eye contact with the viewer alongside the figure's seductive pose, Titian's sensual rendering of the pudica implied promiscuity. The pudica pose has since been continued and sometimes inverted by artists in successive centuries, as seen in Manet's nineteenth-century Olympia.

Olympia

1863, oil on canvas by Édouard Manet (1832–1883)

Detached from its origins and embodiment of sexual vulnerability, the pudica came to demonstrate emboldened sexuality (and even liberation), thus returning the power of sexuality back to Venus.

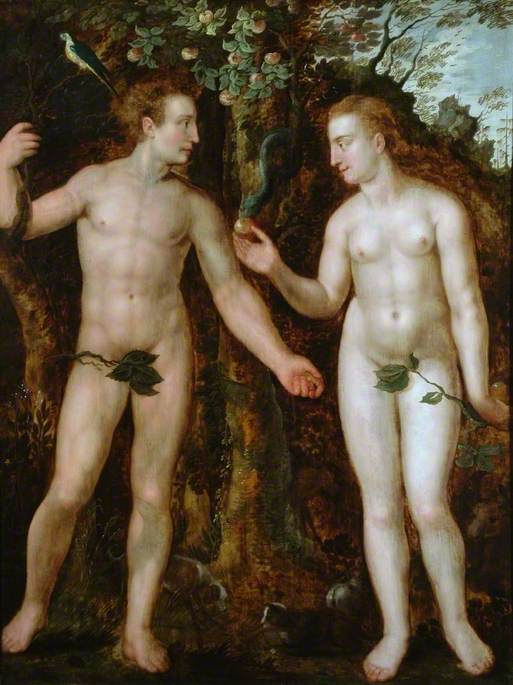

Yet the pudica remained connected to shame and humiliation ('pudendus' comes from a Latin word meaning 'to be ashamed'). During the Medieval and Renaissance eras, representations of the biblical Eve continued to adopt the classical pudica, especially when illustrating Eve and Adam's expulsion from the Garden of Eden. In the words of Griselda Pollock, Eve's pudica pose reflected 'the embodiment of sins in general and female weakness specifically'.

The Expulsion from Paradise

c.1600–1610

Giuseppe Cesari (1568–1640)

The greater need for Eve to cover her private parts in shame in comparison to Adam is highlighted in paintings by Giuseppe Cesari and Peter van der Werff. In Van der Werff's eighteenth-century depiction, Eve covers her breast with her left hand, while Adam simply stretches his arms out in a startled manner – this juxtaposition in body language implies overwhelming shame on Eve's behalf.

The Expulsion of Adam and Eve

(copy after Adriaen van der Werff) early 18th C

Pieter van der Werff (1665–1722) (attributed to)

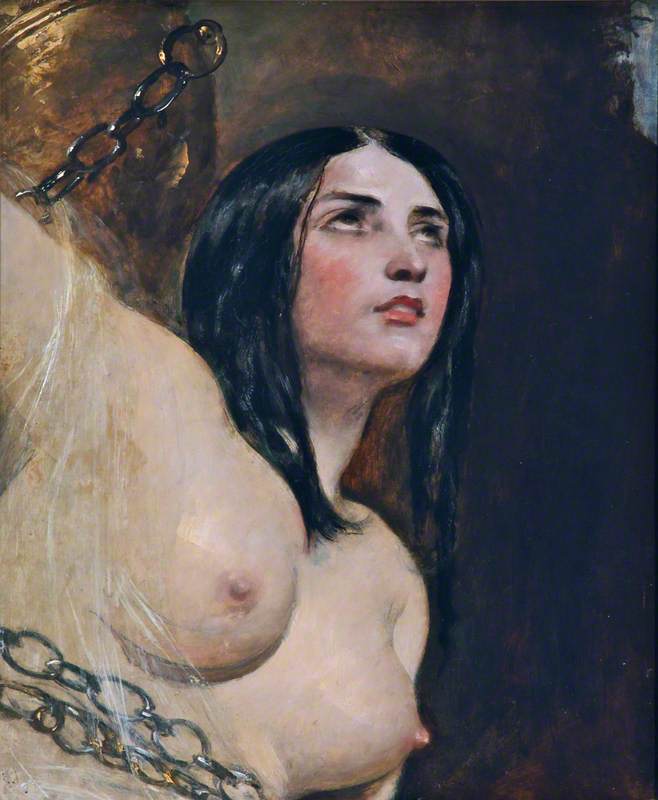

The pudica pose also lends itself to the narrative of the male gaze, evident in artworks depicting the biblical narrative of Susannah and the Elders, once captured by Artemisia Gentileschi. Capturing the moment she is approached by the men during her bath, Susannah's body language implies a desperate need to cover her body in alarm.

Gentileschi illustrates Susannah's fear through the tight grip on her body; her arms appear slightly elongated, exaggerating her need to protect herself. Moreover, unlike depictions of Eve and Venus, prying men are included, introducing the theme of voyeurism. Voyeurism, in tandem with the pudica, emphasises the objectification of Susannah and her powerlessness in this situation.

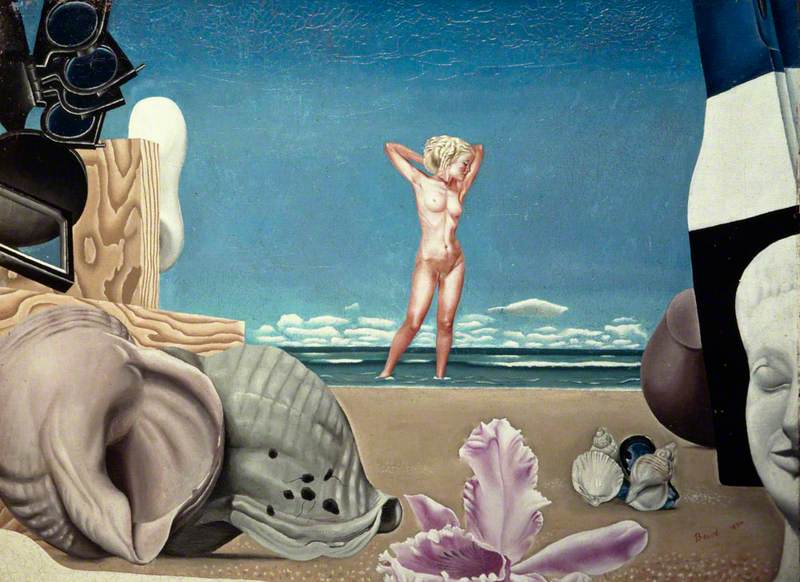

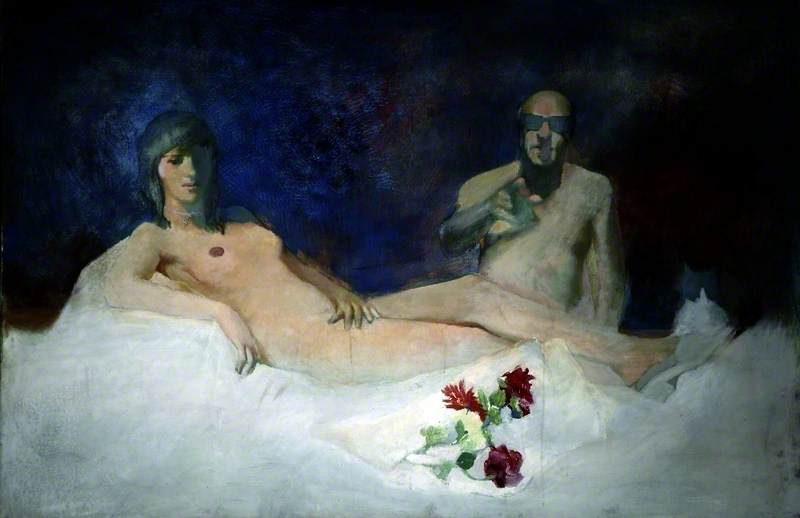

Odalisque

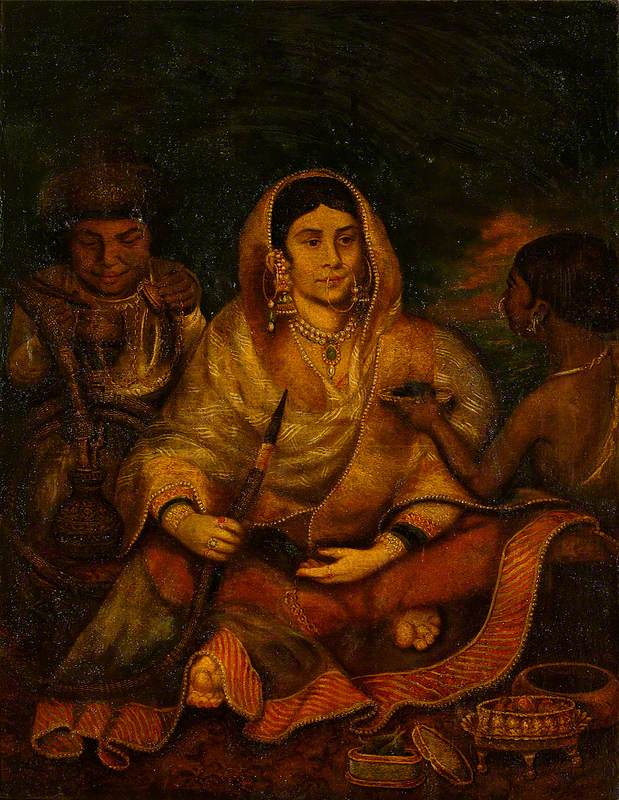

Derived from the Turkish odalik, meaning 'chambermaids', this pose is comprised of a woman reclining seductively on a divan before the viewer. The French term refers to concubines (or 'virgin slaves') from the Harems of the Ottoman Empire, a popular artistic subject matter during the Orientalist movement in the nineteenth century and perfectly captured in Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres' La Grande Odalisque.

La Grande Odalisque

1814, oil on canvas by Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres (1780–1867)

Typically, artists depicted the woman naked, exposed and outstretched, as a way of offering her whole body to the audience, almost as a sexual offering. The odalisque is well renowned for its purpose to satisfy the male gaze, which in today's context has become an increasingly contentious topic.

On the other hand, could it be argued that the pose of the odalisque implies female sexual liberation? In some depictions, the subject confronts the viewer's gaze, indicating that the subject has a certain degree of control over her body. She is aware of her voyeurs who admire her figure, and thus she wields power in her ability to capture their attention. In this sense, the subject is not straightforwardly objectified, neither is her body being used for pleasure unknowingly.

Regardless, many counter this idea, especially when reminded that the painted odalisque represents a fantasy of the male imagination. This pose is captured by the male artist for the male viewer, which has instigated contemporary feminists groups such as the Guerrilla Girls to challenge art history's perpetuation of the male gaze. The odalisque was appropriated and parodied in one of their most famous works, Do Women Have To Be Naked To Get Into the Met Museum? (1989), a work which continues to provoke and incite new conversations about the presentation of women in art.

Guerrilla Girls: "The Art of Behaving Badly" at kestnergesellschaft @kestnerHannover #kestnergesellschaft #GuerillaGIrls https://t.co/2tYviMqKBa pic.twitter.com/ciXaydHYtW

— e-flux (@e_flux) February 9, 2018

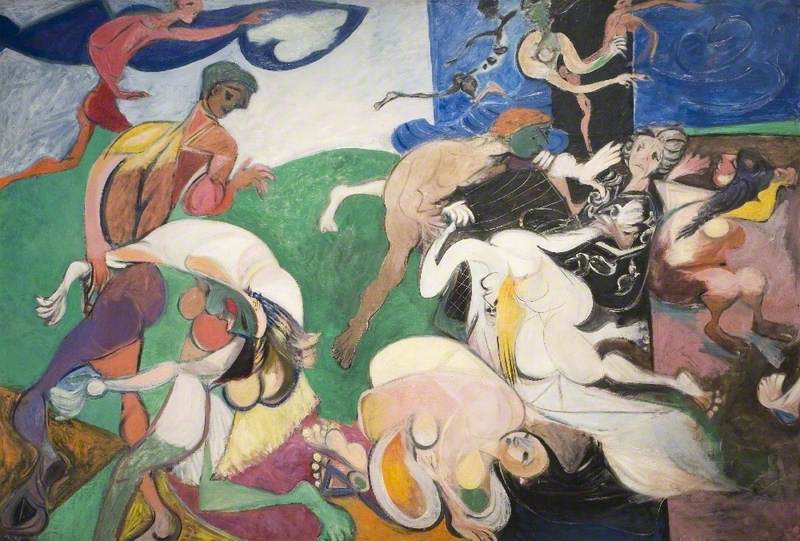

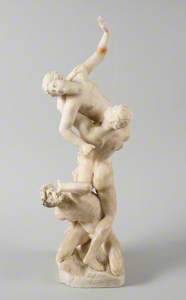

Serpentinata

The 'figura serpentinata', literally translating to 'serpentine figure', is a more dynamic pose. The figures are presented with their bodies twisted in a spiral, offering a chaotic composition. The sixteenth-century painter and theorist Giovanni Lomazzo stressed that the figura serpentinata may also be composed in a pyramid shape and typically will follow a general numerical proportion.

This pose originates from the Hellenistic marble sculpture Laocoön and his Sons, a sculpture that was praised for its ability to translate human agony into art. This nineteenth-century plaster replica of the Laocoön can be found in The Royal Academy.

The sculpture is based on mythology from the Greek Epic Cycle, in which the Trojan priest Laocoön and his two sons, Antiphantes and Thymbraus, are attacked by sea serpents. This macabre scene highlights themes of suffering, pain and death, seen through their tormented facial expressions and posture. Their contorted bodies emphasise the physical pain endured, as all three stretch out their limbs and fingers in overwhelming agony.

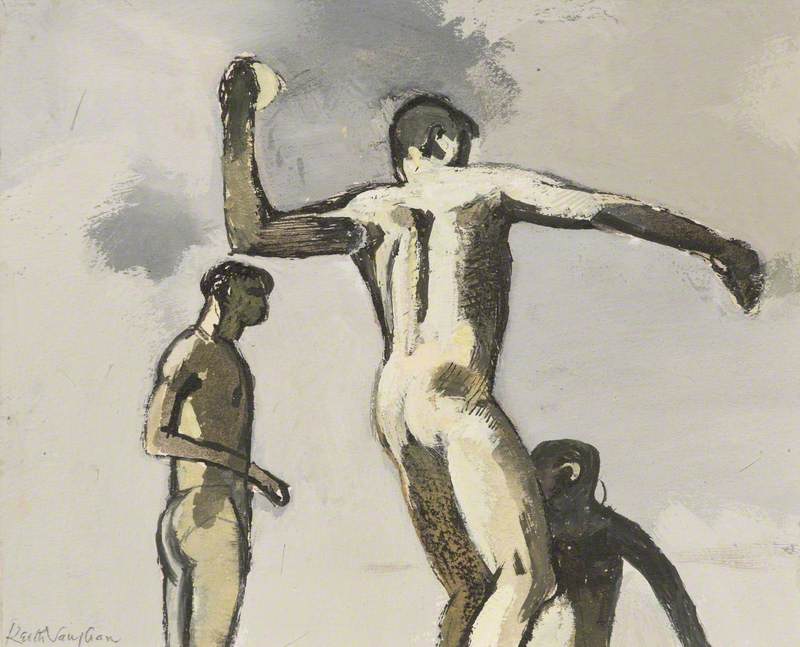

Modern depictions of the Laocoön use the serpentinata to exaggerate the chaos and anguish of this scene. In this work by the British twentieth-century painter John Keith Vaughn, the length of the men's limbs are elongated in order to dramatise the serpentinata in a crude manner, creating a disjointed and abstract composition.

Artworks depicting the Rape of the Sabine Women from Roman mythology tend to utilise the serpentinata in order to capture the women's pain and anguish. The extreme twists and turns of the figures express the palpable fear of the women; a lack of composure in their actions expresses their imminent abduction and struggle to be free.

Samuel Woodforde's illustration (after Poussin) further illustrates the tension of the scene through the strain in the muscles and clenched fists.

A Group from the Rape of the Sabines

(after Nicolas Poussin) 1812

Samuel Woodforde (1763–1817)

Modern interpretations depict the women and the abductors in a more crude manner, amplifying the violent nature of the myth. The sharp contortions of the body in Ceri Richards' The Rape of the Sabines from 1948, for instance, challenges glamorised classical depictions of the rape.

Adlocutio

The 'adlocutio' pose is famed for embodying control, power and leadership. This stance requires the contrapposto pose – a standing position whereby the weight of the figure is shifted on one leg, alongside a raised right hand and generally a pointed finger. Originating in ancient Roman art, it would typically be used to depict generals or orators addressing a large crowd.

Augustus of Prima Porta

c.1863–1899

Antonio Messina (active 19th C)

Augustus di Prima Porta is perhaps the most renowned example of adlocutio, and commemorates Augustus as Rome's greatest leader. He is shown to be powerful and commanding, yielding the attention of many whilst he addresses his soldiers after battle.

This power pose has been utilised by many historical figures of power and influence, including Jesus Christ in early Christian and Renaissance art. Commonly depicted in the adlocutio pose during the Resurrection, Jesus is presented as a revered divine figure whilst addressing all of humanity. His right hand gestures towards the sky and symbolises his divinity, reminding viewers and worshippers of his status as the son of God.

Adlocutio is also prevalent in many depictions of generals and leaders of the eighteenth century, heralding their military strength and power.

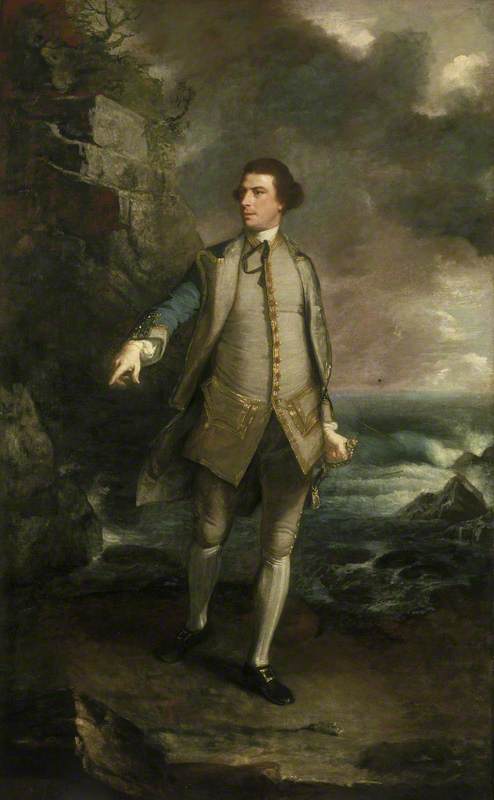

Captain the Honourable Augustus Keppel, 1725–1786

1752–1753

Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792)

For Britons during the French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars, portraiture relaying Britain's naval superiority became a common form of propaganda. Featuring an accompanying image of a ship at sea to which they both point at, their pose here reflects Britain's military dominance and prowess in the face of their enemies.

Captain Sir George Montagu (1750–1829)

c.1780–1790

Thomas Beach (1738–1806) (attributed to)

By analysing and deconstructing poses in art, it is revealed that the composition of figures plays a crucial role in the visual language of art. Whether it be to illustrate an image of seduction, anguish or control, a subject's posture holds the power to shape the impact and narrative of an artwork.

Avesta-Saule Zardasht, freelance writer