Stanley Spencer wished in effect to have two wives simultaneously, and it is clear that his second wife-to-be, Patricia Preece, collaborated in this idea. She also envisaged a ménage à trois between herself, Spencer and his former wife Hilda (née Carline), which would relieve Patricia of marital duties. Hilda had the sense to refuse. There followed a difficult period for Spencer: he had been divorced by his first wife, but for various reasons was not co-habiting with his second wife, whom he had married four days after his divorce in 1937. Patricia remained with her lifelong partner, Dorothy Hepworth (no relation of the sculptor, Barbara Hepworth).

In 1939, after a short period living on his own in London, Spencer began an affair with the artist Daphne Charlton. Although 18 years younger than Spencer, she provided warmth and nurturing to which he responded. Their affair was to last until 1941, although they remained in touch for the rest of his life. She was to feature in a remarkable series of paintings and drawings by Spencer inspired by their affair.

I first met Daphne on 7th December 1971, at a concert in the Royal Festival Hall – Colin Tilney playing Bach's 48 Preludes and Fugues. Spencer's ability to achieve a good likeness in portraiture has never been in doubt. I looked to my right, and from my knowledge of Daphne (1940), painted 31 years previously,

... he deliberately reduced her to tears each day, to get some emotion into her face. She claimed that nobody else could cause her to cry: 'I don't know how, he had that power.'

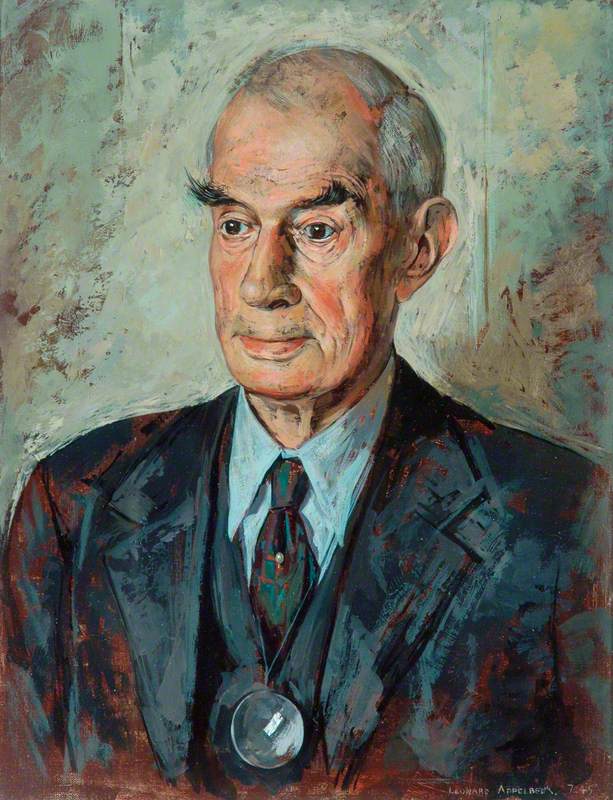

In June 1939, Spencer went to stay with Daphne and George Charlton at 40 New End Square, their home in Hampstead. George spent most of his professional life as a teacher of painting and drawing at the Slade. George was said to have proposed to many of his female pupils, but it was Daphne who accepted. They were married in

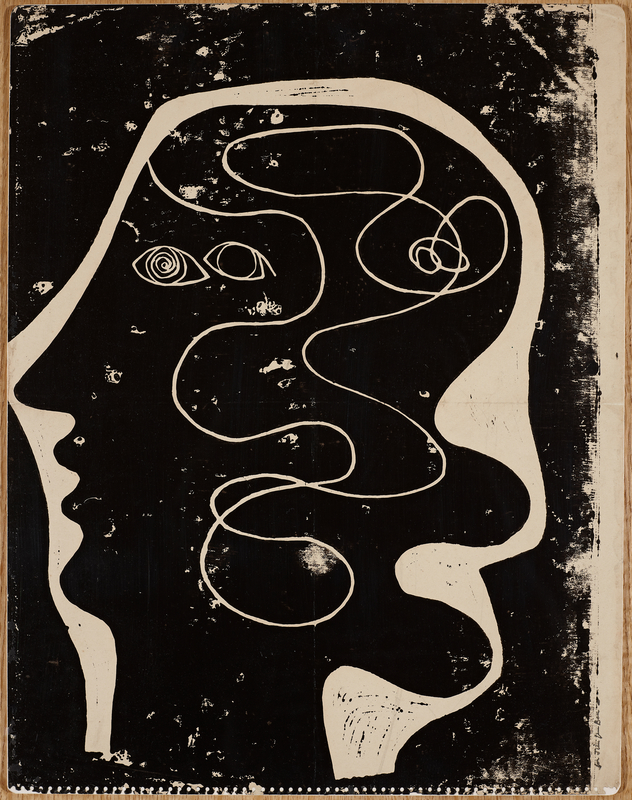

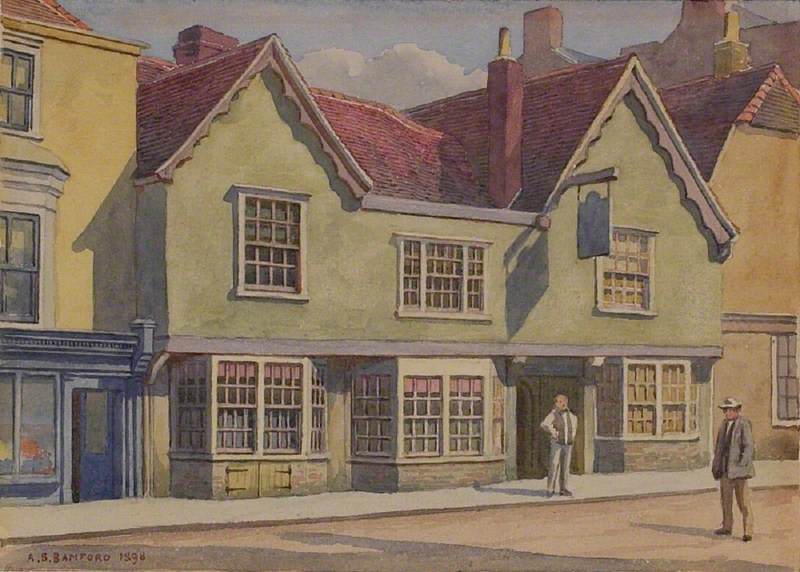

In July 1939, the trio of artists left for a painting holiday in the rural village of Leonard Stanley, near Stroud in Gloucestershire. Here they stayed at the 'White Hart Inn', which now has a plaque in honour of Spencer. They remained there after the outbreak of the Second World War. By October, the Slade had been evacuated to Oxford. George spent each Sunday to Wednesday in Oxford, and the affair between Stanley and Daphne blossomed. Daphne, as she pointed out to me, was considerably taller than Spencer, although he made them the same height in some of his 'Scrapbook' drawings. He started these drawings in Leonard Stanley, inspired by his purchase locally of children's scrapbooks. Largely autobiographical in character, he kept them for reference for the rest of his life, making a number of paintings from them. Daphne features largely in the first of the 'Scrapbooks', where she is seen, for instance, sitting on Spencer's lap while they put on their shoes, and cutting his nails. As Daphne informed me, Spencer had trouble cutting his nails, so she would seize hold of him and just say, 'come on, it's time'.

Fetching Shoes

1939–1943, pencil on paper, 40.6 x 28 cm by Stanley Spencer (1891–1959). Private collection

The Woolshop (1939) was the first picture to be derived from a 'Scrapbook' drawing. On Daphne's birthday, the

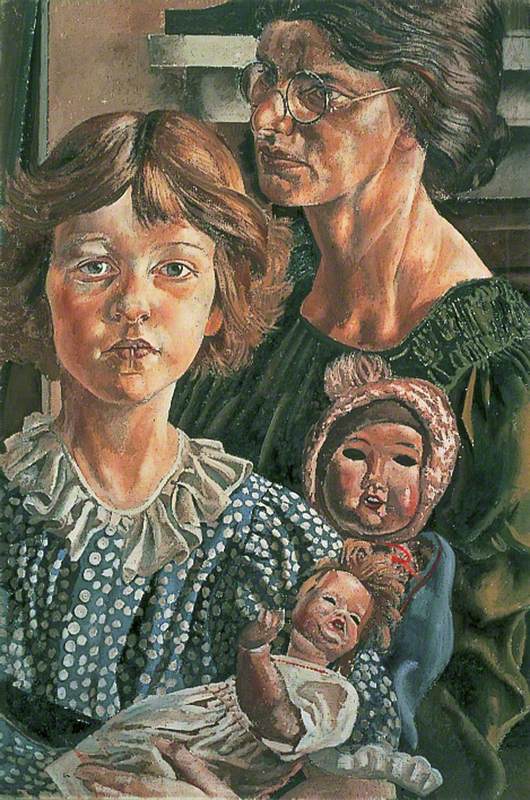

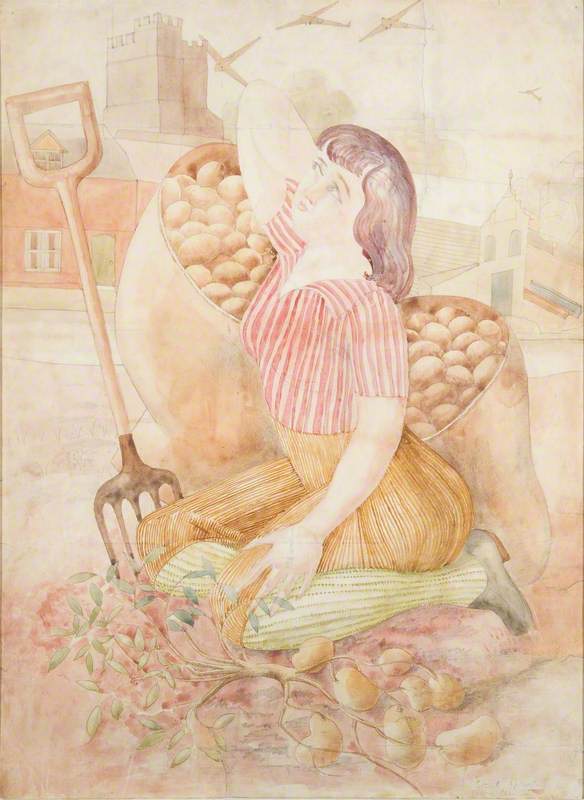

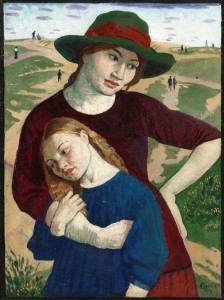

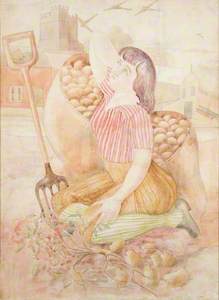

Village Life (1940), painted in Gloucestershire, shows an old couple and their grandchild witnessing 'the coming of God in the sky', while on the right, a sheepish Stanley Spencer is accompanied by the tall, commanding figure of Daphne and his first wife Hilda, who looks away. This is despite the fact that Hilda never visited him in Gloucestershire. Dig for Victory (1940) is a unique collaboration between Stanley Spencer and Daphne Charlton (who both signed the work). It was designed as a poster for the village hall in Leonard Stanley, in support of the government's campaign at a time of rationing to encourage the population to grow its own food.

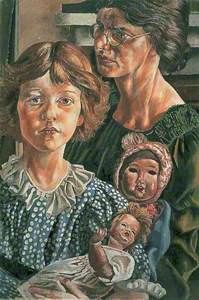

Over Easter 1940 the three artists temporarily returned to the Charlton's London home in Hampstead, where Spencer painted his striking portrait of Daphne. She wears a decorative blouse and a jaunty little black hat, with a pink rose and veil. She told me how she and Stanley had made an expedition to New Bond Street, where he purchased the fashionable hat for 3 guineas. In the 1970s, she was still demurring at the cost, saying that he could have obtained a perfectly good hat for 12/11d (less than a pound). Daphne also referred to Spencer's extravagant purchases of jewellery and clothes for Patricia Preece during the 1930s, which led him into financial difficulties, noting that he had never treated Hilda (or herself, except in this instance) in like manner.

Daphne's memories of sitting for this portrait remained vivid. She recalled posing daily for two to three weeks. She further told me that he deliberately reduced her to tears each day, to get some emotion into her face. She claimed that nobody else could cause her to cry: 'I don't know how, he had that power.' The sittings took place in the first-floor drawing room, where she is shown with a Chinese bowl behind her on the mantelpiece. On my visits to Daphne, the bowl was still there. (The hat, blouse and bowl – on loan from Burgh House & Hampstead Museum – are displayed together with the portrait for the first time in the current exhibition at the Stanley Spencer Gallery.) Spencer's friend and supporter, John Rothenstein, Director of the Tate Gallery, immediately bought the portrait for its collection. Spencer recalled an exhibition at the Tate of recent purchases: 'and my portrait of Daphne in a black hat was there as also was the Daphne herself in the hat getting quite a bit of “glory” out of it all'.

In his engagement book for 1947, Spencer recorded that on Christmas Eve he was in Hampstead with Daphne. On Christmas Day he was still in Hampstead, but with his former wife Hilda. Later that day he returned to Cookham to join his second wife Patricia at an evening party in the 'Bel and the Dragon' pub. In life, as in art, Spencer

Carolyn Leder, scholar on Stanley Spencer,

The exhibition 'An Artistic Affair: Stanley Spencer and Daphne Charlton' features many of the paintings and drawings arising from this affair. It runs until 1st October. A fully illustrated