In April 1815 Mount Tambora, a volcano in what is now Indonesia, erupted. It was the most powerful volcanic eruption in recorded history. The resulting effects on the international climate meant that the following year was known as 'the year without a summer'.

But what, may you ask, does this have to do with art, literature and the Gothic tradition? In fact it was one of several factors that helped create two classics of the literary genre.

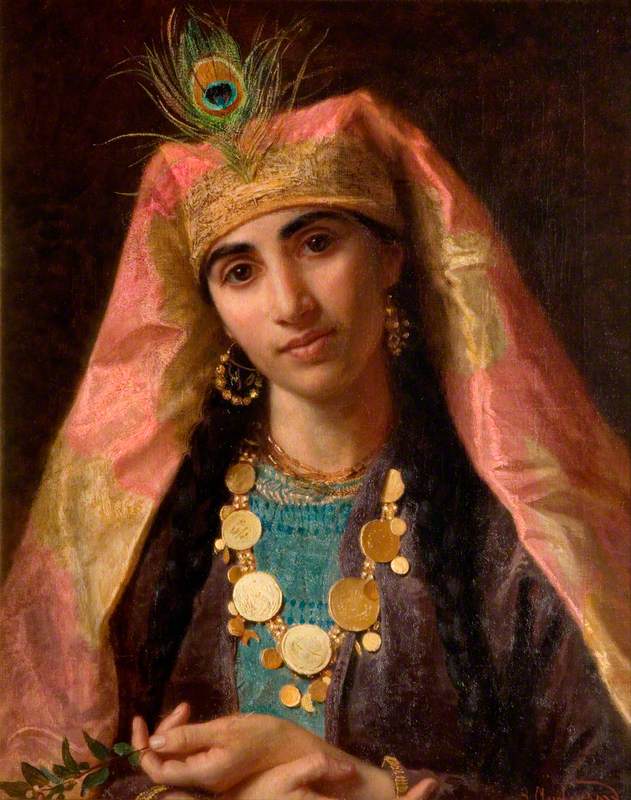

Let us begin our tale with a young Mary Godwin – her mother was women's rights advocate Mary Wollstonecraft, her father was philosopher and author William Godwin, and her future husband was to be the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley. Here she is much later in life in a famous portrait.

Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley

exhibited 1840

Richard Rothwell (1800–1868)

But Mary was more than a daughter and a wife – she was a woman with one of the most interesting literary ideas of her time. Mary Shelley – as we know her best today – came up with the story of Frankenstein.

The novel was to be brought to life through a meeting of a group of extraordinary people. In 1816 the eighteen-year-old Mary was travelling with Shelley, and they had rented a house on Lake Geneva. Not far from them, another poet, the famed Lord Byron, had rented a house known as the Villa Diodati. He had left Britain under a cloud of scandal, separating from his wife, having an affair and generally being in increasing debt.

Shelley and Byron had mutually admired each other's works, but had not met until this point. Byron was already a notable figure and his poetry was widely praised.

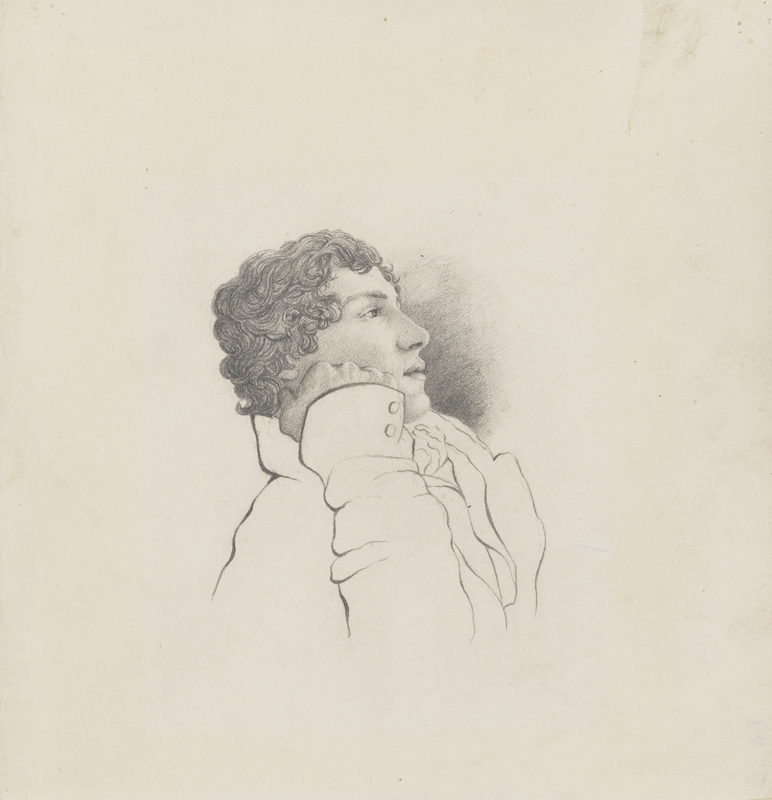

Shelley had had rather less success – he was perhaps more notorious for being sent down from Oxford (expelled) for writing about the necessity of atheism. (Much, much later, his college forgave this transgression and put up a statue to him.)

It was really decades after his death (he died aged 29 in a boating accident in 1822) that Shelley's fame began to grow. He held radical views for his time about atheism, free love, republicanism and even vegetarianism. It has been argued that his posthumous fame was also partly down to his wife – Mary had edited 1824 and 1839 editions of his poems to highlight his lyrical gifts and downplay his controversial ideas.

But back to Geneva and 1816. On his European sojourn, Byron had brought with him his personal physician, John William Polidori.

Polidori was himself just 20 at the time – he had studied at Edinburgh University from the age of 15 and received his degree as a doctor of medicine in August 1815, aged just 19. He had written a thesis on sleepwalking at university, possibly foreshadowing his fascination with the slightly spooky. But more of that shortly...

As his surname suggests, Polidori's father Gaetano was an Italian émigré who had moved to England in 1790. Among other pursuits, he had translated various works, including Horace Walpole's The Castle of Otranto, considered to be the first Gothic novel – so young John perhaps had the genre in his blood.

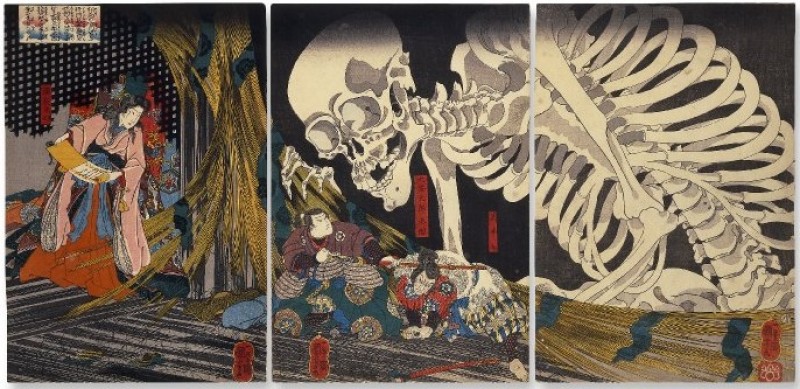

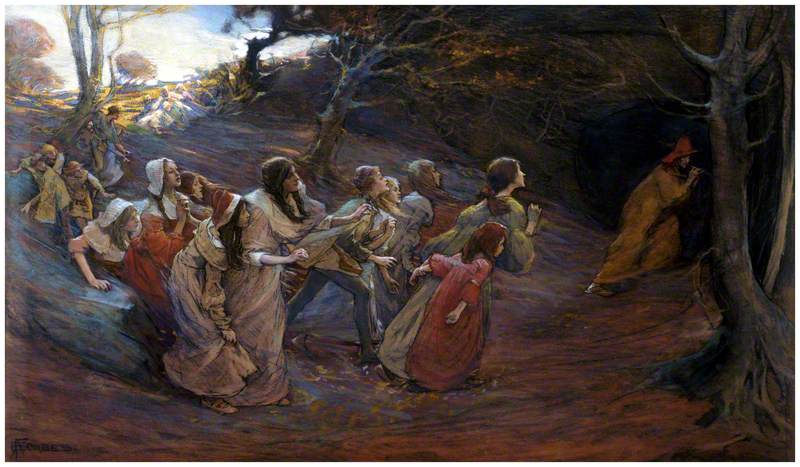

The Shelleys would come to stay at Byron's villa, and in the gloom of the evenings (thanks in part to the Mount Tambora eruption), they began reading ghosts stories to pass the time. They chose a collection of German tales translated into French, called Fantasmagoriana. As a result of this, Byron proposed a contest to see who could write the scariest story.

Shelley came up with nothing substantial, but Mary was inspired to write Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus – and thus won the contest.

Mary Shelley's Frankenstein is often called the first true work of science-fiction. On #WorldBookDay, see how one of the most important novels of the 19th century came to life. https://t.co/2CEhW9NRmf pic.twitter.com/EByzaFegkE

— The British Library (@britishlibrary) March 1, 2018

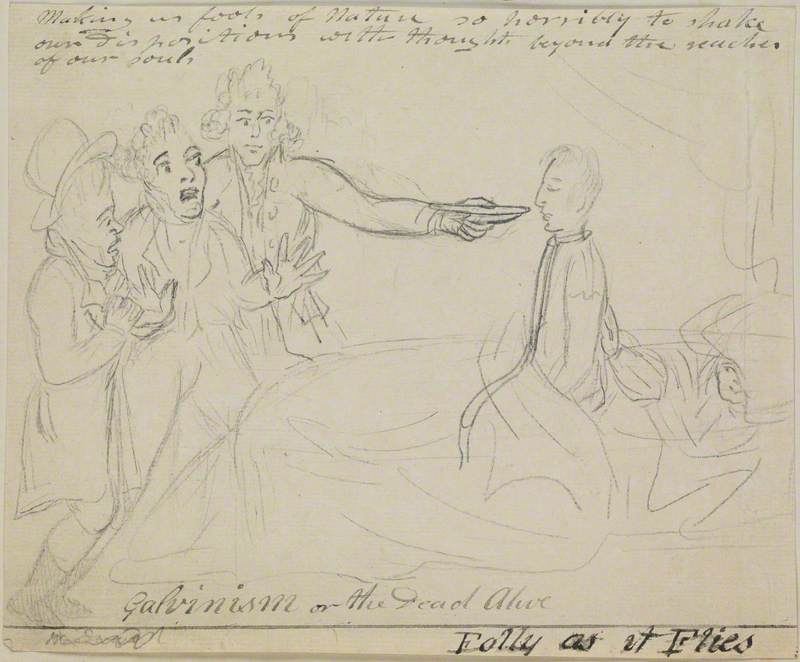

The mood of the time was a heady mix of the thrill of scientific discovery combined with the fear of its implications. There is evidence to suggest the Shelleys knew of experiments by Humphry Davy, Erasmus Darwin and Luigi Galvani – chemical, biological and electrical. These found their way in some form into the narrative of Victor Frankenstein and his creation of the Creature.

The Apparent Revival of a Dead Man by Galvanism

George Moutard Woodward (1765–1809)

The Creature itself – unlike most popular movie portrayals – is intelligent and articulate, and relates some of the story. The nature of humanity, the point of life and death, loss and guilt are all key themes. It is quite remarkable to remember that such an accomplished and wide-ranging tale was written by a teenager.

For his attempt at winning the contest, Byron wrote 'A Fragment', which Polidori then used as inspiration for his original work The Vampyre – the first novel about vampires in English, published around 80 years before Bram Stoker's now much more famous Dracula. (Incidentally, Dracula follows the epistolary format Mary Shelley employed in Frankenstein.)

Polidori's work had a more confused reception than that of Mary Shelley's book. It was published without his permission in 1819 in the New Monthly Magazine and was falsely attributed to Byron. This enraged both men, and it was only later that Polidori's name was inserted on the title page of the book, and Byron's removed. The attribution to Byron almost certainly helped its initial success, but the story of an aristocratic fiend (named Lord Ruthven) who preys among high society has become a standard trope in vampire fiction.

Sadly, Polidori did not live to see his work's profound influence on the genre. He was to die in 1821, likely at his own hand, poisoned by prussic acid, aged only 25. Although the coroner gave a verdict of death by natural causes, he was suffering from depression and weighed down by debt.

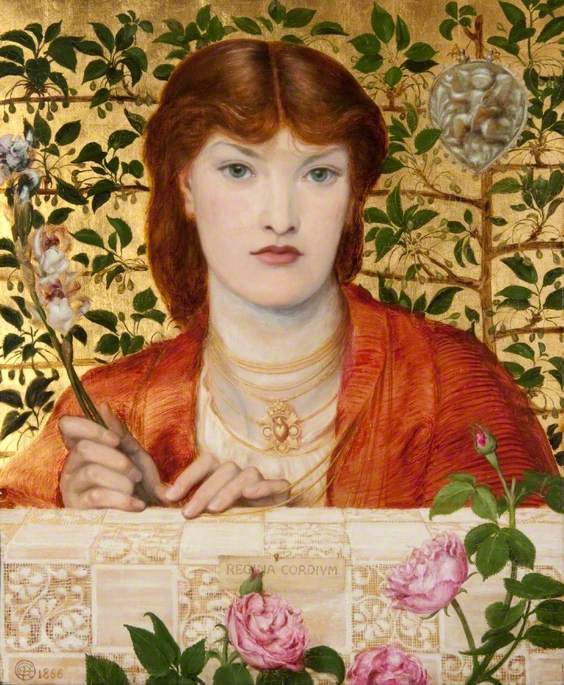

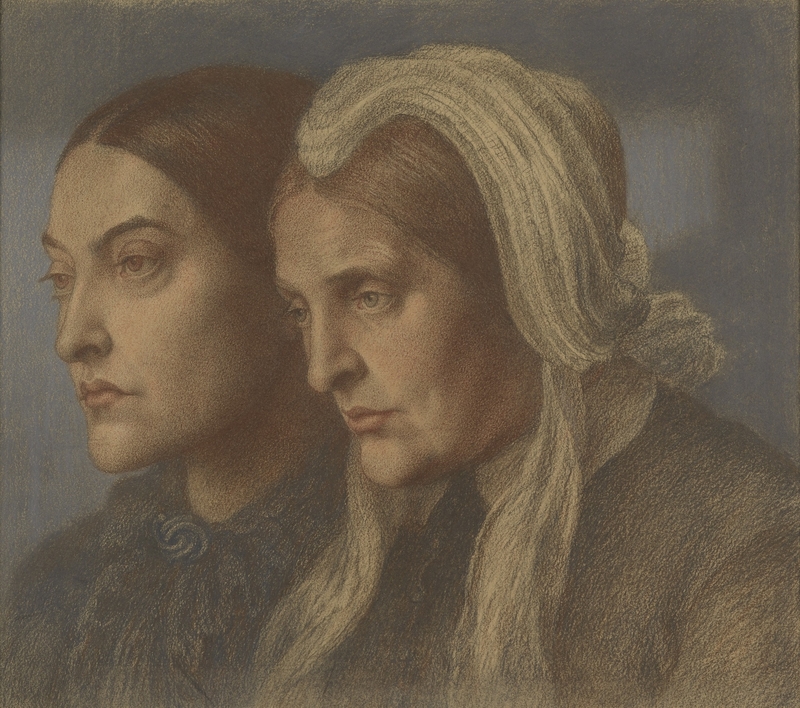

As an epilogue of sorts, his family had a remarkable connection to the art world. His sister Frances went on to marry another Italian, the politically exiled Gabriele Rossetti, and their children were the Pre-Raphaelite artist Dante Gabriel Rossetti, the critic William Michael Rossetti, the poet Christina Rossetti and the author (and nun) Maria Francesca Rossetti. This made Polidori their uncle, albeit posthumously.

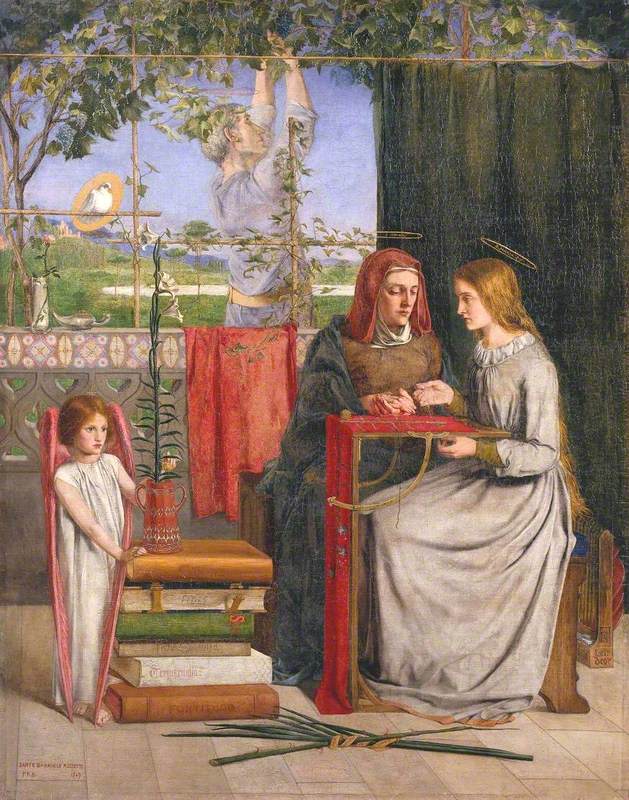

Dante Gabriel Rossetti used his own mother (Polidori's sister) in his works, notably as the model for Saint Anne (the Virgin Mary's mother) in his The Girlhood of Mary Virgin. Here's a double portrait of her and Dante's sister Christina.

Christina Rossetti and Frances Mary Lavinia Rossetti, née Polidori

1877

Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–1882)

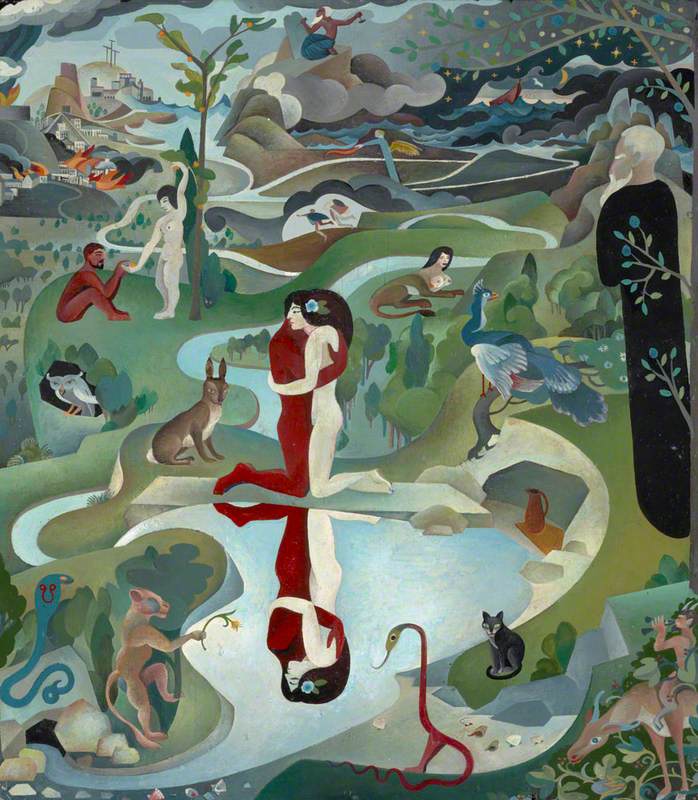

There are further links between Gothic/Romantic literature and the later Victorian art than just the Polidori-Rossetti family. The wider Romantic style encapsulated by Byron, Shelley and others such as Keats provided fertile ground from which the Pre-Raphaelites were keen to take inspiration. However, interestingly there are few – if any – paintings of the Gothic figures of Frankenstein and Lord Ruthven (the titular Vampyre). It would take the medium of film and television to truly realise the visual potential of these characters, although these twentieth-century versions may have little in common with the original source material.

As a final thought, without the seminal Gothic works created from that odd few days in Geneva in 1816, would Bram Stoker have written Dracula? Would the defining horror films of the twentieth century – adaptations of Frankenstein, vampire movies from Nosferatu to Interview With The Vampire, and the Hammer Horror classics – have been made at all? We can only imagine what would have been – but perhaps the true horror is to think that they would never have been made!

Andrew Shore, Head of Content at Art UK