Few artists in the north of Ireland have enjoyed careers as long and illustrious as the sculptor, painter and graphic designer Sophia Rosamond Praeger (1867–1954).

After training at Belfast's Government School of Art and the Slade School of Art in London in the 1880s and early 1890s, and following a brief stint at the Académie Julian in Paris, Praeger settled in the north of Ireland setting up her own studio first in Belfast and then in Holywood, the County Down coastal town where she had spent her childhood. She was the only daughter of the six children of a linen merchant, from a distinguished Dutch-German family of musicians, writers and entrepreneurs, who had moved to Belfast from The Hague in 1860. Praeger grew up in a liberal and cultured environment and her family thought little of her friendship with the local stonecutter John Lowry, in whose stonemason's yard she cut her first piece of marble as a teenager.

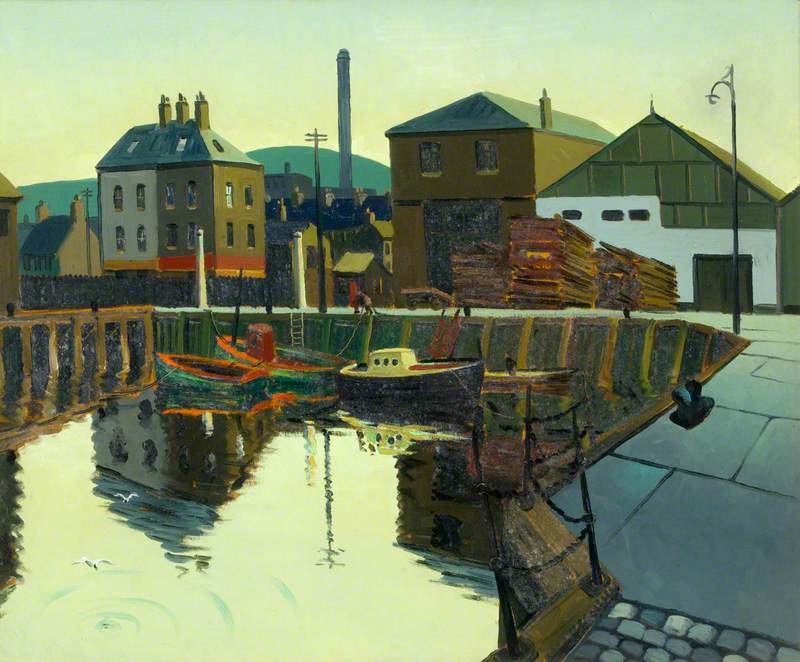

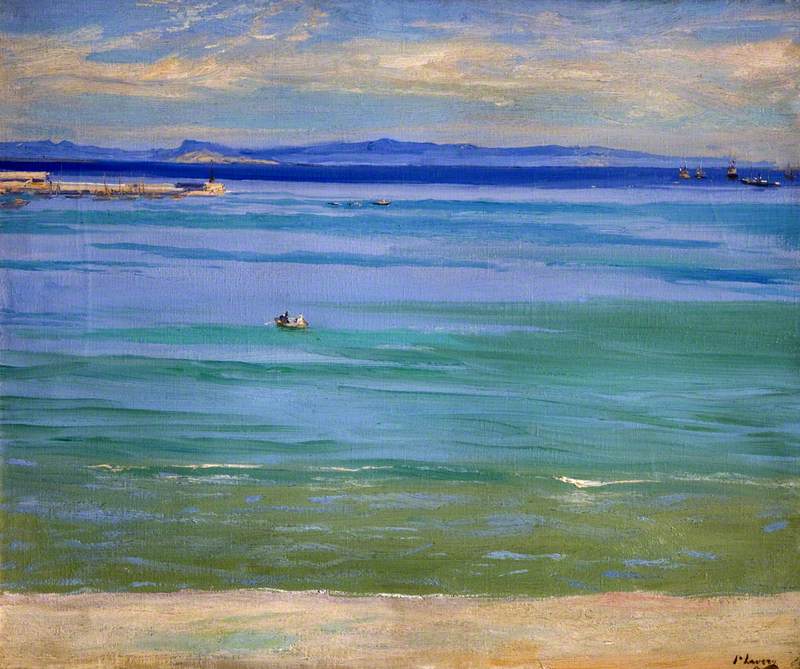

Exhibiting annually with the Belfast Art Society from the 1890s, she became a committee member in 1901 and first served as Vice President the following year. She also showed her work at the exhibitions of the Arts and Crafts Society of Ireland and in 1912 was a founder member of the Guild of Irish Art Workers. In 1927 she was elected an Honorary Royal Hibernian Academician just a couple of years after her friend Sarah Purser had been the first woman to be granted full membership. In 1931 Praeger was one of the twelve founder members of the Belfast Art Society's successor, the Ulster Academy of Arts. In 1941 she was elected President, nominated by John Lavery, and served until 1943 when she was appointed to the Arts Advisory Committee of the Council for Entertainment, Music and the Arts (forerunner of the Arts Council). She was the first woman to hold the presidency and was not succeeded by another woman artist until the appointment of Mercy Hunter in 1975.

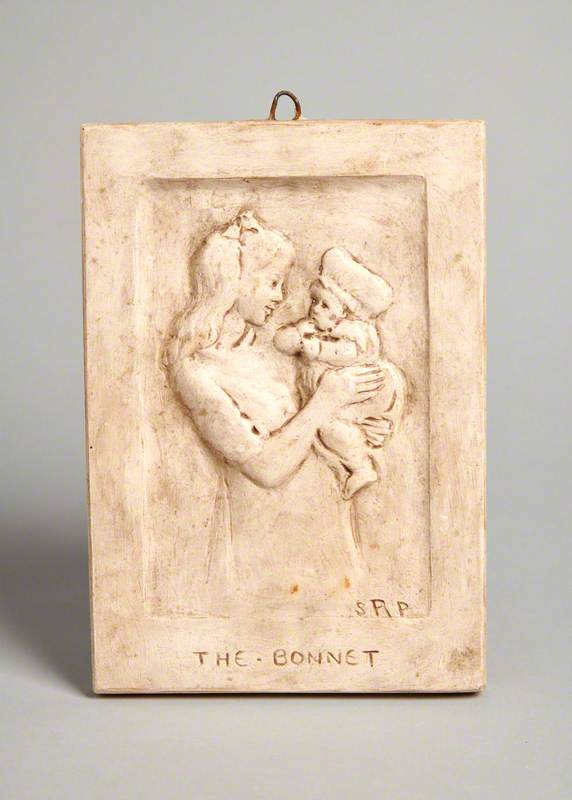

Praeger held two important solo shows in Belfast, in 1905 and 1912, at James Pollock's Gallery. Aside from these exhibitions, the most significant display of her work took place in 1924 in a joint exhibition with her younger contemporary Wilhelmina M. Geddes (1887–1955). In early November 1924, their joint exhibition opened at John Magee's Gallery in Belfast city centre. Of the exhibits, 46 were sculptures – designs for public memorials, statutes and low-relief panels, in bronze, marble, terracotta and plaster – by Praeger. Geddes contributed 33 prints, drawings, designs for stained glass and embroideries.

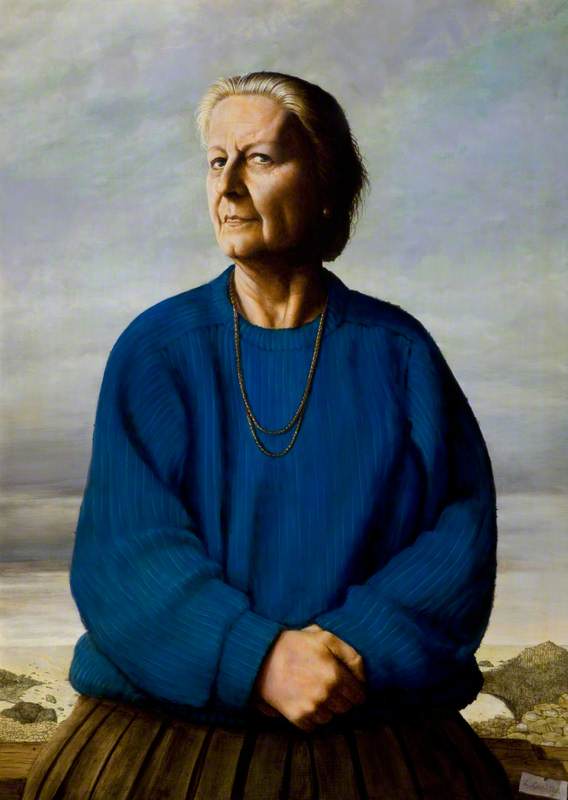

Portrait of S. R. Praeger

c.1924, original black & white drawing for linocut print by Wilhelmina Geddes (1887–1955)

Reviewers of the exhibition in the Belfast News-Letter commented on the feeling for beauty, the noble, archaic quality of the drawing and modelling in the work of both artists but also on the expressionism, undeniably modern in tone, most evident in works such as Geddes's deeply cut and boldly inked linocut portrait of Praeger.

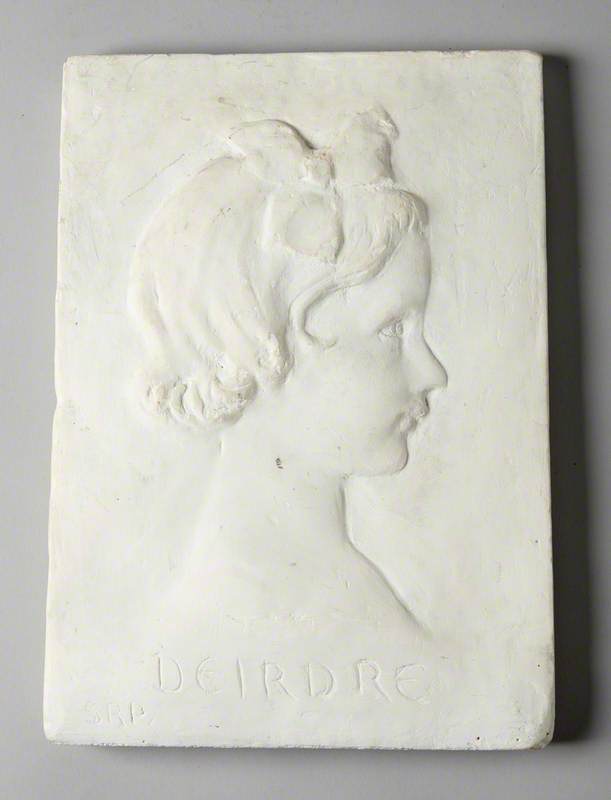

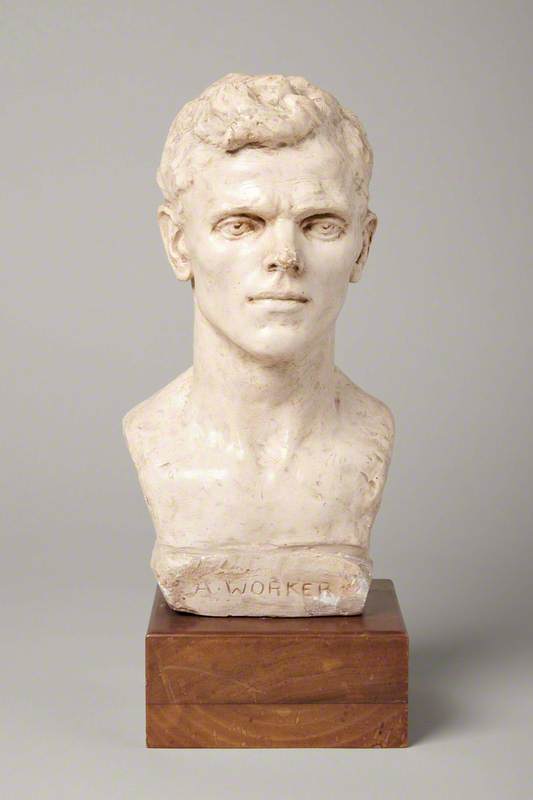

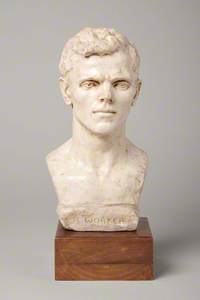

Praeger's earlier solo exhibitions, however, were much more successful in both critical and commercial terms. Reviewers praised her imagination as much as her skill, and early works such as Jane (A Child) or A Worker showed her abilities at working from life.

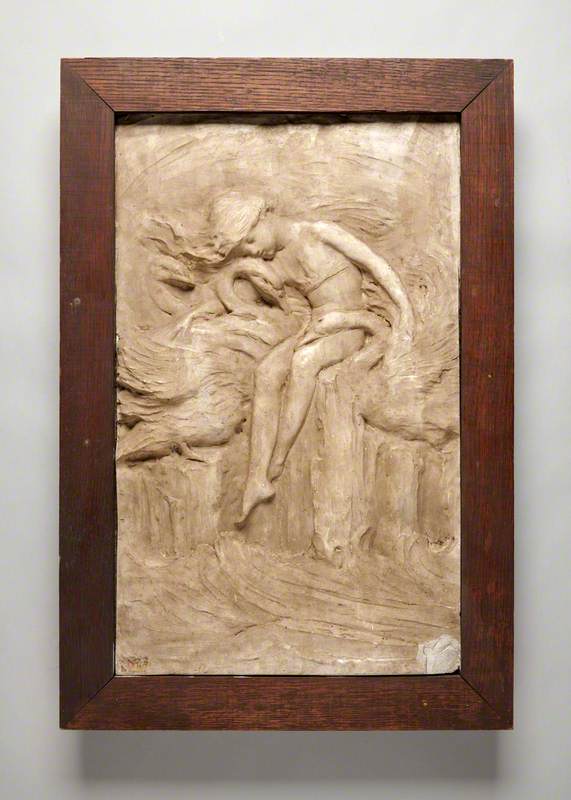

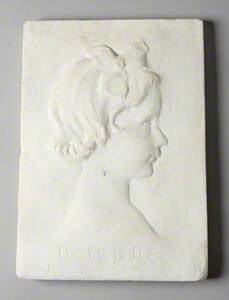

Much interest was also paid to her use of Irish mythological and folklore sources such as the story of the Children of Lir from which Praeger drew her Saint Fiachra, who was an Irish-born saint who appears in the Lir cycle, and Fionnuala, one of the four children of Aoibh and Lir in the legend.

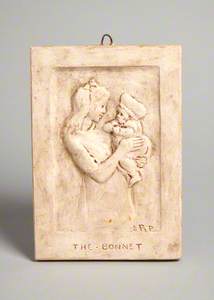

Attention was also drawn to the modern social imagery in Praeger's work, especially her depiction of working women, as in The Shawls.

By this time, however, an interest in the theme of childhood had earned Praeger the label of 'child-artist' and subsequently a reputation for producing work of less significance than many of her contemporaries – who might be described as a rather homogenous group of male landscape painters. Praeger's images of children were appealing in the marketplace, and there was also something in her work that interested the wider public, who saw through the disparagement – by critics – of subjects aligned to women's experiences as superficial and sentimental.

Take, for instance, a work such as Praeger's large marble The Fairy Fountain, which, in its portrayal of a sleeping child has some comparability to the more socially engaged practices of her immediate contemporaries, such as the Belfast photographer Alexander Robert Hogg who, like Praeger, produced work for Belfast Central Mission. The origins of the fountain are obscure and it may well have been produced for an organisation such as the Mission. We know that about the same time Praeger was carving her fountain, Hogg was photographing hundreds of destitute and deprived children for the Mission, creating a remarkable archive of human impoverishment in industrial cities such as Belfast. Praeger is known to have worked from photographs and may well have used Hogg's photographs of children as a source.

Childhood and modern, urban life may be important themes in Praeger's work but so too is nature. She was deeply interested in the natural world and was a committed and active environmentalist. She collaborated with her brother Robert Lloyd Praeger, the famous naturalist, on books (such as Open-Air Studies in Botany, 1897, and Weeds: Simple Lessons for Children, 1913) and provided illustrations for the journals he edited (The Irish Naturalist) and for his most famous scientific surveys (Lambay Island and its Surroundings, 1907). Praeger was also much in demand as an illustrator of children's books, working for various publishers, but eventually authoring and illustrating her own. She also produced a wide range of commercial illustrations for magazines and newspapers.

Praeger was captured in portraits by various contemporaries – from the photographers Alexander Hogg and Robert Welch to the painters William Conor and John Langtry-Lynas – but it is Geddes's dramatic linocut (above) that gives us a sense of Praeger as a brooding, complex figure. In the linocut, above Praeger's head in the right-hand corner, is an image of The Philosopher, a small marble statuette of an infant that Praeger made in 1908.

The Philosopher is still recognised as her best-known work and was reproduced in various media and in varied dimensions during her lifetime. The original marble (now in the Ulster Museum) was exhibited widely and was one of the few sculptures to represent Ireland at the 'Exposition d'art irlandais' held at the Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique in Brussels in 1930. Praeger not only made many versions of this herself, but she also licensed it for commercial reproduction. It is estimated that some 15,000 copies were made.

It is an image that has come to define her reputation as an artist and career as a sculptor. In many ways, it has and continues to obscure other important aspects of her life and work – such as her commitment to public art and her role as an activist, especially as an advocate of women's rights.

It is little acknowledged that Praeger ran perhaps the most successful sculpture studio in the north of Ireland from before Partition and up to after the Second World War. Her first major commission came in 1907 from the newly constituted Queen's University in Belfast, for a memorial to the Reverend Thomas Hamilton Memorial celebrating his newly appointed role as Vice-Chancellor. Commissions followed for memorials to civic and cultural figures, local families associated with business, politics or charity, and prominent women in education: these included Eliza and Isabella Riddel, Margaret Houston, Kathleen McNaught and Freda Smyth.

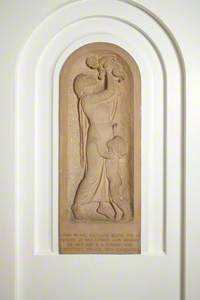

Memorial to Lieutenant Ernest G. Boas

1916

Sophia Rosamond Praeger (1867–1954)

Praeger also designed at least ten First World War memorials including those in churches in Holywood, on Belfast's Rosemary Street, Lisburn Road and Ellwood Avenue, at Campbell College School, Workman Clark's shipyard and Templemore Avenue Hospital – the latter is now in the Ulster Hospital. She also made sculpture for at least one free-standing war memorial, designed by the architect Richard Caulfield Orpen, in the centre of Omagh, County Tyrone.

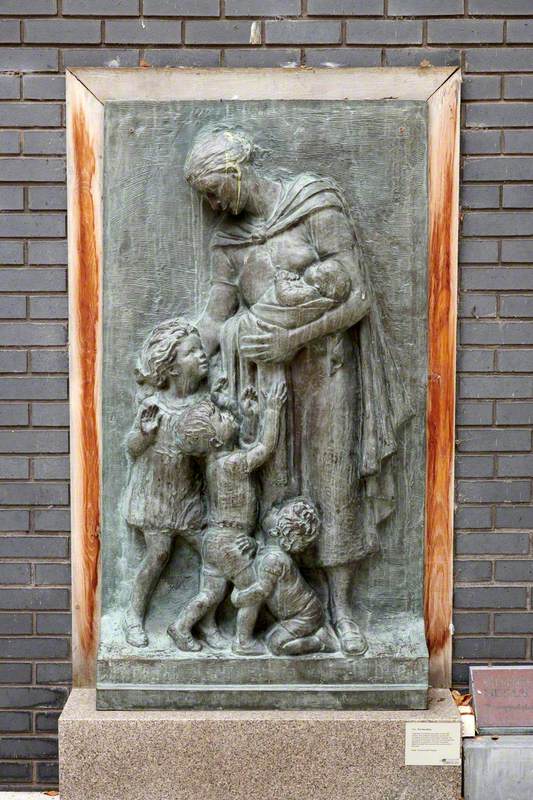

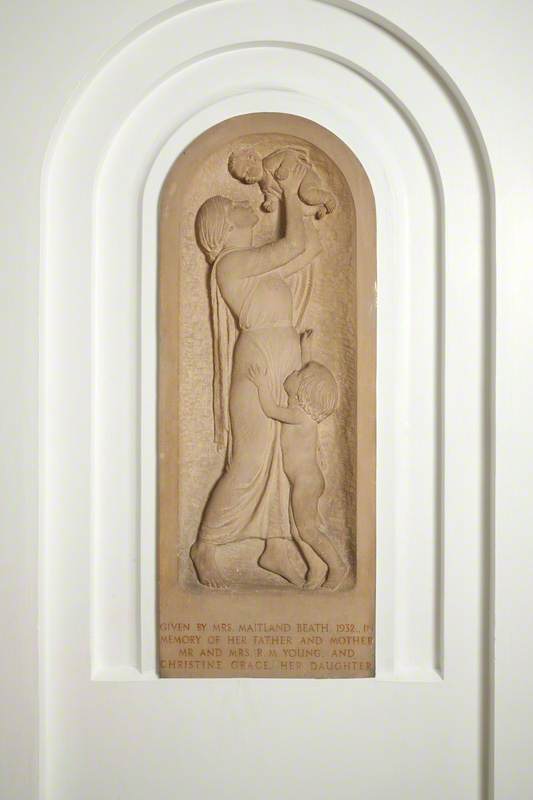

The Maitland Beath memorial at Belfast's Royal Victoria Hospital is perhaps one of Praeger's best public sculptures. The image of maternal joy was common in her work but exceptional in public memorials and the expressively cut Caen stone (a distinctive creamy-yellow French limestone) is a tour-de-force in direct carving. The memorial was installed at the entrance of the new maternity building of the hospital which also had roundels by Praeger on the building's façade. The building and scheme of sculptural decoration were unveiled by Lucy Baldwin, a campaigner for maternal care and wife of the Prime Minister, in October 1933.

Praeger was a tireless campaigner herself: aside from her career as an artist, she deserves to be remembered today as an activist. She was behind several schemes to raise funds for children's hospitals, the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children and the Ulster Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, and for numerous women's organisations from the Women's National Health Association to the Soroptimist Club (an international volunteer service to aid women).

Her activism is most apparent, however, in her prominent support of the suffragette campaigns. She produced posters, postcards and other material for the Suffrage Atelier in London as well as for the Irishwomen's Suffrage Federation in Belfast and Dublin. She raised funds, organised talks and made sculpture and other designs, such as toys (she wrote to Sarah Purser in 1915 of her 'doll factory'), to fundraise for the campaign and she contributed to the major 'Women's Exhibitions' held in London before the First World War.

Praeger was a lifelong advocate for women in the arts, lobbying collectors and curators to purchase and commission work by women artists. In the late 1920s, for example, she began a campaign to get the Belfast Museum and Art Gallery (now the Ulster Museum) to purchase work by Wilhelmina Geddes. In 1929, after Praeger's insistence, the Museum agreed to commission Geddes to make a stained-glass window illustrating the Children of Lir for their new building on Stranmillis Road. After Praeger wrote again to the Museum, they agreed to purchase a small domestic panel, Rhoda Opening the Door to Saint Peter. Geddes had been making panels for sale at exhibitions with limited success, even though they reveal her remarkable skill at working on a much more intimate scale than in the usual architectural setting of stained glass – evident in her Saint Joseph and the Angel panel which is now in the Stained Glass Museum, Ely Cathedral, Cambridgeshire.

The poet, art critic and museum curator John Hewitt recalled Praeger's support of Geddes: 'To the end there was a fire in her, for she wrote me in 1951 a graceful, but sharp, note pointing out that in a recently published survey of Ulster Art I had made no reference to her friend Wilhelmina Geddes, the stained glass worker – the greatest artist she claimed to have come out of Ulster.'

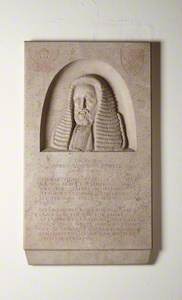

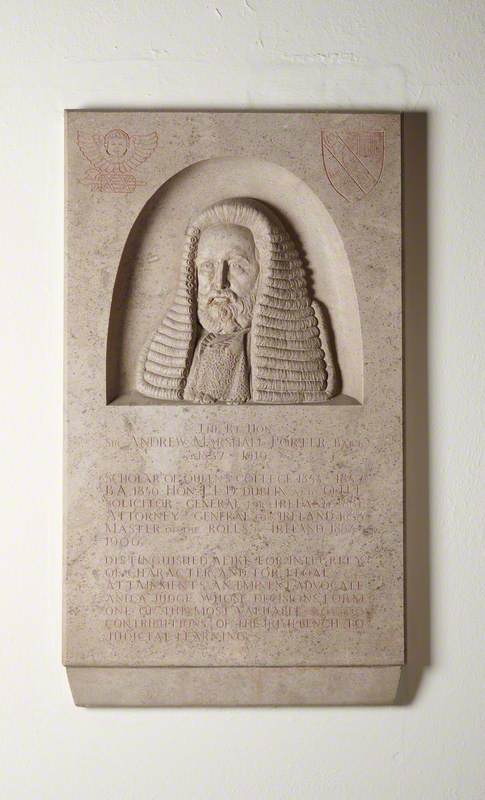

Sir Andrew Marshall Porter (1837–1919)

1948–1951

Sophia Rosamond Praeger (1867–1954)

Just before the outbreak of the Second World War, Praeger had attempted to secure for Geddes a further commission for a major window at Queen's University, following a recent bequest which included the commission for the Andrew Marshall Porter memorial that Praeger would complete in 1951 when she was 84. Sadly, Geddes reported to Queen's that she was too busy to 'undertake the design and construction of the stained glass for the window' as she was completing a major rose window for Ypres Cathedral in Belgium.

Geddes was the subject of a major biography published in 2015 (Nicola Gordon Bowe's Wilhelmina Geddes: Life and Work) but to date, there has been almost no serious academic writing on Praeger. She has been the subject of two retrospective exhibitions (in Queen's Hall, Holywood in 1975, and at Queen's University, Belfast, in 2007) but her work as an artist and activist today appears to be increasingly less remembered and little valued, even if substantial holdings survive across several museum collections.

Dr Joseph McBrinn, Reader in Art and Design History at Belfast School of Art, Ulster University