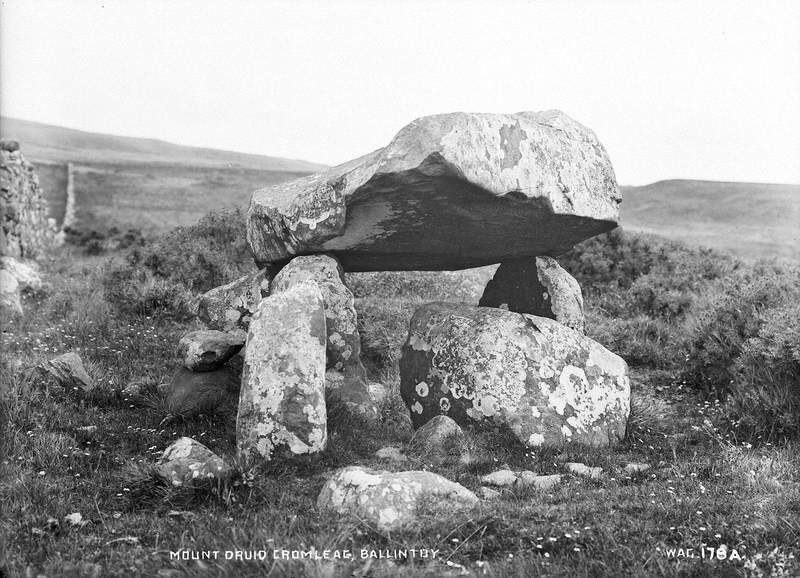

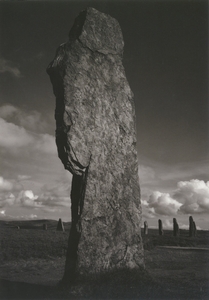

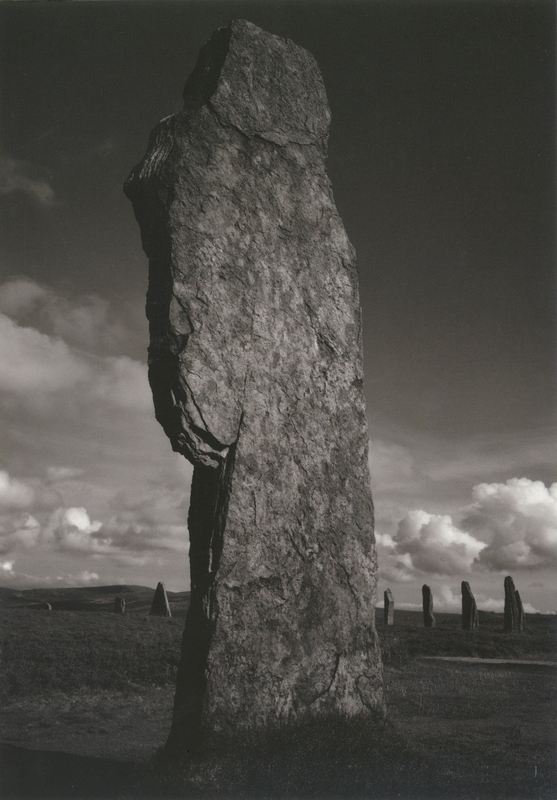

My interest in standing stones began on the bus. There is a single standing stone – a menhir – in one of the fields right next to my route, not too dissimilar to the image below, and the more I drove past it the more I wanted to know. There's not a huge amount of information about its history but it's thought to be part of a larger network of stones, now disconnected, across the county.

Standing Stone, Ring of Brodgar, Mainland, The Orkneys, Scotland, June 19, 1991

1991

Albert Watson (b.1942)

There are more than 1,000 stone circles scattered across the UK. Thought to be sites of battles between giants, petrified witches, druid temples and, more recently, enigmatic remnants of prehistoric cultures, these ancient monuments have continually fascinated archaeologists, artists and laymen such as myself. What can artworks tell us about our own connections to these circles and the landscapes they sit in?

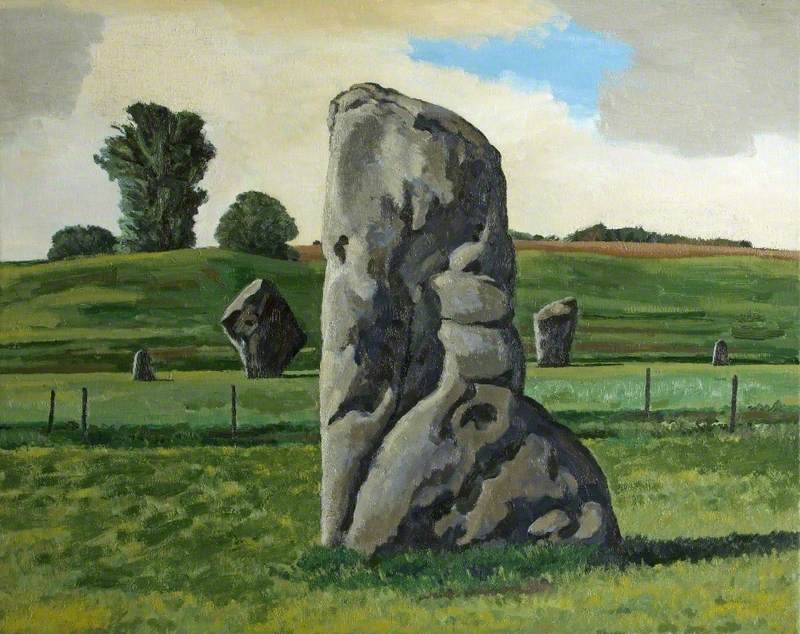

In the early 1970s, queer artist and filmmaker Derek Jarman (1942–1994) went on a pilgrimage to Avebury to see the largest stone circle in Britain. He filmed the standing stones using a Super-8 camera. Here, Jarman was participating in a long tradition of artists and antiquarians documenting these objects as they sat in the landscape – a tradition which has since continued.

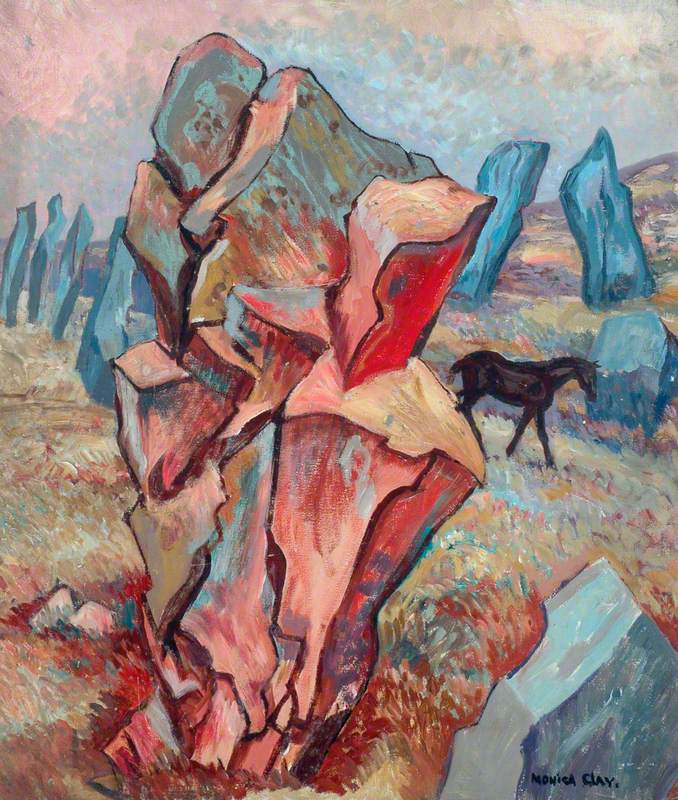

Standing Stones and Horse at Avebury

Monica Mary Clay (1912–1996)

We might think of circles such as Stonehenge and Avebury as quintessentially British, associating them with conservation and small-c conservativism – tea and scones in the countryside. Jarman's 10-minute film, A Journey to Avebury (1971), is anything but. It has an unsettling, eerie quality. Shots of the circle are intercut with other forms in the landscape – trees, roads, and cows all surely but sleepily encroach on the viewer.

This was not Jarman's first visit to a stone circle. His early landscape paintings depicted the 'megaliths and standing stones' of the Somerset he visited as a child. Jarman also features the Avebury stones in his series of landscape paintings from the 1970s.

Jarman's Avebury works emerged at the same time as the films and television that would come to be known as 'folk horror' – The Wicker Man, The Owl Service, Children of the Stones (which incidentally all feature standing stones). The exact definition of folk horror is still debated, but community relationships to the landscape and its stories are front and centre. These media explore the abuse of power that emerges through enacting and re-enacting ritual and myth.

They hold a tension between conservative Englishness and the queer and strange that chimes with Jarman's own film work.

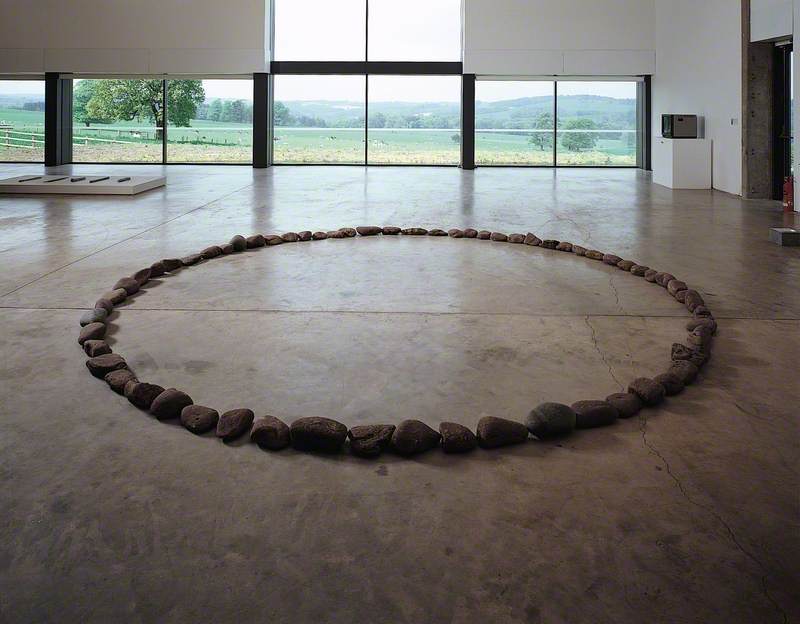

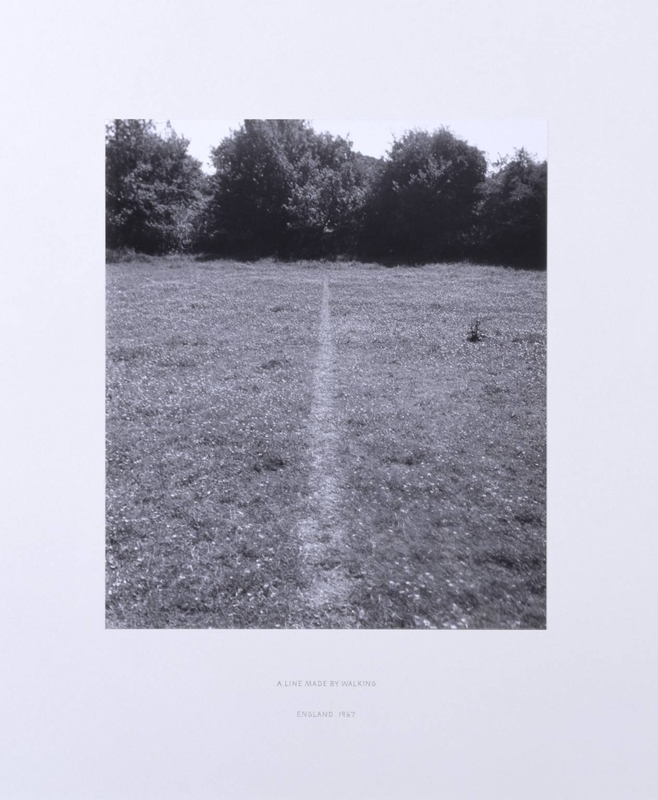

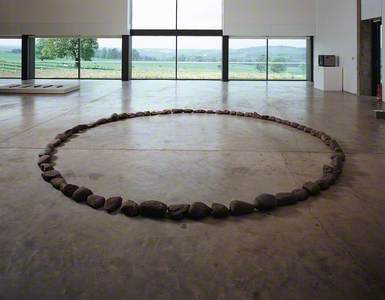

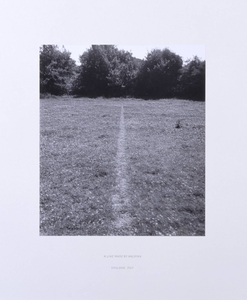

Stone circles appear again in Jarman's garden at Prospect Cottage in Dungeness. Photographs show miniature stone circles he built himself that call to mind the work of land artists such as Richard Long (b.1945). Land artists use natural materials already in the landscape, or make visible their movement in the landscape.

Speaking about land art, Long says: 'It is where my human characteristics meet the natural forces and patterns of the world.' This draws attention to ritual, and the physical sensations of being in a place. There is another sense of documenting here: trying to archive the actions and feelings in and of a place.

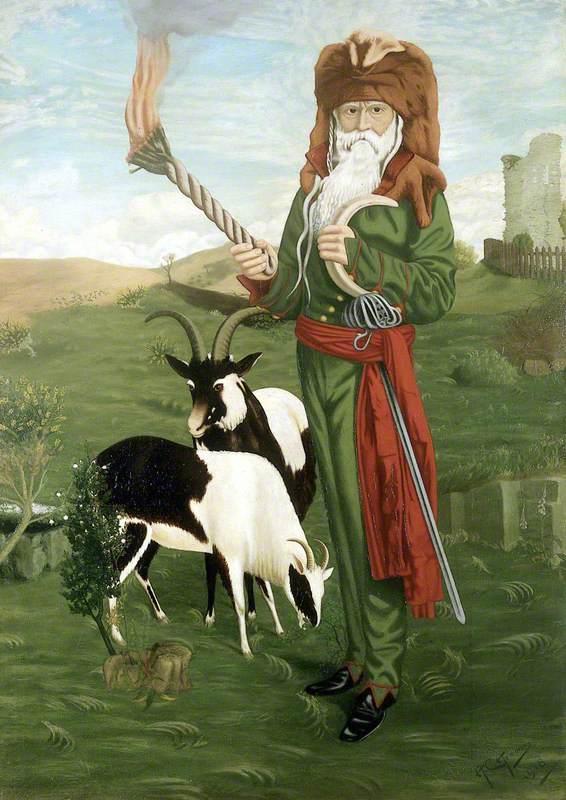

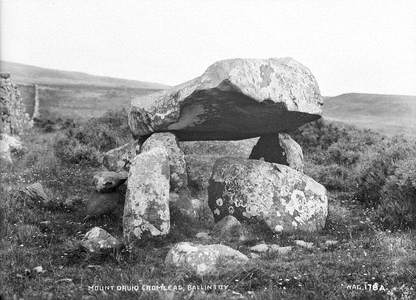

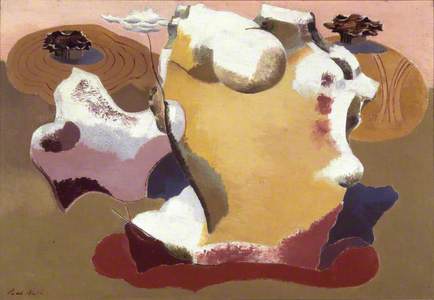

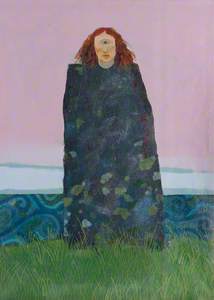

Ithell Colquhoun's (1906–1988) esoteric views and occultism were key to her artistic practice, as Amy Hale makes clear in her piece on the artist for Art UK. They were also central to her relationship with the ancient standing stones of Cornwall.

She wrote The Living Stones: Cornwall in 1957. Part-psychogeography, part-history, the book is the story of her desire to find a home, and a description of the landscape she found it in. She believed stone circles and monuments were 'repositories still of ancient power, the living stones.'

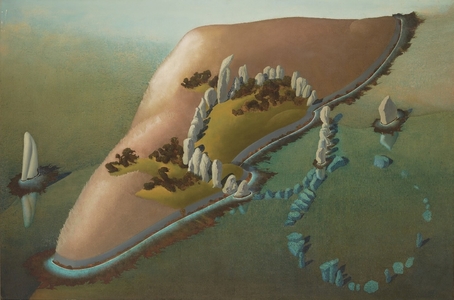

These beliefs echo in her paintings, particularly Landscape with Antiquities (1955) and La cathédrale engloutie (1950). These surreal paintings show the landscape as a network of energy points and exchanges, morphing into human-like forms.

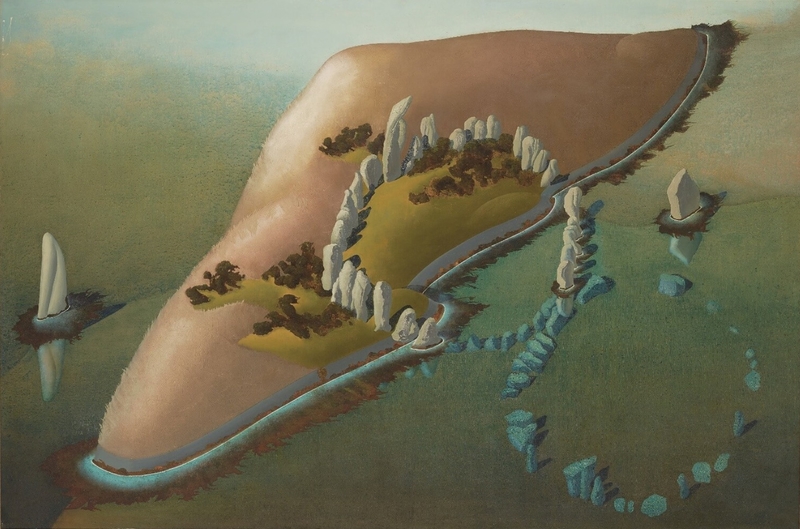

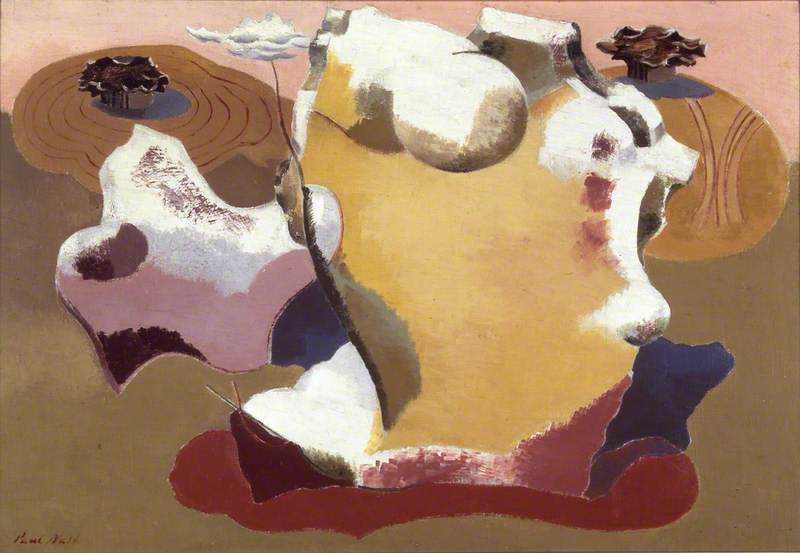

One of Colquhoun's fellow surrealists, Paul Nash (1889–1946), travelled to Avebury stone circle 40 years before Jarman in 1933. He was able to visit the circle before the stones were restored in the late 1930s and before access was restricted to prevent damage to them.

He later wrote that despite, or perhaps because of, their half-buried, overgrown state the stones 'were always wonderful and disquieting, and, as I saw them, I shall always remember them' and that 'to a great extent the primal magic of the stones' appearance was lost' with their later restoration.

His painting Druid Landscape (c.1938) is a provocative nudge to the archaeologists who were dryly set on disproving the beliefs of those such as Colquhoun. Druid Landscape and Landscape of the Megaliths (1934) share their anthropomorphic undulations and dream-like forms with Colquhoun.

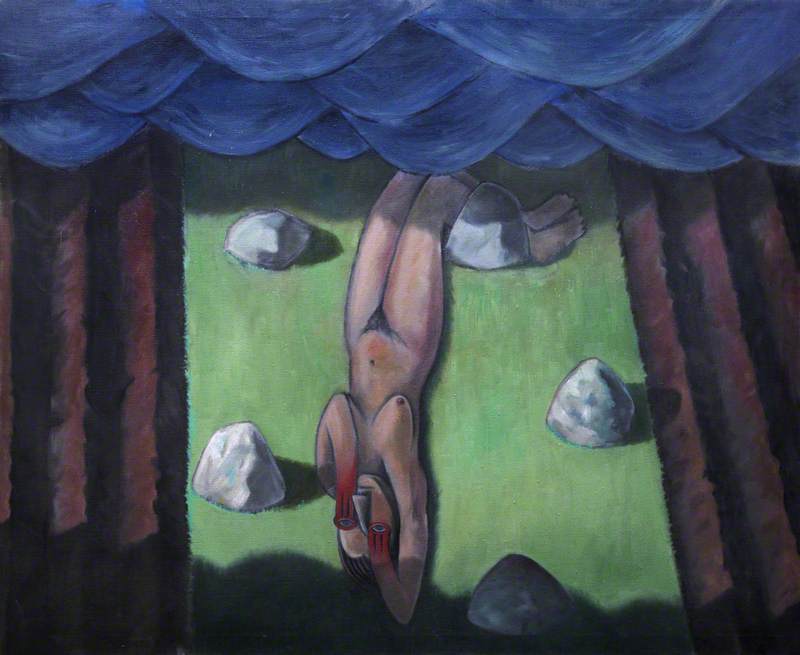

Also associated with the British surrealists, Marion Elizabeth Adnams' (1898–1955) later work Three Stones (1968), echoes this dreamy quality. There's a sense here that the three irregular forms occupy a world elsewhere.

Nash and Colquhoun also both make use of aerial perspectives in their work. Aerial views of the landscape were a new technology used by the archaeologists Nash was gently poking fun at.

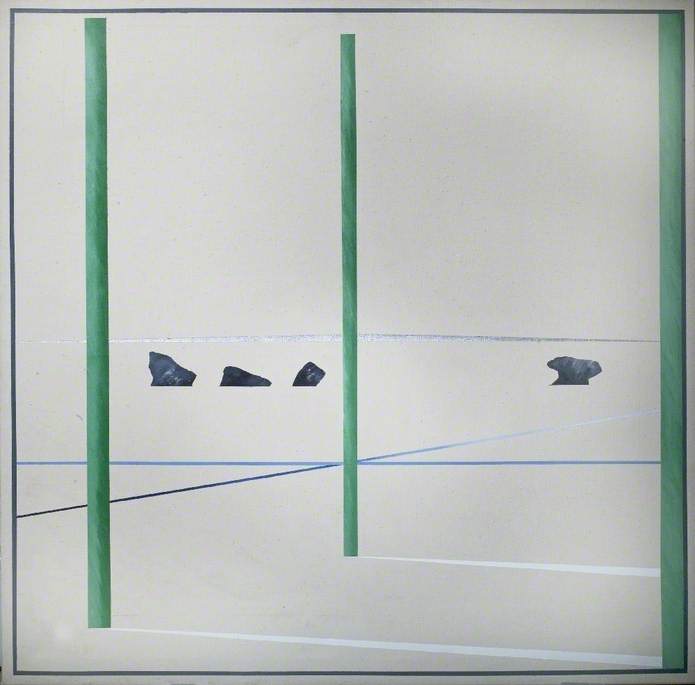

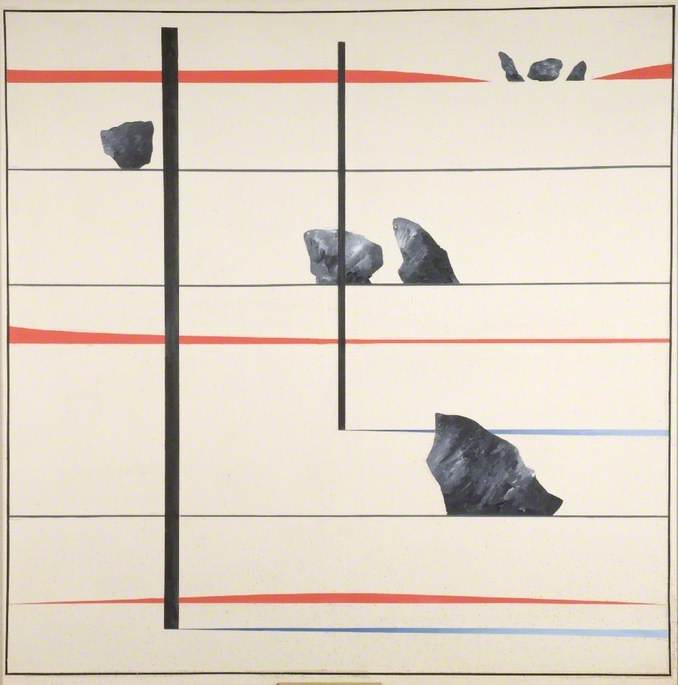

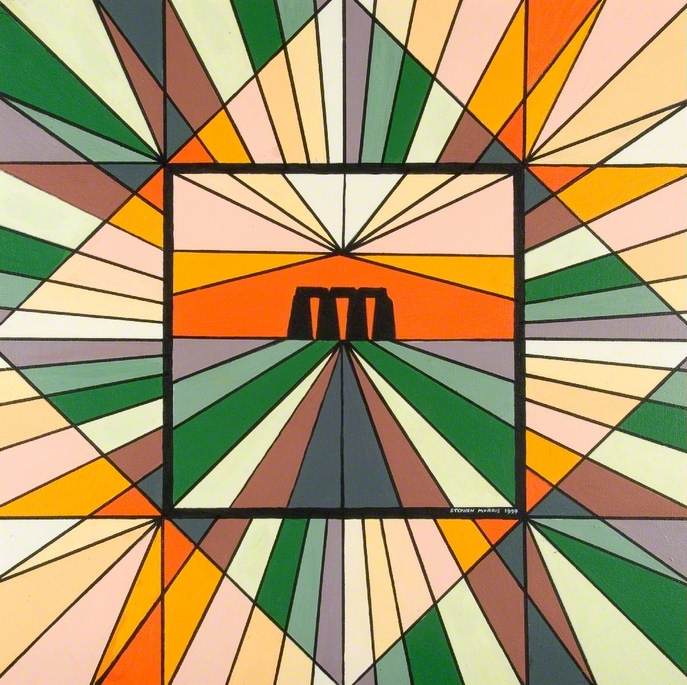

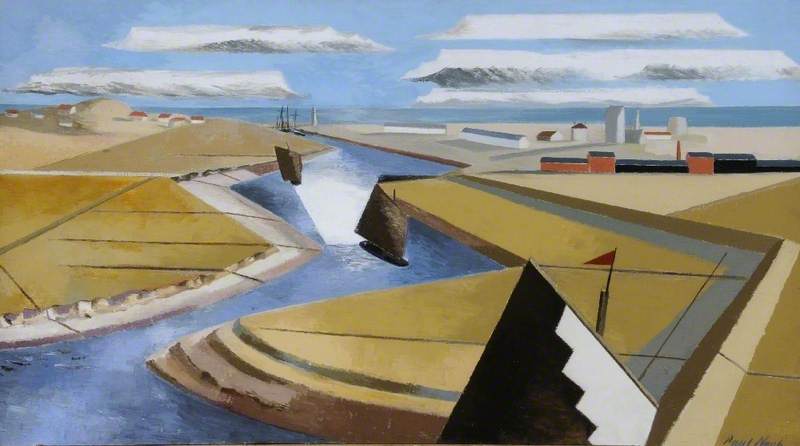

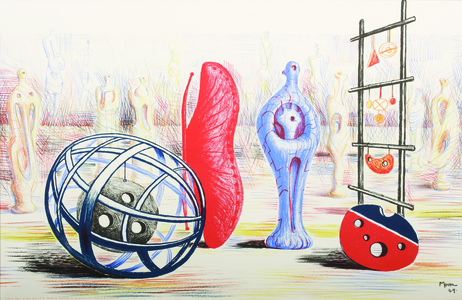

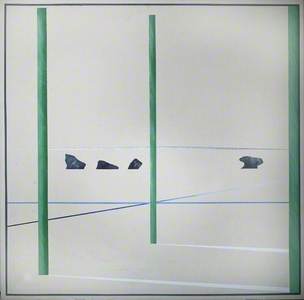

As Nash's Equivalents for the Megaliths (1935) shows, stone circles could also be abstracted into pure geometric shapes.

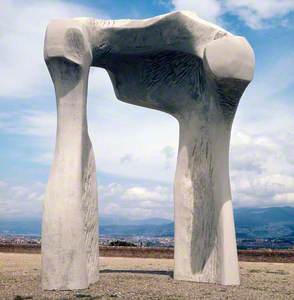

Constructivist sculptors were drawn to Stonehenge because of its formal, not necessarily spiritual, qualities. In 1937, three photographic series of Stonehenge appeared in Circle: International Survey of Constructivist Art. Two were taken by the art historian Carola Giedion-Welcker (1893–1979) and a third by Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius (1883–1969).

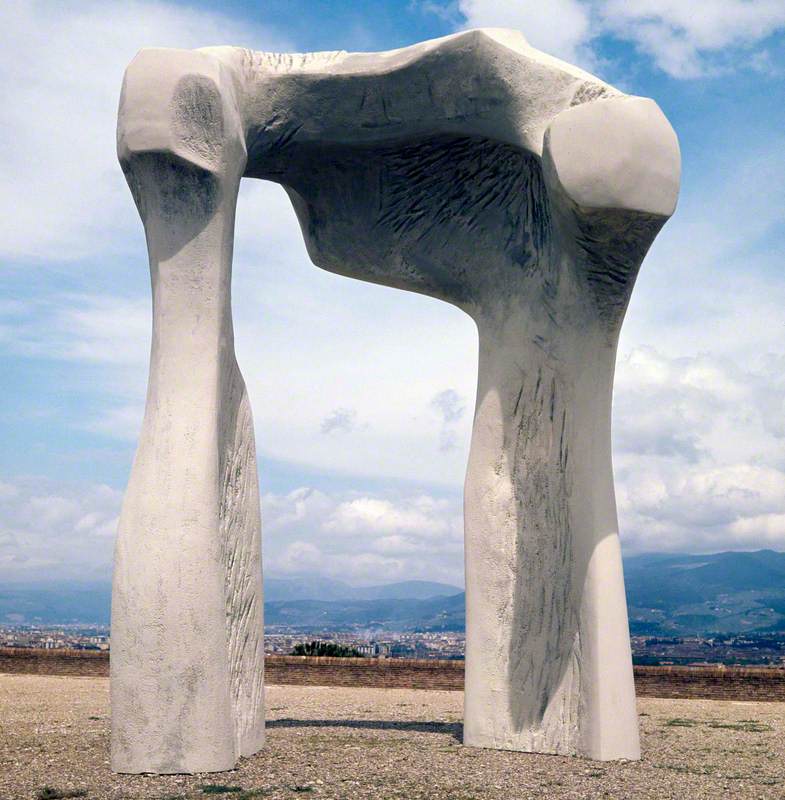

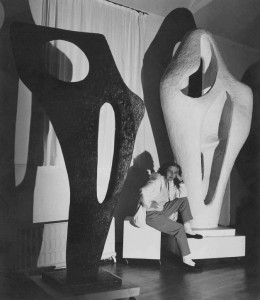

Sculptor Barbara Hepworth (1903–1975), tasked with creating the layout of the magazine, included one of the series next to her own article on form and gravity as essential qualities in sculpture. Many of her sculptures are megaliths or standing stones themselves, albeit on a smaller scale. Like Colquhoun, she was particularly inspired by the Cornish landscape.

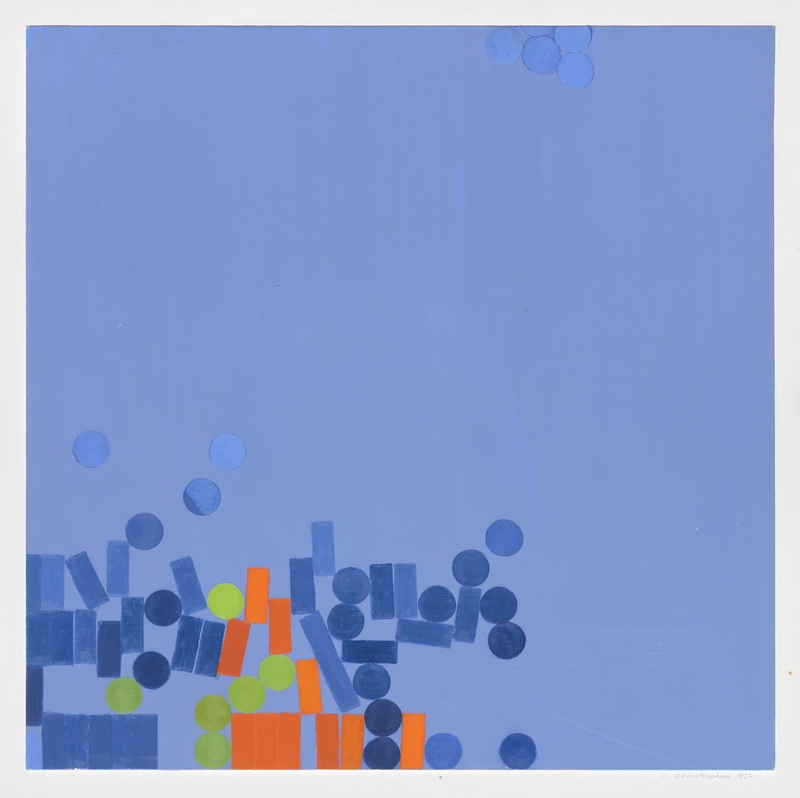

Another example of this abstraction can perhaps be seen in Wilhelmina Barns-Graham's (1912–2004) Rock Theme (St Just) (1953). Writing for Tate, critic and curator Rachel Smith suggests the geometric forms in the foreground of Rock Theme (St Just) could represent Ballowall Barrow (which I know is cheating – a barrow is a prehistoric stone feature, but not a stone circle).

In some ways it seems silly to suggest Barns-Graham's later circles and stones are referential – I start to wonder at what point am I reading stone circles into every geometric piece of work I see, because they're also geometric, but I do think you can trace the forms and textures of her relationship with stone landscapes in her later squares and circles.

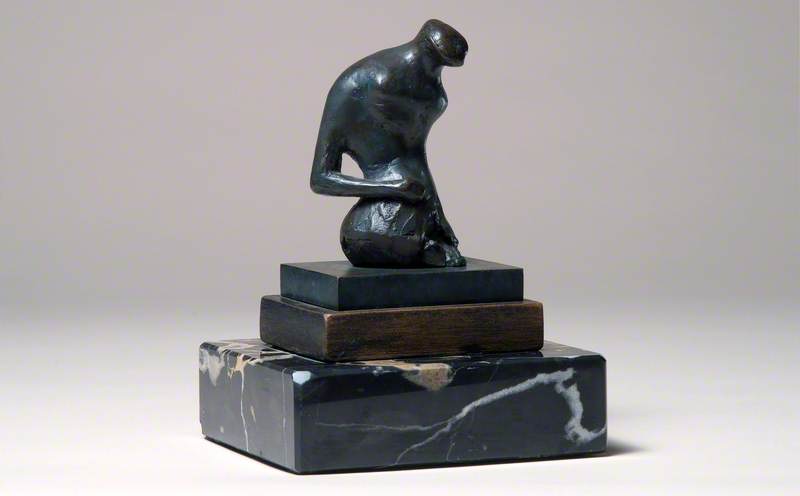

Finding the personal relationships artists have with standing stones has been my favourite part of writing this piece. The sculptor Henry Moore (1898–1986) is another artist who had an enduring fascination with a stone circle. He visited Stonehenge on a moonlit night in 1921 when it was still possible to walk right up to the stones and touch them.

'It was a clear evening I got to Stonehenge and saw it by Moonlight. I was alone and tremendously impressed. (Moonlight, as you know enlarges everything, and the mysterious depths and distances made it seem enormous). I went again the next morning, it was still very impressive, but that first moonlight visit remained for years my idea of Stonehenge.'

When he first moved to his garden at Perry Green he was delighted that his sculptures all arranged in his garden 'looked like a bit of Stonehenge'. Much like Barns-Graham and Hepworth, standing stones and stone circles are not always directly referenced, though once you know about Moore's longstanding relationship with Stonehenge you can see how it inflects his work.

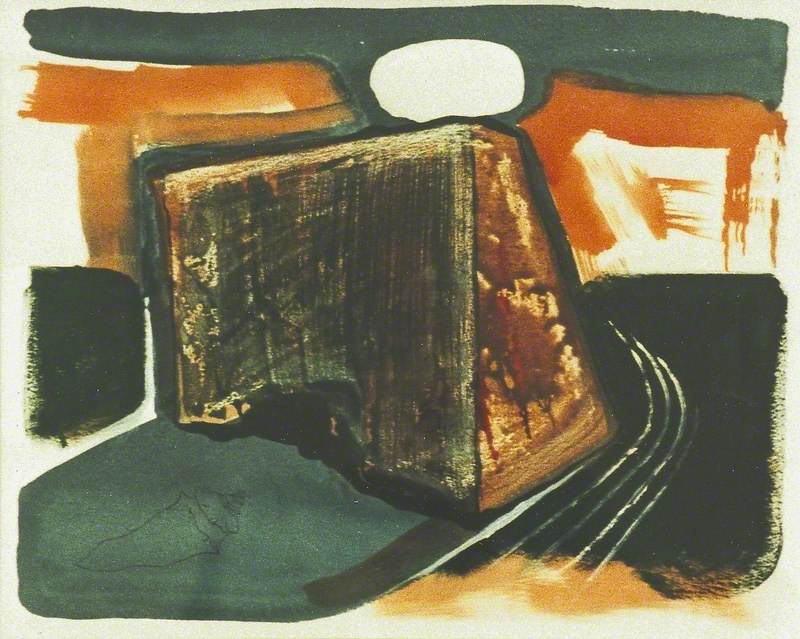

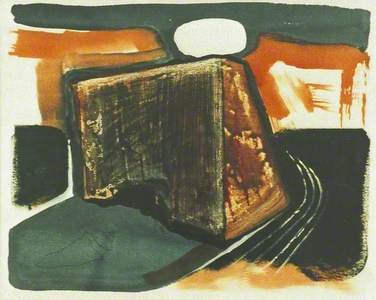

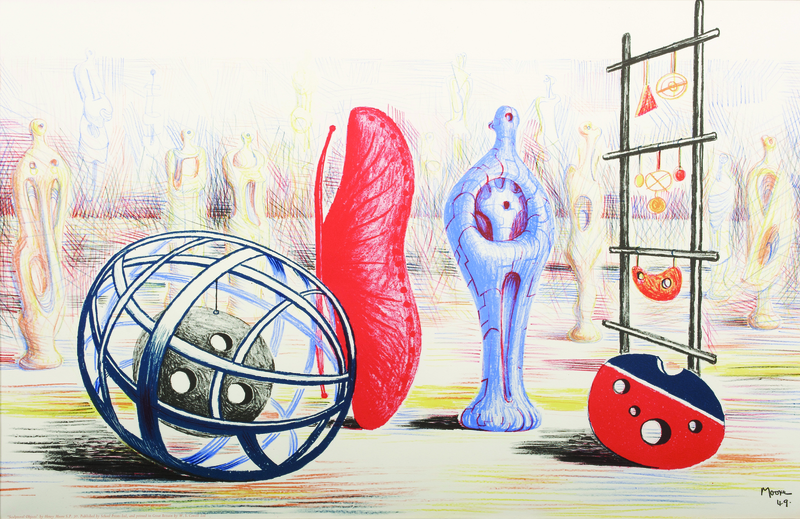

He does also reference it directly: he published a series of lithograph drawings of Stonehenge in 1973. One of his earlier lithographs, Sculptural Objects (1949), echoes Nash's Equivalents – instead of geometric forms occupying the same composition as a stone circle, it is made up of strange objects and forms.

Sculptural Objects

(from the School Prints Ltd series) 1949

Henry Moore (1898–1986)

So find your nearest stone circle or standing stone and get to know it. It doesn't have to be Stonehenge – it can, like mine, live a quiet life in a field of brassicas on the X7 bus route. As one visitor to the stones wrote in 2017: 'despite the cabbages, this was a lovely location and an atmospheric stone.'

Eleanor Affleck, writer and historian

This content was supported by Jerwood Foundation

Further reading

Alexandra Harris, Romantic Moderns: English Writers, Artists and the Imagination from Virginia Woolf to John Piper, Thames & Hudson, 2023

Derek Jarman, Dancing Ledge, Quartet Books, 1991

Robert Macfarlane, 'Walking in Unquiet Landscapes', Tate etc., 2019

Susan Owens, Spirit of Place: Artists, Writers and the British Landscape, Thames & Hudson, 2020

Adam Scovell, 'Perception of Landscape in A Journey to Avebury (1971) – Derek Jarman', Celluloid Wicker Man, 2014