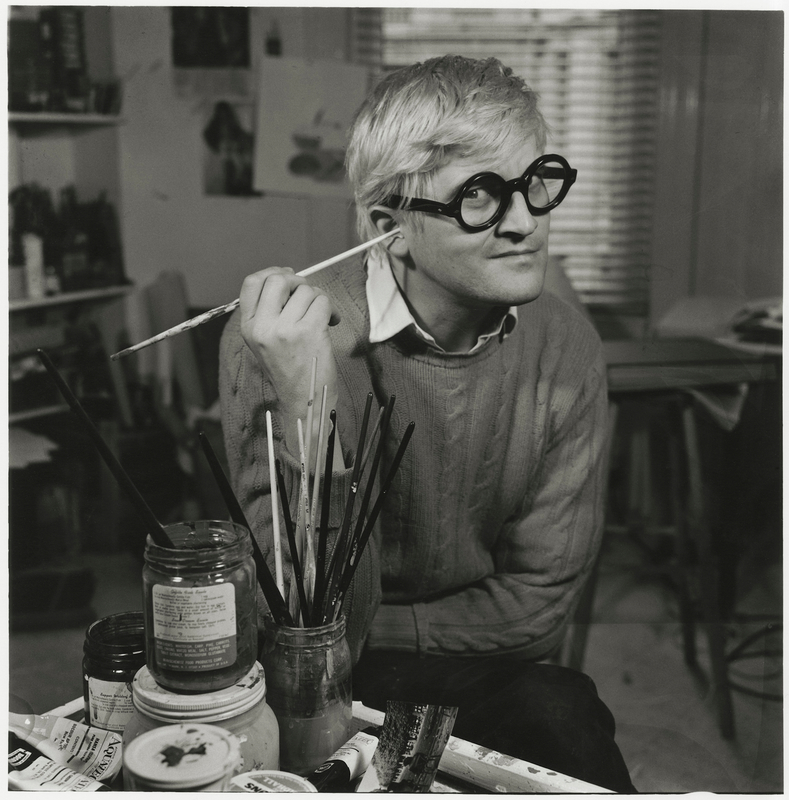

Sidney Nolan was born in Melbourne, Australia, on 22nd April 1917. This year marks the centenary of his birth. Edmund Capon, former Director of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, said that you cannot talk about Australian art without mentioning Sid Nolan. Considered one of Australia’s greatest artists, it is less well known that he permanently relocated to the UK in 1953 and remained here until his death in 1992.

Nolan is famous for painting subjects sourced from Australian history and many of them – such as Ned Kelly, Burke and Wills and Mrs Fraser – have achieved mythical status. Ned Kelly was a bushranger who divides opinion even today. He championed the rights of the working class but was embittered by his family’s constant encounters with the police. Three policemen were killed by the Kelly gang and Kelly was eventually tried

The controversial bushranger became Nolan’s leitmotif and he returned to the subject repeatedly throughout his career, both individually and in series of works. One could argue that Nolan’s depictions of Kelly, in his distinctive black helmet, with a hollow rectangular slot for his eyes, is the image most people associate with him. Nearly all Nolan’s repeated depictions of Kelly portray him in the armour and helmet that the bushranger made from ploughshares to protect himself and his gang. Yet, this belies the fact that Kelly only wore the armour at the final siege at Glenrowan where he was shot by police, yet captured alive and subsequently sentenced to death by hanging in 1880. Nolan painted a mythical subject that has become so important that his versions of them have themselves become mythical.

The figure of Kelly appealed to Nolan on multiple levels. Firstly, although the subject is rooted in Australian history it had strong resonances in British colonial history. Kelly was long regarded as the working-class Irish outlaw fighting what he perceived to be the oppressive British authorities. Nolan himself liked to make out he was

At the time he commenced the Kelly series Nolan was himself an outlaw. He had absconded from the Australian Army in 1944 and was living under a false name. He often said that his rendering of Kelly had an autobiographical element, which he did not want to disclose. This may be a response to the loss of his brother who drowned shortly before being decommissioned from the Australian army in the year before Nolan painted his first Kelly. The official government story, that he drowned in an accident while drunk, was never believed by the Nolan family. This profound loss haunted Nolan for the rest of his life.

The subject of Kelly undoubtedly appealed to Nolan on an artistic level. He had commenced his artistic journey as an abstract artist but ended up predominantly figurative. However, he did not follow the simplistic division between abstract versus figurative art that preoccupied the leading art critics of the day. In many

In November 1954, just after he settled in London, he created a unique painting, Death of a Poet. Nolan’s increasing importance in the British art world can be seen by the purchase of the work in 1957 by the Contemporary Art Society, which presented it to the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool. By then, both Tate and the Arts Council owned examples of the Kelly subject.

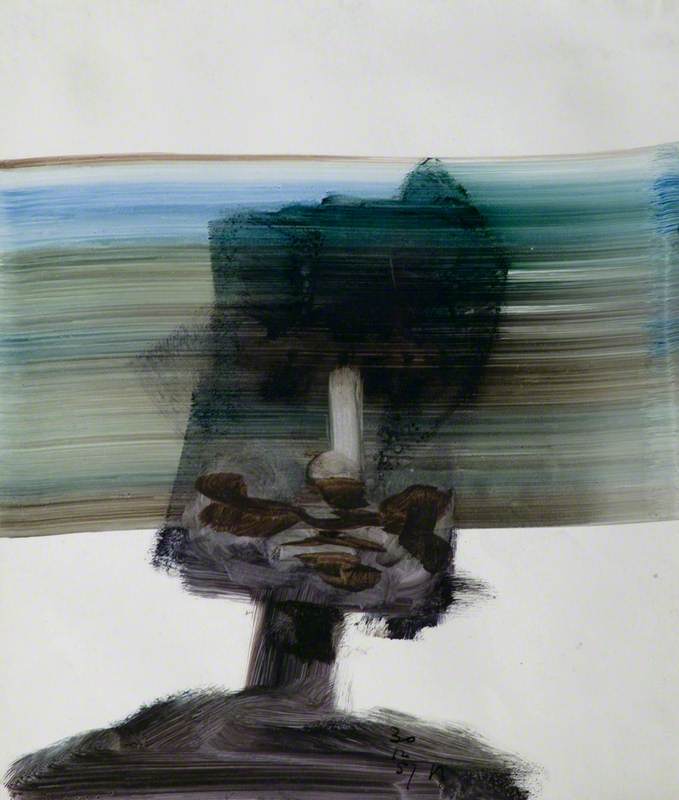

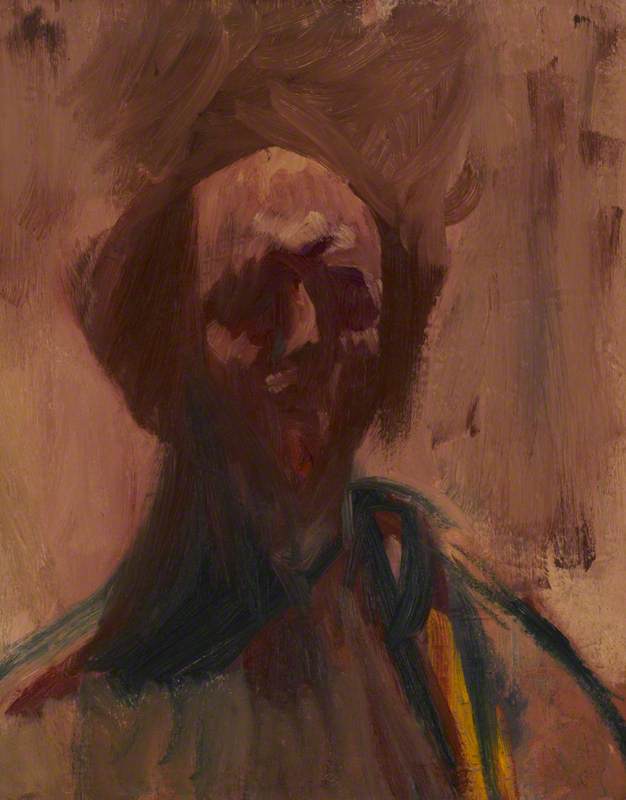

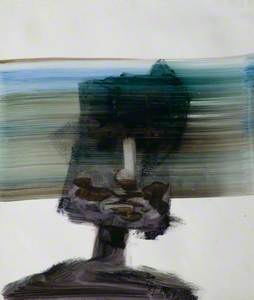

The sculptural mask floating in

Nolan was preoccupied with paintings of Kelly from 1955 to 1957. These works are pivotal to his development as a British artist because he alters his palette and the atmosphere of the often isolated figure. After he arrived in London Kelly takes on far more complexity and is used as a Universal figure often representing suffering and loss. David Sylvester, the art critic, reviewed Nolan’s 1955 series of Kelly paintings, which he concluded ‘have acquired breadth and luminousness and complete conviction’. He felt that Nolan must be considered one of the most important six artists in the world under 40.

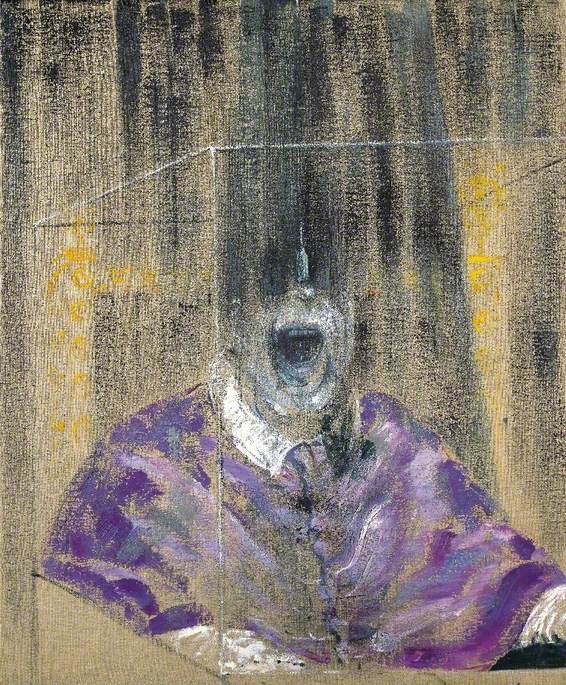

In 1956, Nolan painted a sublime version of Kelly, Kelly, Spring. The hue of the blue has radically changed from the bright azure of the Australian sky to a darker, colder, wintery blue of the Northern hemisphere. The bushranger stands gun aloft, the barrel uncomfortably positioned across the delicate portrayal of branches of cherry blossom. The helmeted figure’s features are divided in two; on the left, Nolan has depicted a sad, melancholy realistic face, like that of a lamentation, and this is contrasted with the right side which consists of red, blue and black horizontal abstract stripes. This is how Nolan subtly combined abstraction with figuration. The inspiration for this painting was the horrific news stories of the Hungarian Uprising, which had occurred that year and had deeply upset Nolan. Such was the success of Nolan’s Kelly that Robert Melville, the art critic, considered it as iconic in art as Giacometti’s standing man, Picasso’s Guernica and Francis Bacon’s Popes.

Nolan continued to depict Kelly until the end of his career. His close association with the subject is perfectly illustrated in his late, spray-painted portrait entitled

Rebecca Daniels, curator

The exhibition ‘Transferences: Sidney Nolan in Britain’, is on at Pallant House Gallery until 4th June 2017. It is part of a nationwide programme of events and exhibitions marking the centenary of the artist’s birth, organised by the Sidney Nolan Trust.