At the opening of the Venice Biennale, artist Shiraz Bayjoo presented a new performance and installation in collaboration with Nicolas Faubert and Siyabonga Mthembu. The work featured photographs and videos of plants that had been taken from Mauritius to London during the colonial era.

Installation view of 'Diaspora Pavilion 2' at the 2022 Venice Biennale

'I went back to the palm houses at Kew Gardens and thought wow, this is a living collection,' says the London-based artist. 'It's quite an extraordinary thing, a living collection, and one where some of the plants and trees were extracted during the height of slavery. They would have come on slave ships; they would have been witnesses to all that destruction and violence. Many of those plants can't easily be found in the wild again, so they are kind of existing in this silo. It was just the most overwhelming metaphor on so many levels.'

Installation view of 'Diaspora Pavilion 2' at the 2022 Venice Biennale

Bayjoo addresses a number of questions in his research-based practice. Who has the power to write, preserve and exhibit history? Which histories are hidden in plain sight, like those in the Kew Gardens palms? His work spans across painting, sculpture, photography, video and installation. He draws on personal and public archives, collaging archival materials together with contemporary imagery.

The archives he uses range from the geographical – such as maps from the islands of the southwest Indian Ocean – to the personal, including historical portraits of individuals. Some of the archival imagery almost seems comical until you realise how violent it is. Illustrations of colonial figures chasing birds with clubs and stuffing tortoises into bags demonstrate the colonisers' exploitation of nature and life. In drawing on these historical documents and images, Bayjoo creates space for discussing more contemporary issues about what colonialism and Empire left behind.

Coral Island

2021, decal and glaze on stoneware by Shiraz Bayjoo (b.1979)

Many of the archives that Bayjoo references were created in or about the islands of the Indian Ocean. While this reflects a biographical element of Bayjoo's work (the artist was born in Mauritius), his work speaks to larger concepts of what it means to be human. He is concerned with the universal struggle of people finding their own place and figuring out their position in relation to the rest of the world.

'I read the world coming from this space in the same way that you read the world coming from where you are,' says Bayjoo. 'So even though we have overlapping spaces that bring us together, we see these spaces from different perspectives. This gives us the opportunity to figure out what place means not only in terms of my relation to the world but for any of us.'

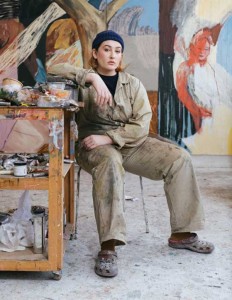

Shiraz Bayjoo

Bayjoo's use of the word relation is deliberate. He borrows the term from Édouard Glissant (1928–2011), a writer, poet and philosopher from Martinique who is regarded as one of the most important writers of the French-speaking Caribbean. Glissant argued that relationships on not centred on one single exchange, but are in reality based on multiple interactions across time and place. For Glissant, each person or identity is extended through its relationship with other people, identities, events and so on. The way that Bayjoo works across different mediums and with archival imagery that ranges across time reflects Glissant's theory of relation.

A closer look at Bayjoo's work reveals his references to a wide range of historical eras, from the 1590s to the present day. Sketches by Dutch sailors date back to the sixteenth and seventeen centuries and originally formed part of the De Bry collection of voyages, a series of volumes published in Germany documenting colonial travel across Africa, Asia and present-day Americas. There are photographic portraits from archives of the mid-nineteenth century. In some installations, these are paired with contemporary photographs and video that Bayjoo shoots himself.

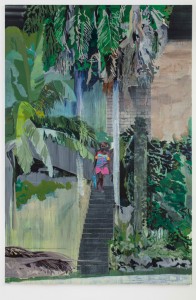

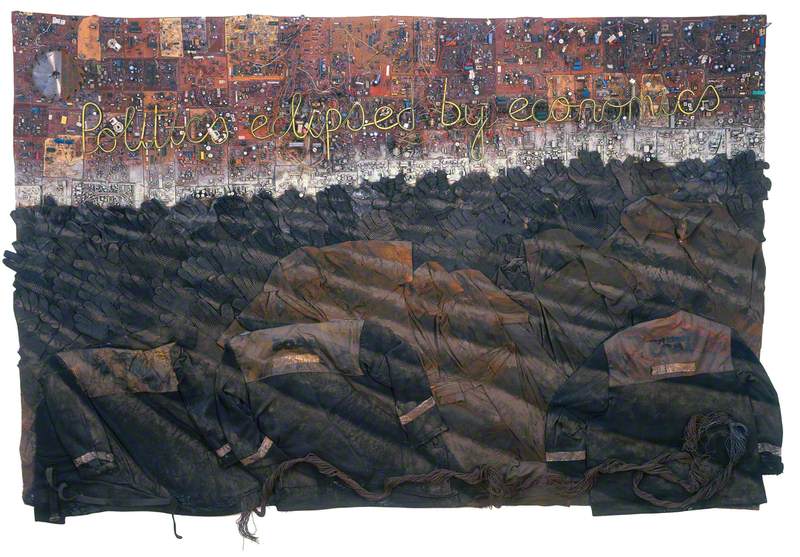

'Dan Sa Karo Kann (in those cane fields)' in 'We are History' at Somerset House

2022, installation by Shiraz Bayjoo (b.1979)

I asked Bayjoo if he sees history repeating itself in these images, but he points out that it is more complicated than that. Yes, there are patterns of repetition, but really it is about how part of history has influenced the next chapter. 'That's why it's interesting to bring things from different eras together, because you know that they have a relation,' says Bayjoo.

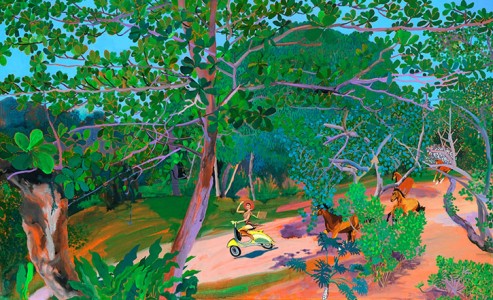

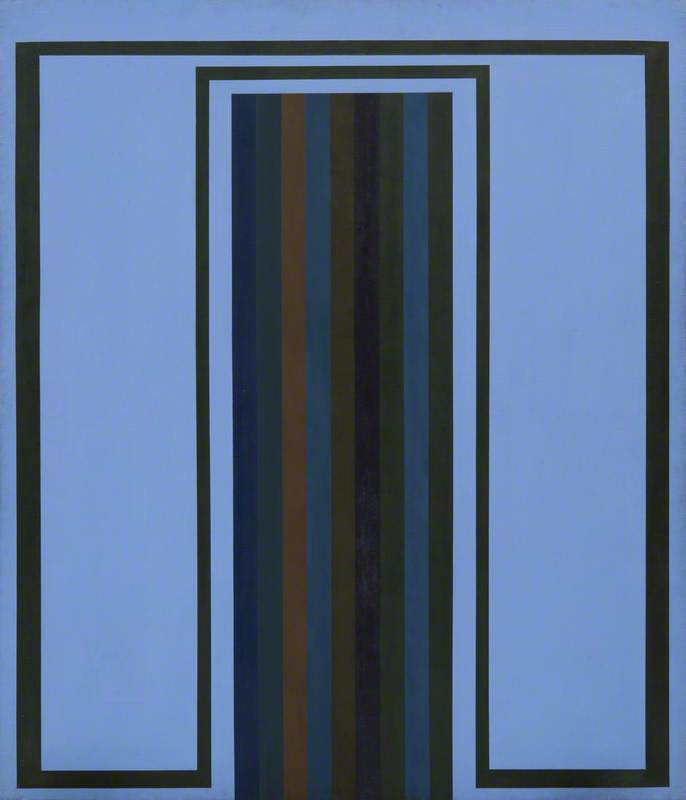

Installation view of 'Rivyer Nwar' at Copperfield, London

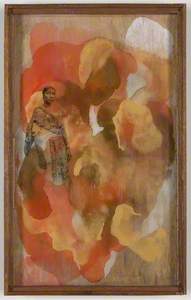

Bayjoo's series En Famille is another instance in which the artist brings together elements from different eras. Portraits from the mid-nineteenth century are overlaid onto wooden jewellery trays that once belonged to the artist's aunt, who was a very successful jeweller in Mauritius from the 1950s onwards.

The portraits are believed to be of servants who worked in the household of a wealthy, aristocratic 'Sugar Baron' family. A member of that family probably took the photographs, giving us a rare archive of a group of people who were so rarely documented. Bayjoo wants us to think about the possibilities of their lives – what were the loves and losses that took place. He focuses on the value of each life rather than on the violence that these people faced.

Bayjoo elevates them by putting their portraits in jewellery trays, but it is also a way of putting them to rest. He talks about laying them down in the trays as an act of remembrance and memorialisation. 'It's almost like letting ghosts rest,' he adds, 'which is why they're painted in a very particular way, slightly celebratory but also slightly invisible and fading away.'

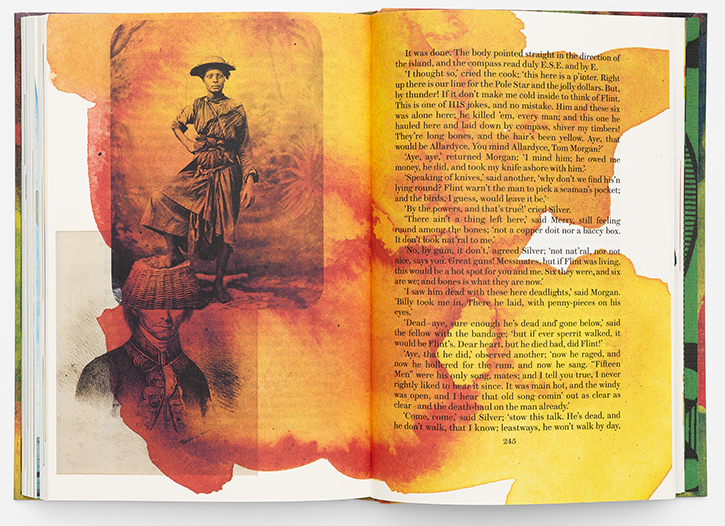

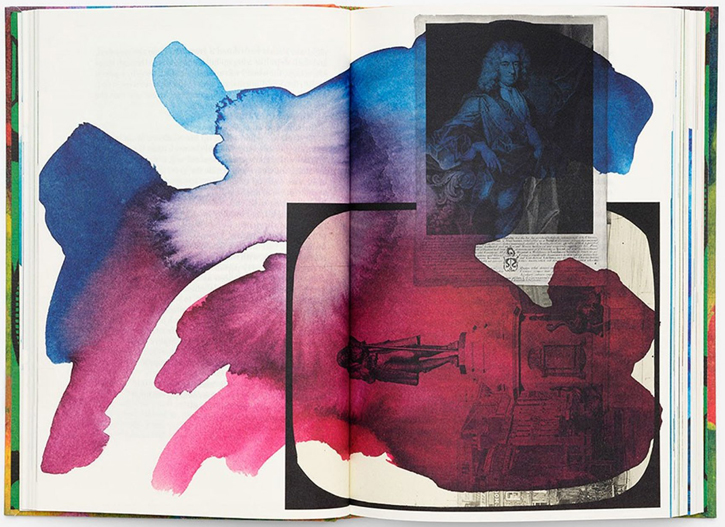

While En Famille challenges us to imagine the unrecorded stories of these very real people, some of Bayjoo's more recent work considers the stories we are often told of fictional people. For example, he recently released an artist book, published by Four Corners Books, in which he illustrates Robert Louis Stevenson's Treasure Island.

Bayjoo's visual interpretation of the book places Stevenson's tale in the context of eighteenth-century colonial Caribbean histories and relates it to wider global histories of enslavement and colonial violence. When the storyline takes the characters to Bristol, for instance, Bayjoo adds an archival image of Edward Colston's statue, overpainted with a deep pink-red stain of colour. Bayjoo turns the photograph on its side in reference to the June 2020 toppling of the statue. In this way, Stevenson's 1883 pirate novel is given a new layer of meaning.

Bayjoo also considers stories of piracy, this time within the context of Madagascar, in his work Searching for Libertalia. The work is currently on view at Glynn Vivian Art Gallery in a joint exhibition with Australian Wiradjuri artist Brook Andrew. Searching for Libertalia is inspired by A General History of the Pyrates, the book by Captain Charles Johnson (possibly a pen name for Daniel Defoe) that also inspired Stevenson's Treasure Island.

Searching for Libertalia clip on Vimeo.

Bayjoo's installation brings this fictional story together with historical narratives of slave trading by the French East India Company and with the history of Madagascar's fight for independence from France. The work focuses attention on more recent liberation and anti-colonial movements across the continent of Africa.

In Searching for Libertalia and in much of Bayjoo's work, the past helps us to think more critically about our contemporary global world. We gain a better understanding of how we have arrived where we are politically and economically through researching the past and exploring the web of relations that history holds.

Julia DeFabo, Art UK's Social Media Manager

'Shiraz Bayjoo and Brook Andrew, Ngaay – Konesans' is on view at Glynn Vivan Art Gallery until 4th September 2022.

Shiraz Bayjoo's new artist book, which illustrates Robert Louis Stevenson's Treasure Island, was published by Four Corners Books in May 2022.

Later this year, his work will be shown at 'Bamako Encounters, the African Biennale of Photography' in Bamako, Mali, from 20th October to 20th December 2022.