One of many things that I like about Art UK is the way that it documents the work of artists who – except, maybe, amongst other painters – have fallen out of fashion and are pretty invisible. Preserved in the storerooms of museums and private collections, these artists wait for historians to reconstruct their careers.

One of these is John Wonnacott, an artist who was well established in the 1980s and taught by Frank Auerbach and Michael Andrews at the Slade School of Art in the early 1960s.

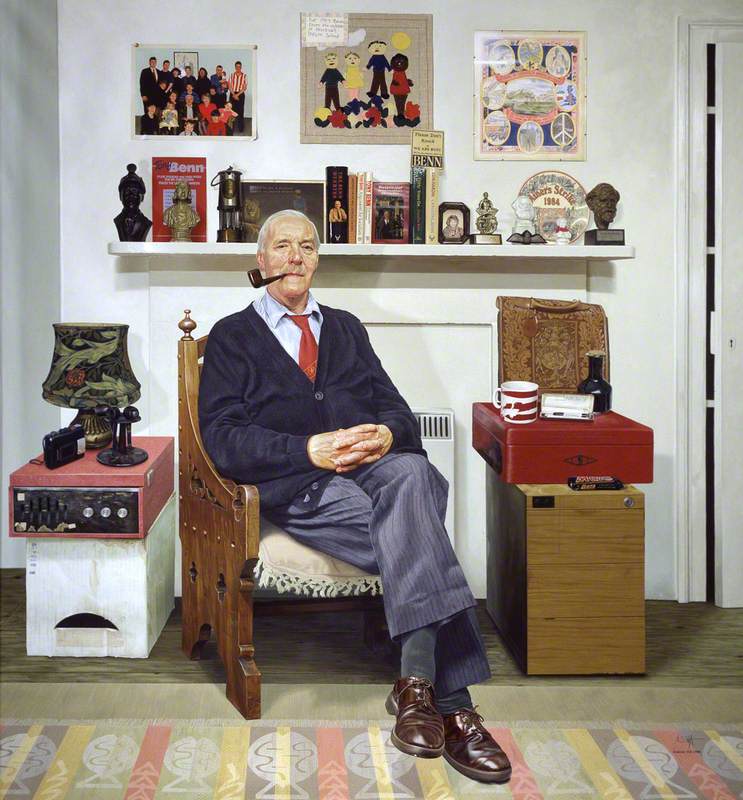

© the artist. Image credit: courtesy of the Royal Society of Portrait Painters

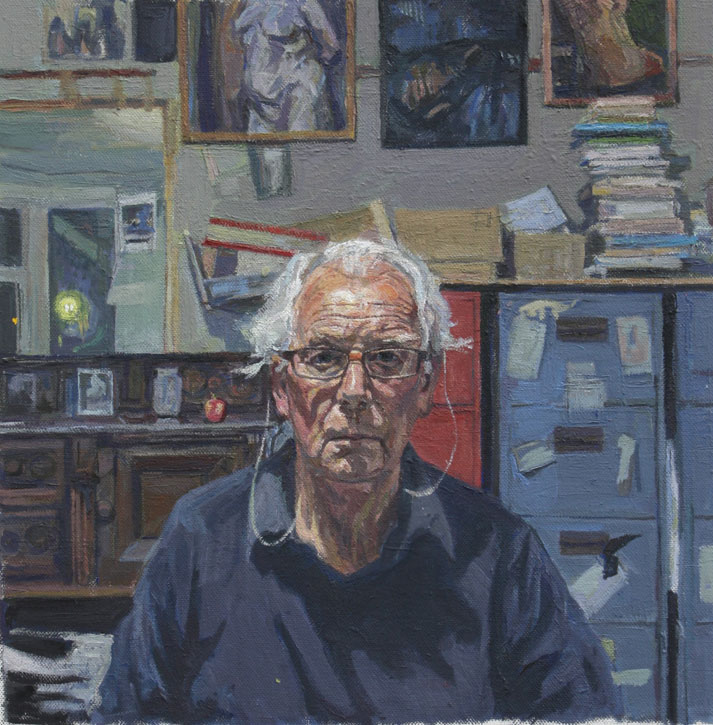

Self-portrait with apple for G

oil on canvas by John Wonnacott (b.1940)

Representative of a form of figurative painting that has largely been forgotten, his style of painting had something of a revival during the 1980s, helped by the big exhibition at the Royal Academy in 1981, 'A New Spirit in Painting', organised by Nicholas Serota, Norman Rosenthal and Christos Joachamides, and by Tate's 'The Hard-Won Image: Traditional Method and Subject in Recent British Art' in 1984.

Wonnacott was represented by Marlborough Fine Art, where he would have regular exhibitions of his work, enthusiastically reviewed in the Observer by William Feaver and in The Sunday Times by Marina Vaizey.

In 1988, he moved to Agnew's, the biggest and grandest of Old Master galleries, which was attempting to establish itself in the contemporary art market, and his work was acquired not only by the Tate, but by the Metropolitan Museum in New York, where Bill Lieberman, the chairman of the Twentieth Century Department, admired his work and acquired his Night Portrait with Blue Easel in 1993.

In the 1990s, contemporary figurative art was ultimately eclipsed by the Young British Artists (YBAs), who explored a very different set of attitudes as to what constitutes art. Figures such as Damien Hirst, Tracey Emin and Gary Hume amongst others established a different currency to art practice, which is now the established orthodoxy.

So, when during lockdown, I decided to look back at the development of Wonnacott's career in order to write a short book about his work, due to be published by Lund Humphries in early September, Art UK turned out to be an invaluable resource for documenting his work, alongside the artist's own website.

The first of Wonnacott's works to enter a public collection was the large Deposition which he himself donated to the Slade School of Art in 1963. The work reflects his intense interest in Old Master painting, as well as the influence of Auerbach, who taught a six-week course on drawing before being taken on as a tutor at the Slade in October 1963. Another early work, Elms and Trellis, Marine Parade is owned by the Government Art Collection, bought from a London Group exhibition in 1963.

After graduating from the Slade in 1963, Wonnacott devoted the next decade of his life to an intensive study of his family over time, emerging into the public eye over a decade later with a huge painting, The Family, which was shown in the Royal Academy's Summer Exhibition in 1975. Displayed on the end wall of Gallery 3, it was much admired, not least by Auerbach who brought Wonnacott to the attention of Geoffrey Parton at Marlborough Fine Art. The artist John Hoyland later included it in a survey exhibition, 'British Painting 1952–77', held at the Royal Academy in autumn 1977 to celebrate the Queen's Silver Jubilee.

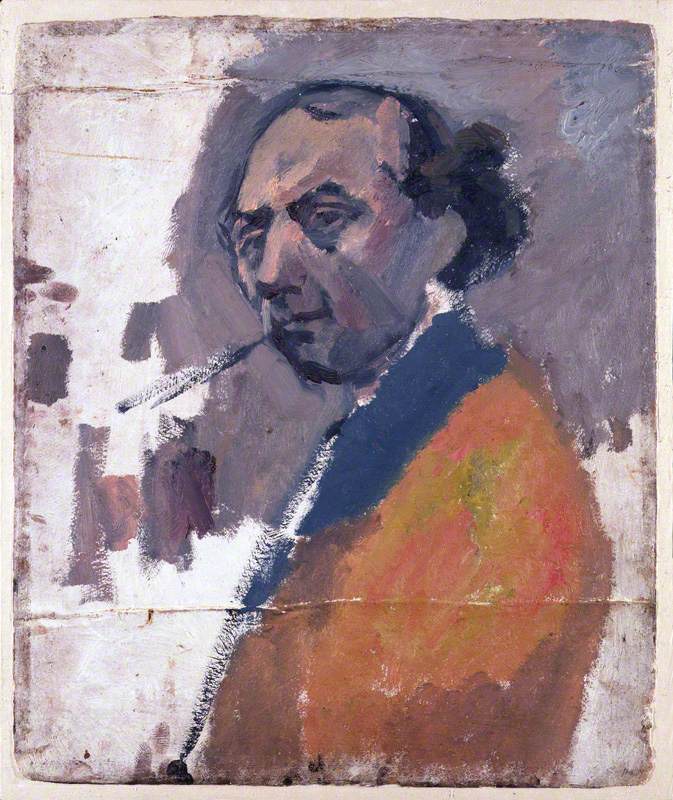

© the artist. Image credit: courtesy of the artist

The Family

1963–1974, oil on board by John Wonacott (b.1940)

This period of Wonnacott's work is documented by Crescent Road II which Rochdale Art Gallery bought in 1978 after holding and then touring an exhibition of his work. It is easy to see why this complex observational work would have made an impact in a decade devoted to minimalism.

© the artist. Image credit: Rochdale Arts & Heritage Service

Crescent Road II (The Artist and His Grandfather) 1963–1976

John Wonnacott (b.1940)

Rochdale Arts & Heritage ServiceWonnacott's work of the early 1980s is represented by two works connected to the Norwich School of Art, where he and his friend, John Lessore, taught painting from 1976 to 1986. The first is a big painting of the art school itself, Norwich School of Art which was acquired by the Tate from the Chantrey Bequest in 1984, exhibited first in the Summer Exhibition and then transferred to the Tate to be shown in the show 'The Hard-Won Image'.

It is a big, heroic piece of documentary realism, with Wonnacott himself pushing John Lessore in his wheelchair and the Victorian art school dominating the overall composition.

Norfolk Museums Service had already bought his painting The Life Room, which shows the traditional style of teaching from the life which was maintained in Norwich School of Art until both Lessore and Wonnacott were fired in 1985 for perpetuating an approach to teaching – and to painting – which was by then regarded as retrograde.

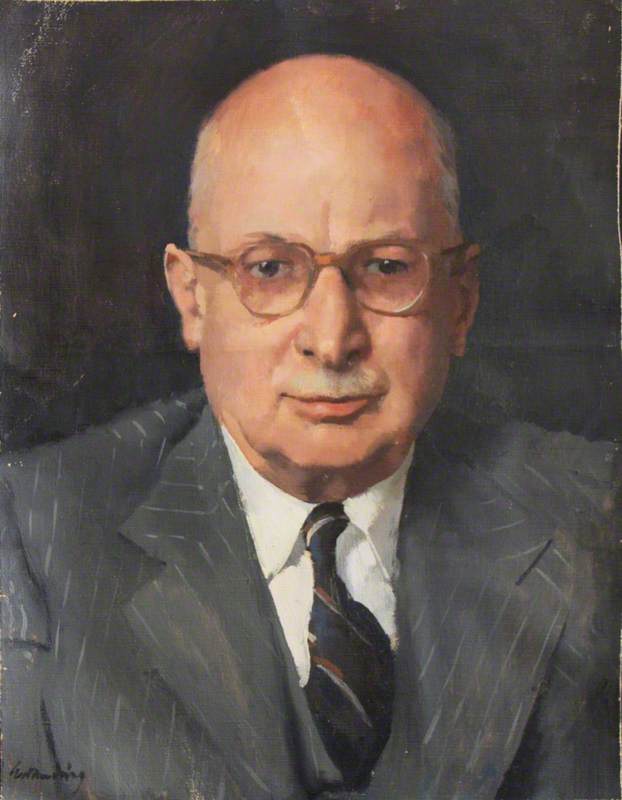

In 1986, Wonnacott was commissioned by the Scottish National Portrait Gallery to paint Sir Adam Thomson, the founder of Caledonian Airways. It is a remarkably ambitious painting, which not only shows Thomson himself leaning casually against a balustrade, but the whole interior of Hangar 3 at Gatwick Airport, where British Caledonian was based. It is strange to see a painting, which looks as if it might have been painted in the 1940s to demonstrate the anonymous heroism of industrial work.

© the artist. Image credit: National Galleries of Scotland

Sir Adam Thomson (1926–2000), Founder and Chairman of British Caledonian Airways 1986

John Wonnacott (b.1940)

National Galleries of ScotlandThere are very few other contemporary artists who could undertake, let alone succeed in constructing, a painting on this scale and of this complexity. It led to a commission from the Imperial War Museum to paint the dockyard at Devonport, Refit, Devonport, in 1989, another grand pictorial record of an industrial scene.

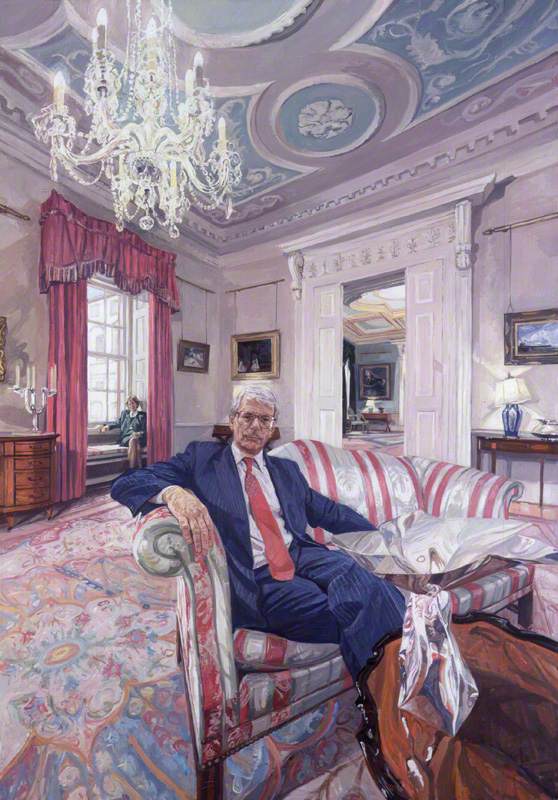

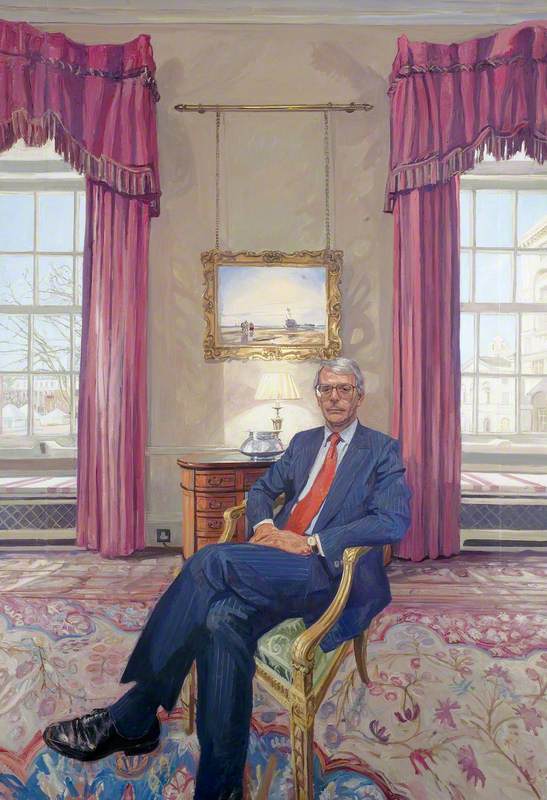

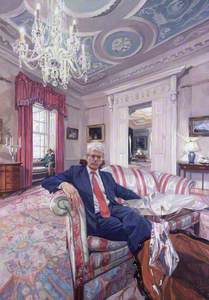

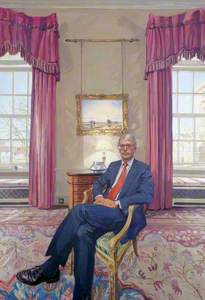

I got to know Wonnacott and his work when I was Director of the National Portrait Gallery. We needed someone to paint John Major while he was still in office and chose Wonnacott, as I remember it, because of the quality of his portrait of Sir Adam Thomson and a feeling that his style of social realism would be a good match for Major's character.

I always had the impression that they got on well together, Wonnacott spending long hours painting and drawing at 10 Downing Street, doing drawings of the White Drawing Room where Major is depicted with Norma Major on a window seat in the background. I still think that the result is a remarkably effective depiction of a politician who was perhaps uncomfortable with the appurtenances of power. Another Wonnacott portrait of Major is in the Parliamentary Art Collection.

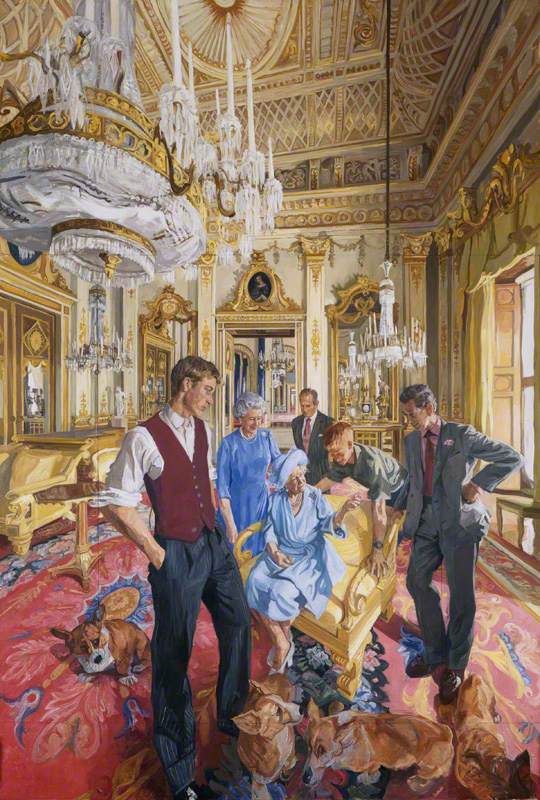

The other big commission which Wonnacott undertook while I was Director of the National Portrait Gallery was a portrait of four generations of the Royal Family to mark the Queen Mother's 100th birthday.

© the artist. Image credit: National Portrait Gallery, London

The Royal Family: A Centenary Portrait 2000

John Wonnacott (b.1940)

National Portrait Gallery, LondonThe Queen Mother dominates the composition. Prince Harry leans over her affectionately, whilst Prince William and the Prince of Wales look on. Jack Wullschlager, in a recent survey of royal portraiture, describes the painting as 'lyrical, comic, playing the ornately gilded surrounding against contemporary dress and informality'. Perhaps the corgis are comic, snapping away at the royal ankles.

Superficially, this is a highly traditional portrait, deliberately painted in such a way as to echo John Lavery's portrait of the family of George V, also held by the National Portrait Gallery.

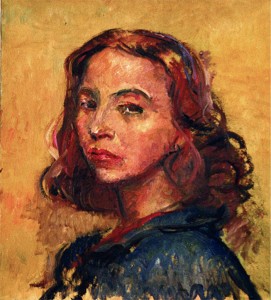

Image credit: National Portrait Gallery, London

John Lavery (1856–1941)

National Portrait Gallery, LondonSince 2000, when the National Portrait Gallery acquired the Centenary Royal Portrait, only a single work by Wonnacott has entered a public collection (a portrait of Jim Manton in Tate Britain). Agnew's moved out of their grand Bond Street premises in 2008, selling it to Etro, the Italian fashion house. Since then, large-scale figurative painting, including that of Wonnacott, has been much less visible in commercial galleries, apart from Browse and Darby in Cork Street and Piano Nobile in Holland Park, both of whom continue to show work by more traditional figurative painters.

But I can't help noticing that there is a re-evaluation going on of art between the wars, as represented by Frances Spalding's admirable book The Real and the Romantic: Art between the Two World Wars and also by Margy Kinmonth's remarkable, recent film Drawn to War, devoted to establishing the importance of the life and work of Eric Ravilious.

There is an ebb and flow to the interpretation of the art of the past and as the art of the 1980s begins to be looked at again, it is likely that a more generous attitude to the art of the period will emerge, more attuned to the breadth of art practice, and that Wonnacott will re-emerge as a figure of great interest and importance, still painting works of great skill and psychological effectiveness.

Charles Saumarez Smith, art historian, curator and author of John Wonnacott: A Biographical Study (Lund Humphries, September 2022)