Sheila Girling (1924–2015) was a British abstract artist who worked across collage, painting and clay. Her grandfather, aunt and uncle were all well-known Midlands artists and, as such, she grew up with and around art.

When still young, Girling was shown a copy of Rembrandt's somewhat macabre Anatomy Lesson in her grandfather's attic studio, which was permeated by the smell of oil paints. Despite her interest in science and medicine, it was decided from an early age that Girling would continue the artistic family line, as both an adept draftswoman and astute observer. As she noted, what was so powerful about the Rembrandt was not the corpse, but rather the way the light fell on his gently conceding figure.

© the artist's estate. Image credit: the artist's estate

Self Portrait

1948, oil on canvas by Sheila Girling (1924–2015)

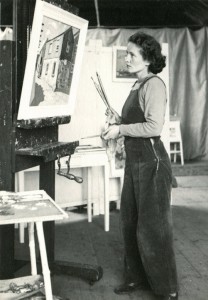

Already well versed in art history and techniques, Girling enrolled at Birmingham School of Art in 1941. As Girling remembered, unlike the generation before or after her, she went to art school at a time when women were given access to the same tools, lectures and workshops as men. It was perhaps one of the only benefits of studying during the Second World War, and reflective of her own family's unconventional support of her artistic career.

Then, in 1947, she was awarded a scholarship to the Royal Academy Schools in London. This scholarship afforded her financial freedom from her parents, as well as access to exhibitions of cutting-edge works by figures such as Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso and Prunella Clough. Girling's ambitious graduate work, Return of Ulysses, is a prime example of these artists' impact on her work, especially Clough.

© the artist's estate. Image credit: the artist's estate

Return of Ulysses

1949–1950, oil on canvas by Sheila Girling (1924–2015)

After graduating, Girling moved into a studio in artist and architect Mario Manenti's 'Italian Village' on the Fulham Road, with her new husband, the British sculptor Anthony Caro (1924–2013). This was a joyful and productive period during which Girling and Caro produced artworks side by side; as columnist Pamela Black noted in the Evening Standard in 1950, 'Sheila paints in the gallery while downstairs Anthony is working on a model of a life-size nude'.

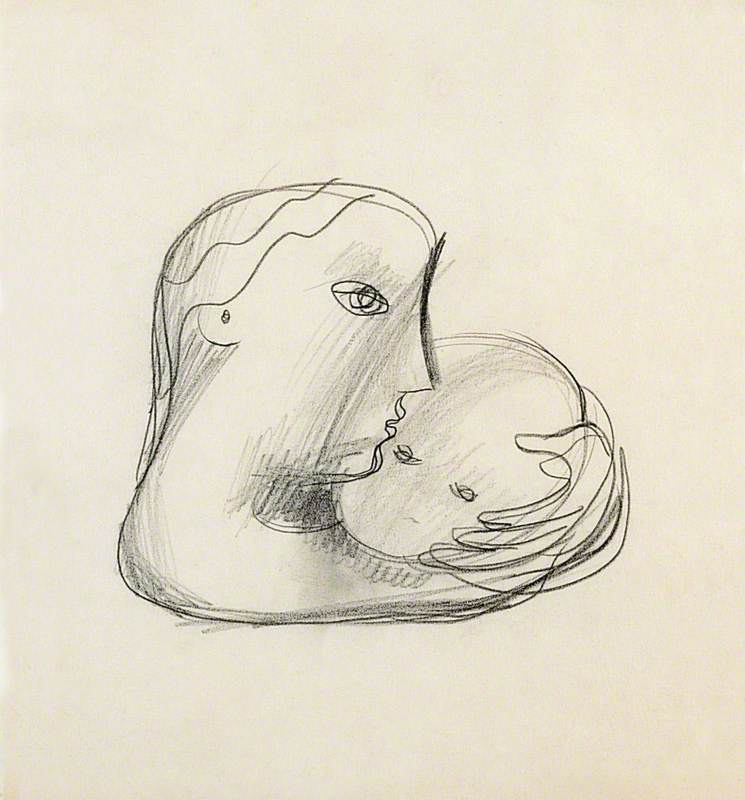

Then, in 1951, Girling gave birth to her first son, Tim, at which point she decided to commit her time to his upbringing and the support of Caro's practice. Famously, Girling worked closely with Caro to select the colours of his sculptures, choosing and applying the paint to Early One Morning (1962) and Month of May (1963), then much later selecting the blue of the Perspex disc in Blue Moon (2013), amongst many others. This was an especially difficult period of her life as a young mother, marked by periods of depression as well as long stretches of time alone whilst Caro was at work in the USA.

However, over this period (1953–1973) Girling remained deeply enmeshed in the most challenging and exciting conversations about abstract art in the UK and the USA, not only with Caro but with art critics such as Clement Greenberg (1909–1994) as well as artists including Kenneth Noland (1924–2010), Helen Frankenthaler (1928–2011) and Jules Olitski (1922–2007). Girling's relationships with Noland and Frankenthaler were especially profound, developed in the 1960s whilst Girling and Caro briefly lived together in Vermont. As such, when her children Tim and Paul had grown up, she returned to painting with a radical new approach and an immense energy to create.

© the artist's estate. Image credit: the artist's estate

Second

1973, acrylic on canvas by Sheila Girling (1924–2015)

This is exemplified in Second (1973), one of the first large-scale acrylic paintings that Girling made upon her return to the medium, which stretches over three metres high and overflows with a certain affirmation of life. Throughout the 1970s, Girling produced a vast body of large-scale canvases that are vibrant, bursting and full of movement, calling upon the unique qualities of acrylic paint and informed by her time living and working alongside the Colour Field painters in Bennington, Vermont. In contrast to the traditional education in drawing and painting that Girling received in post-war Britain, her abstract canvases were made by pouring, mopping and layering acrylic paints onto expansive horizontal plains. These paintings are hopeful and joyous in their expression of colour, vitality and movement.

In 1978, Girling took part in an intensive clay course with ceramicist Margie Hughto (b.1944) in Syracuse, New York. Here she made a series of over 100 tactile and elegant pressed slabs – made by putting pigment in rather than on the clay. Later that year Girling's first major solo show 'Watercolour Landscapes' opened at Edmonton Gallery in Alberta, USA, touring to Calgary Art Gallery and Everson Museum of Art. For Girling, the possibilities of painting were radically expanded when she began using acrylic, a water-based medium that could be manipulated like watercolour to stain and pigment canvases.

Then, in 1980, she had her first of a series of solo shows at Acquavella Contemporary Art in New York. Acquavella was becoming known for exhibiting and dealing in 'the masters of post-war American painting and sculpture'. For Girling, the importance of Acquavella's support cannot be understated; it represented not only a recognition of her significant contribution, but also the success of her career, distinct from that of Caro, within the history of art. As this new stage of her career developed, Girling began to build relationships with further galleries, including Francis Graham Dixon, Flowers Gallery and later Annely Juda Fine Art in London, who would go on to represent her work in the UK.

In 1982, Girling established Triangle Artist Workshop with Caro, curator Terry Fenton and philanthropist Robert Loder, with the aim of connecting abstract sculptors and painters first across the USA, Canada and the UK, then across the world. The workshop still runs today and supports some of the most innovative and experimental practices in contemporary art.

From this point onwards, the majority of Girling's abstract canvases stretch beyond the scale of the human body, either on a vertical or horizontal plane, oftentimes both. This scale enabled her to paint experientially, from within the canvas. As British art historian Hannah Westley writes, this 'cannot be underestimated when considering how a viewer apprehends the work...the scale is experienced more directly and more consciously felt'.

Mediated by a shared sense of space and scale, Girling's later architectural and figurative canvases often dwell in the relationship between the internal and external worlds of the painting and its subjects, exemplified in works including Tête à Tête (1992) and Way Through (1995). Speaking about this sense of bodily and psychological immersion, Girling reflected: 'I paint on the floor to be able to enter into a painting; I want to live in the space I am making'.

© the artist's estate. Image credit: the artist's estate

Way Through

1995, acrylic & collage on canvas by Sheila Girling (1924–2015)

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, she began making smaller, cut pieces out of handmade, coloured paper and off-cuts of painted canvas. Some of these works are raw and immediate, like Stanza (2013), which flutters in frenetic bursts across flecked paper, whilst others have a balanced set of contemplated internal relations, such as the works that make up the 'Cathedral Series' (2008). For Girling, the immediacy of collage enabled her to think in space with colour, texture and shape, whilst its fragmentary nature allowed her to create images that sat between figuration and abstraction. Like her paintings, Girling's collages are marked by their intensity and energy for life.

Despite her extraordinary career and oeuvre, Girling's works have received very little recognition in galleries and museums in the UK. This is not wholly surprising given what Consuelo Ciscar Casabán calls the 'almost insurmountable obstacles' faced by women artists of her generation, not to mention the success of her husband, which at points drew time and focus away from her own artistic career. However, in 2006, IVAM, Spain staged the first retrospective of Girling's work and in 2019 a group of works, including the painting Light Lunch (2006), was collected by the Yale Center for British Art.

© the artist's estate. Image credit: Yale Center for British Art

Light Lunch

2006, acrylic & collage on canvas by Sheila Girling (1924–2015)

This summer, a major UK retrospective of Girling's life and career opens at Space to Breathe, Bowhouse, in Fife to mark the centenary of her birth. As Ciscar Casabán wrote in the catalogue for Girling's retrospective at IVAM, these art historical revisionings are of incredible consequence, because 'a newly discovered woman becomes more and more the protagonist of this century, so that her rise personifies life itself and the development of many spheres of life depends on her'.

Kathryn Cutler-MacKenzie, Project Assistant, Sheila Girling Studio

'The Life and Career of Sheila Girling' at Space to Breathe opens on 20th July and runs until 1st September 2024