In honour of Shakespeare's anniversary on 23rd April, the Royal Shakespeare Company actor and two-time Laurence Olivier Award winner Sir Antony Sher examines three depictions of Macbeth on Art UK.

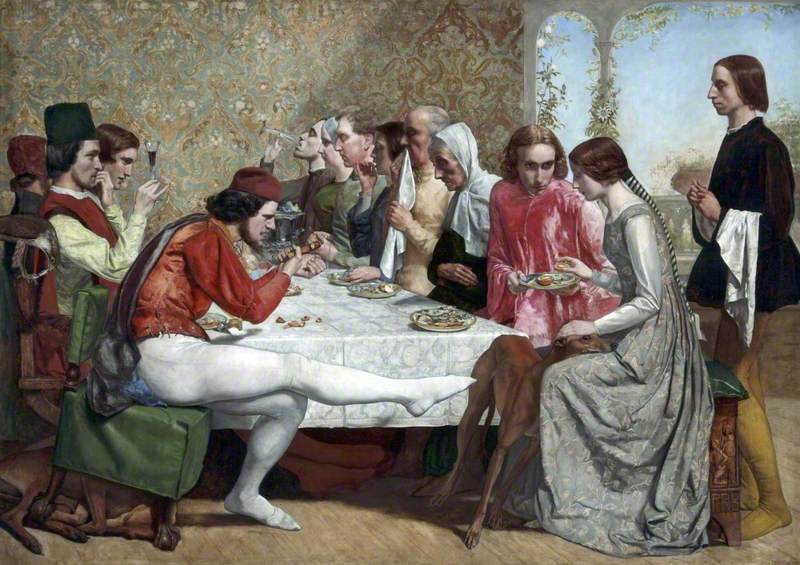

I'm looking at three artworks which are depictions of Shakespeare's great play, Macbeth. Two are by world-famous painters, and one is, rather presumptuously, by me.

Firstly, a painting of the three Witches by Henry Fuseli.

Image credit: Royal Shakespeare Company Collection

'Macbeth', Act I, Scene 3, the Weird Sisters c.1783

Henry Fuseli (1741–1825)

Royal Shakespeare Company CollectionHe was a renowned painter of Shakespearean subjects (his Midsummer Night's Dream pictures are particularly fine, teeming with bizarre miniature fairies), and in 1783 he sought to portray the Witches in Macbeth.

He returned to the subject several times, but my personal favourite is the one in the Royal Shakespeare Theatre collection. It is a long, horizontal oil painting, showing profiles of a trio of old-ish female figures, wearing hooded cloaks, and all pointing to the left with their left hands while their right hands are held to their jaws. The first impression is that their tongues are hanging out, but, on closer inspection, these fleshy, vaguely obscene protuberances are in fact their forefingers. Fuseli is illustrating Banquo's line in Act 1 Scene 3, when he and Macbeth first encounter the Weird Sisters:

'Each at once her choppy finger laying upon her skinny lips.' (Choppy means chapped.)

What strikes me is how Fuseli's composition captures the essence of the witches' dreadful prophecies. The sloping hoods along the upper half of the image, the outstretched arms along the lower – these both leading to a tapering perspective of aimed fingers, the front witch's digit providing the sharp tip, and creating a kind of arrow. An arrow of evil, as I see it. This is the only direction Macbeth can take, and it will lead to terrible violence and destruction, his own included.

Image credit: Wellcome Collection

Macbeth and Banquo Meet the Three Witches on a Heath; Scene from Shakespeare's 'Macbeth'

Henry Fuseli (1741–1825) (after)

Wellcome CollectionIn any contemporary production of Macbeth, the Witches' scenes are immensely challenging to stage, and the roles difficult for actresses to interpret. In Shakespeare's day, witchcraft was a recognisable part of society, a feared subculture. But in our times – or in the West, certainly – it is dismissed and satirised.

When witches appear in popular films or drama, they tend to be Disneyesque caricatures: hunched crones with hooked noses, warts, and riding on broomsticks. Not best equipped to drive the dangerous engine of Shakespeare's story. It takes considerable imagination to conjure up an impression of witches which still send chills up your spine. Yet that's exactly what Fuseli's painting does.

My next choice is John Singer Sargent's 1889 oil painting, Ellen Terry as Lady Macbeth.

A tall, imposing, full-length portrait, it depicts the famous actress in Sir Henry Irving's 1888 production at the Lyceum Theatre, London, in which he also played the eponymous lead.

Terry stands upright, lifting the crown above her head – her thick red hair hanging in long heavy plaits, her blue eyes luminous with ambition. This actual moment – Lady Macbeth about to crown herself – never actually featured in Irving's production, so one can only presume that Sargent is visualising a fantasy from her subconscious: her own craving for ultimate power, lying behind her assurance to Macbeth in Act 1 Scene 5 that she will drive away...

'All that impedes thee from the golden round,

Which fate and metaphysical aid doth seem

To have thee crowned withal.'

As with the Witches, the role of Lady Macbeth carries an inbuilt risk for any actress playing her: the temptation to indulge in 'Wicked Acting'. But Terry seems to have sidestepped the trap (if Sargent's portrait is an accurate reflection). Here is not a fiendish, scheming villain, but a proud, strong woman with her own private agenda. Her character is not clichéd, it's complicated.

A spectacular aspect of Terry's performance was her costume. A close-fitting turquoise dress, it was decorated with 1,000 wing cases from the green jewel beetle, which gave the impression both of soft chain mail and the scales of a serpent.

Sargent insisted that she wear it for the portrait sittings in his Tite Street studio. One of his neighbours was Oscar Wilde, who was fascinated by how her arrivals by carriage, in full regalia, transformed their ordinary surroundings. Of her fabulous dress he observed, 'Judging from the banquet, Lady Macbeth seems an economical housekeeper, and evidently patronises local industries for her husband's clothes and the servants' liveries; but she takes care to do all her own shopping in Byzantium.'

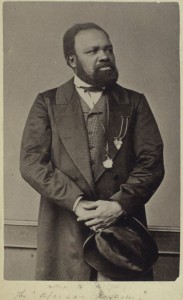

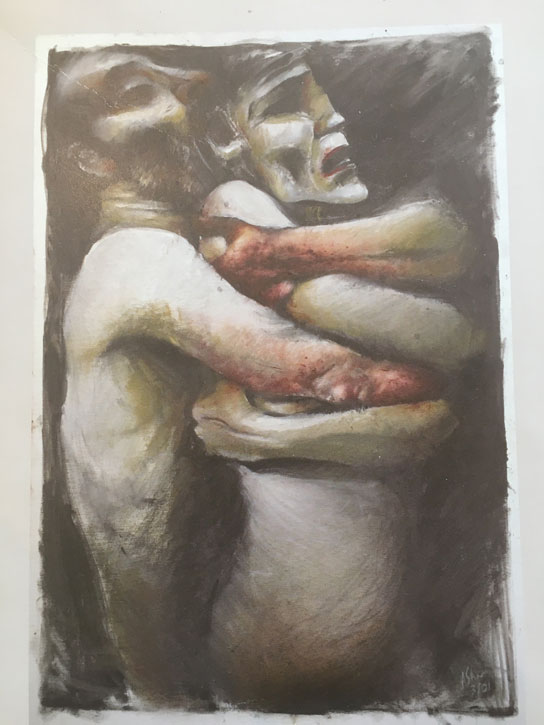

Driven by hubris, my third choice is one of my own works: an oil painting I did in 2001, called The Macbeths, and based on the RSC's 1999 production, directed by Greg Doran, who is now Artistic Director of the company. (He is also my husband.) It co-starred Dame Harriet Walter and myself, and we are portrayed here.

© the artist. Image credit: the artist

The Macbeths

2001, oil on canvas by Antony Sher (b.1949)

As I've mentioned, the play's themes of witchcraft and murder can lead to some Grand Guignol excesses, and many productions have floundered on this charge – so many that the piece has developed an unlucky or sinister reputation, and the majority of theatre people won't say its name, preferring to call it 'The Scottish Play'.

On the first day of our rehearsals, Greg announced to the company, 'There is no supernatural curse on Macbeth – the only curse is that it's very hard to get it right.'

His solution was to go for a stark and brutal simplicity: virtually no set, just the bare Swan Theatre stage, and no music except percussion. The rest was done with lighting and acting: fast, urgent, intimate acting.

My picture was done in the same spirit, and is an attempt to show not an actual moment from the production, since none such existed (as with Ellen Terry crowning herself), but rather what the experience felt like: a husband and wife entwined in a tight, deadly embrace, caught up in a chaos of their own making. I remember being inspired by Macbeth's lines in Act 1 Scene 7:

'And pity, like a naked new-born babe

Striding the blast, or heaven's cherubin, horsed

Upon the sightless couriers of the air,

Shall blow the horrid deed in every eye,

That tears shall drown the wind.'

I'm very proud of having been in the production – which played in Stratford, London, Tokyo, New Haven, and was filmed by Channel 4 – and I like to think that the painting catches something of what we were striving to do: touch the dark heart of that remarkable play.

Sir Antony Sher, Royal Shakespeare Company actor and artist