Scottish conceptual artist Scott Myles is interested in social structures of exchange, creating artistic interventions that subtly subvert the transactional logic of capitalist commerce.

Working in a wide range of media including painting, screenprinting, video, sculpture and sound, his latest exhibition at Glasgow's Gallery of Modern Art (GoMA), 'Head in a Bell', takes its title from a 1962 photograph of the composer John Cage, in which he is pictured with his head inside the bell of a Japanese Zen temple.

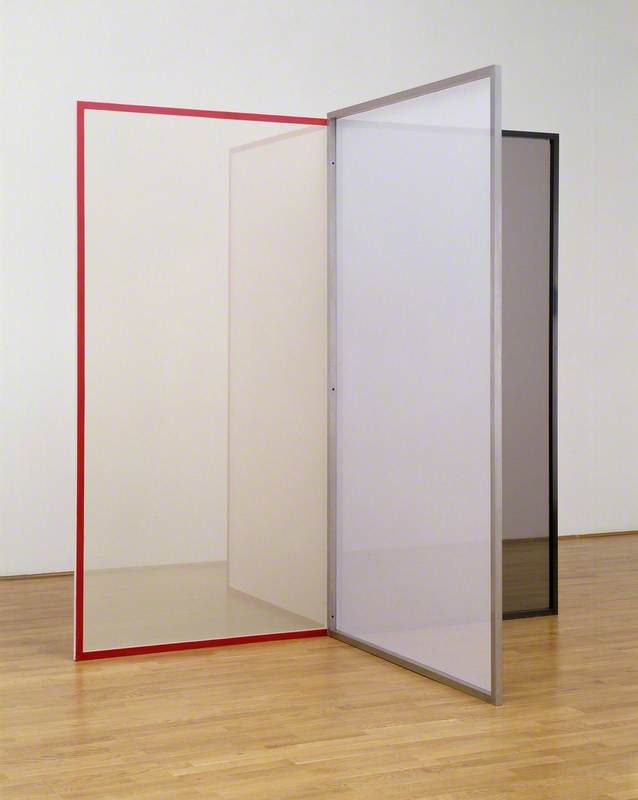

Installation view, 'Scott Myles – Head in a Bell', Gallery of Modern Art, Glasgow, 2024

The exhibition centres around a sound sculpture consisting of modular synthesisers donated to the artist by companies from around the world, which is linked to a live sound feed of the gallery's air circulation system. Also featured are altered found objects, paintings, screenprinting and a stack of free posters for visitors to take away.

Born in Dundee and based in Glasgow, Myles graduated from Dundee's Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art in 1997 having studied drawing and painting. Eschewing a consistent visual style, his ideas-driven practice often involves everyday objects and actions. His 2002 sculptural work Ice Cream Paperweights (Brown, Pink, White, Taupe, Green), for example, saw him bronze-casting scoops of ice cream, while his 2012 piece, Analysis (Mirror) consists of bus shelters upturned one on top of the other and painted with the precious metal silver.

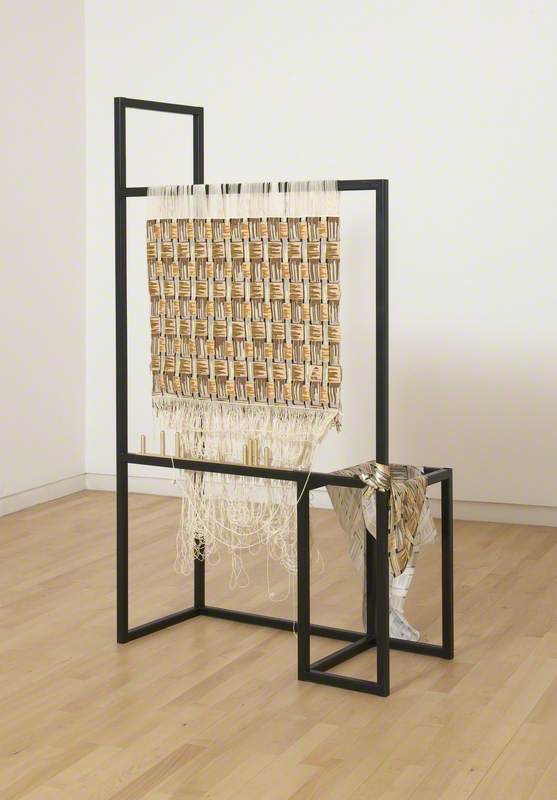

Analysis (Mirror)

2012, found object, silver & UV lacquer by Scott Myles (b.1975)

Explaining his difficult-to-pin-down practice, Myles says: 'As an artist, I'm looking for the spaces in between, things that, for me, might be situations that I can work with.'

Installation view, 'Scott Myles – Head in a Bell', Gallery of Modern Art, Glasgow, 2024

Chris Sharratt: Your current exhibition at GoMA, 'Head in a Bell', has at its heart the work Instrument for the People of Glasgow, comprised of donations from Eurorack synthesiser manufacturers. You describe it as a 'social sculpture' – can you explain how it came about?

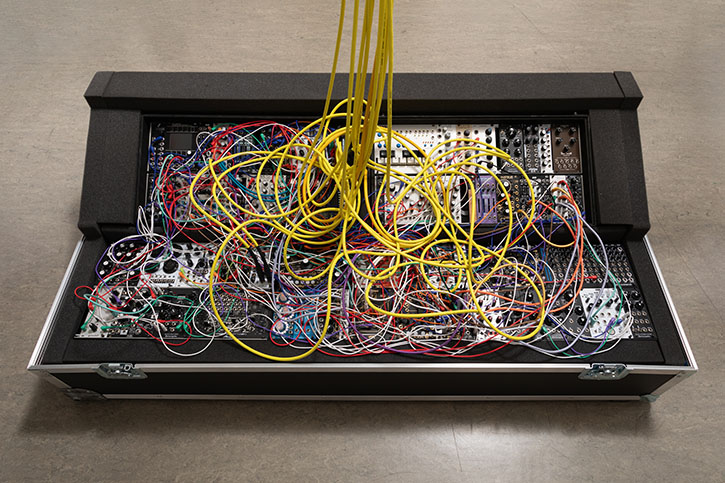

Instrument for the People of Glasgow

2023-2024, donated Eurorack synthesiser modules, two ADAM Audio speakers, flight case, silkscreen, cables & Perspex by Scott Myles (b.1975)

Scott Myles: It's an artwork that's arisen following six years of exploring sound as a material, and lately sound synthesis specifically. The work consists of separate Eurorack modules from companies I approached in Berlin while visiting Superbooth, a trade fair and festival for electronic musical instruments. I gave them all a letter outlining the project, and over the past year boxes arrived at my studio containing small and beautiful electronic modules from many countries across the globe. To date, over 70 Eurorack modules have been donated.

The modules are coming out of a kind of bespoke cottage industry, but when plugged together into a patch, they generate something quite powerful, and infinite. There's a live-ness to modular synths, a kind of understanding that things will rarely sound the same, or repeat. This fascinates me as a symbol of potentiality. I'm also interested in the performative aspect, which is apparent in other artworks and projects I've made.

Installation view, 'Scott Myles – Head in a Bell', Gallery of Modern Art, Glasgow, 2024

Chris: When the exhibition finishes in February 2025, you will donate the work to Glasgow Library of Synthesized Sound (GLOSS). Why is it important to do that?

Scott: My original idea back in early 2023 was for the sculpture to be donated to Glasgow's Mitchell Reference Library, where there are carrels – small rooms people can rent to practice playing an instrument. The idea was that anyone interested in playing and experimenting with it could access the work free of charge: I have a son who's 14, and I like the idea of a boy or a girl or anyone going up to the desk saying, 'Can I borrow the synthesiser?'

Installation view, 'Scott Myles – Head in a Bell', Gallery of Modern Art, Glasgow, 2024

Last year, as I spoke to people about what I hoped to do, I learned about GLOSS, a project by musicians Lewis and Suzi Cook from the band Free Love. I met with Lewis and decided that GLOSS – which is a community interest company and the first electronic music instrument library in the UK – should be the destination for the sculpture. They'll provide access to this modular instrument as part of their activities: education, workshops, performances, etc. It's really important to me that it's used in a real-life context.

Chris: You've also collaborated with the artist Oscar Prentice-Middleton to create the piece Air is Moving, a live sound feed of GoMA's air circulation system. What's the thinking behind this?

Air is Moving (detail)

2024–2025, live sound feed from gallery plant room, four omnidirectional seismic measurement microphones adjusted for field recording, two basic Ucho microphones, cables & Eurorack modules ('Instrument for the People of Glasgow') by Scott Myles (b.1975) & Oscar Prentice-Middleton

Scott: As the idea of presenting the Eurorack module sculpture grew, I became aware of a sound already present in the gallery which emanates from an air exchange handling system in GoMA's plant room. I began thinking about how this represents the infrastructure of the institution – the container that presents the art – and whether we could somehow put this sound through the synthesiser. And so working with Oscar, that's what we've done, miking up the air handling system for the gallery using geophone field-recording microphones placed in the plant room and the four air vents in the gallery itself.

Installation View of Homebase Kitchen Department (June 13–June 21 1997)

1997

Scott Myles (b.1975)

Chris: Working with something as functional as an air circulation system chimes with previous works you've made that reference the objects and structures that form part of our everyday environment – window frames, bus shelters, furniture, shelves, locks. How do these choices relate to the themes of your work?

Scott: Whether it's the brick walls that were built in Dundee Contemporary Arts [Displaced Façade (for DCA), 2012], which were a reference to an architectural practice site, or employing someone to conduct a cigarette break [Untitled (Smoking), 2001], as an artist I'm interested in context, and in situations where art can arise. In this instance, it was about following the source – like, where's that sound coming from?

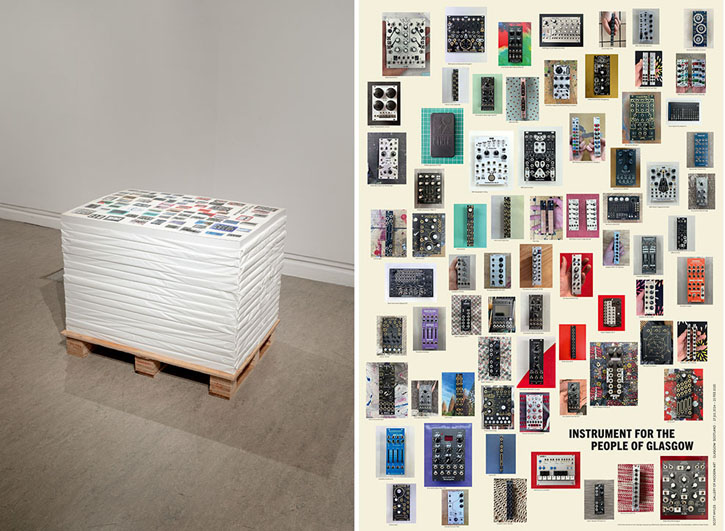

Instrument for the People of Glasgow (poster)

2024, four-colour offset print on paper by Scott Myles (b.1975). Installation view, 'Scott Myles – Head in a Bell', Gallery of Modern Art, Glasgow

Chris: The GoMA exhibition includes a free poster for visitors to take away. You've worked with the poster format previously – can you explain its role in your practice?

Scott: The first works I produced with posters occurred over 20 years ago when I used the reverse blank sides of Félix González-Torres posters. González-Torres' themes were transience and dissolution of his own work, but also tied to generosity and gift exchange. My artworks took up González-Torres' themes as I complicated the gesture, painting sentences onto the posters such as Inside Sailing (2002), Learn the Language (2003) or Performance Now (2004).

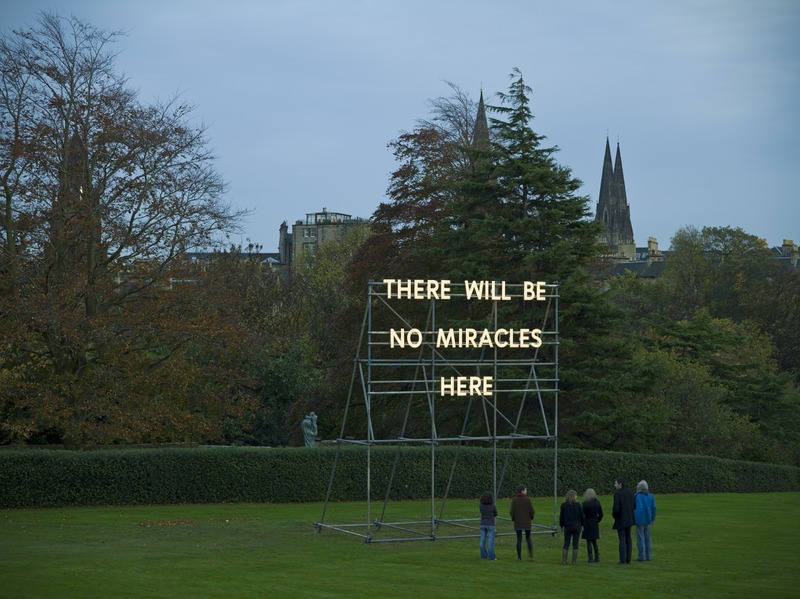

Potlatch

2014, documentation of a project for Lafayette Maison, Paris (in collaboration with Fondation Lafayette) by Scott Myles (b.1975)

Ten years ago, I explored the idea of an artwork that would be given away to the public in Lafayette Maison department store in Paris. With Potlatch (2014), I initiated a subtle intervention that involved gifting an artwork within a situation of commerce. The white tissue paper used to wrap purchased goods was temporarily replaced with paper prints of twelve colour photographs of Guy Debord's home in France. Like with my new artwork, Instrument for the People of Glasgow (poster), I'm curious to see the posters going out into the world, reaching an audience my larger-scale works can't.

Chris: You've always worked in a lot of different mediums: sculpture, painting, screenprinting, video, found objects. Can you talk about how you navigate these different approaches?

Scott: An easy answer would be to say that my medium is ideas – my approach to art is conceptual. But I have a wide interest in different creative forms and formats. For me, there's always an element of reality occurring – what resources are available to me for the making of a particular art piece? My studio right now in Glasgow, for example, is set up as a print studio, because I wanted to have a situation where I could have more freedom to experiment with print. But that's also coincided with austerity, the pandemic and economic reality.

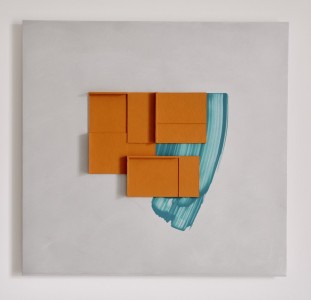

Keys (IV)

2024, oil & silkscreen on canvas by Scott Myles (b.1975)

I guess the artists that I like are often ones that don't have an immediately recognisable style or form. The accusation, 'Scott Myles, your work looks like a group show', is painful to hear, but maybe I also carry it as a badge of honour, in a way. I think I work that way because I want to keep it interesting for me.

Able Inhaled

2024, acrylic on canvas by Scott Myles (b.1975)

Chris: So, with that eclectic approach in mind, what's next?

Scott: I feel like the next show might do something different again. I studied drawing and painting at Dundee, and I think increasingly that paint, and the freedom of painting, is of interest to me. The Able Inhaled (2024) painting in the GoMA show, and before that 2022's Big Car painting [of an American 'muscle car'] have been somewhat large-scale experiments in how I might use paint. That feels like something that, yeah, I could spend the rest of my life trying to do.

Chris Sharratt, freelance writer

The exhibition 'Scott Myles - Head in a Bell' is showing at Glasgow Life's Gallery of Modern Art until 23rd February 2025

This content was funded by the PF Charitable Trust