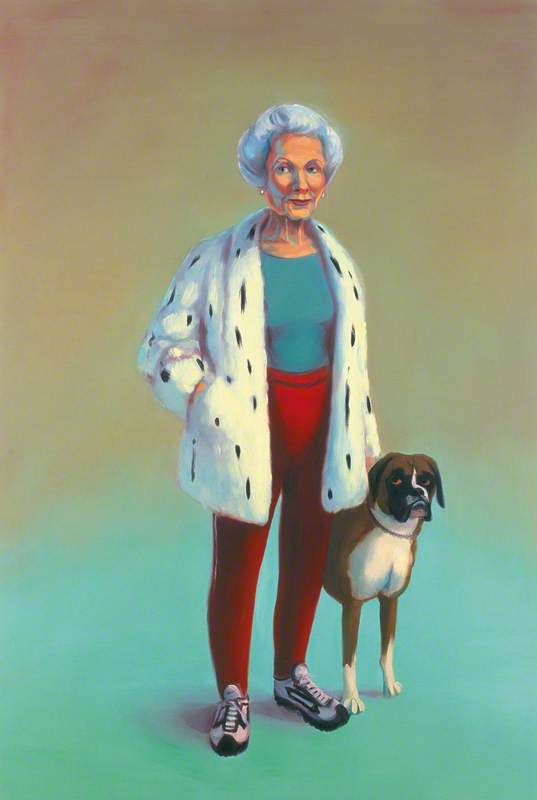

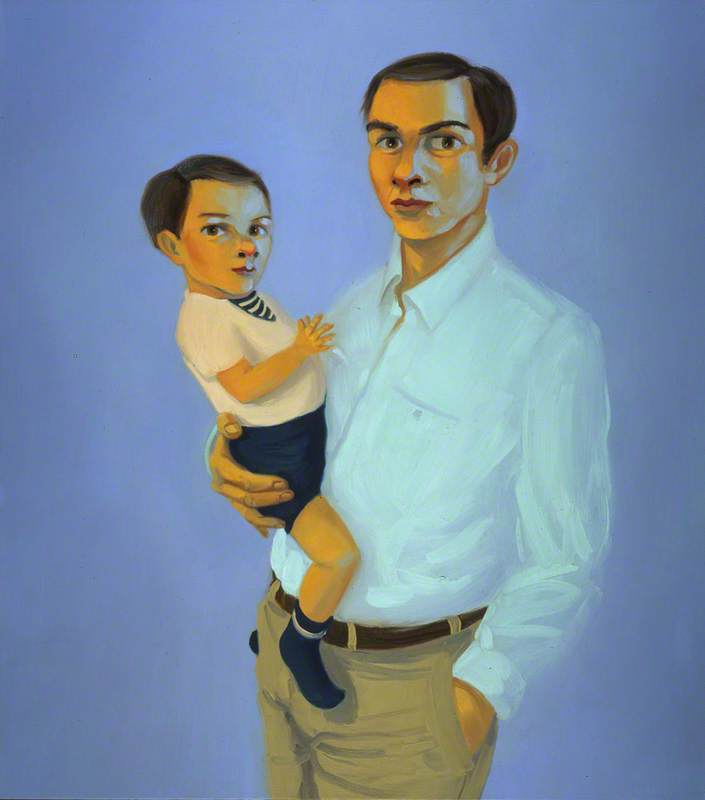

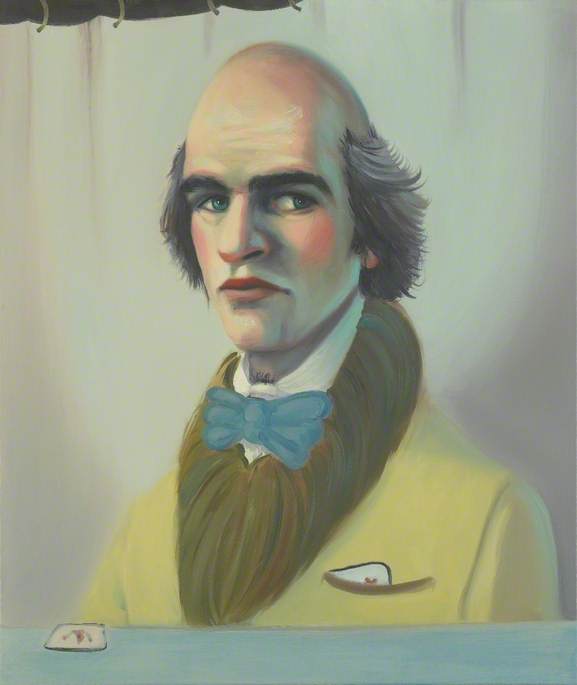

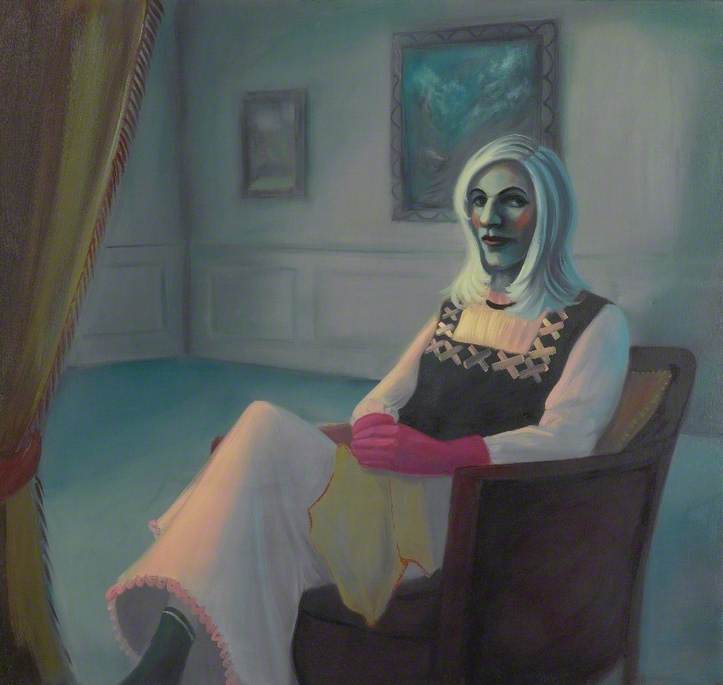

Moyna Flannigan (b.1963) is a Scottish artist based in Edinburgh. Known for her paintings that focus on women, her inspiration is drawn from myth, art history and pop culture, creating works that interweave visual memories and experiences.

Flannigan studied at Edinburgh College of Art and is now a lecturer there. She also received her Masters at Yale University School of Art. She recently presented a new body of work at Collective in Edinburgh as part of its 40th anniversary. 'Space Shuffle' was created in response to Collective's City Dome Gallery, and featured collages alongside a constellation of paper sculptures which extended the principles of collage into three-dimensional form and space.

Jennifer McLaren: Can you tell me about the significance of the figure in your work?

Moyna Flannigan: It's through a fascination with looking. I have a very natural, strong internal visual language and a visual memory and I'm interested in how things exist in the world. How I make sense of the world is through looking and inevitably that becomes a kind of mirror to the self: how do you represent, not necessarily myself, but ourselves?

There's a line in Robert Burns's poem, 'To a Louse': 'To see oursels as others see us'. In it, there's a woman sitting in church and a louse is crawling about the back of her hair that she doesn't see – but it's impossible to see her without seeing the louse, so I think that's quite interesting. Also at the beginning of Camera Lucida by Roland Barthes, he says how he came across a photograph of Napoleon's brother and realised that he was looking into the eyes that had looked at the emperor. So there's this idea of: what is it we're seeing? And I think, in a painting, it's fiction – because the language is not the same as reality.

I also think the greatest paintings in the history of art (besides a few by Kazimir Malevich, Ad Reinhardt and Frank Stella) are figurative paintings. The first time I went to The Prado and saw Velázquez's Las Meninas, I'd seen it in books hundreds of times but it's absolutely vast and so compelling visually it makes you gasp. Although it's from several hundred years ago, it feels very potent and resonant now. How you represent the people of your time – that's the most interesting thing to me.

Jennifer: How has your practice and style developed over your career?

Moyna: I'm a great magpie. An aspect of my work that was considered quite innovative and original was the sheer range of references that went into the work – from the very deep past to fashion and literature and so on. The idea of building up this vast mental library of images and ideas to draw on has propelled my career.

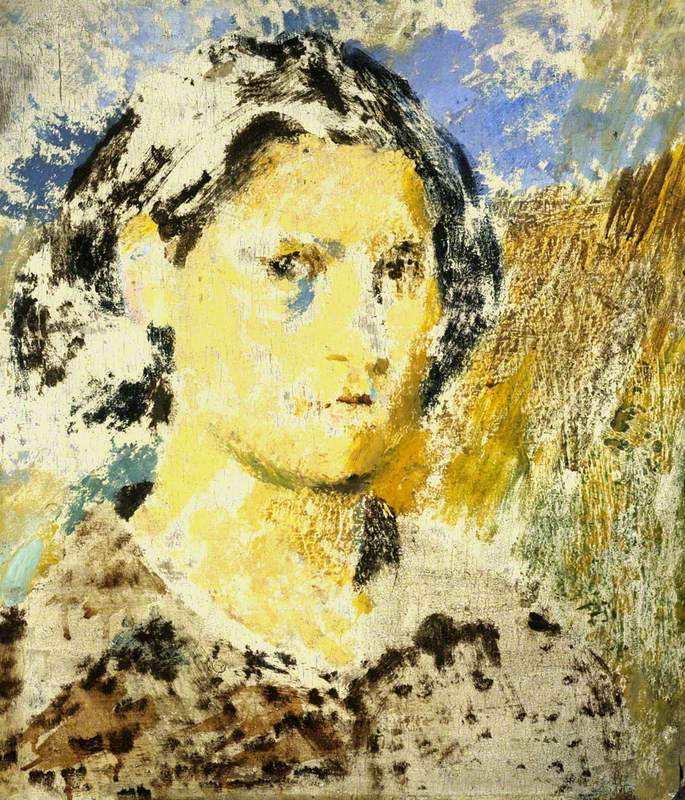

At art school, you're just taking everything in, but you don't know that much. I feel like I know an enormous amount now. And I feel, in some ways, that the subject was there right at the beginning. Some of the themes I work on have been current throughout my career, but the way I've tried to represent them has changed.

I think you have to work through different ways of painting – different ways of art-making – to find what it is that's the most powerful language for you. I've never been very interested in a signature style. I'm not that sort of artist; I'm always looking for a new way of seeing.

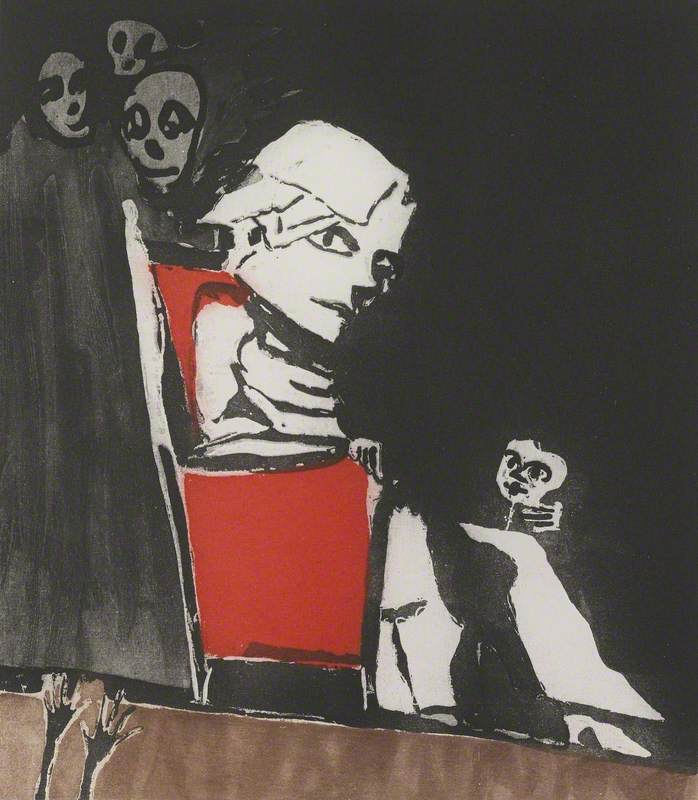

There was a dramatic change in my work in 2016, where I had been painting in oil for a long time up to that point, and then I just stopped. All artists develop habits – certain ways of making work – and I was frustrated with those habits. And so, after a three-month period of drawing, where I produced a lot of drawings that didn't do what I wanted them to do, I started ripping them up out of frustration. They became the basis for the first collages.

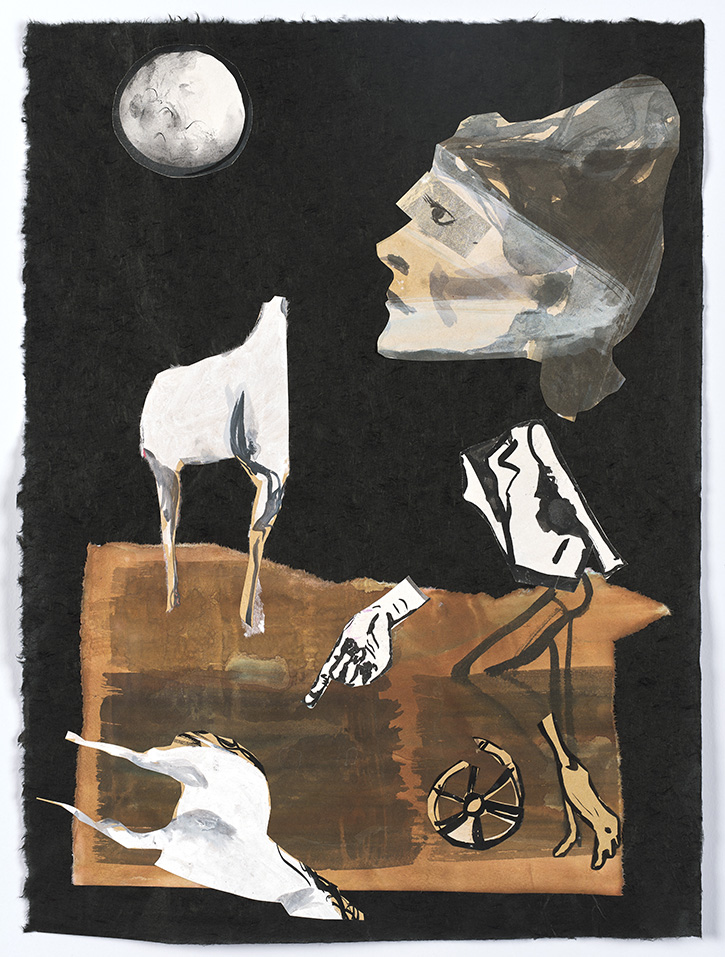

Cosmic Traces 1

2023, ink & gouache on Japanese paper by Moyna Flannigan (b.1963)

It was incredibly exciting and opened up a whole new way of working and the idea of chance. You could move things around all the time and completely change what they were.

I saw a show of Hannah Höch at the Whitechapel Gallery, which influenced me, and I also saw a show of Matisse's cutouts, which I had never liked in reproduction. Then I actually saw the show and the cutouts are much more tactile than you think. He would pin lots of pieces together onto a board: something you saw as a big white shape in a reproduction was actually made out of lots of different pieces.

All these things became the springboard for developing new work.

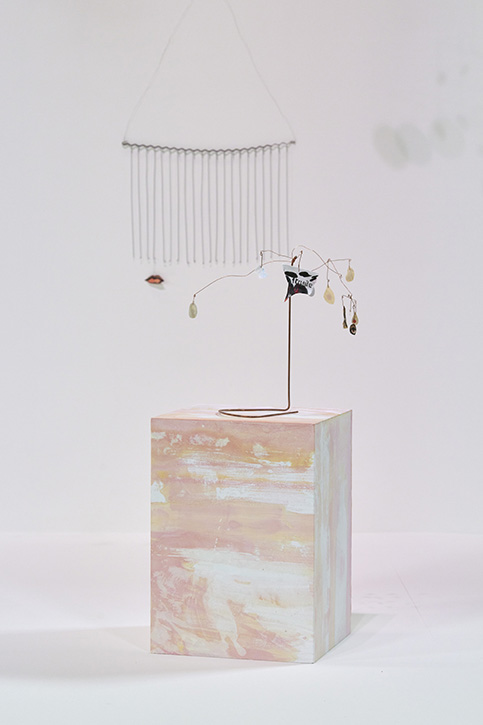

'Space Shuffle', Collective, 2024

Moyna Flannigan (b.1963)

Jennifer: How does the use of three-dimensional form impact your work?

Moyna: If you are making paintings within a rectangle, there's a certain frustration around that limitation. And so, over the past 10 years, I've made sculptures in different sorts of ways, almost as a corrective: what happens if you make a thing that exists in the world? Because a painting will just sit there and do nothing. I think the idea of these paper sculptures on wire armatures was that they would move, and that's a thing that a painting can't do.

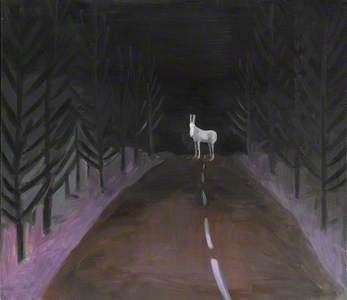

I've always been interested in film, particularly the films of Andrei Tarkovsky, because he makes films like a painter and slows down time.

The idea of creating movement is difficult in a painting. Sometimes you have to hold your hands up and say, 'I have to use other media'. Maybe it's also an awakening in me. There are things I have enjoyed that never appeared in my work until more recently. It's about expanding my practice outwards at this mature point. I'm still looking to be surprised by what I do.

'Space Shuffle', Collective, 2024

Moyna Flannigan (b.1963)

Jennifer: Which artists and themes have inspired you over the years?

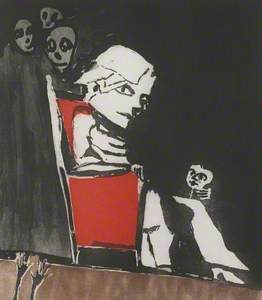

Moyna: For a long time, I was obsessed with Goya and his themes of power. He was the first artist, really, to produce works outside of official commissions, that were an imaginative response to the world he was living in. He was hugely innovative in that way.

I've always been interested in women who are mavericks in the art world. When I was at art school, painting was a very male thing. So a lot of women moved away from painting at that time into newer media without the associations. I chose to stay with painting, but started to look at it from the perspective of being a woman and what hadn't been said in painting. In recent years, I've been much more interested in women who may have started as painters – Louise Bourgeois, for instance – who gradually moved away from that and started, in fact, using materials which were non-art materials.

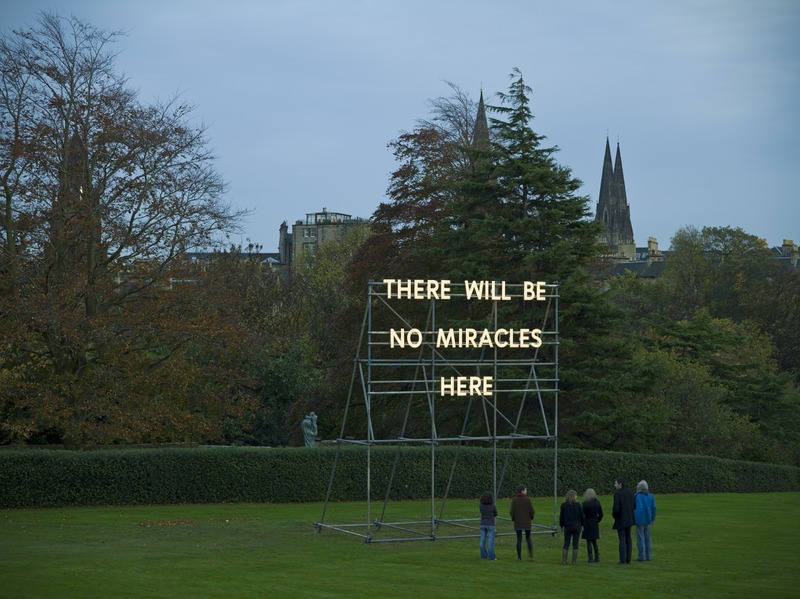

Jennifer: Can you tell me about your recent show, 'Space Shuffle' at Collective in Edinburgh?

Moyna: When I was asked to do it, they were keen that I responded to the observatory space because, as a painter, you would normally show in a white cube. This necessitates a different approach and I had been working in collage for some time and felt that I could somehow take the collages into space rather than work within the constraints of a rectangle. I had just been in a group show where I tried out a couple of suspended sculptures, and the sculptures are made from offcuts of the collages so, in a way, they're all part of the same process.

'Space Shuffle', Collective, 2024

Moyna Flannigan (b.1963)

The idea was to make a sort of constellation in response to the history of that building as an observatory; that was in my mind when I started out. It allowed me to make new work in new forms that I wouldn't necessarily have used. For instance, I work at Edinburgh College of Art and there's a classical frieze on the walls in the sculpture court: it just didn't seem appropriate to hang paintings in that space. I felt I had to come up with new forms and the frieze and the sculptural installations seemed more unusual. Although it's a very big space, I wanted to put quite delicate works in it because there's quite an atmosphere and I wanted to make something contemplative.

'Space Shuffle', Collective, 2024

Moyna Flannigan (b.1963)

Jennifer: Collective is celebrating its 40th year. You were an early member – how important are these kinds of organisations to artists, both now and then?

Moyna: I was a committee member and a board member in the 1990s and it had a huge impact on me. After Edinburgh College of Art, I had gone off to America for two and a half years – I did a master's at Yale – so when I came back, a lot of my peer group had moved on. I felt that I needed to re-engage with a peer group somehow. At that time, the art world was completely different, there just wasn't the same sort of gallery system, so there were public galleries that received public funding and then nothing, almost – certainly not in Scotland.

Collective is a kind of bridge for new graduates: it was absolutely crucial for learning how things worked in the art world. I joined almost 10 years after Collective started. It began to expand and become more established in terms of its funding. It was great to be involved in it at that time. They still have the Satellites development programme supporting young artists.

Jennifer: What other projects have you planned for the coming year and beyond?

Moyna: I've got a few things bubbling away, but sometimes an exhibition can be a full stop: you've got to start again. I don't feel so in this case, I feel like 'Space Shuffle' has opened up a whole set of ideas, which I now need to pursue in other ways. So I'm looking forward to that. I've started working on a couple of huge paintings, which have no particular destination at the moment. Sometimes you have to move out of your medium into a new medium to find out what is good about the medium you normally use: it's about reacting to what I've done and seeing how I can take it further.

Jennifer McLaren, freelance arts journalist based in Scotland

This content was funded by PF Charitable Trust