In the series 'Seven questions with...' Art UK speaks to some of the most exciting emerging and established artists working today.

Kaye Donachie (b.1970) wants to make a mood. Her dreamlike canvases may be rooted in reality, but they evoke fleeting thoughts and feelings rather than capturing a particular person or a fixed time and place. Working from archival photographs alongside the art and writing of the women of twentieth-century modernism, she creates what she calls 'cyphers of ideas and emotions'.

In paint, she conveys both an outer appearance and an inner experience; she's interested not only in the way we look, but how we feel. 'It's not just about the visual,' she tells me. 'The face needs to be a vehicle for something else.'

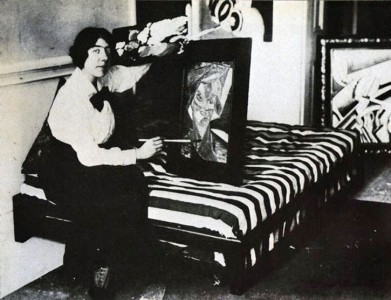

Kaye Donachie in her London studio

The Glasgow-born artist, who lives and works in London, grew up on a blustery clifftop in the seaside town of Lowestoft, the most easterly point in Britain. Despite the absence of an art scene, she believes that being on the fringes of the country shaped how she felt and saw things. As a child, she liked to draw, and her mother was encouraging. 'When I was young, she told me I could draw every day if I wanted to. I asked what that would make me, and she said, "An artist".'

Donachie went on to study in Birmingham before gaining an MA at the Royal College of Art from 1995 to 1997. Keen to avoid literal narratives, she painted mostly empty interiors, but she soon turned her attention to figures and faces, quasi-portraits rendered in similar muted shades of grey, midnight blue and rouge. Regardless of the subject matter, she aims to create images that unravel and reveal themselves slowly, that shift enticingly between past and present, and that draw you back again and again.

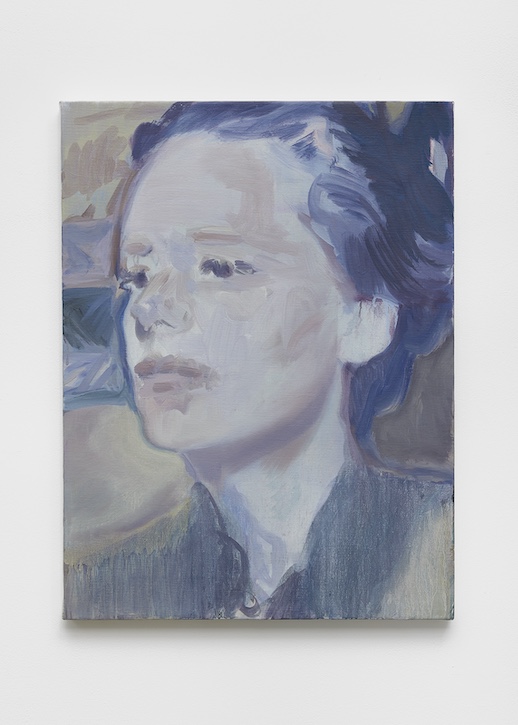

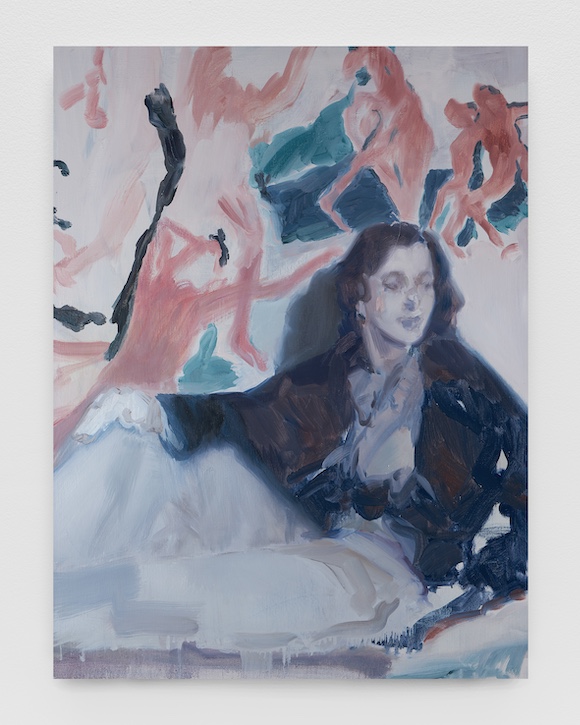

Caress of Metaphor

(2024), oil on linen by Kaye Donachie (b.1970)

Her recent exhibition at Maureen Paley, 'I kept the memory for myself', draws on the German painter Gabriele Münter, a founding member of Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider). It follows 'Song for the Last Act' at Pallant House Gallery last year – Donachie's first solo show at a UK museum – which included a selection of works from Pallant House's collection chosen by Donachie, by artists such as Walter Sickert, Pauline Boty and Jacqueline Morreau. I talked to Donachie about avant-garde women, fiction and being surprised by paint.

Chloë Ashby: What draws you to art-historical influences and sources?

Kaye Donachie: I think I've always been drawn to the past because I can see it in the present. I like how art from a certain time represents a mood or a cultural scene. The artists who I find most interesting have a generosity in their work; it's not completely finished.

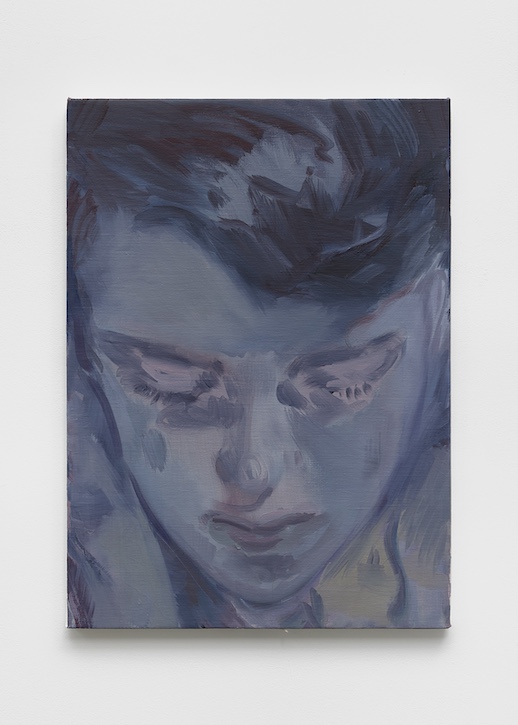

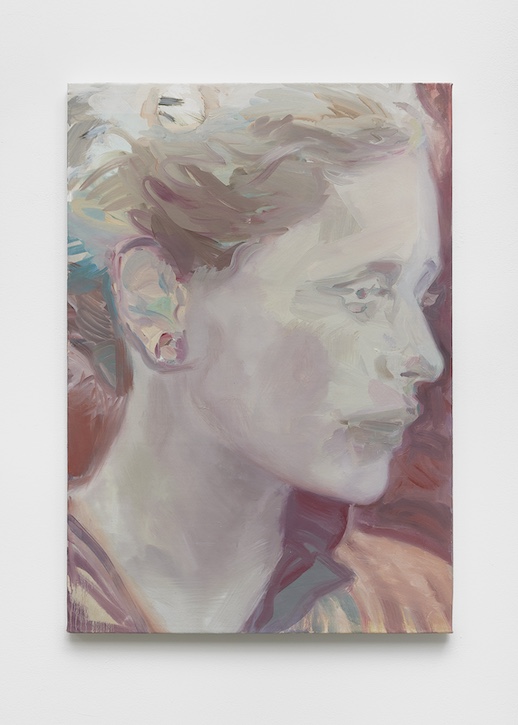

Occasional magic

(2024), oil on linen by Kaye Donachie (b.1970)

It's the same with history – I can take something and revise or reinterpret it for myself, and it becomes like fiction. I can be quite inventive. I'm looking for something that's an echo from the past but somehow relevant now. And I like that someone in thirty years might go back to that same period and take something different. There's a web of connections.

Chloë: How did you land on twentieth-century women – such as Claude Cahun, Nina Hamnett and Lee Miller – as your subjects?

Kaye: I find the turn of the century to be a fascinating point in history, culturally, because it's a time of flux. People were exploring and coming out of one way of living into another; there was a sense of freedom when it came to identity and sexuality. I've always been interested in communities on the periphery, and I started reading about the artists, writers, dancers, psychiatrists who came to live at Monte Verità in Ascona during the First World War.

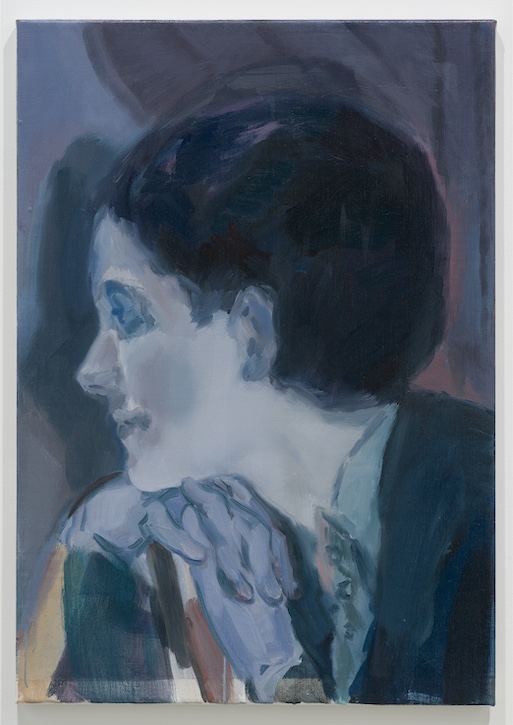

Notes shift

(2023), oil on linen by Kaye Donachie (b.1970)

The women, such as Emmy Hennings, were more interesting to me, partly because they had limited biographies. I realised that I could connect with their voices through their writing and their art. I think that's the point in history that works for me because it's vague enough for me to interpret things for myself – there's enough, but not enough.

Chloë: Tell me about your approach to painting faces. I'm curious if, by the time you're finished, you look at them and think of the women who inspired them, or whether they become something altogether more fictional?

Kaye: I have an archive of images and words – snippets and fragments of things I've read and seen. They might not have anything to do with a face, but it builds up a kind of frame. As I go along I might alter the composition or the colour or merge bits together. Obviously within the genre of portraiture they are faces, but when I'm constructing a composition it's not a representation of the person.

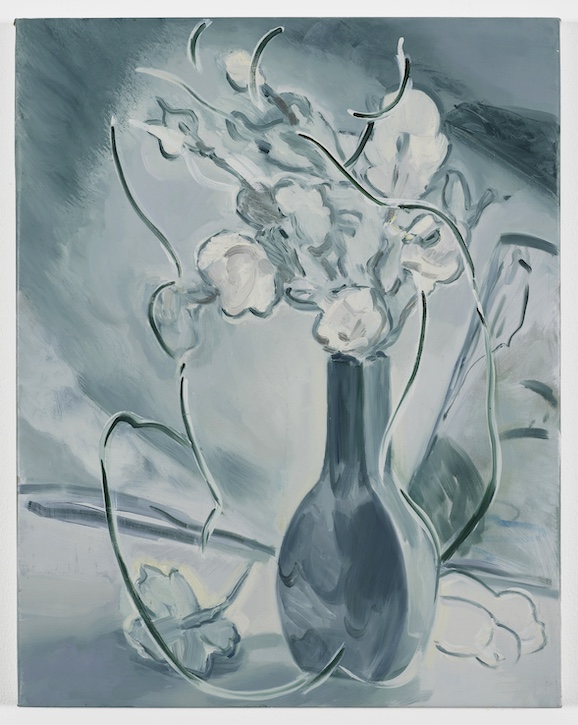

Inward Night

(2024), oil in linen by Kaye Donachie (b.1970)

They start off with some kind of realism because they're based on a person's biography, but I draw and make lots of studies, and by the time they're done they become my own person – I reclaim them as something of mine.

Because they're not literal representations of people, I don't really see them as portraits. It's not like someone has sat for me. I don't know their character. All I can go by is their art or their writing, and I get a sense of a feeling or a mood from that. And actually I think that's where the portrait is – it's more a grasping of an expression that comes through their art. Lots of them have a clear sense of their own identity, and I try to make them protagonists within a narrative that doesn't really exist.

Silence Sings

(2024), oil on linen by Kaye Donachie (b.1970)

Chloë: You also look to poetry and short stories, as with your most recent exhibition, 'I kept the memory for myself' at Maureen Paley, which draws on Virginia Woolf. Can you tell me about your relationship with writing?

Kaye: I think poetry is amazing – how someone can describe a tree in three words, and in a way I've never thought about. What I love is the leaving of space, not overstating things. I don't want someone telling me what to think or wrapping everything up, which is also how I feel about art.

Perishable Songs

(2024), oil on linen by Kaye Donachie (b.1970)

When a piece of text or a painting explains everything there's no room or need to revisit it, because it's all been said and there's nothing else to add, it's resolved so well. It's about having something that you can keep reinterpreting. That's what I love about poetry and short stories – the sense of continuity, the lack of a beginning and an end.

Roses Slumber

(2024), oil on linen by Kaye Donachie (b.1970)

Chloë: How do words help you conjure your portraits?

Kaye: For me, it's words more than images that help to set the emotion or the tone. I don't necessarily look at a photograph to give me a feeling; I find words do that, and then I can interpret it for myself through paint. I try to nod to the person through the titles, which often come from poetry. Meandering in bleared Forgetfulness (2023), for example, references the writings of Iris Tree, who is also depicted in Monotonous Remorse (2019).

Sometimes I'm not interested in a whole poem; it will just be a line, out of context, which slightly abstracts it. But it's a link, a sense of going back and pulling forward. They nod to where the works have come from without explicitly saying who they're depicting, because it's not like that.

Monotonous remorse

2019, oil on linen by Kaye Donachie (b.1970)

Chloë: What's the relationship between your portraits and the still lifes, interiors and landscapes you've painted?

We together

(2018), oil on linen by Kaye Donachie (b.1970)

Kaye: When I was at the Royal College of Art, just under twenty years ago, I made lots of paintings of interiors. I think of them as more poetic, dreamlike spaces, almost projections. I think it comes from growing up looking at the sea, which you could see from every room in our house.

I always thought of it as a sort of screen, not a deep space but a mental space that I could project things onto. And I think both my interiors and my faces are similar. They engage the viewer with the same kind of mental distance; they're sites of action and actors waiting to become activated in a way.

In a glass that mirrors me

(2010), oil on canvas by Kaye Donachie (b.1970)

Chloë: Finally, tell me about your relationship with paint itself, which in your work is visceral, sensual, somehow both familiar and strange.

Kaye: I'm drawn to paintings that have a wet-on-wet feeling, which look like they've just been made. It's the same with writing – I like it when you don't know where it's come from, it feels conjured up rather than over-egged.

In my own work, I'm always searching for the moment when something feels like it's been made in one breath, when it has a lightness to it. I don't want it to feel overworked or self-conscious. I like there to be a sense that the edges are moving rather than blocking each other in, and that both the background and the foreground are active.

Untitled

(2024), framed monotype on paper by Kaye Donachie (b.1970)

It's important for me to go through the process of making lots of studies, and then not to think about it when I'm working on the final image. There's a freedom within that way of painting. In the end, I want it to surprise me.

Chloë Ashby, freelance writer and author

'I kept the memory for myself' at Maureen Paley, London, runs until 30th March 2024.

This content was supported by Jerwood Foundation