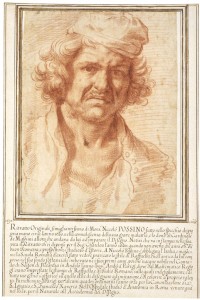

In Nicolas Poussin's Eucharist (c.1637–1640), twelve disciples lie on a Roman triclinium, or padded couch, surrounding plates of broken bread and a cooked paschal lamb. In the painting acquired by the National Gallery, London, right before Easter, all but two gaze intently at Jesus who lifts a piece of bread and goblet of wine with his left hand and makes a sign of benediction with his right. Judas – who will betray him for 30 pieces of silver – faces the viewer, while John the Baptist leans against Jesus, appearing fast asleep.

Poussin's work is one of a seven-part sacrament series – including Baptism, Penance, Eucharist, Confirmation, Marriage, Ordination and Extreme Unction – which was created for his patron, the Roman antiquarian Cassiano dal Pozzo in the late 1630s.

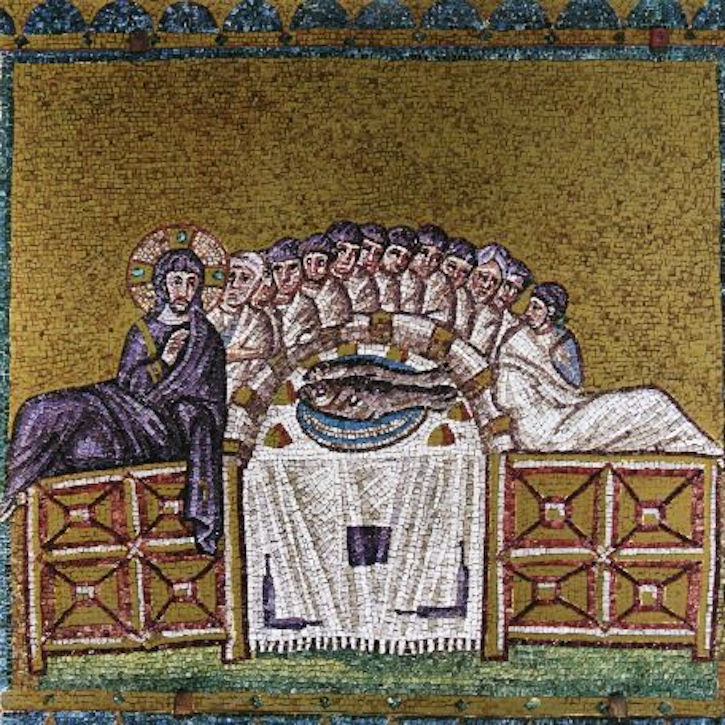

Poussin was a Classicist, and this painting references much older depictions of the Last Supper in the Roman catacombs. In these depictions, Jesus and his apostles sit on a semi-circular triclinium surrounding two cooked fish – an alternative meal common in Mediterranean depictions.

Mosaic of the Last Supper

sixth century, Basilica of Sant'Apollinare Nuovo

At first glance, Eucharist seems like a stereotypical Last Supper painting, but on closer inspection, it tells the story of how artists reinvented the popular scene of Jesus's final meal over and over again.

Poussin's painting situates the Biblical group in a windowless room with Roman doric columns outlined against the back wall by a double wicked lamp, catering to the Roman fascination of his patron. But Poussin's depiction is strikingly different from late Antiquity and early Medieval versions of the Last Supper that place it within the visual life of Jesus or preceding the Stations of the Cross. Poussin embeds the Last Supper in a series of sacraments instituted by Jesus and opts for the less popular depiction of the shared meal.

Sketch for ‘The Last Supper’, St Mary's, Weymouth

1719–1720

James Thornhill (1675/1676–1734)

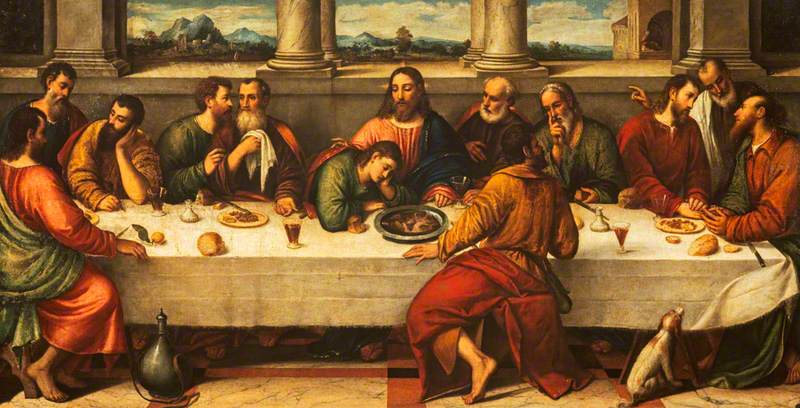

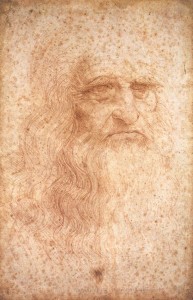

The Last Supper is usually depicted in one of four scenes – the Betrayal (Jesus announcing that someone would betray him), the Eucharist (Jesus consecrating the Eucharist in front of his apostles), the Foot Washing, and Farewell. The Betrayal is the most common and well known from Leonardo da Vinci's Last Supper (1495–1498). A copy produced by Giampietrino in the Royal Academy of Arts, London, witnesses the disciples recoil in disgust and question each other upon hearing that one of them would betray Jesus, while Judas stealthily reaches for a plate of silver.

The Last Supper

(copy after Leonardo da Vinci) c.1520

Giampietrino (active 1500–1550)

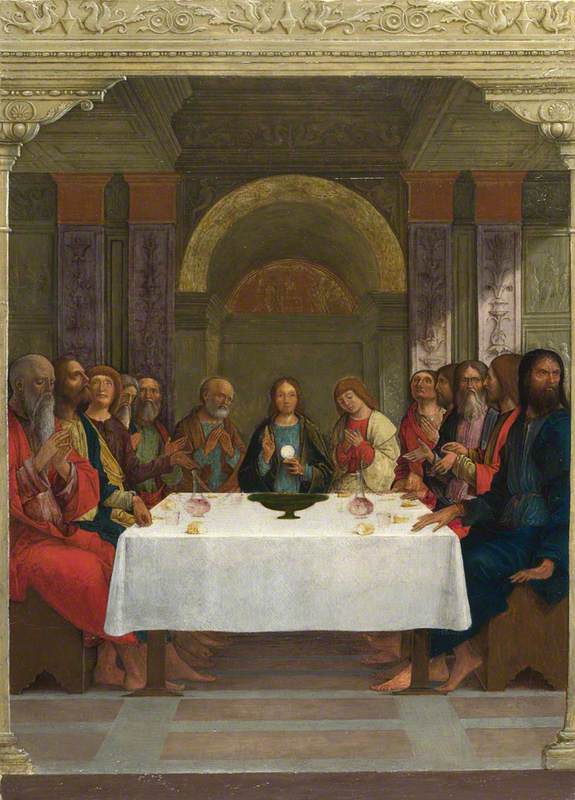

Poussin's depiction of the Eucharist scene was common in early Christian imagery through the Byzantine Era before disappearing. It reappeared in the fourteenth century, with an air of mysticism. Sometimes in early Christian and Eastern Orthodox depictions of the Eucharist scene, also known by art historians as the Communion of the Apostles, the disciples would gather around Jesus or in a line to receive the host. Jesus feeds the apostles in The Last Supper; a Night Piece at the University of Oxford's Christ Church.

The Last Supper; a Night Piece

1550–1600

Italian (Venetian) School

This body language reinforces the basis for the sacrament of Communion in the Christian Church, and the scene has been added as Biblical evidence for this tradition on tabernacle doors. Ercole de' Roberti's The Institution of the Eucharist (probably 1490s) was a panel of a predella – the lowest part of the altarpiece – and its keyhole indicates it was the door to a tabernacle, or box which held the consecrated bread and wine when not on the altar. Poussin's painting is far more intimate, likely for personal viewing in a home. This style reflects how the artist personally avoided large altarpieces made for the public.

The Institution of the Eucharist

probably 1490s

Ercole de' Roberti (c.1455–1496)

But Poussin's painting does follow several important conventions. In Eucharist, Jesus appears in red and blue. This red colour – Jesus is the only figure wearing intense crimson compared to the other disciples who wear darker and lighter shades of orange – represents his impending passion; the blue – worn by four other apostles at the table – is usually reserved for royalty because of rarity; it comes from ultramarine derived from lapis lazuli.

Moira Doggett takes this one step further in her twentieth-century Last Supper, replacing the twelve disciples with twelve monarchs of England and Wessex, including Queens Elizabeth I and Elizabeth II seated at Christ's right hand.

Writer Peggy Orenstein argues that in art history, red and blue denote the relationship between Mary and Jesus. In religious art, Mary is traditionally depicted in blue, while Jesus appears in red. Thus, this colour distinction complicates the most well-known depiction – Da Vinci's Last Supper, which presents John and Jesus wearing inverses of the same red and blue colours.

Anglican priest Paul Oestreicher suggests that this intimacy and Jesus's pivotal last words may indicate a deeper relationship between the Baptist and Jesus, with some scholars even connecting this queer iconography to its gay painter. These theories draw on some of Jesus's last words on the cross in which he connected Mary and John as family. He told Mary, his mother, 'Woman, behold your son,' referring to John, and to John, 'Behold your mother.'

In the Eucharist, John also appears laying on Jesus's lap, possibly asleep, and modern artists such as Barry Brandon (@thequeerindigo) are reimagining the Last Supper with queer disciples. Swedish photographer Elisabeth Ohlson Wallin does something similar in her 1998 Last Supper piece titled Nattvarden, in which Jesus wears heels and is surrounded by apostles in drag.

Colour is thus imbued with deeper meaning, as many modern depictions wrap Jesus in white garments, a symbol of purity that was associated with growing Social Purity Movements in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. This image of a Jesus in white persists largely to this day.

The Last Supper

early 19th C–mid-19th C

unknown artist

John's position in Poussin's Eucharist, of sleeping or laying on the bosom of Jesus to his right, is one of intense devotion and supplication, although sometimes the beloved appears on his left to give viewers the impression that he is seated on Jesus's right. In The Last Supper from the Church of St George in Antwerp, John is sprawled over the table, with Jesus extending his arms on either side of the sleeping apostle. Following tradition, the table in this Last Supper also contains the paschal lamb, creating a visual mirror for a sleeping John; traditionally this lamb serves as a mirror for Jesus, who sacrifices himself for humanity's salvation.

The Last Supper (from the Church of St George, Antwerp)

late 15th C–early 16th C

unknown artist

Similarly, Poussin's Eucharist contains a visually distinct Judas, although without his signature bag or plate of silver, which he traded with Roman authorities in exchange for Jesus. In Da Vinci's Last Supper, Judas reaches for a dish of silver. Judas is often depicted holding this money in a bag or the bag is tied around his waist, visible only to viewers when he is seated on the opposite side of the table from Jesus.

From the introduction of the oblong table, most depictions situated all figures on the opposite side of the table but a few break with tradition, placing Jesus across from Judas. Judas's back is symbolically facing us in Bonifazio de' Pitati's innterpretation. In preliminary drawings made for a triptych mural depicting the Last Supper, twentieth-century South African artist Cecil Skotnes also places Judas too far away to reach the bread and wine – two symbols that Christians believe become or represent the body and blood of Jesus and thus the path to salvation.

Just as the orientation of the table changes over time – semicircular, U-shaped, oblong, angled – so does the meal on the table and the people who sit there. As the Last Supper depicts Jesus and the apostles at Passover, Poussin's Eucharist presents a prepared paschal lamb. In late Roman and Byzantine depictions, however, fish was the main course. Similarly, Last Suppers created before 1500 feature unleavened bread; after this point, artists such as Poussin switched to historically inaccurate leavened bread. From the sixteenth century onwards, torn bread changed to flat wafers incised with a cross, a direct link to contemporary communion wafers. Over time, portion sizes also increased.

Each Last Supper painting is a reinterpretation – a reimagining – of an older variant. Just as Poussin's Eucharist references ancient Roman catacomb versions where Jesus and his apostles are seated around a semi-circular triclinium, so too does Stanley Spencer situate the apostles around a triclinium.

John the Baptist leans against Jesus's chest, and the dinner takes place inside, but Spencer places the party in a claustrophobic brick room whose window throws off the painting's symmetry. It's just one example of how pre-nineteenth-century Last Suppers ripple through contemporary depictions of the holy meal.

Emma Cieslik, religious scholar, museum professional and writer

This content was funded by the Samuel H. Kress Foundation