Self portraiture can provide a fascinating glimpse into an artist's personality, their private life or professional ambition and social success.

In a similar way to portraits, self portraits are wonderfully varied. Some are playful and innovative, going against visual traditions established by earlier generations of artists, whilst many adopt an image of the artist at work accompanied by their tools or objects suggestive of their status, as an act of self-promotion. Most commonly, artists paint themselves to practise and improve their ability to create lifelike portraits, to attract potential clients or achieve acceptance from peers.

Read on to see how artists of the eighteenth century used their own image to celebrate or publicise a particular moment, milestone or achievement in their life and career.

Godfrey Kneller

During the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, England became home to an international community of artists. Attracted by the ever-growing interest of the middle classes in owning art, artists began acting more like entrepreneurs, conjuring up new ways of documenting the people and world around them, and reaching new audiences through engraved reproductions of their work.

The German-born portraitist Godfrey Kneller (1646–1723) spent most of his career in England. There, he was made court painter to James II and George I, and principal painter to William and Mary – positions of dominance over his fellow artists that spanned several decades.

This rather unusual self portrait is also a double portrait: John Smith (1652–1743), the printmaker, holds an engraved image that he has made from Kneller's self portrait of 1694. Kneller gave this painting to Smith as a gesture of friendship. The professional alliance certainly benefitted both artists. For Kneller, Smith's many printed copies of his portraits widely publicised his work. For Smith, this secured his reputation with collectors in London and on the continent. To show his gratitude, Smith signed his copy of this painting as Kneller's 'most humble servant'.

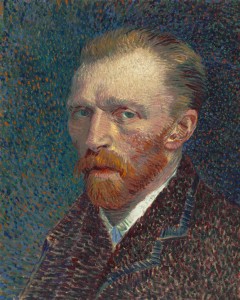

Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun

Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun (1755–1842) painted close to 40 self portraits during her career and whilst many show her in the act of painting, in a handful of them she affectionately embraces her daughter, Julie. Created in the years following her swift departure from France at the onset of the French Revolution (1789–1799), Vigée Le Brun presents herself as a self-assured and accomplished artist as well as a doting mother. Here she pauses momentarily from painting her daughter's portrait.

While in Rome, one of the first cities she lived in during her 12-year exile from France (1789–1802), Vigée Le Brun produced several versions of this image. In the original version, she has partially finished a portrait of Marie Antoinette, her Queen and once close friend and loyal patron, who at that time, was being driven from power by the French revolutionaries.

A self portrait may represent an exercise in technique or personal self-examination, or simply function as a calling card. We may never fully know the motivation behind these eighteenth-century self portraits, but as a record of some of the world's greatest practitioners, they offer an invaluable record for us and a window into the artist's life.

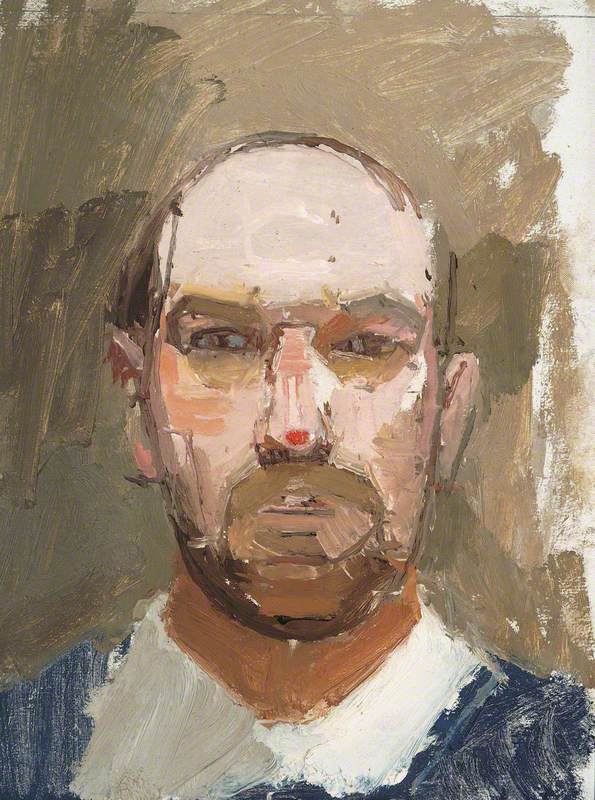

Alexis Grimou

Working in Paris during the early eighteenth century, Alexis Grimou (1678–1733) painted numerous drinking portraits of himself and his elite clientele – a nod to jovial tavern scenes commonly found in Dutch and Flemish seventeenth-century art.

Grimou's soft smile and relaxed body language welcome us into this scene of merriment. His plump, rosy cheeks and heart-shaped face have similarities with his other known self portraits. A raised wine glass in one hand and decanter grasped in the other perhaps replace the brush and palette which Grimou saw when he looked in the mirror. The artist's creativity with oil paint is captivating – look at the expertly layered strokes of white paint on the ruffled collar and cuff nearest to us, the reflections in his eyes and the gleam on the glassware. This exquisite detail definitely adds to the atmosphere as does the warm lighting, which creates a glowing aura around him.

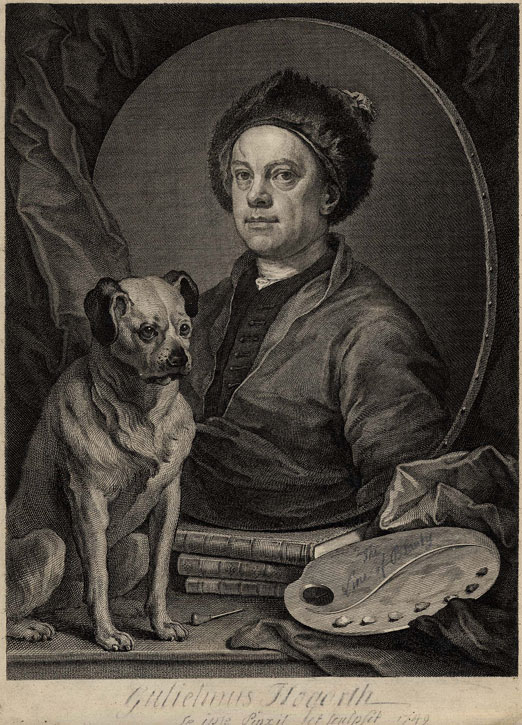

William Hogarth

For William Hogarth (1697–1764), it was the engravings after his paintings rather than the paintings themselves that secured his fame and financial security. During his early career, he trained as an engraver and went on to produce print versions of his most popular paintings, which sold widely at home and abroad.

In this painting, Hogarth has his image resting on the books of three giants of English literature – Shakespeare, Milton and Swift. These authors provided inspiration for Hogarth's satirical series, the most famous being A Harlot's Progress (1732) and A Rake's Progress (1735), both of which were produced as paintings and engravings. Hogarth's engraved image of this painting was attached to bound copies of his work as a kind of visual business card. In the reproduction he added an engraver's tool in the foreground, which an x-ray has revealed originally lay on the pile of books in this painting and was later painted over.

Gulielmus Hogarth

1749, etching & engraving by William Hogarth (1697–1764)

In 1753 he published The Analysis of Beauty in which he promoted the importance of observing life and movement, symbolised here by the serpentine line inscribed into the palette. Hogarth's devoted companion, a little pug called Trump, serves as an emblem of the artist's notoriously pugnacious character.

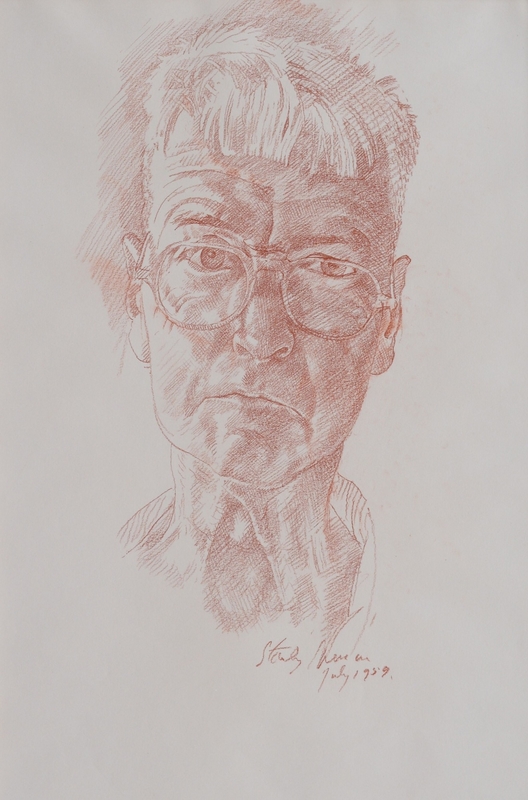

Johann Zoffany

The German painter Johann Zoffany (1733–1810) spent much of his career in England and painted this self portrait shortly after his arrival in 1760. During this time, he was employed by the famous actor David Garrick to provide visual records of his theatrical triumphs. In this highly original self portrait, Zoffany exudes a stage-like presence. A warm light captures his pensive expression, with his face angled away from us creating a shadow across his jawline, and illuminates his slender hand, which rests on a portfolio and loosely grips a 'porte-crayon' containing charcoal.

Zoffany was best known for painting 'conversation pieces' showing intimate group portraits of friends or family, often outdoors.

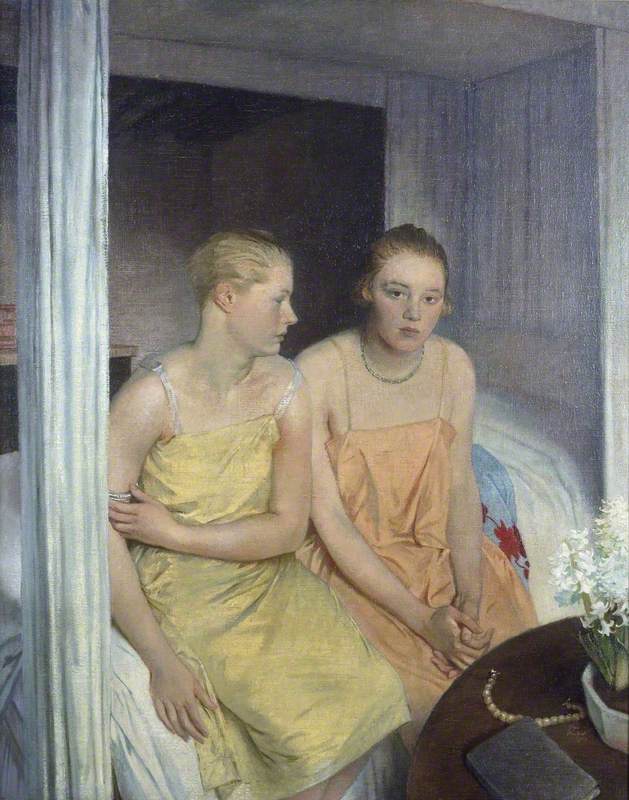

Angelica Kauffmann

The eighteenth century saw the arrival of a generation of female artists determined to establish their position in the traditionally male-dominated field of painting. Painted when Angelica Kauffmann (1741–1807) was in her 50s, this work shows her younger self faced with the dilemma of pursuing a career either in painting or music. Ambitious and well-connected through her artist father, the Swiss-born artist became a sought-after painter of historical subjects and portraiture in England.

Self Portrait of the Artist Hesitating between the Arts of Music and Painting

1794

Angelica Kauffmann (1741–1807)

Angelica was one of only two women – the other being English flower painter Mary Moser (1744–1819) – among the 34 original members of the Royal Academy. No other female artists became Academicians until the early twentieth century. In another self portrait, now at Kenwood House, Kauffman appears as the personification of Design – the practice of drawing and the study of classical art and the ancient world was a major part of an Academician's training.

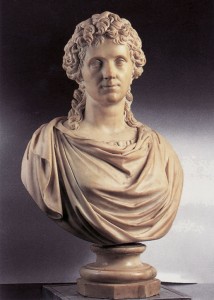

Joshua Reynolds

Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792) painted around 30 self portraits throughout his career and this painting shows him at the height of his achievements. Arguably the greatest English portrait painter of the eighteenth century, Reynolds became the first President of the Royal Academy of Art when it was founded in 1768.

Painted around a decade later, this work celebrates his position as an intellectual and artist: he wears the robes of his honorary doctorate from Oxford University and rests a hand on a bust of his Renaissance hero, Michelangelo. Reynolds' lectures to the Academy's students, published as Discourses on Art, promoted the study of classical and Renaissance art. During the second half of the eighteenth century, Reynolds became the leading painter of the 'grand portrait', with sitters often standing in classical poses and accompanied by settings and accessories that conveyed their status.

Thomas Gainsborough

This is the earliest known self portrait by Thomas Gainsborough (1727–1788) and one that shows him as a family man. He married young, when he was only 19. The painting is unfinished – notice his wife's left hand – and many changes have been made by the artist, suggesting that this work was an opportunity to practise poses, clothing, and the background landscape.

Portrait of the Artist with his Wife and Daughter

about 1748

Thomas Gainsborough (1727–1788)

During the 1750s Gainsborough built a successful business as a landscape and portrait painter in his native Suffolk and later in Bath. As a young painter he was especially admired for combining sentimental portraits of his rural clientele with the picturesque outdoors. Even in Gainsborough's 'grand portraits' the landscape background is given equal attention – it was his originality and skill that made him Reynolds' main rival in London during the 1770s and 1780s.

Tamsin Lee-Woolfe, freelance writer