Guildhall Art Gallery’s latest exhibition, 'Seen and Heard: Victorian Children in the Frame', features paintings of Victorian children, taken primarily from the City of London’s permanent collections. It also features key loans from major London collections, including Tate Britain, the Royal Academy of Arts, and the Museum of London, as well as works from further afield, including Falmouth Art Gallery, Cartwright Hall Art Gallery (Bradford), Walker Art Gallery (Liverpool), and Williamson Art Gallery & Museum (Wirral).

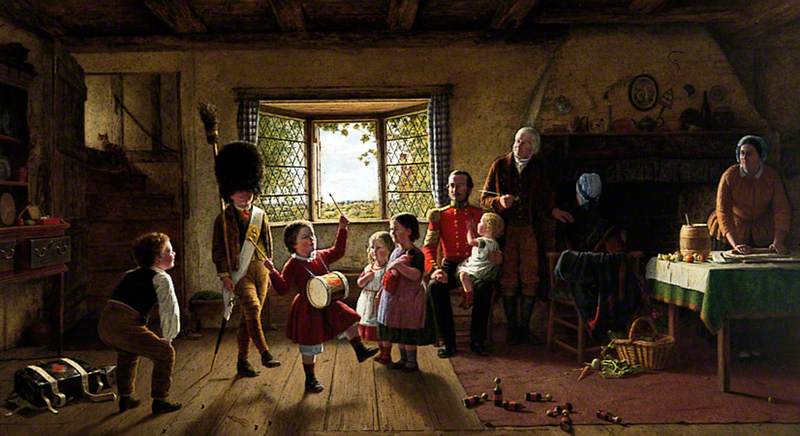

A blend of social and art history, the show aims to engage families and young people with fine art, as well as exploring how children and childhood were represented in paintings in the nineteenth century – a time of crucial social and artistic change, when the concept of childhood itself was being formulated as a special time of life.

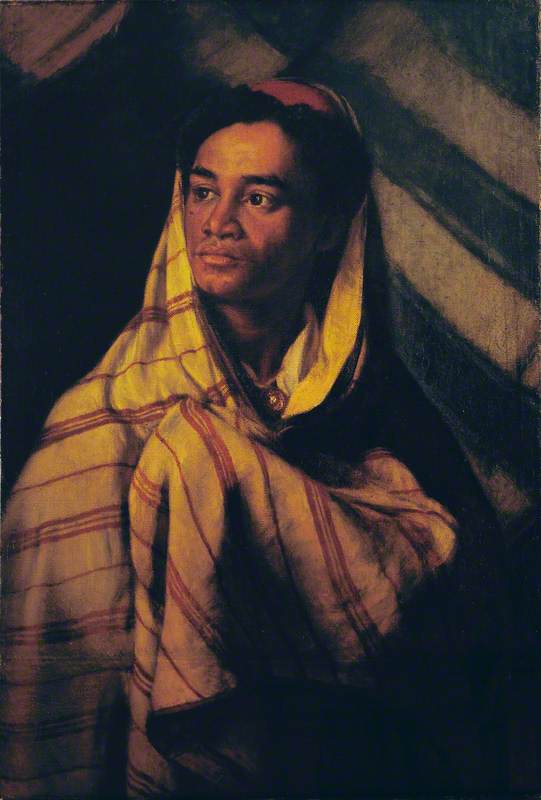

Threaded throughout are audience-appropriate discussions of how gender and morality are depicted, and reflection upon the Victorian interest in the subjective experiences of people from all walks of life.

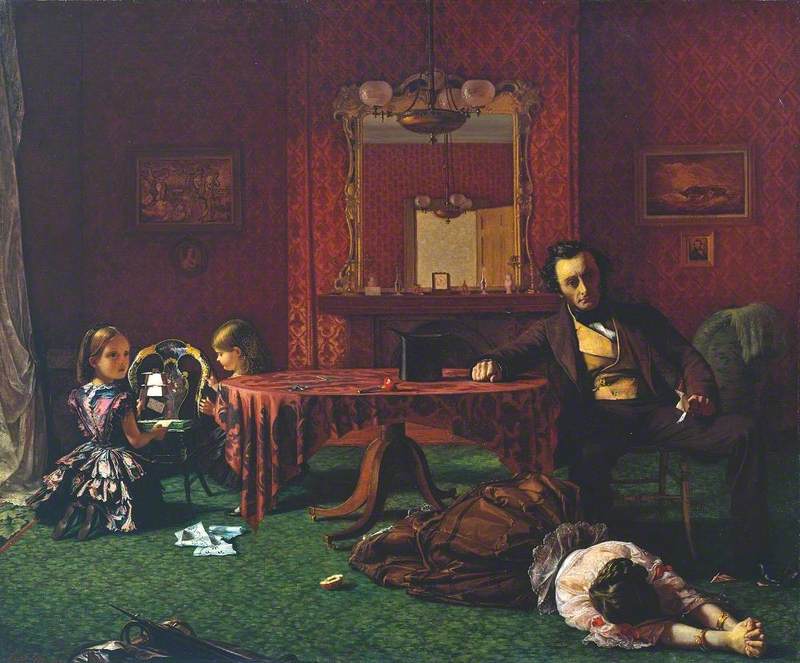

Though the genre is often associated with pure sentimentality, many of the works reveal a focus on complex emotion. Victorian artists engaged the sympathies of their contemporary viewers, asking them to encounter young people as individuals with an inner life of their own, deserving of respect and consideration.

This is particularly apparent in the depiction of children in poverty or in menial jobs. A comfortable middle-class audience was confronted with images such as Thomas Benjamin Kennington’s Orphans, and its power still resonates today.

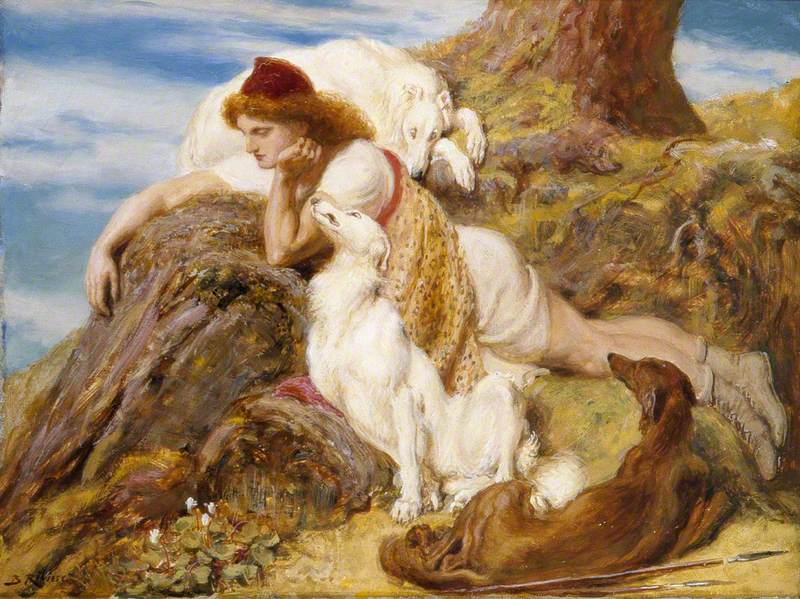

Remembering Joys That Have Passed Away

1873

Augustus Edwin Mulready (1844–1905)

Mulready’s Remembering Joys That Have Passed Away captures the impossibility of an innocent childhood for those in destitution, where danger lurks in the colonnades of the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane.

The exhibition includes accessible text panels for children, designed to generate intergenerational discussion on the parallels between past and present, and the effects of past culture on the social norms of today.

Modern children have unlimited access to images of themselves and exist in a technological landscape where very little goes undocumented. 'Seen and Heard...' encourages them to consider a world in which most children had no images of themselves.

A timeline tracks the progress of political and social reform, where successive Acts of Parliament gradually reduced working hours for children and eventually made education compulsory. Our own children attend school rather than a workplace because of legislative changes made by our Victorian forebears – children’s leisure time and legal rights were fought for (and won) in this period.

Political change was possible because of a greater, more widespread understanding of children as separate from adults, in need of protection from exploitation and degradation. The Age of Reform was also an Age of Feeling.

There are a few unexpected depictions among the work on display. Victorian children can be seen behaving in atypical ways. There are sensitive, thoughtful little boys, far from the masculine ideals we might assume, and rather un-demure little girls – boisterous, slothful, and a bit naughty.

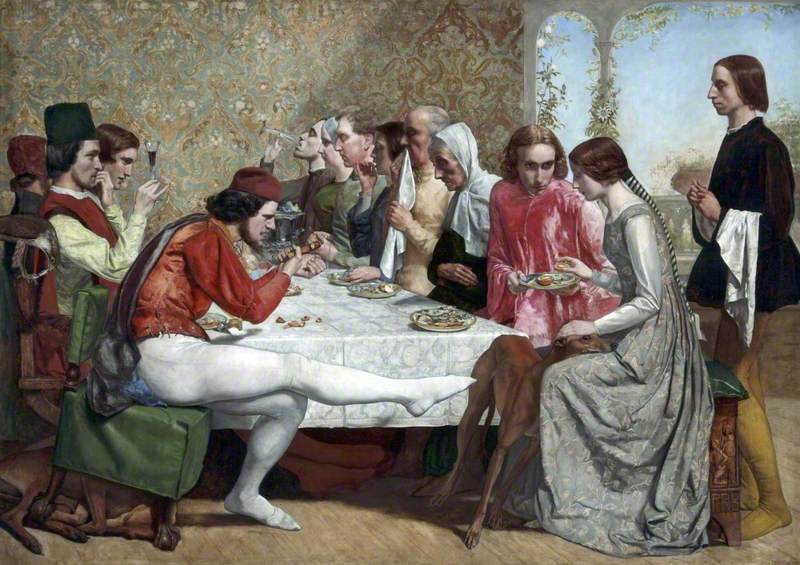

If Victorian cultural production could be said to unify around a theme, that theme might be an acute awareness of the gap between ideals and reality. This applies to the

John Everett Millais’ ever-popular paintings of his daughter Effie – My First Sermon (1863) and My Second Sermon (1864) – are as recognisable to parents now as they were for Victorian parents. We might wish for our friends to gaze in wonder at our neat and attentive children, but, dishevelled and bored, they have a habit of showing us up.

The final part of the exhibition is devoted to a family room, in which children and adults can read classic literature of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, try on Victorian costumes, create their own artworks inspired by the pictures, or simply sit and discuss what they have seen and heard.

Katty Pearce, Curator, Guildhall Art Gallery

'Seen and Heard: Victorian Children in the Frame' is on display from 23rd November 2018 to 28th April 2019 at London's Guildhall Art Gallery