Thinking back to my eclectic musical childhood, I remember a couple of Ladybird books – two volumes of The Lives of the Great Composers. Music history was for a long time taught this way – that great men (and it was always men) composed great works, and we should listen to them and venerate them as part of the canon.

While teaching has moved on, there is still a hangover of this in the pieces of classical music that are performed up and down the country, from the Proms to local amateur music-making. It's changing, but slowly.

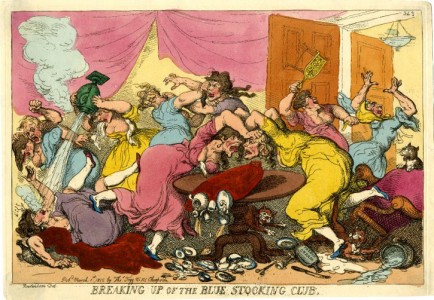

This hangover is perhaps even more marked in the music-related visual art adorning our national collections. In conservatoires and colleges, you will find endless marble busts of 'dead white men' as examples of something to aspire to – certainly in terms of composition. There are busts of women, but they tend to be of patrons or singers, like this one of Giulia Grisi as Bellini's Norma.

Giulia Grisi (1811–1869) in the Title Role of Bellini's 'Norma'

1851

Angelo Francesco Bezzi (c.1811–1867)

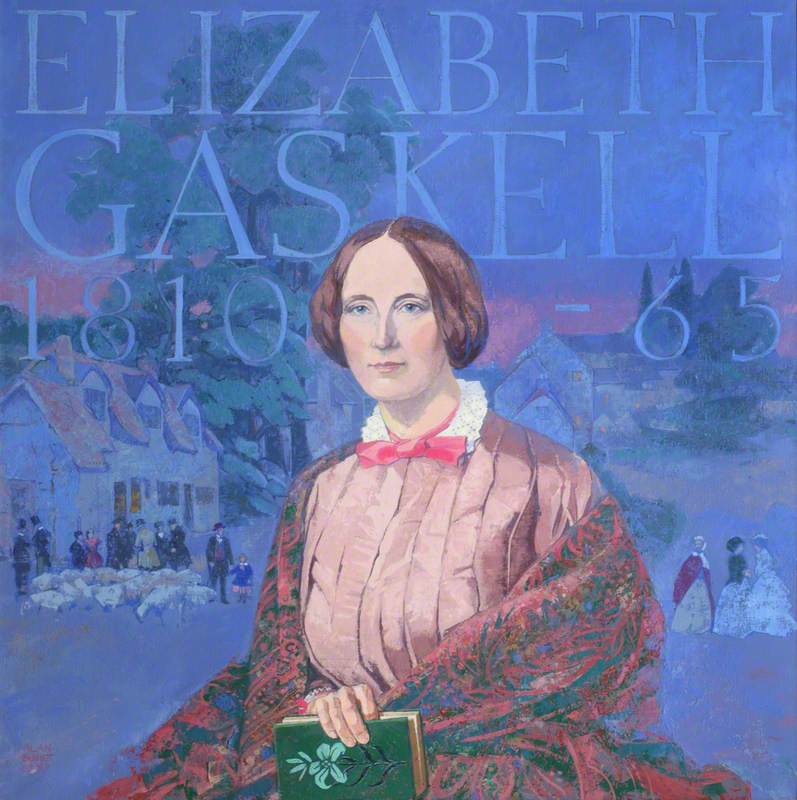

There are very few female composers immortalised in sculpture, and this is a reflection of how European society of the time viewed what was 'a suitable job for a woman'. As in literature, where the Brontës, George Eliot and Jane Austen wrote under male pen names, the same was true in music – Clara Schumann and Fanny Mendelssohn being notable nineteenth-century examples.

This is also not to say that the men didn't write fabulous music – their well-aired works are full of invention and delight and it's a pleasure to listen to them. We don't need to bin them all and stop listening to Bach and Beethoven.

What we can do is to note that these works are not the whole picture, and that they never were. Today we can look and listen again with fresh eyes and ears, listen to the counterpoint, and revel in the sheer richness of our shared musical history.

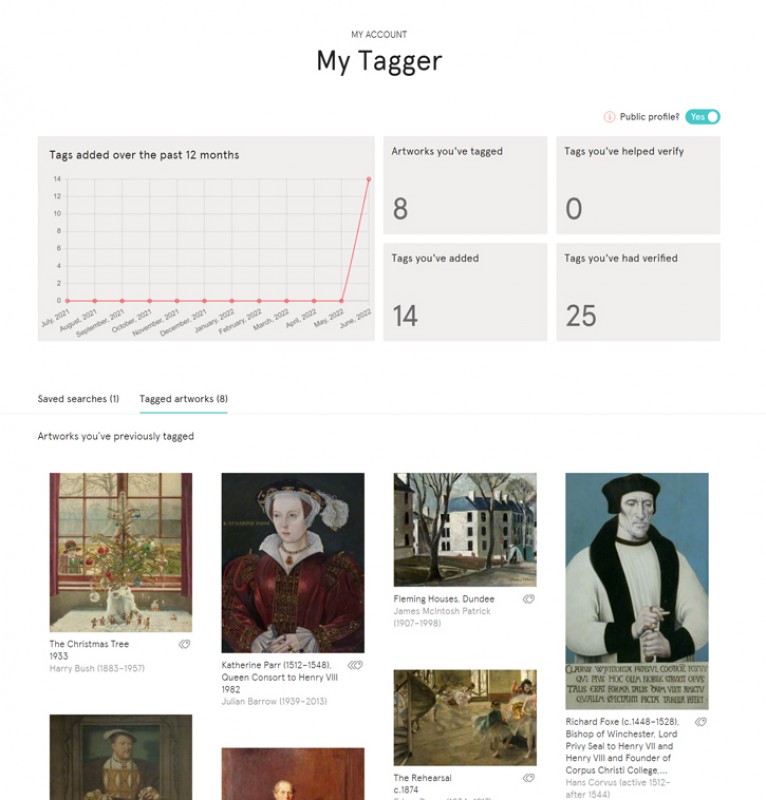

Which brings us to the list of composers. Here's a quick rundown of 14 male composers – and one woman – you'll find on Art UK in sculptural form.

Baroque beginnings

Henry Purcell (1659–1695) is the first English composer of note whose works are still widely performed today. This is largely due to a significant musical shift in the Baroque period (loosely 1600 to 1750) that included the development of equal temperament and the establishment of modern orchestral instruments. It meant that what was written around this time could still be reasonably accurately played on modern instruments today.

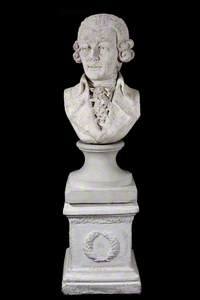

Purcell wrote a vast number of songs, odes and operas, including the very famous Dido and Aeneas. He is portrayed here in a modern sculpture with his usual wig.

George Frideric Handel (1685–1759)

c.1739

Louis François Roubiliac (1695/1702–1762)

George Frideric Handel (1685–1759) was born in Halle in Germany, but he moved to London in 1712, just before his former master, the king of Hanover, followed him over to become George I. Handel's music found instant success in his adopted country. His operas and oratorios thrilled audiences up and down the land, and his Messiah has become ubiquitous, particularly at Christmas. He became a key player in London life, and his house is now a museum. This bust is by the renowned sculptor Roubiliac.

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) was a prolific composer in almost all the popular styles of the late Baroque. He wrote a huge amount of organ and keyboard music, scores of cantatas for secular and sacred occasions, and orchestral and chamber music. He is also well known for having many children, several of whom also became musicians. His son Johann Christian Bach was known as 'the London Bach' and was painted by Thomas Gainsborough.

A classical quartet

Franz Joseph Haydn (1732–1809)

1893

Sidney Walter Elmes & Son (active c.1890–1940)

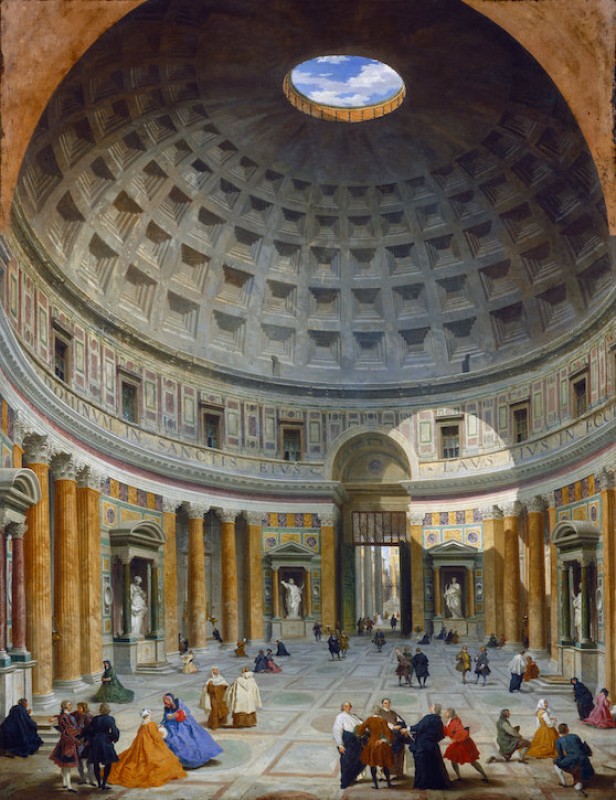

Franz Joseph Haydn (1732–1809) was the major figure in the move to the Classical style (the period refers to around 1750 to 1820, but there's no real consensus on when it starts and ends). The name 'Classical' is taken from the style in other arts and architecture that became fashionable in the mid-eighteenth century.

Haydn wrote over a hundred symphonies, essentially defining the form with his output. He also wrote keyboard sonatas, choral works, operas and string quartets, also virtually inventing the genre. His visits to London meant that he was popular in Britain, and remained so after his death.

What can be said about Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791) that you don't know already? He was a child prodigy, and wrote operas (including The Marriage of Figaro, Don Giovanni and Cosi fan tutte), symphonies, string quartets, concertos, choral music, keyboard sonatas – all in the most glorious fashion. Maybe you knew that he visited London aged eight, and wrote a motet (God is our Refuge, K. 20) that he dedicated to the British Museum? Maybe you didn't!

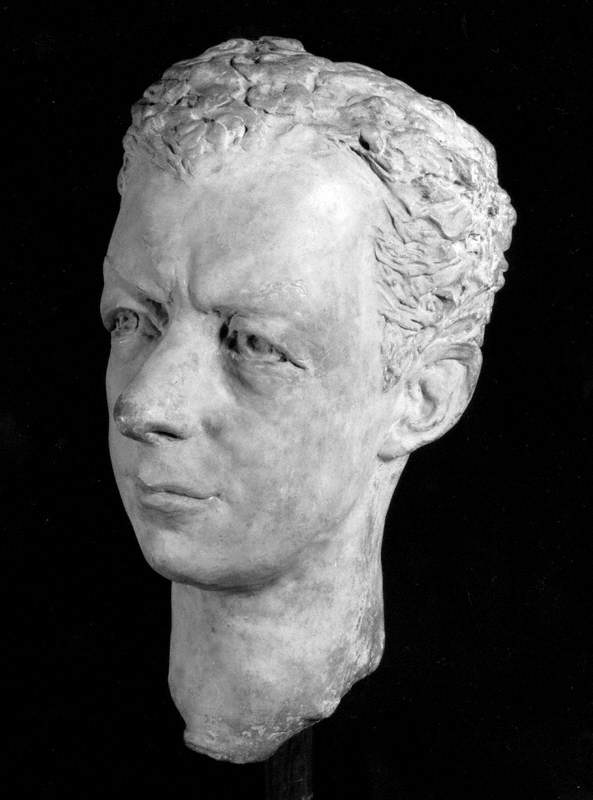

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827) was born in Bonn in Germany. He is very well-represented in the UK's sculpture collection – his stern face in white marble is almost the epitome of any composer bust you might have on a piano. Beethoven wrote new and exciting music, showing the world a new direction. His remarkable nine symphonies transformed the form into something way beyond those of Haydn and Mozart – the Third ('Eroica') was originally dedicated to Napoleon, the Fifth contains perhaps the most iconic four notes in all classical music ('fate knocking on the door'), and the Ninth features a choir crashing in on the final movement with an Ode to Joy.

Throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Beethoven was revered and often held up as the trailblazer for a new kind of composer – one who didn't have to work for a patron as those before him had done, but one who wrote music for its own sake. His piano sonatas and string quartets also remain core repertoire pieces, 250 years since his birth.

Franz Schubert (1797–1828) completes our quartet of 'Classical' composers. Sometimes Beethoven and Schubert can be seen as a bridge between Classicism and the Romanticism that was to dominate the rest of the nineteenth century. Schubert would often employ more unusual harmonic progressions than Haydn or Mozart, but his works remain largely Classical in nature. He is remembered today for his hundreds of Lieder – song settings of poems, usually in German – as well as his piano works and symphonies (his most famous, his Eighth, is known as the Unfinished Symphony).

Romantic revolutionaries

The very early nineteenth century was dominated by the likes of Beethoven, but soon gave way to 'the Romantic generation' – a group of composers who were all born around 1810.

Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (1809–1847)

1850

Ernst Friedrich August Rietschel (1804–1861)

Felix Mendelssohn (1809–1847) was a German composer born into a Jewish family, but he converted to Christianity aged seven. His best-known works include his music for A Midsummer Night's Dream, his Italian and Scottish Symphonies, the oratorio Elijah, and his solo piano works Lieder ohne Worte (Songs Without Words). He also wrote the melody to the Christmas carol Hark! The Herald Angels Sing and revived interest in the music of J. S. Bach with a performance of the St Matthew Passion in 1829. He went out of fashion during his own lifetime, but has since been reappraised and is today one of the most popular early Romantics.

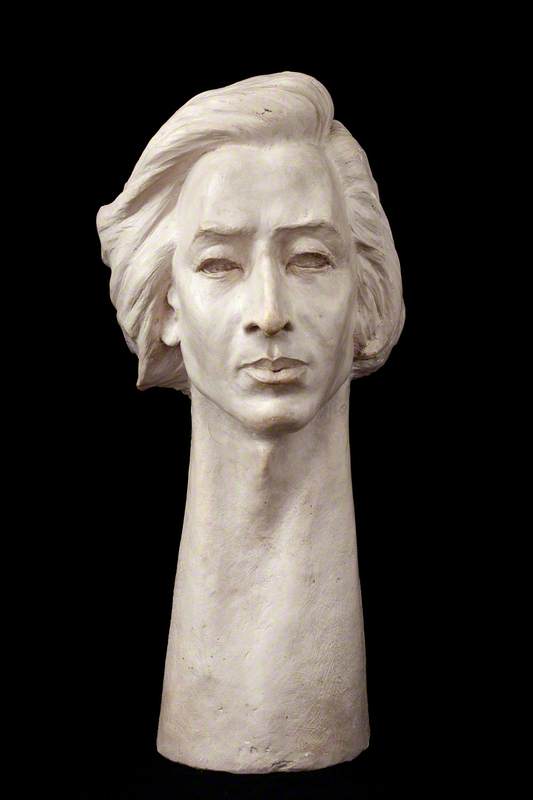

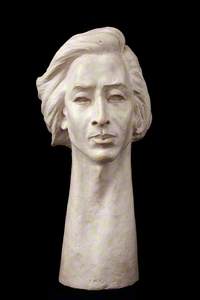

Polish composer Frederic Chopin (1810–1849) wrote almost exclusively for the piano and his nocturnes, etudes, mazurkas and waltzes are no less popular now than when he wrote them. This bust is a recent plaster version of a bronze bust that's in London's Guildhall, the site of Chopin's last concert in 1848.

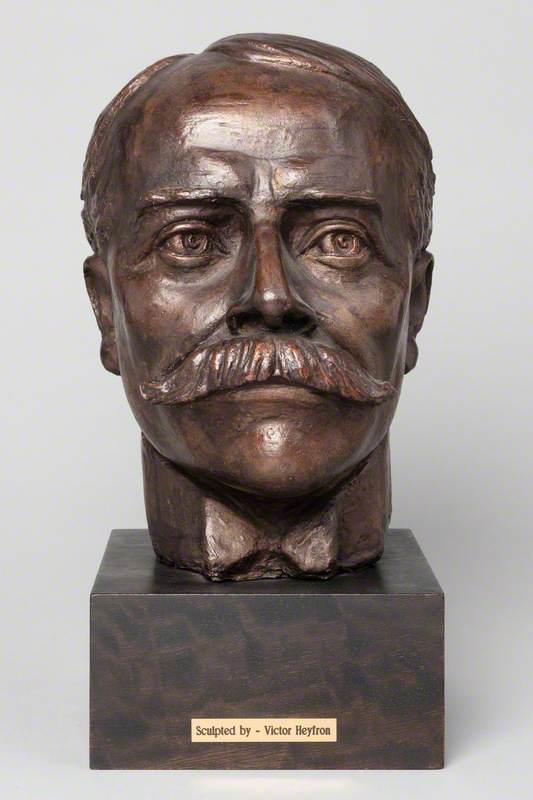

Franz Liszt (1811–1886) was a virtuoso pianist and composer born in Hungary. His piano compositions were often designed to show off his own skill in performance. This portrait bust of the composer in old age was modelled by the sculptor Joseph Edgar Boehm when Liszt visited London in 1886, the year he died.

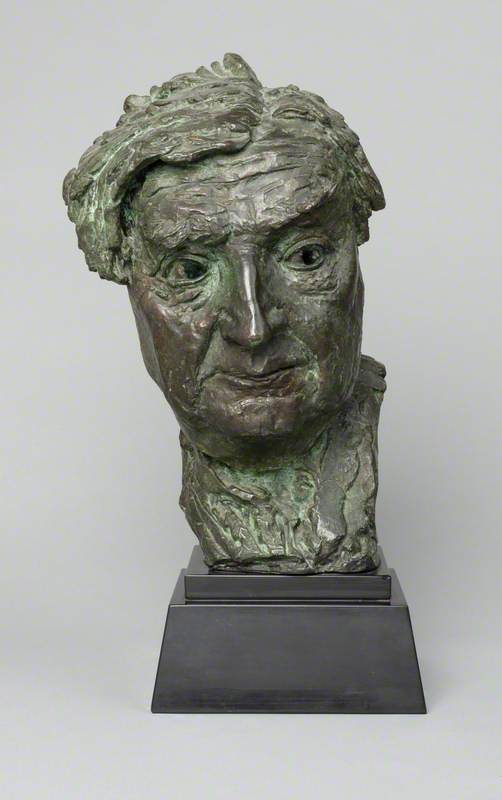

Richard Wagner (1813–1883) is one of the greatest figures in nineteenth-century classical music, but also one of the most controversial. He was lauded by many key figures from the world of music and beyond, but his prodigious writings on many topics included a virulent anti-semitic streak and, later on, he was Hitler's favourite composer.

These uncomfortable facts aside, his operas (or music-dramas) are full of majesty and bombast. They include Parsifal, Lohengrin, Tristan und Isolde and Tannhäuser. The Ring Cycle – actually four operas telling an overarching story of Teutonic myth (Das Rheingold, Die Walküre, Siegfried, Götterdämmerung) – is possibly the most ambitious piece of music theatre ever written.

Twentieth-century Brits

The move from the late Romantic era into the twentieth century is where music history starts to get very messy. Interesting, but messy! As in visual art, genres exploded all over the place, giving rise to atonality, serialism, neoclassicism, and much more.

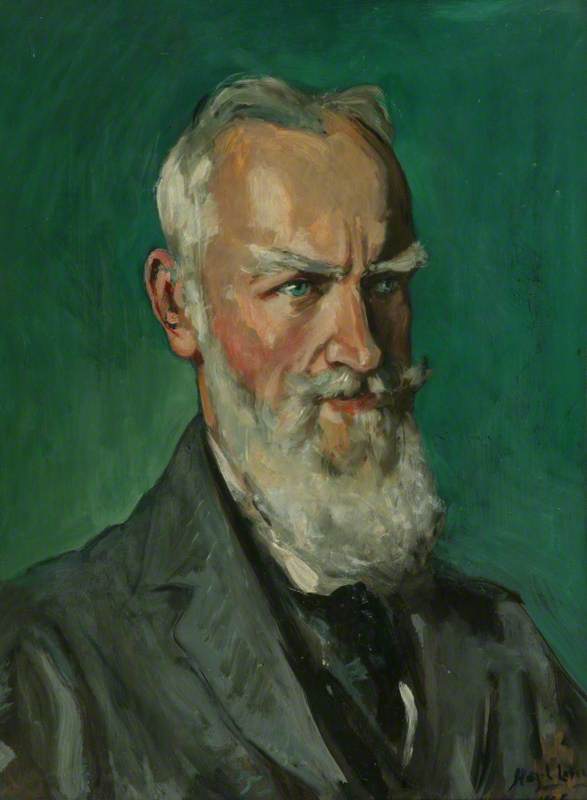

It also saw British composers such as Edward Elgar, Ralph Vaughan Williams and Benjamin Britten take their music to the world stage.

However, the busts of these later composers seem stylistically at odds with many of the earlier figures. The earlier ones often try to recreate the busts of the ancient classical world, while the twentieth-century visual art world broke away from these conventions and looked in new directions.

Where next?

Perhaps we shouldn't be too harsh on the original commissioners of these sculptures – they were, of course, products of their time, and therefore women composers are largely missing.

But equally, there's no Berlioz or Brahms. No Debussy or Rachmaninov. No Stravinsky or Shostakovich. No Mahler or Schoenberg. The changing fashions of music history have left us with an interesting group of artworks that give a particular view of what was considered 'good music'.

As I promised, here is the lone woman in our list – it's Dame Ethel Smyth (1858–1944) in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery.

Dame Ethel Mary Smyth (1858–1944)

1938

Gilbert William Bayes (1872–1953)

So why did Smyth have a bust made while others did not? One reason is that as well as being a composer of note, she was an important figure in the women's suffrage movement, writing the battle hymn 'The March of the Women'. However, her important suffrage work should not overshadow her achievements as a composer – she wrote operas, oratorios and concertos, and had to fight against the constraints of her gender and class to study composition.

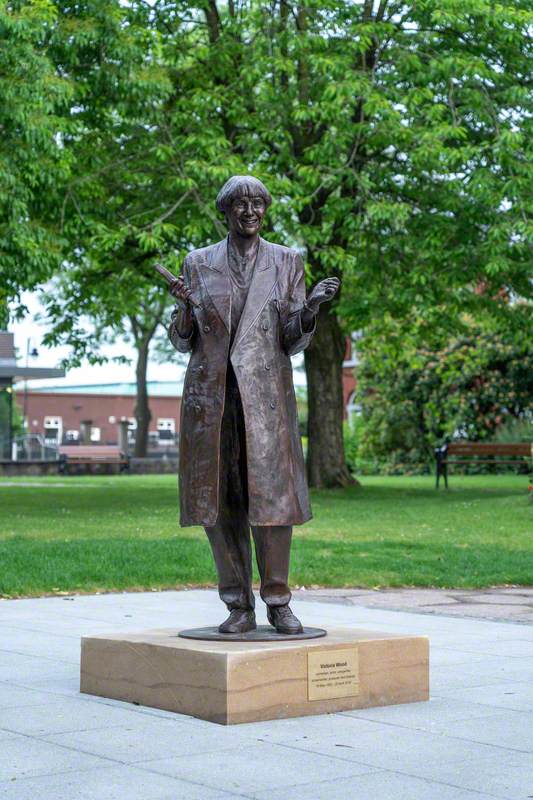

As an antidote to this historical sexism writ large, and as a coda to this piece, here's A MASSIVE LIST OF FEMALE COMPOSERS for you to enjoy! It's certainly worth hoping that – as with the recent commemoration of Suffragettes in stone – some of these composers will be immortalised in the not-too-distant future.

Andrew Shore, Head of Content at Art UK