Despite Scottish independence being at the forefront of contemporary political debate, it is difficult to imagine what an independent Scotland would look like. Present Scottish visual identity evolved from close partnership with England. It is well-documented that the nation capitalised on 'Highlandism' and bolstered this image to appear different to its southern neighbour. Since the Victorian era, people roamed Scotland's beautiful landscape to escape.

There is not much dissimilarity between Edwin Landseer's nineteenth-century landscape paintings and parts of Visit Scotland's recent 'Scotland is Calling' tourism advert.

Despite centuries dividing them, both convey a picturesque and mysterious place. As we approach the tenth anniversary of the 2014 independence referendum, it is interesting to explore the visual culture of Scotland before the 1707 Act of Union which united Scotland governmentally with England. Scotland depicted in the seventeenth century was wildly different in character to the Scotland seen in images today.

In 1603, Elizabeth I died unmarried and childless. The Crown passed to her cousin – James VI of Scotland (at this point he also became known as King James I of England). To commemorate this transition, numerous portraits of James VI and I were produced. A well-known James VI and I in the National Gallery of Scotland depicts a confident King wearing a pendant around his neck showing Saint George slaying the dragon.

Image credit: National Galleries of Scotland

John de Critz the elder (1551/1552–1642)

National Galleries of ScotlandHere, James was aligning himself with England's great hero to convey to his new English subjects that he was someone they could depend on. James has an ostentatious jewel on his hat, known as the Mirror of Great Britain. This ornament contains emblematic gems pertaining to events in English and Scottish history and, therefore, symbolises James' hopes for a glittering and strong Union under his reign. It seems the Union of Crowns started strong.

James left Scotland in April 1603 and promised to return tri-annually. However, between 1603 and 1624, he returned just once in 1617. Therefore, the visual culture evolving in seventeenth-century Scotland initially did so under an absent King.

Within this setting, Scotland's first home-produced portrait painter, George Jamesone, began painting the country's academics, merchants and nobility. Jamesone's Self Portrait hangs in the gallery of his hometown, Aberdeen.

In this, the artist sports a fashionable wide-brimmed hat, cloak and ruff. His appearance is evocative of a more famous artist – Rubens – particularly in his self-portrait in the Royal Collection, of which there are several copies on Art UK.

Looking to the above copy, there are some interesting comparisons between it and Jamesone's work. Notably, Rubens has his hands concealed under his cloak, whereas Jamesone has one of his on display. Jamesone has his paint palette propped up on a table beside him, whereas Rubens has nothing revealing his profession. Jamesone is inside, whereas Rubens is located outside.

Considering these differences, and noting Jamesone holds a small portrait, it is clear Rubens sees himself as nobility more so than Jamesone – who, by contrast, is quite content to straddle an identity between artisan and noble. By holding a small portrait, and proudly showing his paints, Jamesone acknowledges that he is where he is because of painting – he does not want to hide it.

This mentality of being happily self-made, and able to enter the strata of European nobility, is something that permeates seventeenth-century Scottish visual culture.

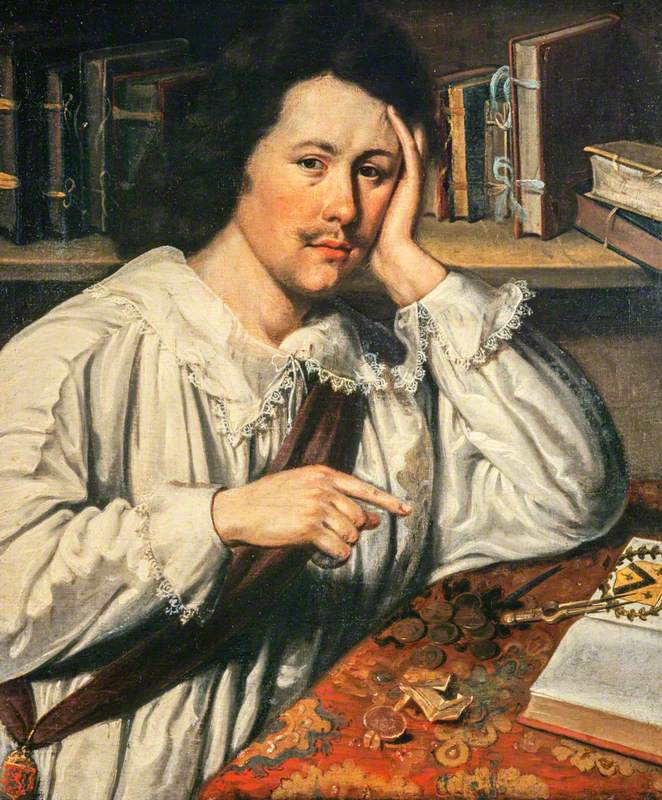

Image credit: National Galleries of Scotland

Sir James Balfour (1600–1657), Historian and Lord Lyon King-of-Arms after 1630

unknown artist

National Galleries of ScotlandA portrait of historian Sir James Balfour also conveys a feeling of contributing to the construction of a great European country. With his hand propping up his head, coupled with his positively bored demeanour, Balfour does not appear enthralled by his profession.

It's worth noting that this pose representing melancholy was popular in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century European art, as seen in Jan Davidsz. de Heem's picture below.

Image credit: Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Interior of a Room with a young Man seated at a Table 1628

Jan Davidsz de Heem (1606–1683/1684)

Ashmolean Museum, OxfordBy adopting it, Balfour conveys that he is a stylish European guy. It seems Balfour was basically saying that writing the Annals of the History of Scotland was no major concern to someone of his abilities.

Depicted with a drawing tool, coins and a collection of books, Balfour, like Jamesone, demonstrates that he can navigate a space between artisan and nobility because of his profession. He is proud to be personally engaged in boosting Scotland's prominence, and himself, via his work.

Anne, Countess of Rothes, with her Daughters (1626) by Jamesone is regarded as an important work for the insight it provides into seventeenth-century Scottish interiors.

Image credit: National Galleries of Scotland

George Jamesone (1589/1590–1644)

National Galleries of ScotlandThere is something strange about it though – note the paintings crammed together on the rear wall. This layout is not simply because Jamesone had trouble painting space, but because Anne was conveying something. Her message is revealed by the cherries cradled by one of her daughters. Cherries symbolised fertility in contemporary Dutch painting. It was popular to have your child depicted holding cherries to demonstrate how enduring (and fruitful) your lineage was.

Image credit: National Trust Images

Two Little Dutch Children in Aprons, Holding Apples, Cherries and a Straw Bag 1629

Dutch School

National Trust, Treasurer's House, YorkSo, cherries, combined with family portraits surrounding a seductive image of 'Venus Disarming Mars' demonstrate that Anne views herself, and her bloodline, as being of great importance. When this was commissioned, Anne's husband, the 6th Earl of Rothes, was in London petitioning against the Act of Revocation – the Crown's bid to revoke church or royal property in the hands of laymen. Considered altogether, this painting depicts a Scottish woman essentially telling the King to not mess with her dynasty.

Conveying meaning through symbolically placing images within images was a typically Dutch motif. It is something that Jamesone replicated in his later Self Portrait (c.1642).

Image credit: National Galleries of Scotland

George Jamesone (1589/1590–1644), Portrait Painter, Self Portrait c.1642

George Jamesone (1589/1590–1644)

National Galleries of ScotlandHere, the artist depicts himself in his studio. On the wall are portraits he has painted over his lifetime surrounding a scene depicting 'The Chastisement of Cupid'. Combined with the skull and hourglass on the table, symbolising vanitas, this curious scene suggests that Jamesone has had to reign in whimsy and desire in order to produce a body of work that will outlive himself and his sitters.

In addition to placing images within images to convey meaning, it was also common in seventeenth-century Scotland to carefully consider the actual location of such images within space for the purpose of optimising impact. The most well-documented instance of this would be the imagery used in the pageant that greeted Charles I when he visited Edinburgh in 1633.

One series illustrating the importance of location on a smaller scale, however, is Jamesone's series 'The Sybils', which depicts ancient Greek prophetesses and which the Principal of the University of Aberdeen placed in the University's Common Hall in 1641.

Amidst a turbulent religious landscape, with the rise of the Scottish Covenanters at odds with Charles I because of his Catholicism, marked by the Scottish National Covenant of 1638, these secular oracles who foretold Christianity reminded those inside the Common Hall of what united them spiritually, no matter what faction of Christianity they aligned with.

Although the art created in Scotland at this time was not as masterful as that of the Northern European region being emulated, the thought that went into where Scots placed images was incredibly intellectual. This practice demonstrates a level of visual intelligence that pre-empts the Enlightenment era that followed in the eighteenth century.

The visual culture of the Low Countries provided Scots with a language that they could use to create meaningful messages via art. This visual vocabulary was accessible via prints sourced directly from there. For example, Jamesone's 'Sibyls' were inspired by Dutch printmaker Crispijn de Passe the elder's engravings from 1601, XII Sibyllarum Icones Elegantissima.

Image credit: The Trustees of the British Museum

Sibylla Libyca, from the series 'The Sibyls'

1601, engraving on paper by Crispijn de Passe the elder (1564–1637)

Jamesone's Self Portrait explored earlier was likely based on Paulus Pontius' engraving after the original Rubens, as Jamesone would have been able to refer to it more easily in his studio.

Image credit: The Trustees of the British Museum

Anne of Denmark

c.1600–1652, engraving on paper by Claes Jansz. Visscher (1587–1652)

Similarly, Anne Countess of Rothes was based on Claes Jansz. Visscher's portrait of Anne of Denmark – no doubt selected to add additional charged meaning to an already fiery message. This transfer of images is indebted to Scotland's strong trading links with the area. At that time, it was easier for most Scots to get to Amsterdam by boat than it was to get to London by horse.

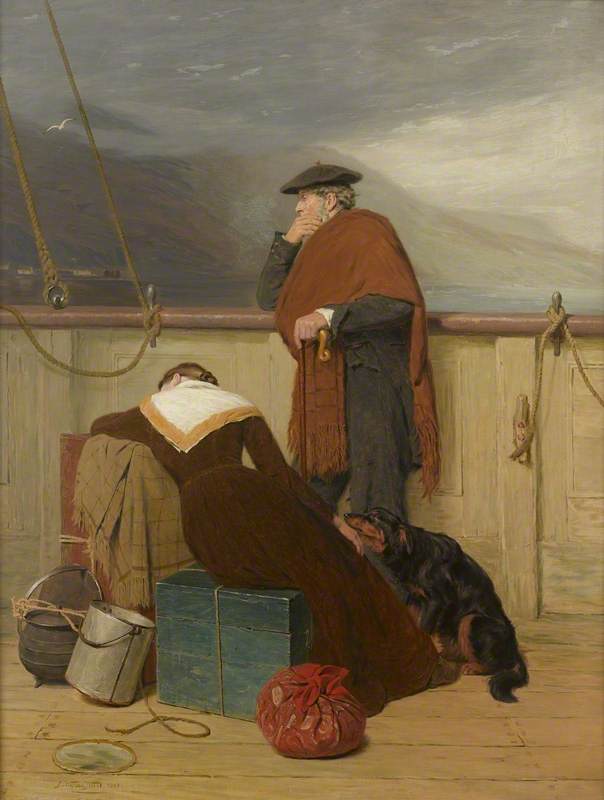

All of the seventeenth-century works explored in this story so far, bar one, are portraits. Although Jamesone's Sibyls are not portraits, they still depict figures. As suggested earlier, Scotland's identity went on to be articulated predominantly through landscape. The major difference between Scottish art before the Union, and that in the nineteenth century and beyond, is that the main subject of the former depicted people – people who shaped the aspirations and direction of the country.

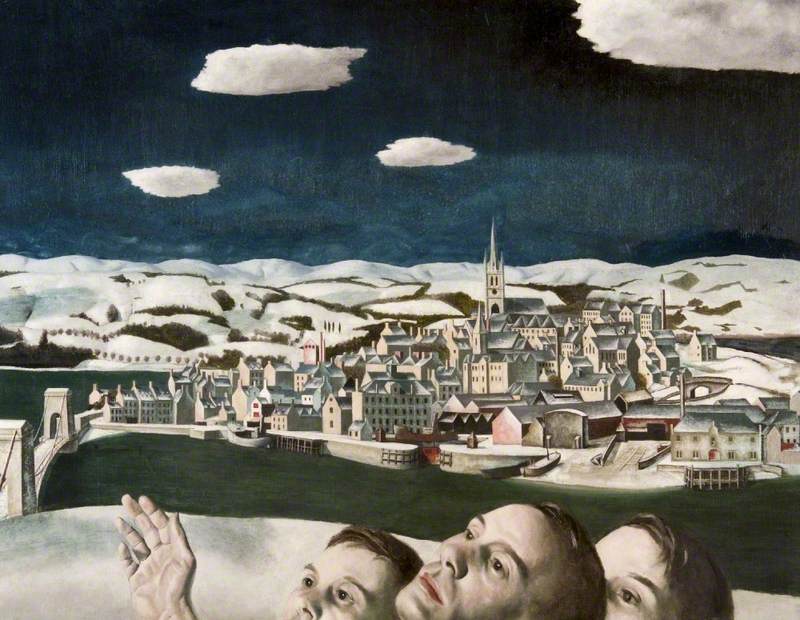

When we do catch a glimpse of place, the focus is usually architectural and, in the case of the above image of King's College, Aberdeen, further emphasises Scots' aspirations to be regarded as a successful and intellectually advanced Northern European society.

This image of Aberdeen, with scholars and townspeople getting on with their business at the foot of the University, bathed in golden light, is reminiscent of scenes by contemporary painters such as the follower of Barent Petersz. Avercamp, below, who captures the sophistication of Dutch society at this time.

Image credit: National Trust for Scotland, Hill of Tarvit Mansionhouse & Garden

Winter Landscape with Skaters on a River near a Town c.1620–1630

Barent Petersz. Avercamp (1612/1613–1679) (follower of)

National Trust for Scotland, Hill of Tarvit Mansionhouse & GardenSeventeenth-century Scottish art tells the story of independent people determined to be successful Europeans. Scots particularly admired the Dutch and their achievements and aspired to be like them. The images selected in this story capture a glimpse of how Scots felt about sharing a monarch with England, but with absent Kings and religious differences, they were not interested in uniting further.

It was the Scots' fierce ambition, captured vibrantly in a rare depiction of a Scottish warship, that eventually led to the 1707 Act of Union. With economic disaster stemming from the failed Darien scheme, combined with a devastating famine in the 1690s, Scotland needed help. When England delivered a lifeline via the Union, what it meant to be Scottish, and Scottish art, changed radically.

Fern Insh, art historian and arts engagement specialist

This content was funded by the Samuel H. Kress Foundation

Further reading

Svetlana Alpers, The Art of Describing, Chicago University Press, 1984

David McCrone, Scotland – The Brand: The Making of Scottish Heritage, Edinburgh University Press, 1995

John Morrison, Painting the Nation: Identity and Nationalism in Scottish Painting, 1800–1920, Edinburgh University Press, 2003

Jane Rickard, 'Stuart Coronations in Seventeenth-Century Scotland: History, Appropriation, and the Shaping of Cultural Identity', in Paulina Kewes and Andrew McRae (eds.), Stuart Succession Literature: Moments and Transformations, Oxford University Press, 2008

Roy Strong, 'Three Royal Jewels: The Three Brothers, the Mirror of Great Britain and the Feather', The Burlington Magazine, vol. 108, no. 760, 1966

University of Aberdeen, '18th century "glow up" of paintings provides insights into changing beauty standards', 7 March 2024