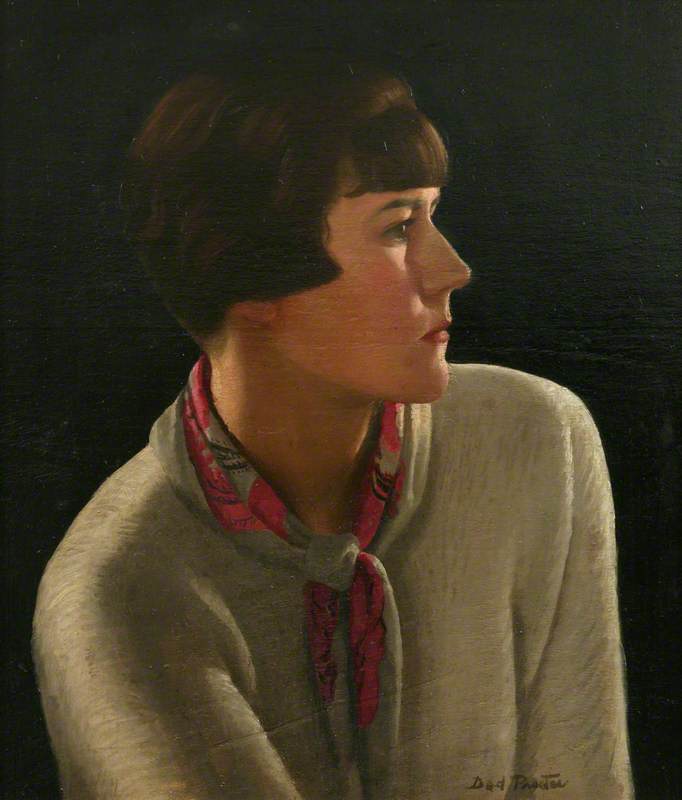

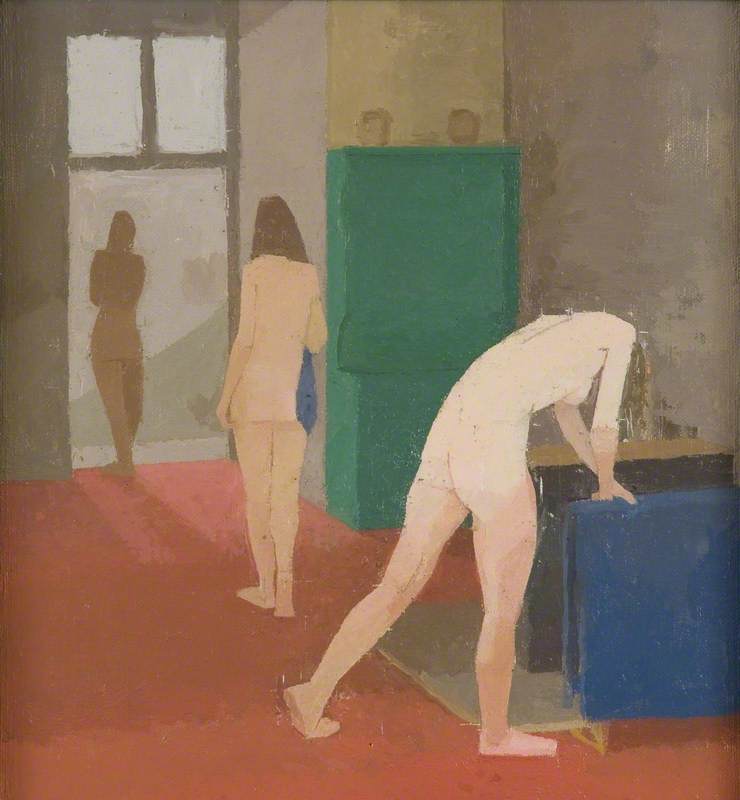

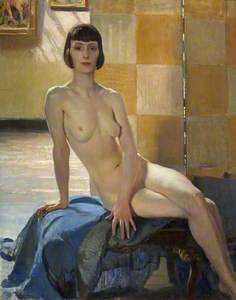

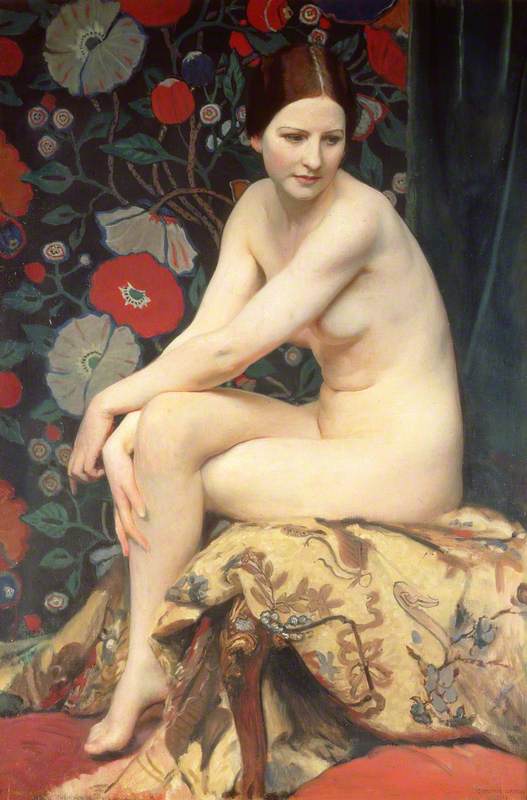

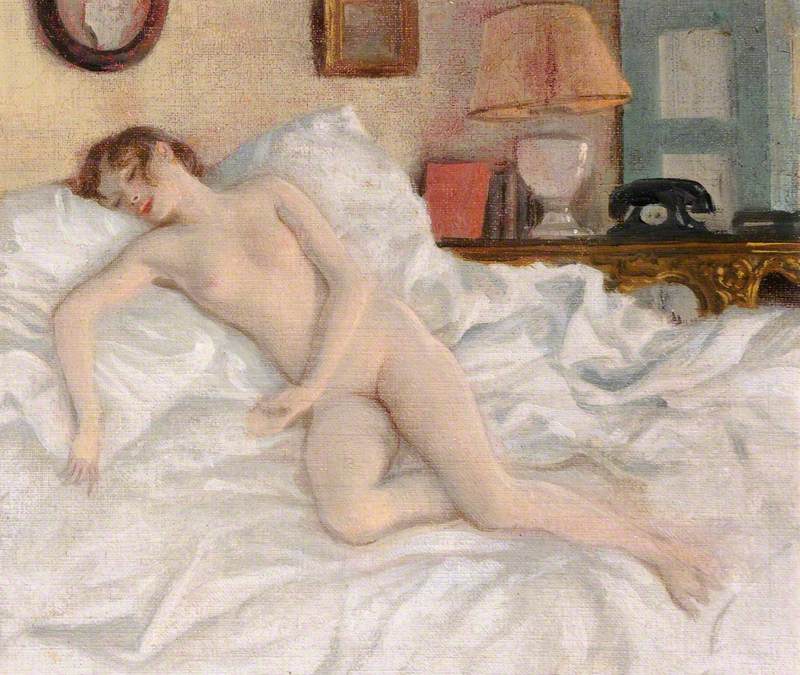

Trawling through Art UK, I came across this 1927 work by the artist George Spencer Watson.

It was the first painting in the collection of The Harris in Preston to feature a naked woman. As such, it was controversial, and some Councillors thought it would corrupt the morals of Prestonians.

History has not recorded any specific debauchery or low moral behaviour in Preston as a result of this artwork's display.

Watson's works in UK collections are a strange mix of sombre portraits and sensuous nudes, and sure enough, another of his nudes is now in Bournemouth, in the collection of the Russell-Cotes Art Gallery & Museum.

There is no specific reaction recorded to this particular painting, but it set me wondering if this had been a common occurrence in galleries throughout the land.

Surely the Preston nude can't be the only one that caused some controversy at the time... Well indeed not. Artistic nudes have had a complicated history, tied up with the male gaze, the public perception of what was 'decent' at different times in history, religion, and plenty of other factors.

There are famous examples that caused a stir in public such as Manet's Olympia and the 1917 exhibition of Modigliani's works that was closed, supposedly due to the depiction of pubic hair. There are private works not originally intended to be shown to the public, such as Goya's La Maya desnuda (The Naked Maja) and Courbet's L'Origine du monde (The Origin of the World) – both are now in major museums (the Prado and Musee D'Orsay respectively). But here's a quick look at some of the other works in the UK that have a salacious or saucy history.

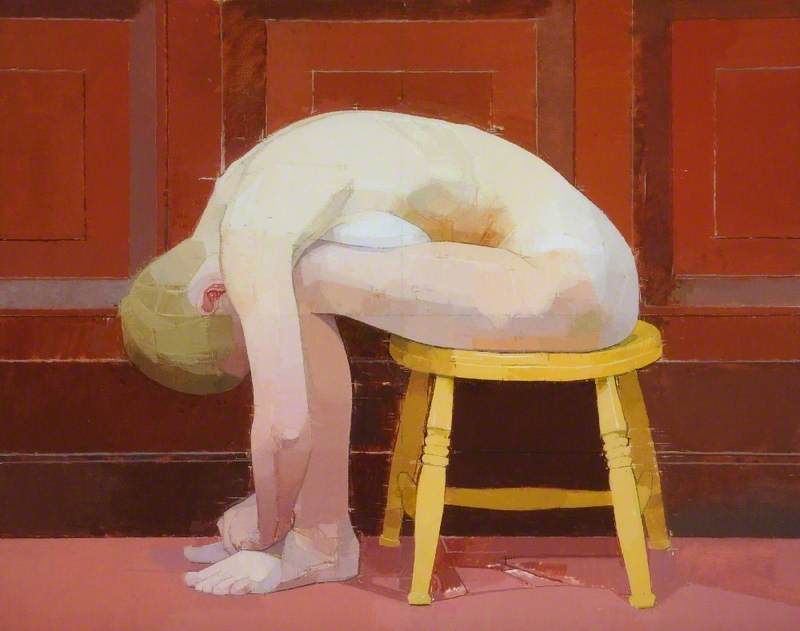

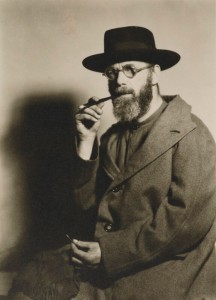

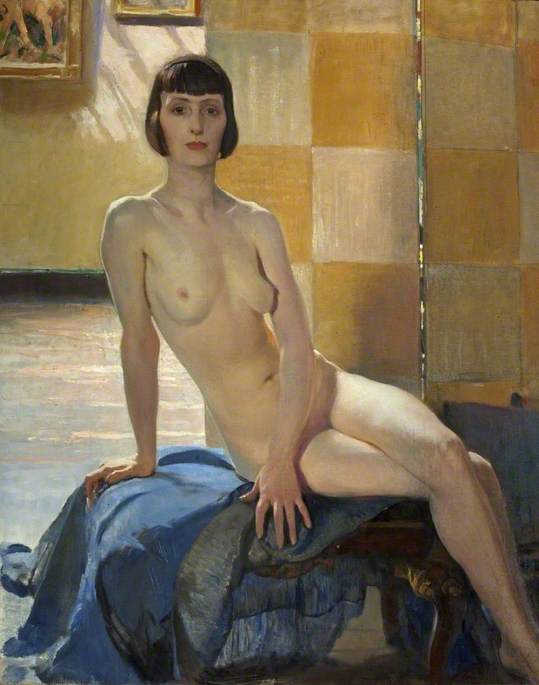

The next nude on our list is by the firmly establishment figure of Sir Gerald Festus Kelly. Kelly was one of the foremost portrait artists of his time, and yet even his standing could not prevent a public backlash when this painting went on display in Newport Museum and Art Gallery in 1947.

D. D. V (a); Nude Study; The Little Model; Petite modèle Anglaise

Gerald Festus Kelly (1879–1972)

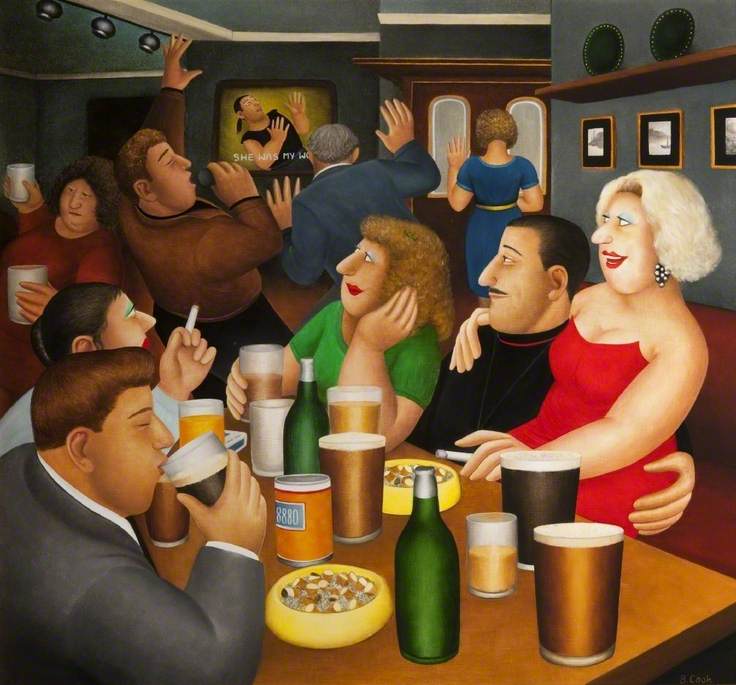

To be fair to the denizens of 1940s Newport, the fuss seems to have been caused mainly by one man, Dorian Herbert, who was the bishop of Caerleon for a small independent group called the Ancient British Church. His sister had seen some girls sniggering at the work, so he (naturally) went to see the picture for himself. Clearly it left quite an impression as he subsequently described it as 'brazen, abandoned and vulgar'. This didn't stop 20,000 people queuing up to see it (perhaps it even helped), or Kelly later becoming the President of the Royal Academy.

When it was put on display in the gallery again in 2008 the biggest complaint this time was that the model was smoking. How times change...

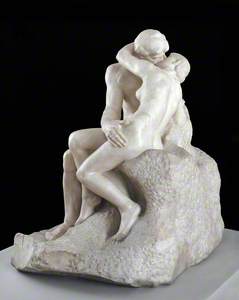

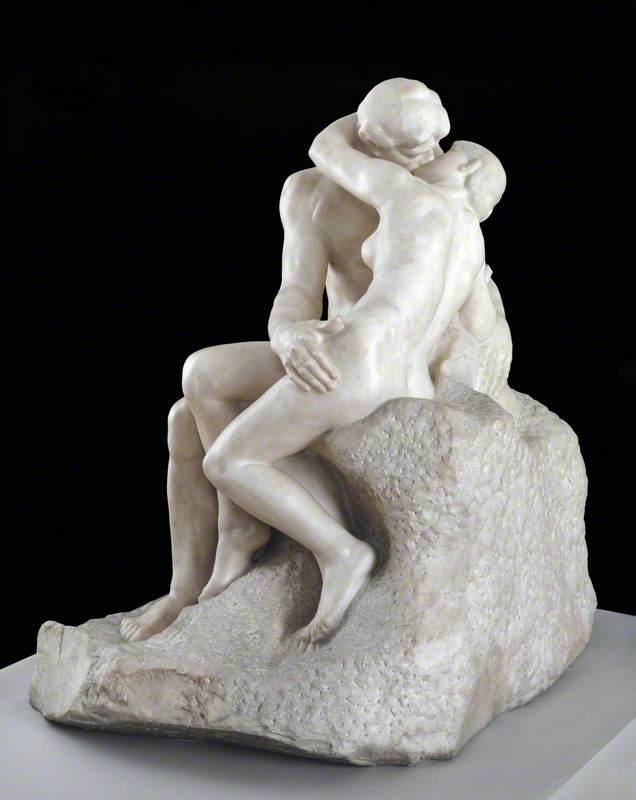

Going back a little further, in 1914 a version of Auguste Rodin's The Kiss was lent to Lewes Town Council for display in the Town Hall.

Originally conceived as just one part of the sculptor's large Gates of Hell, the embracing lovers are supposed to be Paolo and Francesca, who were real people but immortalised as a lustful couple in Dante's Divine Comedy.

Although the French public had embraced the work, the East Sussex town was perhaps not ready for the amorous subject matter. Soldiers were soon billeted in the Town Hall due to the start of the First World War, which led to this most famous of sculptures being draped in a tarpaulin. It was eventually acquired by the Tate in the 1950s and remains a firm favourite today.

You can find out more about its surprising history in this Tate Shots video.

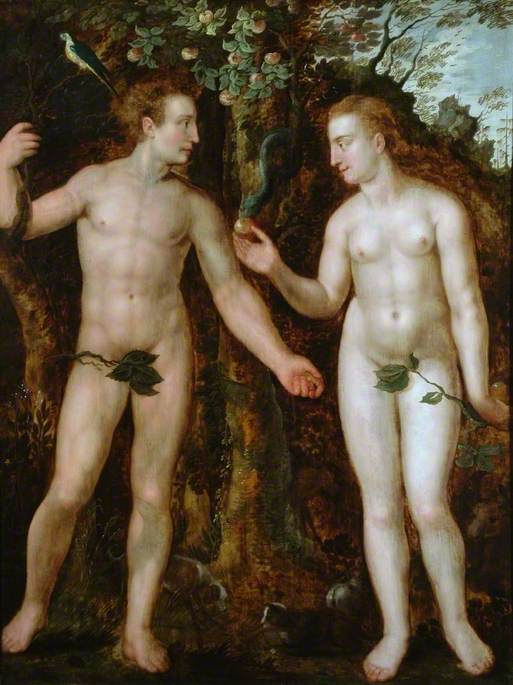

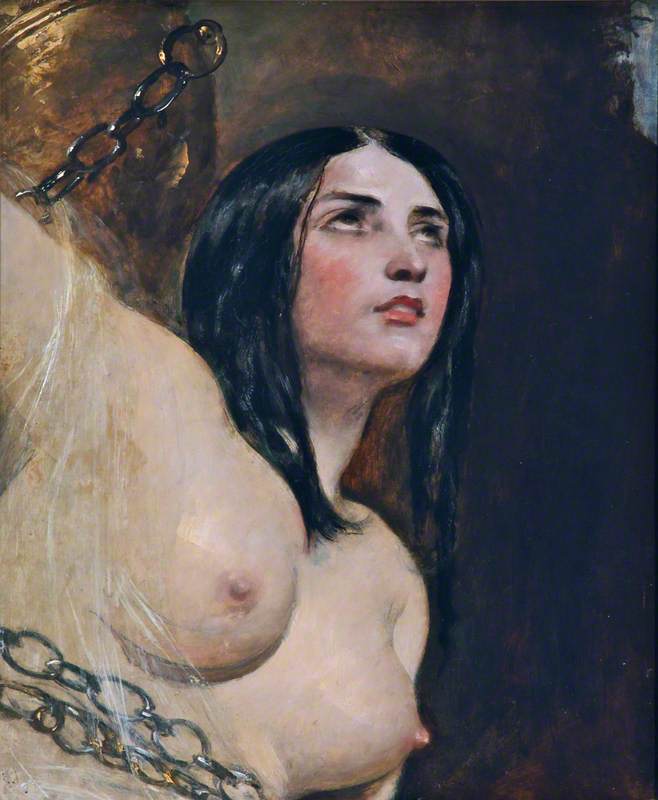

Some of the issues around depicting female nudes are that nudity was traditionally fine for representing goddesses, personifications or other mythological beings, but not for actual real women.

This can be shown in the works of Philip Wilson Steer – for example, his Seated Nude: The Black Hat, painted around 1900.

Steer was another establishment figure. He taught at the Slade from 1893 to 1930 and in 1931 was awarded the Order of Merit. The objections to this work were that the hat is modern, and therefore the viewer sees the model as a contemporary, real woman – not Eve, not Venus, not 'Spring'.

This oil sketch was not exhibited until it was chosen for the Tate Gallery by the Director John Rothenstein directly from Steer's studio in 1941. Steer said: 'friends told me it was spoiled by the hat; they thought it indecent that a nude should be wearing a hat, so it's never been shown.'

A similar composition of his is the coyly titled The Panama Hat, where the focus is once again not really on the hat.

Is it time for a nice cup of tea? Perhaps surprisingly for a portrait in a Scottish castle, this painting shows a lady drinking tea in the nude.

So far, so chilly. But why would this be considered scandalous? The reason is that it's thought that the model was the lady of the estate.

Close examination of the background, the red carpet and the lion skin, strongly indicates the Great Hall at Kinloch Castle as the location. From what we can see of the model's facial features, they are remarkably similar to photographs of Lady Bullough. The cup and saucer resemble pieces from a tea service in Lady Bullough's drawing room.

Posed away from the viewer, it's possible that this piece was always intended as a private piece for Sir George Bullough's eyes only (or indeed for one or more of her rumoured lovers). That's clearly no longer the case, but it's a beautiful painting – the only known work by Louis Galliac in a UK public collection.

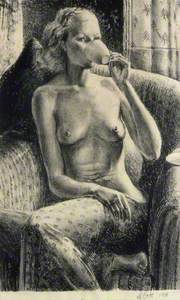

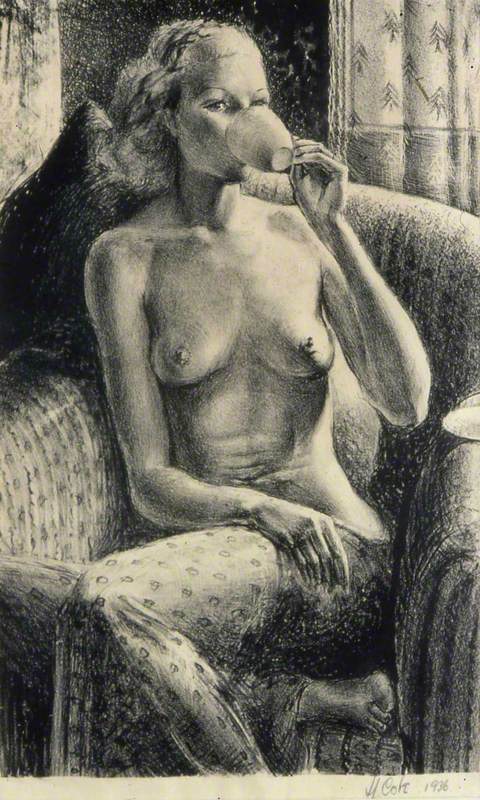

Drinking tea in the buff is apparently not uncommon, as shown by this lithograph by Leslie Cole of his wife Brenda.

Tea Drinking Nude

(the artist's wife, Brenda Cole, previously known as Barbara Harris) 1936

Leslie Cole (1910–1976)

Her portrait wasn't deemed scandalous, but you can read more about her extraordinary story in our article about her life.

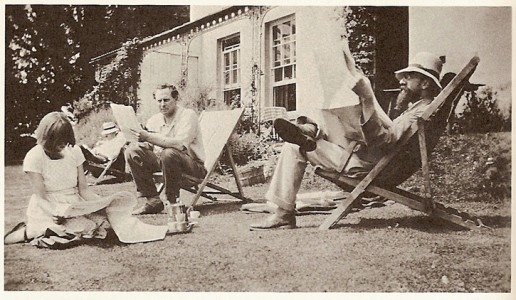

Back on the theme of artists painting the aristocratic ladies of the manor, it's worth looking at the case of Rex Whistler.

In 1936 Whistler was commissioned by Charles Paget (1885–1947), 6th Marquess of Anglesey to paint a trompe l'oeil for his country seat of Plas Newydd House in Wales. The finished work is an ambitious and fantastical mural, over 17.5 metres long – purportedly the largest work on canvas in the UK. Whistler undertook the commission on site, basically living with the Paget family for a couple of years while he progressed the work. During his stay he became infatuated with one of the Marquess' daughters, Lady Caroline Paget.

He painted her a number of times, including this nude.

It's not known if Lady Caroline posed for the work or if it's from Whistler's imagination. We do know that although the pair were friends, ultimately his love was unrequited, and he was to die in the Second World War, killed in action in Normandy. It seems unlikely the nude study was ever shown to the Marquess, and yet today it is on display in the National Trust property.

Artists sometimes use family members as their models, and here Ivor Williams unusually depicts a tender moment with perhaps unexpected nudity – his proposal to his wife.

This reclining nude was also modelled by the artist's wife.

But why the extra title? When the artist's daughter was a young girl the painting went on display, and a friend exclaimed 'Oh look it's Brown Owl!' Mrs Williams was Brown Owl of the local Brownies, and the young girl recognised her. There's probably not a badge for that.

So far, perhaps unsurprisingly, we've seen quite a few nude women, and it does seem to have been women's nudity in public galleries that people have found so objectionable. However, there are a couple of male nudes that also caused something of a stir.

In the late 1920s, the artist Eric Kennington was commissioned to create a sculpture for the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, intended to be situated above the School's Keppel Street entrance.

The Kennington Frieze

c.1928–1929

Eric Henri Kennington (1888–1960)

As you can see, the panel depicts a mother and child being protected from a fanged serpent by a nude, bearded, knife-wielding father. However, the trustees of the School did not appreciate the display of male genitalia and would not allow it to be placed above the School's entrance unless Kennington added a loincloth.

As one would hope from an artist with integrity, he refused to censor or change his vision and so the work was placed above the entrance of the library where it remains today. Perhaps some kind of brief would have been useful...

Male nudity in art had long been accepted as heroic and is found all the way back to ancient Greece. There are also works with clear homoerotic undertones in many male artists' works, from Michelangelo to Henry Scott Tuke.

However, having a woman artist creating a male nude has been something of a rarity, especially depicting any hint of genitalia. Student works by women on Art UK through the twentieth century show that even when they painted from life, the male models were often modestly covered.

That's perhaps why Sylvia Sleigh's works are sometimes seen as shocking – even today.

This full-frontal, unapologetically hairy, 1970s male is a sight not often seen in galleries. Certainly it wasn't four or five decades ago. The model, Paul Rosano, seems relaxed in his nakedness – he posed for Sleigh on several occasions. Sleigh's works are a forthright answer to the male gaze, subverting centuries of men looking at women.

Are these works shocking today? To the general public, probably not. Attitudes have largely changed, particularly in the past few decades. The breaking down of barriers around what is acceptable and what is shocking has possibly been hastened by the internet. The nude in art perhaps doesn't seem so provocative anymore, but can still be appreciated, and interrogated as a way into looking at social mores of the past.

Andrew Shore, Head of Content at Art UK

Get all the latest Art UK stories sent directly to your inbox when you sign up for our newsletter.

.jpg)